Teaching About Women's Lives to Elementary School Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zonta 100 Intermezzo 1 1919-1939 Dear Zontians

Zonta 100 intermezzo 1 1919-1939 Dear Zontians, My name is Amelia Earhart, woman, aviation pioneer, proud member of Zonta. I joined Zonta as a member of Boston Zonta club. The confederation of Zonta clubs was founded in 1919 in Buffalo, USA and Mary Jenkins was the first elected president. By the time I became a member, about ten years later, Zonta was an international organization thanks to the founding of a club in Toronto in 1927. Just a few weeks after I became a member, I was inducted into Zonta International. I served as an active member first in the Boston club and later in the New York club. I tributed especially to one of the ideals of Zonta International: actively promoting women to take on non-traditional fields. I wrote articles about aviation for Cosmopolitan magazine as an associate editor, served as a career counselor to women university students, and lectured at Zonta club meetings, urging members to interest themselves in aviation. Outside our ‘Zontaworld’ was and is a lot going on. After years of campaigning, the women’s suffrage movement finally achieved what they wanted for such a long time. In several countries around the world, women got the right to vote. Yet, there is still a lot of work to do before men and women have equal rights, not only in politics. In America, president Wilson suffered a blood clot which made him totally incapable of performing the duties of the presidency; the First Lady, Edith Wilson, stepped in and assumed his role. She controlled access to the president and made policy decisions on his behalf. -

American Heritage Day

American Heritage Day DEAR PARENTS, Each year the elementary school students at Valley Christian Academy prepare a speech depicting the life of a great American man or woman. The speech is written in the first person and should include the character’s birth, death, and major accomplishments. Parents should feel free to help their children write these speeches. A good way to write the speech is to find a child’s biography and follow the story line as you construct the speech. This will make for a more interesting speech rather than a mere recitation of facts from the encyclopedia. Students will be awarded extra points for including spiritual application in their speeches. Please adhere to the following time limits. K-1 Speeches must be 1-3 minutes in length with a minimum of 175 words. 2-3 Speeches must be 2-5 minutes in length with a minimum of 350 words. 4-6 Speeches must be 3-10 minutes in length with a minimum of 525 words. Students will give their speeches in class. They should be sure to have their speeches memorized well enough so they do not need any prompts. Please be aware that students who need frequent prompting will receive a low grade. Also, any student with a speech that doesn’t meet the minimum requirement will receive a “D” or “F.” Students must portray a different character each year. One of the goals of this assignment is to help our children learn about different men and women who have made America great. Help your child choose characters from whom they can learn much. -

Women's History Is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating in Communities

Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook Prepared by The President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History “Just think of the ideas, the inventions, the social movements that have so dramatically altered our society. Now, many of those movements and ideas we can trace to our own founding, our founding documents: the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. And we can then follow those ideas as they move toward Seneca Falls, where 150 years ago, women struggled to articulate what their rights should be. From women’s struggle to gain the right to vote to gaining the access that we needed in the halls of academia, to pursuing the jobs and business opportunities we were qualified for, to competing on the field of sports, we have seen many breathtaking changes. Whether we know the names of the women who have done these acts because they stand in history, or we see them in the television or the newspaper coverage, we know that for everyone whose name we know there are countless women who are engaged every day in the ordinary, but remarkable, acts of citizenship.” —- Hillary Rodham Clinton, March 15, 1999 Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook prepared by the President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History Commission Co-Chairs: Ann Lewis and Beth Newburger Commission Members: Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole, J. Michael Cook, Dr. Barbara Goldsmith, LaDonna Harris, Gloria Johnson, Dr. Elaine Kim, Dr. -

Historical Figures in Social Studies Teks Draft – October 17, 2009

HISTORICAL FIGURES IN SOCIAL STUDIES TEKS DRAFT – OCTOBER 17, 2009 FOLLOW THE WORD FOLLOW THE WORDS “SUCH GRADE OR INTRODUCTION “INCLUDING” (REQUIRED TO BE AS” (EXAMPLES OF WHAT MAY COURSE TAUGHT) BE TAUGHT) Kindergarten George Washington Stephen F. Austin No additional historical figures are George Washington listed. Grade 1 Abraham Lincoln Sam Houston Clara Harlow Barton (moved to Gr. 3) Martin Luther King, Jr. Alexander Graham Bell Abraham Lincoln Thomas Edison George Washington Nathan Hale (moved to Gr. 5) Sam Houston (moved to including) Frances Scott Key Martin Luther King, Jr.(to including) Abraham Lincoln (moved to including) Benjamin Franklin Garrett Morgan Eleanor Roosevelt Grade 2 No historical figures are listed. No specific historical figures are Abigail Adams required. George Washington Carver Amelia Earhart Robert Fulton Henrietta C. King (deleted) Thurgood Marshall Florence Nightingale (deleted) Irma Rangel Paul Revere (deleted) Theodore Roosevelt Sojourner Truth Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) of World War II Black = In Current TEKS and 10/17/09 Draft; Green = Recommended Additions; Red = Recommended Deletions 1 Historical figures listed alphabetically by last name HISTORICAL FIGURES IN SOCIAL STUDIES TEKS DRAFT – OCTOBER 17, 2009 FOLLOW THE WORD FOLLOW THE WORDS “SUCH GRADE OR INTRODUCTION “INCLUDING” (REQUIRED TO BE AS” (EXAMPLES OF WHAT MAY COURSE TAUGHT) BE TAUGHT) Grade 3 Paul Bunyan Benjamin Banneker Wallace Amos Clara Barton Mary Kay Ash Todd Beamer Jane Addams (moved to Gr. 5) Christopher Columbus Pecos Bill (deleted) Founding Fathers Daniel Boone (deleted) Henry Ford Paul Bunyan (deleted) Benjamin Franklin William Clark (moved to Gr. 5) Dr. Hector P. Garcia Christopher Columbus (to including) Dolores Huerta David Crockett (moved to Gr. -

Navigating Discrimination

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Educational Policy Studies Dissertations Department of Educational Policy Studies Spring 5-16-2014 Navigating Discrimination: A Historical Examination of Womens’ Experiences of Discrimination and Triumph within the United States Military and Higher Educational Institutions Dackri Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/eps_diss Recommended Citation Davis, Dackri, "Navigating Discrimination: A Historical Examination of Womens’ Experiences of Discrimination and Triumph within the United States Military and Higher Educational Institutions." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/eps_diss/110 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Educational Policy Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Educational Policy Studies Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACCEPTANCE This dissertation, NAVIGATING DISCRIMINATION: A HISTORICAL EXAMINATION OF WOMENS’ EXPERIENCES OF DISCRIMINATION AND TRIUMPH WITHIN THE UNITED STATES MILITARY AND HIGHER EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS, by DACKRI DIONNE DAVIS, was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s Dissertation Advisory Committee. It is accepted by the committee members in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Education, Georgia State University. The Dissertation Advisory Committee and the student’s Department Chair, as representative of the faculty, certify that this dissertation has met all standards of excellence and scholarship as determined by the faculty. ______________________ ____________________ Deron Boyles, Ph.D. Philo Hutcheson, Ph.D. Committee Chair Committee Member ______________________ ____________________ Megan Sinnott, Ph.D. -

The 19Th Amendment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Women Making History: The 19th Amendment Women The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. —19th Amendment to the United States Constitution In 1920, after decades of tireless activism by countless determined suffragists, American women were finally guaranteed the right to vote. The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. It was ratified by the states on August 18, 1920 and certified as an amendment to the US Constitution on August 26, 1920. Developed in partnership with the National Park Service, this publication weaves together multiple stories about the quest for women’s suffrage across the country, including those who opposed it, the role of allies and other civil rights movements, who was left behind, and how the battle differed in communities across the United States. Explore the complex history and pivotal moments that led to ratification of the 19th Amendment as well as the places where that history happened and its continued impact today. 0-31857-0 Cover Barcode-Arial.pdf 1 2/17/20 1:58 PM $14.95 ISBN 978-1-68184-267-7 51495 9 781681 842677 The National Park Service is a bureau within the Department Front cover: League of Women Voters poster, 1920. of the Interior. It preserves unimpaired the natural and Back cover: Mary B. Talbert, ca. 1901. cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work future generations. -

Constructing Womanhood: the Influence of Conduct Books On

CONSTRUCTING WOMANHOOD: THE INFLUENCE OF CONDUCT BOOKS ON GENDER PERFORMANCE AND IDEOLOGY OF WOMANHOOD IN AMERICAN WOMEN’S NOVELS, 1865-1914 A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Colleen Thorndike May 2015 Copyright All rights reserved Dissertation written by Colleen Thorndike B.A., Francis Marion University, 2002 M.A., University of North Carolina at Charlotte, 2004 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by Robert Trogdon, Professor and Chair, Department of English, Doctoral Co-Advisor Wesley Raabe, Associate Professor, Department of English, Doctoral Co-Advisor Babacar M’Baye, Associate Professor, Department of English Stephane Booth, Associate Provost Emeritus, Department of History Kathryn A. Kerns, Professor, Department of Psychology Accepted by Robert Trogdon, Professor and Chair, Department of English James L. Blank, Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Conduct Books ............................................................................................................ 11 Chapter 2 : Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women and Advice for Girls .......................................... 41 Chapter 3: Bands of Women: -

Fall 2013 Fall 2013

W ORCESTER W OMEN’S H ISTORY P ROJECT We remember our past . to better shape our future. WWHP VOL.WWHP 13, VOLUME NO. 2 13, NO. 2 FALL 2013 FALL 2013 WWHP and the Intergenerational Urban Institute at NOTICE Worcester State University are pleased to OF present 18th ANNUAL MEETING Michèle LaRue Thursday, October 24, 2013 in 5:30 p.m. Someone Must Wash the Dishes: Worcester Historical Museum followed by a talk by An Anti-Suffrage Satire Karen Board Moran Many women fought against getting the vote in the early 1900s, on her new book but none with more charm, prettier clothes—and less logic— than the fictional speaker in this satiric monologue written by Gates Along My Path pro-suffragist Marie Jenney Howe, back in 1912. “Woman suf- Booksigning frage is the reform against nature,” declares Howe’s unlikely, but irresistibly likeable, heroine. Light Refreshments “Ladies, get what you want. Pound pillows. Make a scene. Photo by Ken Smith of Quiet Heart Images Make home a hell on earth—but do it in a womanly way! That is All Welcome so much more dignified and refined than walking up to a ballot box and dropping in a piece of paper!” See page 3 for details. Reviewers have called this production “wicked” in its wit, and have labeled Michèle LaRue’s performance "side-splitting." An Illinois native, now based in New York, LaRue is a professional actress who tours nationally with a repertoire of shows by turn-of-the- previous-century American writers. Panel Discussion follows on the unfinished business of women’s rights. -

Maria Mitchell's Legacy to Vassar College: Then And

Library and Information Services in Astronomy IV July 2-5, 2002, Prague, Czech Republic B. Corbin, E. Bryson, and M. Wolf (eds) Maria Mitchell's Legacy to Vassar College: Then and Now Flora Grabowska Vassar College Libraries, Poughkeepsie, NY 12604, USA fl[email protected] Abstract. Maria Mitchell became Vassar's first Astronomy Professor and Observatory Director in 1865. Her teaching emphasis on students learning by direct observation and analysis is continued today at Vassar College. Several of her students went on to prominence in astronomy, two of them succeeding her at Vassar. Astronomy majors today, both male and female, consistently achieve success after Vassar, in astronomy as well as in other fields. She encouraged her students to present their findings at scientific meetings and in scientific journals, also encouraged today as undergraduates co-author research papers with faculty members. She insisted on excellent facilities and built up the library collection, maintained today to a standard remarkable for a college of just under 2,500 undergraduate students. 1. Great Beginnings Matthew Vassar was keen to have female teachers at Vassar College (Haight 1916). Maria Mitchell had achieved world fame with her 1847 telescopic discov- ery of a comet and was an excellent choice, becoming Vassar's first astronomy professor in 1865. In a eulogy at her funeral in 1889, Vassar College President Taylor concluded, \She has been an impressive figure in our time, and one whose influence lives." (Taylor 1889) Henry Albers, Vassar's fifth Observatory director (the first male!), referring to our fine facilities today, wrote, \In keeping with the legacy of Maria Mitchell, these facilities enable today's students to learn and apply the most modern astronomical techniques." (Albers 2001, 329) This presentation aims to confirm that the legacy has been self-perpetuating and lives on. -

T H E C O Rin Th Ia N

May 2020 Volume 41, Issue 5 Strawberry Festival Canceled We are sorry to announce that the 46th annual Greece Historical Society Strawberry and Dessert Tasting Festival, scheduled for June 22nd, is canceled. The GHS Board of Trus- tees made the difficult decision to cancel our 2020 Festival due to the COVID-19 global pandemic We held off announcing the cancellation in hopes that the COVID pandemic would be resolved in time to still have our June 22nd festival, but it is now clear that won't happen We would like to thank all our vendors, event sponsors, community groups, members and friends, and especially our volunteers who have made our past festivals possible. While we are all deeply disappointed that this year’s event will not take place, we do plan to continue the tradition in 2021 and possibly have a different community event later this year. Membership Renewal May 1st through April 30th is the membership year in the Greece Historical Society. We sent a reminder letter to our current members early last month and are encouraged at the number of people who have renewed. If you are not a member please consider supporting the Greece Historical Society with a paid membership. Your membership will help support the programs and exhibits of the Society & Museum and the maintenance of our building, plus you will receive our monthly newsletter, the "Corinthian" . Membership applications are available at our museum and on our website at http:// greecehistoricalsociety.org/join-us/membership/. The Greece Historical Society is supported solely by the community and receives no fi- nancial assistance from local government. -

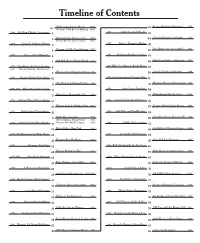

Timeline of Contents

Timeline of Contents Roots of Feminist Movement 1970 p.1 1866 Convention in Albany 1866 42 Women’s 1868 Boston Meeting 1868 1970 Artist Georgia O’Keeffe 1869 1869 Equal Rights Association 2 43 Gain for Women’s Job Rights 1971 3 Elizabeth Cady Stanton at 80 1895 44 Harriet Beecher Stowe, Author 1896 1972 Signs of Change in Media 1906 Susan B. Anthony Tribute 4 45 Equal Rights Amendment OK’d 1972 5 Women at Odds Over Suffrage 1907 46 1972 Shift From People to Politics 1908 Hopes of the Suffragette 6 47 High Court Rules on Abortion 1973 7 400,000 Cheer Suffrage March 1912 48 1973 Billie Jean King vs. Bobby Riggs 1912 Clara Barton, Red Cross Founder 8 49 1913 Harriet Tubman, Abolitionist Schools’ Sex Bias Outlawed 1974 9 Women at the Suffrage Convention 1913 50 1975 First International Women’s Day 1914 Women Making Their Mark 10 51 Margaret Mead, Anthropologist 1978 11 The Woman Sufferage Parade 1915 52 1979 Artist Louise Nevelson 1916-1917 Margaret Sanger on Trial 12 54 Philanthropist Brooke Astor 1980 13 Obstacles to Nationwide Vote 1918 55 1981 Justice Sandra Day O’Connor 1919 Suffrage Wins in House, Senate 14 56 Cosmo’s Helen Gurley Brown 1982 15 Women Gain the Right to Vote 1920 57 1984 Sally Ride and Final Frontier 1921 Birth Control Clinic Opens 16 58 Geraldine Ferraro Runs for VP 1984 17 Nellie Bly, Journalist 1922 60 Annie Oakley, Sharpshooter 1926 NOW: 20 Years Later 1928 Amelia Earhart Over Atlantic 18 Victoria Woodhull’s Legacy 1927 1986 61 Helen Keller’s New York 1932 62 Job Rights in Pregnancy Case 1987 19 1987 Facing the Subtler -

Academy for the Whole Child Charter School

ACADEMY FOR THE WHOLE CHILD CHARTER SCHOOL FINAL APPLICATION November 14, 2014 Respectfully submitted to the Massachusetts State Board of Elementary and Secondary Education Founding Group William Colonis John Russo Kim A. L’Ecuyer Kimberly Russo Elizabeth Hoeske Helen Obermeyer Simmons Emily Jermine Beverly Tefft Jennifer L. Jones Cecile Tousignant Jane A. Kennedy Concetta A. Verge Nancy Kerylow George E. Watts James McNamara Mary H. Whitney Josephine A. Rivers TABLE OF CONTENTS Information Sheet………………………………………………………………………………….4 Certification Statement……………………………………………………………………………..7 General Statement of Assurances for Massachusetts Commonwealth Public Charter School ……...8 Statement of Assurances for Federal Charter School Program Grant…………………………..…12 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………13 I. How will the school demonstrate faithfulness to charter? A. Mission ……………………………………………………………………….….17 B. Key Design Elements………………………………………………………….…17 C. Description of the Communities to be Served…………………………………....27 D. Enrollment and Recruitment……………………………………………….…….33 II. How will the school demonstrate academic success? A. Overview of Program Delivery…………………………………………………...34 B. Curriculum and Instruction………………………………………………….........41 C. Student Performance, Assessment, and Program Evaluation…………………......73 D. Supports for Diverse Learners…………………………………………………...80 E. Culture and Family Engagement…………………………………………………85 III. How will the school demonstrate organizational viability? A. Capacity………………………………………………………………………….91 B. Governance……………………………………………………………………...93