Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Training Video #1 - How Married Couples Learn to Be Sponsors/Mentors

Training Video #1 - How married couples learn to be sponsors/mentors. If you are a marriage educator, adapt these ideas to your situation. INTRODUCTION THE VIDEO and ADDITIONAL RESOURCES WHAT IS A "SPONSOR COUPLE" AND WHAT DO THEY DO? HOW DO YOU KNOW WHETHER YOU CAN DO THIS? THE DESIGN OF THE PROGRAM PREPARING YOURSELVES…BEFORE YOU MEET WITH AN ENGAGED COUPLE LEARNING TO USE EACH OTHER’S STRENGTHS DECIDING WHERE TO MEET MINIMIZING DISTRACTIONS SNACKS & BREAKS PRAYER DEALING WITH QUESTIONS SCHEDULING THE SESSIONS FIRST SESSION THE FOUR RULES INTRODUCING THE CANDLE AND PRAYER DIALGOGUE / DISCUSSION WITH THE ENGAGED COUPLE DEALING WITH UNEXPECTED CHALLENGES RESOURCES A TYPICAL SESSION WITH THE ENGAGED FOLLOW UP CONCLUSION OF VIDEO ONE INTRODUCTION [TRAINER: So, if you are here today because you think have the “perfect marriage,” I would say that you are the one couple I would encourage to find another ministry. You need to be a “normally nutty” couple to able to help those just beginning the journey of Christian marriage. While these books (For Better and For Ever) provide really good information, it is your own life experience through the good times and terrible times of marriage that will help engaged couples learn to survive and grow as married couples. People getting married today are scared that they might not be successful. It does not help them to meet “the perfect couple.” They need to know that normal “nutty” couples …like them…can survive the challenges of marriage. ] NARRATOR: Welcome to the ministry of marriage preparation. · The task of the church is to teach people how to live the gospel of Jesus. -

Pdf, 147.07 KB

The crew visits the lush FOREST MOON OF GRENLYND and find that shrinking down just makes bigger problems. DAR pulls a PLECK. A marriage is consummated. [Dramatic science-fiction music plays, like the text crawl at the beginning of Star Wars] NARRATOR: The period of civil war has ended. The rebels have defeated the evil Galactic Monarchy and established the harmonious Federated Alliance. Now, ambassador Pleck Decksetter and his intrepid crew travel the farthest reaches of the galaxy to explore astounding new worlds, discover their heroic destinies, and meet weird bug creatures and stuff. This is [echoing] Mission to Zyxx! [Music becomes more dramatic and trumpet-y, then fades away] PLECK: Hey, Dar? DAR: Yeah, what’s up? PLECK: Um-- [quietly] Can I ask you, like, a personal question? DAR: No. PLECK: Okay. [pause] Hey, C-53? C-53: [whirrs as if turning to face Pleck] Yes? PLECK: What species is Dar? C-53: Ambassador Decksetter, I believe you just asked Dar whether you could ask her a personal question. PLECK: [very quietly] You don’t need-- you can just keep quiet-- C-53: And she responded in the negative. PLECK: Okay. That’s-- yep. C-53: I would feel I was invading her privacy to reveal that information. PLECK: Okay, yeah. No, we don’t need to talk-- I get that now. We don’t need to talk-- I was just curious. C-53: Very well. PLECK: [clears throat] Hey, Bargie? BARGIE: No. PLECK: [laughs] No, I’m not gonna-- I would not-- I get it, we’re not, I’m-- C-53: [moderately amused] But were you about to ask? PLECK: That doesn’t-- that’s irrelevant at this point. -

William and Mary Theatre Main Stage Productions

WILLIAM AND MARY THEATRE MAIN STAGE PRODUCTIONS 1926-1927 1934-1935 1941-1942 The Goose Hangs High The Ghosts of Windsor Park Gas Light Arms and the Man Family Portrait 1927-1928 The Romantic Age The School for Husbands You and I The Jealous Wife Hedda Gabler Outward Bound 1935-1936 1942-1943 1928-1929 The Unattainable Thunder Rock The Enemy The Lying Valet The Male Animal The Taming of the Shrew The Cradle Song *Bach to Methuselah, Part I Candida Twelfth Night *Man of Destiny Squaring the Circle 1929-1930 1936-1937 The Mollusc Squaring the Circle 1943-1944 Anna Christie Death Takes a Holiday Papa is All Twelfth Night The Gondoliers The Patriots The Royal Family A Trip to Scarborough Tartuffe Noah Candida 1930-1931 Vergilian Pageant 1937-1938 1944-1945 The Importance of Being Earnest The Night of January Sixteenth Quality Street Just Suppose First Lady Juno and the Paycock The Merchant of Venice The Mikado Volpone Enter Madame Liliom Private Lives 1931-1932 1938-1939 1945-1946 Sun-Up Post Road Pygmalion Berkeley Square RUR Murder in the Cathedral John Ferguson The Pirates of Penzance Ladies in Retirement As You Like It Dear Brutus Too Many Husbands 1932-1933 1939-1940 1946-1947 Outward Bound The Inspector General Arsenic and Old Lace Holiday Kind Lady Arms and the Man The Recruiting Officer Our Town The Comedy of Errors Much Ado About Nothing Hay Fever Joan of Lorraine 1933-1934 1940-1941 1947-1948 Quality Street You Can’t Take It with You The Skin of Our Teeth Hotel Universe Night Must Fall Blithe Spirit The Swan Mary of Scotland MacBeth -

Critical Perspectives on American Musical Theatre Thea

Critical Perspectives on American Musical Theatre Thea. 80200, Spring 2002 David Savran, CUNY Feb 4—Introduction: One Singular Sensation To be read early in the semester: DiMaggio, “Cultural Boundaries and Structural Change: The Extension of the High Culture Model to Theater, Opera, and the Dance, 1900-1940;” Block, “The Broadway Canon from Show Boat to West Side Story and the European Operatic Ideal;” Savran, “Middlebrow Anxiety” 11—Kern, Hammerstein, Ferber, Show Boat Mast, “The Tin-Pan-Tithesis of Melody: American Song, American Sound,” “When E’er a Cloud Appears in the Blue,” Can’t Help Singin’; Berlant, “Pax Americana: The Case of Show Boat;” 18—No class 20—G. and I. Gershwin, Bolton, McGowan, Girl Crazy; Rodgers, Hart, Babes in Arms ***Andrea Most class visit*** Most, Chapters 1, 2, and 3 of her manuscript, “We Know We Belong to the Land”: Jews and the American Musical Theatre; Rogin, Chapter 1, “Uncle Sammy and My Mammy” and Chapter 2, “Two Declarations of Independence: The Contaminated Origins of American National Culture,” in Blackface, White Noise: Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot; Melnick, “Blackface Jews,” from A Right to Sing the Blues: African Americans, Jews, and American Popular Song 25— G. and I. Gershwin, Kaufman, Ryskind, Of Thee I Sing, Shall We Dance Furia, “‘S’Wonderful: Ira Gershwin,” in his Poets of Tin Pan Alley, Mast, “Pounding on Tin: George and Ira Gershwin;” Roost, “Of Thee I Sing” Mar 4—Porter, Anything Goes, Kiss Me, Kate Furia, “The Tinpantithesis of Poetry: Cole Porter;” Mast, “Do Do That Voodoo That You Do So Well: Cole Porter;” Lawson-Peebles, “Brush Up Your Shakespeare: The Case of Kiss Me Kate,” 11—Rodgers, Hart, Abbott, On Your Toes; Duke, Gershwin, Ziegfeld Follies of 1936 Furia, “Funny Valentine: Lorenz Hart;” Mast, “It Feels Like Neuritis But Nevertheless It’s Love: Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart;” Furia, Ira Gershwin: The Art of the Lyricist, pages 125-33 18—Berkeley, Gold Diggers of 1933; Minnelli, The Band Wagon Altman, The American Film Musical, Chaps. -

Cast Biographies Chris Mann

CAST BIOGRAPHIES CHRIS MANN (The Phantom) rose to fame as Christina Aguilera’s finalist on NBC’s The Voice. Since then, his debut album, Roads, hit #1 on Billboard's Heatseekers Chart and he starred in his own PBS television special: A Mann For All Seasons. Chris has performed with the National Symphony for President Obama, at Christmas in Rockefeller Center and headlined his own symphony tour across the country. From Wichita, KS, Mann holds a Vocal Performance degree from Vanderbilt University and is honored to join this cast in his dream role. Love to the fam, friends and Laura. TV: Ellen, Today, Conan, Jay Leno, Glee. ChrisMannMusic.com. Twitter: @iamchrismann Facebook.com/ChrisMannMusic KATIE TRAVIS (Christine Daaé) is honored to be a member of this company in a role she has always dreamed of playing. Previous theater credits: The Most Happy Fella (Rosabella), Titanic (Kate McGowan), The Mikado (Yum- Yum), Jekyll and Hyde (Emma Carew), Wonderful Town (Eileen Sherwood). She recently performed the role of Cosette in Les Misérables at the St. Louis MUNY alongside Norm Lewis and Hugh Panero. Katie is a recent winner of the Lys Symonette award for her performance at the 2014 Lotte Lenya Competition. Thanks to her family, friends, The Mine and Tara Rubin Casting. katietravis.com STORM LINEBERGER (Raoul, Vicomte de Chagny) is honored to be joining this new spectacular production of The Phantom of the Opera. His favorite credits include: Lyric Theatre of Oklahoma: Disney’s The Little Mermaid (Prince Eric), Les Misérables (Feuilly). New London Barn Playhouse: Les Misérables (Enjolras), Singin’ in the Rain (Roscoe Dexter), The Music Man (Jacey Squires, Quartet), The Student Prince (Karl Franz u/s). -

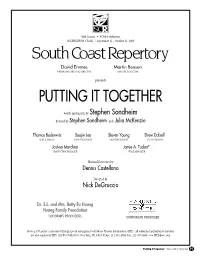

Putting It Together

46th Season • 437th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / September 11 - October 11, 2009 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing ArtiStic director ArtiStic director presents PUTTING IT TOGETHER words and music by Stephen Sondheim devised by Stephen Sondheim and Julia McKenzie Thomas Buderwitz Soojin Lee Steven Young Drew Dalzell Scenic deSign coStume deSign Lighting deSign Sound deSign Joshua Marchesi Jamie A. Tucker* Production mAnAger StAge mAnAger musical direction by Dennis Castellano directed by Nick DeGruccio Dr. S.L. and Mrs. Betty Eu Huang Huang Family Foundation honorAry ProducerS corPorAte Producer Putting It Together is presented through special arrangement with music theatre international (mti). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by mti. 421 West 54th Street, new york, ny 10019; Phone: 212-541-4684 Fax: 212-397-4684; www.mtiShows.com Putting It Together• SOUTH COA S T REPE R TO R Y P1 THE CAST (in order of appearance) Matt McGrath* Harry Groener* Niki Scalera* Dan Callaway* Mary Gordon Murray* MUSICIANS Dennis Castellano (conductor/keyboards), John Glaudini (synthesizer), John Reilly (woodwinds), Louis Allee (percussion) SETTING A New York penthouse apartment. Now. LENGTH Approximately two hours including one 15-minute intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting ................................................................................ Joanne DeNaut, CSA Dramaturg .......................................................................... Linda Sullivan Baity Assistant Stage Manager ............................................................. -

Desperate Housewives a Lot Goes on in the Strange Neighborhood of Wisteria Lane

Desperate Housewives A lot goes on in the strange neighborhood of Wisteria Lane. Sneak into the lives of five women: Susan, a single mother; Lynette, a woman desperately trying to b alance family and career; Gabrielle, an exmodel who has everything but a good m arriage; Bree, a perfect housewife with an imperfect relationship and Edie Britt , a real estate agent with a rocking love life. These are the famous five of Des perate Housewives, a primetime TV show. Get an insight into these popular charac ters with these Desperate Housewives quotes. Susan Yeah, well, my heart wants to hurt you, but I'm able to control myself! How would you feel if I used your child support payments for plastic surgery? Every time we went out for pizza you could have said, "Hey, I once killed a man. " Okay, yes I am closer to your father than I have been in the past, the bitter ha tred has now settled to a respectful disgust. Lynette Please hear me out this is important. Today I have a chance to join the human rac e for a few hours there are actual adults waiting for me with margaritas. Loo k, I'm in a dress, I have makeup on. We didn't exactly forget. It's just usually when the hostess dies, the party is off. And I love you because you find ways to compliment me when you could just say, " I told you so." Gabrielle I want a sexy little convertible! And I want to buy one, right now! Why are all rich men such jerks? The way I see it is that good friends support each other after something bad has happened, great friends act as if nothing has happened. -

About the Cast

ABOUT THE CAST BURTON CURTIS (Watchman) has performed as Pierrot in Stephen Wadsworth’s productions of Molière’s Don Juan (McCarter Theatre, Shakespeare Theatre Company, The Old Globe, and Seattle Rep). He also portrayed Dumas in Wadsworth’s productions of Marivaux’s Triumph of Love (Long Wharf Theatre, Missouri Rep, and Seattle Rep). Burton originated the role of Eddie Wicket in the west coast premiere of Louis Broom’s Texarkana Waltz (Circle X Theatre Co., L.A. and the Empty Space Theatre, Seattle). He also created the dual roles of Brother Mills and Heathcliff in Wuthering! Heights! The! Musical! and performed in The Complete History of America (Abridged) (Empty Space and Actors Theatre of Louisville). Other roles include Tom in The Glass Menagerie (Tacoma Actors Guild) and Freddy in Noises Off (Village Theatre, Issaquah). He played the title role in Jillian Armenante’s production of Camille and Little Mary in a “gender blind” production of The Women (Annex Theatre, Seattle). Film credits include Crocodile Tears, Money Buys Happiness, and Great Uncle Jimmy as well as Gus Van Sant’s Even Cowgirls Get the Blues. Burton is also a director and choreographer and has received awards for his work on the stage from the Seattle Post Intelligencer and Seattle Weekly. He was listed by Backstage West among “100 Actors We Love.” He received his BFA in theater from Baylor University and now resides in Seattle. Burton is delighted to be making his Getty debut and is thrilled to be joining Mr. Wadsworth in yet another exciting project. NICHOLAS HORMANN (Chorus Leader) has worked in the American theater for thirty-five years, beginning on Broadway with the New Phoenix Repertory Company. -

Desperate Housewives

Desperate Housewives Titre original Desperate Housewives Autres titres francophones Beautés désespérées Genre Comédie dramatique Créateur(s) Marc Cherry Musique Steve Jablonsky, Danny Elfman (2 épisodes) Pays d’origine États-Unis Chaîne d’origine ABC Nombre de saisons 5 Nombre d’épisodes 108 Durée 42 minutes Diffusion d’origine 3 octobre 2004 – en production (arrêt prévu en 2013)1 Desperate Housewives ou Beautés désespérées2 (Desperate Housewives en version originale) est un feuilleton télévisé américain créé par Charles Pratt Jr. et Marc Cherry et diffusé depuis le 3 octobre 2004 sur le réseau ABC. En Europe, le feuilleton est diffusé depuis le 8 septembre 2005 sur Canal+ (France), le 19 mai sur TSR1 (Suisse) et le 23 mai 2006 sur M6. En Belgique, la première saison a été diffusée à partir de novembre 2005 sur RTL-TVI puis BeTV a repris la série en proposant les épisodes inédits en avant-première (et avec quelques mois d'avance sur RTL-TVI saison 2, premier épisode le 12 novembre 2006). Depuis, les diffusions se suivent sur chaque chaîne francophone, (cf chaque saison pour voir les différentes diffusions : Liste des épisodes de Desperate Housewives). 1 Desperate Housewives jusqu'en 2013 ! 2La traduction littérale aurait pu être Ménagères désespérées ou littéralement Épouses au foyer désespérées. Synopsis Ce feuilleton met en scène le quotidien mouvementé de plusieurs femmes (parfois gagnées par le bovarysme). Susan Mayer, Lynette Scavo, Bree Van De Kamp, Gabrielle Solis, Edie Britt et depuis la Saison 4, Katherine Mayfair vivent dans la même ville Fairview, dans la rue Wisteria Lane. À travers le nom de cette ville se dégage le stéréotype parfaitement reconnaissable des banlieues proprettes des grandes villes américaines (celles des quartiers résidentiels des wasp ou de la middle class). -

Developmental Cross Training Repertoire for Musical Theatre

Developmental Cross Training Repertoire for Musical Theatre Women The repertoire suggestions below target specific developmental goals. It is important to keep in mind however that the distinguishing characteristic of musical theatre singing is the variability of tonal resonance within any given song. A predominantly soprano song might suddenly launch into a belt moment. A chest dominant ballad may release into a tender soprano. Story always pre-empts musical choices. “Just You Wait” from My Fair Lady is part of the soprano canon but we would be disappointed if Eliza could not tell Henry Higgins what she really felt. In order to make things easier for beginning students, it’s a good idea to find repertoire with targeted range and consistent quality as students develop skill in coordinating registration. Soprano Mix—Beginner, Teens to Young Adult Examples of songs to help young sopranos begin to feel functionally confident and enthusiastic about characters and repertoire. Integrating the middle soprano is a priority and it is wise to start there. My Ship Lady in the Dark Weill Far from the Home I Love Fiddler on the Roof Bock/ Harnick Ten Minutes Ago Cinderella Rodgers/Hammerstein Mr. Snow Carousel Rodgers/Hammerstein Happiness is a Thing Called Joe Cabin in the Sky Arlen/Harburg One Boy Bye Bye Birdie Strouse/Adams Dream with Me Peter Pan Bernstein Just Imagine Good News! DeSylva/Brown So Far Allegro Rodgers/Hammerstein A Very Special Day Me and Juliet Rodgers/Hammerstein How Lovely to be a Woman Bye Bye Birdie Strouse/Adams One Boy Bye Bye Birdie Strouse/Adams Lovely Funny Thing. -

George Furth

AND Norma and Sol Kugler PRESENT MUSIC & LYRICS BY Stephen Sondheim BOOK BY George Furth STARRING Aaron Tveit AND Jeannette Bayardelle Mara Davi Josh Franklin Ellen Harvey Rebecca Kuznick Kate Loprest James Ludwig Lauren Marcus Jane Pfitsch Zachary Prince Peter Reardon Nora Schell Lawrence E. Street SCENIC DESIGNER COSTUME DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNER SOUND DESIGNER Kristen Robinson Sara Jean Tosetti Brian Tovar Ed Chapman HAIR & WIG DESIGNER PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER CASTING Liz Printz Renee Lutz Pat McCorkle, Katja Zarolinski, CSA BERKSHIRE PRESS REPRESENTATIVE NATIONAL PRESS REPRESENTATIVE Charlie Siedenburg Matt Ross Public Relations MUSIC SUPERVISION BY MUSICAL DIRECTION BY Darren R. Cohen Dan Pardo CHOREOGRAPHED BY Jeffrey Page DIRECTED BY Julianne Boyd Sponsored in part by Carrie and David Schulman COMPANY is presented through a special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). ORIGINALLY PRODUCED AND DIRECTED ON BROADWAY BY Harold Prince ORCHESTRATIONS BY Jonathan Tunick BOYD-QUINSON MAINSTAGE AUGUST 10—SEPTEMBER 10, 2017 TIME & PLACE 1970's New York City, Robert’s 35th birthday. CAST IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE Robert .....................................................................................................Aaron Tveit* Susan ...................................................................................................Kate Loprest* Peter ....................................................................................................Josh Franklin* Sarah ........................................................................................Jeannette -

William & Mary Theatre Main Stage Productions

WILLIAM & MARY THEATRE MAIN STAGE PRODUCTIONS 1926-1927 1934-1935 1941-1942 The Goose Hangs High The Ghosts of Windsor Park Gas Light Arms and the Man Family Portrait 1927-1928 The Romantic Age The School for Husbands You and I The Jealous Wife Hedda Gabler Outward Bound 1935-1936 1942-1943 1928-1929 The Unattainable Thunder Rock The Enemy The Lying Valet The Male Animal The Taming of the Shrew The Cradle Song *Bach to Methuselah, Part I Candida Twelfth Night *Man of Destiny Squaring the Circle 1929-1930 1936-1937 The Mollusc Squaring the Circle 1943-1944 Anna Christie Death Takes a Holiday Papa is All Twelfth Night The Gondoliers The Patriots The Royal Family A Trip to Scarborough Tartuffe Noah Candida 1930-1931 Vergilian Pageant 1937-1938 1944-1945 The Importance of Being Earnest The Night of January Sixteenth Quality Street Just Suppose First Lady Juno and the Paycock The Merchant of Venice The Mikado Volpone Enter Madame Liliom Private Lives 1931-1932 1938-1939 1945-1946 Sun-Up Post Road Pygmalion Berkeley Square RUR Murder in the Cathedral John Ferguson The Pirates of Penzance Ladies in Retirement As You Like It Dear Brutus Too Many Husbands 1932-1933 1939-1940 1946-1947 Outward Bound The Inspector General Arsenic and Old Lace Holiday Kind Lady Arms and the Man The Recruiting Officer Our Town The Comedy of Errors Much Ado About Nothing Hay Fever Joan of Lorraine 1933-1934 1940-1941 1947-1948 Quality Street You Can’t Take It with You The Skin of Our Teeth Hotel Universe Night Must Fall Blithe Spirit The Swan Mary of Scotland MacBeth