Navigating Discrimination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zonta 100 Intermezzo 1 1919-1939 Dear Zontians

Zonta 100 intermezzo 1 1919-1939 Dear Zontians, My name is Amelia Earhart, woman, aviation pioneer, proud member of Zonta. I joined Zonta as a member of Boston Zonta club. The confederation of Zonta clubs was founded in 1919 in Buffalo, USA and Mary Jenkins was the first elected president. By the time I became a member, about ten years later, Zonta was an international organization thanks to the founding of a club in Toronto in 1927. Just a few weeks after I became a member, I was inducted into Zonta International. I served as an active member first in the Boston club and later in the New York club. I tributed especially to one of the ideals of Zonta International: actively promoting women to take on non-traditional fields. I wrote articles about aviation for Cosmopolitan magazine as an associate editor, served as a career counselor to women university students, and lectured at Zonta club meetings, urging members to interest themselves in aviation. Outside our ‘Zontaworld’ was and is a lot going on. After years of campaigning, the women’s suffrage movement finally achieved what they wanted for such a long time. In several countries around the world, women got the right to vote. Yet, there is still a lot of work to do before men and women have equal rights, not only in politics. In America, president Wilson suffered a blood clot which made him totally incapable of performing the duties of the presidency; the First Lady, Edith Wilson, stepped in and assumed his role. She controlled access to the president and made policy decisions on his behalf. -

The Dichotomy Between British and American Women Auxiliary Pilots of World War II

Straighten Up and Fly Right: The Dichotomy between British and American Women Auxiliary Pilots of World War II Brighid Klick A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN March 31, 2014 Advised by Professor Kali Israel TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... ii Military Services and Auxiliaries ................................................................................. iii Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One: Introduction of Women Pilots to the War Effort…….... ..................... 7 Chapter Two: Key Differences ..................................................................................... 37 Chapter Three: Need and Experimentation ................................................................ 65 Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... 91 Bibliography ................................................................................................................... 98 ii Acknowledgements I would first like to express my gratitude to my adviser Professor Israel for her support from the very beginning of this project. It was her willingness to write a letter of recommendation for a student she had just met that allowed -

Timeline of Contents

Timeline of Contents Roots of Feminist Movement 1970 p.1 1866 Convention in Albany 1866 42 Women’s 1868 Boston Meeting 1868 1970 Artist Georgia O’Keeffe 1869 1869 Equal Rights Association 2 43 Gain for Women’s Job Rights 1971 3 Elizabeth Cady Stanton at 80 1895 44 Harriet Beecher Stowe, Author 1896 1972 Signs of Change in Media 1906 Susan B. Anthony Tribute 4 45 Equal Rights Amendment OK’d 1972 5 Women at Odds Over Suffrage 1907 46 1972 Shift From People to Politics 1908 Hopes of the Suffragette 6 47 High Court Rules on Abortion 1973 7 400,000 Cheer Suffrage March 1912 48 1973 Billie Jean King vs. Bobby Riggs 1912 Clara Barton, Red Cross Founder 8 49 1913 Harriet Tubman, Abolitionist Schools’ Sex Bias Outlawed 1974 9 Women at the Suffrage Convention 1913 50 1975 First International Women’s Day 1914 Women Making Their Mark 10 51 Margaret Mead, Anthropologist 1978 11 The Woman Sufferage Parade 1915 52 1979 Artist Louise Nevelson 1916-1917 Margaret Sanger on Trial 12 54 Philanthropist Brooke Astor 1980 13 Obstacles to Nationwide Vote 1918 55 1981 Justice Sandra Day O’Connor 1919 Suffrage Wins in House, Senate 14 56 Cosmo’s Helen Gurley Brown 1982 15 Women Gain the Right to Vote 1920 57 1984 Sally Ride and Final Frontier 1921 Birth Control Clinic Opens 16 58 Geraldine Ferraro Runs for VP 1984 17 Nellie Bly, Journalist 1922 60 Annie Oakley, Sharpshooter 1926 NOW: 20 Years Later 1928 Amelia Earhart Over Atlantic 18 Victoria Woodhull’s Legacy 1927 1986 61 Helen Keller’s New York 1932 62 Job Rights in Pregnancy Case 1987 19 1987 Facing the Subtler -

Women's Studies

A Guide to Historical Holdings in the Eisenhower Library WOMEN'S STUDIES Compiled by Barbara Constable April 1994 Guide to Women's Studies at the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library While the 1940s may conjure up images of "Rosie the Riveter" and women growing produce in their Victory Gardens on the homefront, the 1950s may be characterized as the era of June Cleaver and Harriet Nelson--women comfortable in the roles of mother and wife in the suburban neighborhoods of that era. The public statements concerning women's issues made by President Dwight D. Eisenhower show him to be a paradox: "...we look to the women of our land to start education properly among all our citizens. We look to them, I think, as the very foundation--the greatest workmen in the field of spiritual development...We have come a long ways in recognizing the equality of women. Unfortunately, in some respects, it is not yet complete. But I firmly believe it will soon be so." (Remarks at the College of Puget Sound, Tacoma, Washington, October 18, 1956) "I cannot imagine a greater responsibility, a greater opportunity than falls to the lot of the woman who is the central figure in the home. They, far more than the men, remind us of the values of decency, of fair play, of rightness, of our own self-respect--and respecting ourselves always ready to respect others. The debt that all men owe to women is not merely that through women we are brought forth on this world, it is because they have done far more than we have to sustain and teach those ideals that make our kind of life worth while." (Remarks at Business and Professional Women Meeting, Detroit, Michigan, October 17, 1960) "Today there are 22 million working women. -

General Files Series, 1932-75

GENERAL FILE SERIES Table of Contents Subseries Box Numbers Subseries Box Numbers Annual Files Annual Files 1933-36 1-3 1957 82-91 1937 3-4 1958 91-100 1938 4-5 1959 100-110 1939 5-7 1960 110-120 1940 7-9 1961 120-130 1941 9-10 1962 130-140 1942-43 10 1963 140-150 1946 10 1964 150-160 1947 11 1965 160-168 1948 11-12 1966 168-175 1949 13-23 1967 176-185 1950-53 24-53 Social File 186-201 1954 54-63 Subject File 202-238 1955 64-76 Foreign File 239-255 1956 76-82 Special File 255-263 JACQUELINE COCHRAN PAPERS GENERAL FILES SERIES CONTAINER LIST Box No. Contents Subseries I: Annual Files Sub-subseries 1: 1933-36 Files 1 Correspondence (Misc. planes) (1)(2) [Miscellaneous Correspondence 1933-36] [memo re JC’s crash at Indianapolis] [Financial Records 1934-35] (1)-(10) [maintenance of JC’s airplanes; arrangements for London - Melbourne race] Granville, Miller & DeLackner 1934 (1)-(7) 2 Granville, Miller & DeLackner 1935 (1)(2) Edmund Jakobi 1934 Re: G.B. Plane Return from England Just, G.W. 1934 Leonard, Royal (Harlan Hull) 1934 London Flight - General (1)-(12) London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables General (1)-(5) [cable file of Royal Leonard, FBO’s London agent, re preparations for race] 3 London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables Fueling Arrangements London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables Hangar Arrangements London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables Insurance [London - Melbourne Flight Instructions] (1)(2) McLeod, Fred B. [Fred McLeod Correspondence July - August 1934] (1)-(3) Joseph B. -

End of Year Review

End of Year Review 1 Table of Contents - Types of Communities Review - Types of Communities Sorting Activity - Then and Now Review Activity - Jobs in our Community Review Activity - Jobs in our Community Matching Activity - Goods and Services Sorting Activity - Continents of the World Map Activity - United States Map Activity - Symbols of the USA Review - Landmarks of the USA Matching Activity - President of the USA Activity - Leaders in our Community and Country Review - Leaders Sorting Activity - Holidays and Traditions Review - George Washington Carver Reading Comprehension Passage - Martin Luther King, Jr. Reading Comprehension Passage - Amelia Earhart Reading Comprehension Passage - Sally Ride Reading Comprehension Passage - Jackie Robinson Reading Comprehension Passage “Little School on the Range” © 2017 2 Types of Communities Name__________________________ Review Complete the statements using the words from the box below. RURAL URBAN SUBURBAN 1. In a rural farming community, the roads may be ____________________. 2. In urban or suburban communities, the roads are ___________________. 3. In urban areas, many people may not even own ___________ to get around. 4. In suburban areas, there are often _______________ for people to walk to places. 5. Buildings in rural areas are often spread out over large _______________. 6. People in large urban areas can travel places underground in the _________. 7. Suburban areas often have ________________ for children to play. 8. In rural communities, special equipment like ______________ may be used to help farmers. 9. In rural communities, people may have own farm animals like ___________. 10. In suburban communities, families can keep larger pets in their ________________. 11. In urban communities, families may have to own _____________ pets because there may not be room for larger pets. -

Jacqueline Cochran Crossword Manufacturing Beauty Products

Jacqueline Cochran acqueline Cochran is one of the most famous women in aviation history. She learned to y in only J three weeks. She later broke an existing altitude record by ying a biplane to 33,000 feet in the air. Jacqueline became very interested in air racing and participated in several races including the Bendix Cross Country Air Race. She had to convince Mr. Bendix to allow her to y since the race had been open to men pilots only. She won the race in 1937. Jacqueline also won speed records for ying. The most famous record she holds for speed was when she became the rst woman to break the sound barrier in 1953. She was named “the fastest woman in the world.” Before learning to y she had worked for several years in a beauty shop. She later began a company Jacqueline Cochran Crossword manufacturing beauty products. She named her company Jacqueline Cochran Cosmetics. When World War II began, Jacqueline was involved in testing new aviation equipment being devel- oped for the war. She also had the idea the military should include women as pilots during the war. acqueline Cochran is one of the most famous women in aviation history. She learned to fly in only After several meetings with the Chief of the Army Air Force General Hap Arnold , she was able to three weeks. She later broke an existing altitude record by flying a biplane to 33,000 feet in the air. J convince him to use women pilots to y non-combat missions. She became the director of the new Jacqueline became very interested in air racing and participatedorganization in several which races was named including the the Women Airforce Service Pilots ( WASP ). -

Presidential Documents 12711 Presidential Documents

Federal Register / Vol. 82, No. 42 / Monday, March 6, 2017 / Presidential Documents 12711 Presidential Documents Proclamation 9576 of March 1, 2017 Women’s History Month, 2017 By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation We are proud of our Nation’s achievements in promoting women’s full participation in all aspects of American life and are resolute in our commit- ment to supporting women’s continued advancement in America and around the world. America honors the celebrated women pioneers and leaders in our history, as well as those unsung women heroes of our daily lives. We honor those outstanding women, whose contributions to our Nation’s life, culture, history, economy, and families have shaped us and helped us fulfill America’s promise. We cherish the incredible accomplishments of early American women, who helped found our Nation and explore the great western frontier. Women have been steadfast throughout our battles to end slavery, as well as our battles abroad. And American women fought for the civil rights of women and others in the suffrage and civil rights movements. Millions of bold, fearless women have succeeded as entrepreneurs and in the workplace, all the while remaining the backbone of our families, our communities, and our country. During Women’s History Month, we pause to pay tribute to the remarkable women who prevailed over enormous barriers, paving the way for women of today to not only participate in but to lead and shape every facet of American life. Since our beginning, we have been blessed with courageous women like Henrietta Johnson, the first woman known to work as an artist in the colonies; Margaret Corbin, who bravely fought in the American Revolu- tion; and Abigail Adams, First Lady of the United States and trusted advisor to President John Adams. -

Theorizing the Transcendent Persona: Amelia Earhart's Vision In

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Faculty Research and Creative Activity Communication Studies January 2010 Theorizing the Transcendent Persona: Amelia Earhart’s Vision in The unF of It Robin E. Jensen Purdue University Erin F. Doss Purdue University Claudia Irene Janssen Eastern Illinois University, [email protected] Sherrema A. Bower Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/commstudies_fac Part of the Organizational Communication Commons Recommended Citation Jensen, Robin E.; Doss, Erin F.; Janssen, Claudia Irene; and Bower, Sherrema A., "Theorizing the Transcendent Persona: Amelia Earhart’s Vision in The unF of It" (2010). Faculty Research and Creative Activity. 6. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/commstudies_fac/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Studies at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Research and Creative Activity by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Theorizing the Transcendent Persona: Amelia Earhart’s Vision in The Fun of It Robin E. Jensen, Erin F. Doss, Claudia I. Janssen, & Sherrema A. Bower In this article, we define and theorize the ‘‘transcendent persona,’’ a discursive strategy in which a rhetor draws from a boundary-breaking accomplishment and utilizes the symbolic capital of that feat to persuasively delineate unconventional ways of communicating and behaving in society. Aviator Amelia Earhart’s autobiography The Fun of It (1932) functions as an instructive representative anecdote of this concept and demonstrates that the transcendent persona’s persuasive force hinges on one’s ability to balance distance from audiences with similarities to them. -

Freebies, Doodads, & Helpful Hints

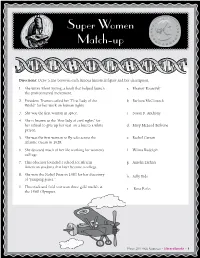

Super Women Match-up Directions: Draw a line between each famous historical figure and her description. 1. She wrote Silent Spring, a book that helped launch a. Eleanor Roosevelt the environmental movement. 2. President Truman called her “First Lady of the b. Barbara McClintock World” for her work on human rights. 3. She was the first woman in space. c. Susan B. Anthony 4. She is known as the “first lady of civil rights” for her refusal to give up her seat on a bus to a white d. Mary McLeod Bethune person. 5. She was the first woman to fly solo across the e. Rachel Carson Atlantic Ocean in 1928. 6. She devoted much of her life working for women’s f. Wilma Rudolph suffrage. 7. This educator founded a school for African g. Amelia Earhart American students that later became a college. 8. She won the Nobel Prize in 1983 for her discovery h. Sally Ride of “jumping genes.” 9. This track and field star won three gold medals at i. Rosa Parks the 1960 Olympics. March 2011 Web Resources • LibrarySparks • 1 Super Women Match-up Answer Key 1. She wrote Silent Spring, a book that helped a. Eleanor Roosevelt launch the environmental movement. 2. President Truman called her “First Lady b. Barbara McClintock of the World” for her work on human rights. 3. She was the first woman in space. c. Susan B. Anthony 4. She is known as the “first lady of civil rights” for her refusal to give up d. Mary McLeod Bethune her seat on a bus to a white person. -

![Biographies of Women Scientists for Young Readers. PUB DATE [94] NOTE 33P](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6994/biographies-of-women-scientists-for-young-readers-pub-date-94-note-33p-1256994.webp)

Biographies of Women Scientists for Young Readers. PUB DATE [94] NOTE 33P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 368 548 SE 054 054 AUTHOR Bettis, Catherine; Smith, Walter S. TITLE Biographies of Women Scientists for Young Readers. PUB DATE [94] NOTE 33p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Biographies; Elementary Secondary Education; Engineering Education; *Females; Role Models; Science Careers; Science Education; *Scientists ABSTRACT The participation of women in the physical sciences and engineering woefully lags behind that of men. One significant vehicle by which students learn to identify with various adult roles is through the literature they read. This annotated bibliography lists and describes biographies on women scientists primarily focusing on publications after 1980. The sections include: (1) anthropology, (2) astronomy,(3) aviation/aerospace engineering, (4) biology, (5) chemistry/physics, (6) computer science,(7) ecology, (8) ethology, (9) geology, and (10) medicine. (PR) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** 00 BIOGRAPHIES OF WOMEN SCIENTISTS FOR YOUNG READERS 00 "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY Once of Educational Research and Improvement Catherine Bettis 14 EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION Walter S. Smith CENTER (ERIC) Olathe, Kansas, USD 233 M The; document has been reproduced aS received from the person or organization originating it 0 Minor changes have been made to improve Walter S. Smith reproduction quality University of Kansas TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES Points of view or opinions stated in this docu. INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." ment do not necessarily rpresent official OE RI position or policy Since Title IX was legislated in 1972, enormous strides have been made in the participation of women in several science-related careers. -

Jacqueline Cochran Held More Speed, Altitude, and Distance Records Than Any Other Male Or Female Pilot in Aviation History…

¾ Aviation Pioneer ¾ Entrepreneur ¾ Leader ¾ Legend At the time of her death in 1980, Jacqueline Cochran held more speed, altitude, and distance records than any other male or female pilot in aviation history… Jacqueline Cochran’s record book will never…NEVER…be duplicated. GREATEST WOMEN This presentation chronicles “The PILOT!! Aviation Achievements of Ms. Jackie Cochran.” Jackie Cochran’s accomplishments match those of our Airpower legends ¾ Pilot License (1932) ¾ London to Melbourne (1934) ¾ First Bendix Race (1934) ¾ Accidents? . Yes! ¾ Discouraged? . No! Bendix Trophy... 1938 Harmon Trophy ¾ 1937 ¾ 1938 ¾ 1939 ¾ 1940-49 ¾ 1953 ¾ 1961 Test Pilot 1938-1942 ¾ P-38 ¾ P-47 ¾ P-51 ¾ B-17 ¾ British Air Transport Auxiliary (1941) ¾ President, “Ninety-Nines” (1941-1943) Director, US Women’s Flying Training… September 1942 Trained 1800 women for flight duty during WWII ¾ Founder/Director Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs)… July 1943 ¾ French Legion of Merit (1949) ¾ French Air Medal (1951) ¾ Decorated by 25 nations ¾ First Woman to break the Sound Barrier… ¾ 18 May 1953 ¾ First Woman to Land and then Take Off from an Aircraft Carrier ¾ A3D Skywarrior on USS Independence… 1960 ¾ President-Federation Aeronautique‘ Internationale (1958-61) ¾ Chairman-National Aeronautic Association (1962) ¾ First Woman to fly twice the speed of sound…3 June 1964 1429 nautical miles per hour!! ¾ World Altitude Record… 1961 55,253 feet!! ¾ Air Force Academy… 1975 National Aviation Hall of Fame (1971) Smithsonian (1981) Motorsports Hall of Fame (1993) Colonel in USAF Reserve Distinguished Service Medal (1945) Distinguished Flying Cross w/2 Oak Leaf Clusters (May 1969) Legion of Merit (1970) Additional Achievements Cosmetics Business (1932) Politics (1946) Frank M.