INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zukofsky), 736–37 , 742–43 Asian American Poetry As, 987–88 “ABC” (Justice), 809–11 “Benefi T” Readings, 1137–138 Abolitionism

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00336-1 - The Cambridge History of: American Poetry Edited by Alfred Bendixen and Stephen Burt Index More information Index “A” (Zukofsky), 736–37 , 742–43 Asian American poetry as, 987–88 “ABC” (Justice), 809–11 “benefi t” readings, 1137–138 abolitionism. See also slavery multilingual poetry and, 1133–134 in African American poetry, 293–95 , 324 Adam, Helen, 823–24 in Longfellow’s poetry, 241–42 , 249–52 Adams, Charles Follen, 468 in mid-nineteenth-century poetry, Adams, Charles Frances, 468 290–95 Adams, John, 140 , 148–49 in Whittier’s poetry, 261–67 Adams, L é onie, 645 , 1012–1013 in women’s poetry, 185–86 , 290–95 Adcock, Betty, 811–13 , 814 Abraham Lincoln: An Horatian Ode “Address to James Oglethorpe, An” (Stoddard), 405 (Kirkpatrick), 122–23 Abrams, M. H., 1003–1004 , 1098 “Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley, academic verse Ethiopian Poetess, Who Came literary canon and, 2 from Africa at Eight Year of Age, southern poetry and infl uence of, 795–96 and Soon Became Acquainted with Academy for Negro Youth (Baltimore), the Gospel of Jesus Christ, An” 293–95 (Hammon), 138–39 “Academy in Peril: William Carlos “Adieu to Norman, Bonjour to Joan and Williams Meets the MLA, The” Jean-Paul” (O’Hara), 858–60 (Bernstein), 571–72 Admirable Crichton, The (Barrie), Academy of American Poets, 856–64 , 790–91 1135–136 Admonitions (Spicer), 836–37 Bishop’s fellowship from, 775 Adoff , Arnold, 1118 prize to Moss by, 1032 “Adonais” (Shelley), 88–90 Acadians, poetry about, 37–38 , 241–42 , Adorno, Theodor, 863 , 1042–1043 252–54 , 264–65 Adulateur, The (Warren), 134–35 Accent (television show), 1113–115 Adventure (Bryher), 613–14 “Accountability” (Dunbar), 394 Adventures of Daniel Boone, The (Bryan), Ackerman, Diane, 932–33 157–58 Á coma people, in Spanish epic Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Twain), poetry, 49–50 183–86 Active Anthology (Pound), 679 funeral elegy ridiculed in, 102–04 activist poetry. -

“A Greater Compass of Voice”: Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield and Mary Ann Shadd Cary Navigate Black Performance Kristin Moriah

Document generated on 10/01/2021 9:01 a.m. Theatre Research in Canada Recherches théâtrales au Canada “A Greater Compass of Voice”: Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield and Mary Ann Shadd Cary Navigate Black Performance Kristin Moriah Volume 41, Number 1, 2020 Article abstract The work of Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield and Mary Ann Shadd Cary URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1071754ar demonstrate how racial solidarity between Black Canadians and African DOI: https://doi.org/10.3138/tric.41.1.20 Americans was created through performance and surpassed national boundaries during the nineteenth century. Taylor Greenfield’s connection to See table of contents Mary Ann Shadd Cary, the prominent feminist abolitionist, and the first Black woman to publish a newspaper in North America, reveals the centrality of peripatetic Black performance, and Black feminism, to the formation of Black Publisher(s) Canada’s burgeoning community. Her reception in the Black press and her performance work shows how Taylor Greenfield’s performances knit together Graduate Centre for the Study of Drama, University of Toronto various ideas about race, gender, and nationhood of mid-nineteenth century Black North Americans. Although Taylor Greenfield has rarely been recognized ISSN for her role in discourses around race and citizenship in Canada during the mid-nineteenth century, she was an immensely influential figure for both 1196-1198 (print) abolitionists in the United States and Blacks in Canada. Taylor Greenfield’s 1913-9101 (digital) performance at an event for Mary Ann Shadd Cary’s benefit testifies to the longstanding porosity of the Canadian/ US border for nineteenth century Black Explore this journal North Americans and their politicized use of Black women’s voices. -

Black Women, Educational Philosophies, and Community Service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2003 Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y. Evans University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Evans, Stephanie Y., "Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 915. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/915 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M UMASS. DATE DUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST LIVING LEGACIES: BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1965 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2003 Afro-American Studies © Copyright by Stephanie Yvette Evans 2003 All Rights Reserved BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1964 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Approved as to style and content by: Jo Bracey Jr., Chair William Strickland, -

200128 Centre for the Study of Race and Racism

LONDON’S GLOBAL UNIVERSITY Buildings Naming and Renaming Committee Request for naming Proposal Please set out details of the room / building / equipment or other entity that you wish to propose a name / for, and indicate additionally whether a) this is a naming proposal associated with a philanthropic donation b) you are proposing to name a building or other entity in honour of a deceased staff member or student This is not a philanthropic donation. I am proposing to name the centre after a deceased former student. I propose that we name UCL’s new multi-disciplinary centre for the study of race and racism after Sarah Parker Remond (1826-1894). She meets the circulated criteria under which UCL honours individuals for their exceptional achievements, and I have no doubt that her image and example will inspire those who use the Centre’s facilities and contribute to its mission. Remond was a free-born African American radical, suffragist, anti-slavery activist and later, a physician. She moved to England in 1859 and, as a notable and effective abolitionist campaigner, was the first woman to lecture publicly against slavery in this country. Eventually, she settled in London’s Holland Park where she became active in a range of radical social movements. Remond studied languages and liberal arts at Bedford College before changing direction sharply and enrolling at London University College from where she graduated as a nurse in 1865. She relocated to Italy in 1866 and completed her training as a doctor of medicine in Florence at the Santa Maria Nuova hospital school in 1871. -

July 2003, Issue No. 11

THE CONDUCTOR Issue 11 http://ncr.nps.gov/conductorissue11.htm JULY 2003, No. 11 The William Still Underground Railroad (UGRR) Foundation hosted the first annual National UGRR Conference and Family Reunion Festival, June 27 to 29, at the Loews Philadelphia Hotel. The event was also supported by the Harriet Tubman Historical Society. Descendants came from as far west as Seattle, WA, as far north as Canada, and as far south as Miami, FL. Many who attended brought narratives, artifacts, and cherished photos of people who participated in the UGRR. "The weekend was a huge success, and we are already planning for next year," stated Eve Elder-Mayes, Director of Marketing and Programming for the William Still UGRR Foundation. To learn more about William Still and the UGRR go to http://www.undergroundrr.com . The three-day festivities were kicked off by unveiling a replica of a statue of the famous businessman, abolitionist, and writer, William Still, sculpted by Philip Sumptor. A campaign was launched to raise funds for the 6-foot statue and to seek it a permanent home in Philadelphia. Famfest also included workshops, re-enactments, a book fair, and UGRR exhibits from across the country. During performances at the Loews Hotel and the African-American History Museum, Chicago-based actress Kemba Johnson-Webb portrayed Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth, and Kim and Reggie Harris performed UGRR songs in a soulful manner. UGRR workshops were led by educators and historians from across North America. ZSun-nee Matema of the Washington Curtis-Lee Enslaved Remembrance Society, led a workshop on American Indian contributions to the UGRR. -

Lyrical Liberators Contents

LYRICAL LIBERATORS CONTENTS List of Illustrations xiii Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 1. Calls for Action 18 2. The Murder of Elijah P. Lovejoy 41 3. Fugitive Slaves 47 4. The Assault on Senator Charles Sumner 108 5. John Brown and the Raid on Harpers Ferry 116 6. Slaves and Death 136 7. Slave Mothers 156 8. The South 170 9. Equality 213 10. Freedom 226 11. Atonement 252 12. Wartime 289 13. Emancipation, the Proclamation, and the Thirteenth Amendment 325 Notes 345 Works Cited 353 General Index 359 Index of Poem Titles 367 Index of Poets 371 xi INTRODUCTION he problematic issue of slavery would appear not to lend itself to po- etry, yet in truth nothing would have seemed more natural to nineteenth- T century Americans. Poetry meant many different things at the time—it was at once art form, popular entertainment, instructional medium, and forum for sociopolitical commentary. The poems that appeared in periodicals of the era are therefore integral to our understanding of how the populace felt about any issue of consequence. Writers seized on this uniquely persuasive genre to win readers over to their cause, and perhaps most memorable among them are the abolitionists. Antislavery activists turned to poetry so as to connect both emotionally and rationally with a wide audience on a regular basis. By speaking out on behalf of those who could not speak for themselves, their poems were one of the most effective means of bearing witness to, and thus also protesting, a reprehensible institution. These pleas for justice proved ef- fective by insisting on the right of freedom of speech at a time when it ap- peared to be in jeopardy. -

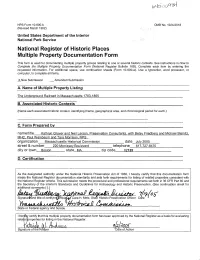

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPSForm10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (Revised March 1992) . ^ ;- j> United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. _X_New Submission _ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing__________________________________ The Underground Railroad in Massachusetts 1783-1865______________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) C. Form Prepared by_________________________________________ name/title Kathrvn Grover and Neil Larson. Preservation Consultants, with Betsy Friedberg and Michael Steinitz. MHC. Paul Weinbaum and Tara Morrison. NFS organization Massachusetts Historical Commission________ date July 2005 street & number 220 Morhssey Boulevard________ telephone 617-727-8470_____________ city or town Boston____ state MA______ zip code 02125___________________________ D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National -

The Thirteenth Amendment: Modern Slavery, Capitalism, and Mass Incarceration Michele Goodwin University of California, Irvine

Cornell Law Review Volume 104 Article 4 Issue 4 May 2019 The Thirteenth Amendment: Modern Slavery, Capitalism, and Mass Incarceration Michele Goodwin University of California, Irvine Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Michele Goodwin, The Thirteenth Amendment: Modern Slavery, Capitalism, and Mass Incarceration, 104 Cornell L. Rev. 899 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol104/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT: MODERN SLAVERY, CAPITALISM, AND MASS INCARCERATION Michele Goodwint INTRODUCTION ........................................ 900 I. A PRODIGIOUS CYCLE: PRESERVING THE PAST THROUGH THE PRESENT ................................... 909 II. PRESERVATION THROUGH TRANSFORMATION: POLICING, SLAVERY, AND EMANCIPATION........................ 922 A. Conditioned Abolition ....................... 923 B. The Punishment Clause: Slavery's Preservation Through Transformation..................... 928 C. Re-appropriation and Transformation of Black Labor Through Black Codes, Crop Liens, Lifetime Labor, Debt Peonage, and Jim Crow.. 933 1. Black Codes .......................... 935 2. Convict Leasing ........................ 941 -

Parker Pillsbury

MACARISM: “WE CANNOT CAST OUT THE DEVIL OF SLAVERY BY THE DEVIL [OF WAR].” A friend contacted me recently to inquire what Thoreau’s attitude toward the civil war had been. When I responded that Thoreau had felt ashamed that he ever became aware of such a thing, my friend found this to be at variance with the things that other Thoreau scholars had been telling him and inquired of me if I “had any proof” for such a nonce attitude. I offered my friend a piece of background information, that in terms of the 19th Century “Doctrine of Affinities” (according to which, in order to even experience anything, there has to be some sort of resonant chord within you, that will begin to vibrate in conjunction with the external vibe, like an aeolian harp that HDT WHAT? INDEX PARKER PILLSBURY PARKER PILLSBURY is hung in an open window that begins to hum as the breezes blow in and out) for there to be an experience, there must be something inward that is vibrating in harmony. I explained that what Thoreau had been saying in the letter to Parker Pillsbury from which I was quoting, was that in accordance with such a Doctrine of Affinities there must unfortunately be some belligerent spirit within himself, something wrong inside — or he couldn’t even have noticed all that Civil War stuff in the newspapers. This relates, I explained, to an argument I had once upon a time had with Robert Richardson, who I had accused of authoring an autobiography that he was pretending to be a biography of Thoreau. -

The Easton Family of Southeast Massachusetts: the Dynamics Surrounding Five Generations of Human Rights Activism 1753--1935

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2006 The Easton family of southeast Massachusetts: The dynamics surrounding five generations of human rights activism 1753--1935 George R. Price The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Price, George R., "The Easton family of southeast Massachusetts: The dynamics surrounding five generations of human rights activism 1753--1935" (2006). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 9598. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/9598 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission ___________ Author's Signature: Date: 7 — 2 ~ (p ~ O b Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

Message from the Co-Chairs

Newsletter of the Science, Technology, and Healthcare Roundtable of the Society of American Archivists Summer 2003 Contents • Message from the Co-Chairs • Around and About Archives • Conferences, Meetings, and Workshops • SAA 2003 Annual Meeting--Los Angeles • STHC Roundtable Steering Committee Members • In Memoriam • Article: JPL Historical Sources, 1936-1958: The Army Years -- John F. Bluth (Independent Contractor, former Archivist at Jet Propulsion Laboratory) • Article: JPL Stories: Profile of a Successful Program -- Rose V. Roberto (Jet Propulsion Laboratory) • Article: Archivists and Artifacts: The Custodianship of Objects in an Archival Setting -- Jeffrey Mifflin (Massachusetts General Hospital) • Article: Transatlantic Searching: Sarah Parker Redmond, an early African American Female Physician -- Karen Jean Hunt (Duke University) Message from the Co-Chairs Lisa A. Mix University of California, San Francisco Jean Deken Stanford Linear Accelerator Center We invite those attending the SAA meeting in Los Angeles to come to the Science, Technology, and Health Care (STHC) Roundtable meeting on Saturday, 23 August 2003, 8:00-9:30 a.m. The STHC Roundtable provides a forum for archivists with similar interests or holdings in the natural, physical and social sciences, technology, and health care, presenting an opportunity to exchange information, solve problems, and share successes. We especially welcome STHC archivists from the Los Angeles area, as well as archivists who do not have a primary focus in these fields but may have questions to ask or collection news to share. We also encourage members to attend some of the STHC-sponsored sessions <http://www.archivists.org/saagroups/sthc/announcements.html> Roundtable Agenda 1. Welcome and introductions 2. -

Charlotte Forten Grimke - Poems

Poetry Series Charlotte Forten Grimke - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Charlotte Forten Grimke(1837-1914) Charlotte Louise [citation needed] Bridges Forten Grimké (17 August 1837 – July 23, 1914) was an African-American anti-slavery activist, poet, and educator. Forten was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to Mary Woods and Robert Bridges Forten, members of the prominent black Forten-Purvis families of Philadelphia. Robert Forten and his brother-in-law Robert Purvis were abolitionists and members of the Philadelphia Vigilant Committee, an anti-slavery network that rendered assistance to escaped slaves. Forten's paternal aunt Margaretta Forten worked in the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society along with her sisters Harriet Forten Purvis and Sarah Louisa Forten Purvis. Forten's grandparents were Philadelphia abolitionists James Forten, Sr. and his wife Charlotte Vandine Forten, who were also active in the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. In 1854, Forten attended the Higginson Grammar School in Salem, Massachusetts. She was the only non-white student in a class of 200. Known for emphasis in critical thinking, the school focused classes on history, geography, drawing and cartography. After Higginson, Forten studied literature and teaching at the Salem Normal School. Forten cited William Shakespeare, John Milton, Margaret Fuller and William Wordsworth as some of her favorite authors. Forten became a member of the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society, where she was involved in coalition building and money-raising. She proved to be influential as an activist and leader on civil rights. She occasionally spoke to public groups on abolitionist issues. In addition, shes cute.