The Second National Woman's Rights Convention Worcester, MA October

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Matilda Joslyn Gage: Writing and “Righting” the History of Woman

20 MATILDA JOSLYN GAGE FOUNDATION FOUNDATION GAGE JOSLYN MATILDA Writing and Matilda the NWSA’s most active years and those spent writing the History.Volume IV minimized Gage’s activism and her contri- Joslyn bution to the History.For this reason, modern historians who have relied on Volume IV’s description of her work have Gage also tended to minimize Gage’s Gage’s role in that work alone contribution. BY MARY E. COREY should have guaranteed her a The rift between Gage and place of honor in our collective Anthony had its roots in the memory of the suffrage past. circumstances surrounding the Through a grand historic irony, one of Instead, it has obscured her formation of the NWSA in 1869. part in this and other move- Immediately following the the women most instrumental in the ment histories. Civil War, the reform alliance Volumes I, II, and III preserved between abolitionists and preservation of woman suffrage history the work of the National women’s rights advocates has herself been largely overlooked in Woman Suffrage Association crumbled in the fierce in-fight- from the beginnings of the ing over suffrage priorities. the histories of this movement. movement to about 1883. Unable to prevail on the issue Gage’s contributions to these of suffrage, Stanton, Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage was three volumes cannot be and Gage left the final American one of three National Woman overestimated. Her essays, Equal Rights Association Suffrage Association (NWSA) “Preceding Causes,”“Woman, Convention in May 1869 and founders who were known to Church and State,” and held an impromptu evening their contemporaries as the “Woman’s Patriotism in the War” session. -

The 19Th Amendment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Women Making History: The 19th Amendment Women The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. —19th Amendment to the United States Constitution In 1920, after decades of tireless activism by countless determined suffragists, American women were finally guaranteed the right to vote. The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. It was ratified by the states on August 18, 1920 and certified as an amendment to the US Constitution on August 26, 1920. Developed in partnership with the National Park Service, this publication weaves together multiple stories about the quest for women’s suffrage across the country, including those who opposed it, the role of allies and other civil rights movements, who was left behind, and how the battle differed in communities across the United States. Explore the complex history and pivotal moments that led to ratification of the 19th Amendment as well as the places where that history happened and its continued impact today. 0-31857-0 Cover Barcode-Arial.pdf 1 2/17/20 1:58 PM $14.95 ISBN 978-1-68184-267-7 51495 9 781681 842677 The National Park Service is a bureau within the Department Front cover: League of Women Voters poster, 1920. of the Interior. It preserves unimpaired the natural and Back cover: Mary B. Talbert, ca. 1901. cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work future generations. -

Lucy Stone 1818 – 1893 American a Project Based on Women Leading the Way: Suffragists & Suffragettes by Mireille Miller

lucy stone 1818 – 1893 American A Project based on Women Leading the Way: Suffragists & Suffragettes by Mireille Miller. biographie biography Saviez-vous que l’enfance de Lucy Stone et son éducation Did you know that Lucy Stone’s background and education l’ont aidée à former son futur? Et qu’elle a contribué aux helped her shape her future? And that she contributed to associations des droits des femmes et aux associations anti- women’s rights associations and antislavery associations? Or that esclavagistes ? Où qu’elle était surnommée “Pionnière du Suffrage she was titled “Pioneer of Women’s Suffrage” for all that she had des Femmes” pour tout ce qu’elle avait fait ? done? Dès son plus jeune âge, Lucy Stone a toujours su ce qu’elle Lucy Stone always knew what she wanted to accomplish while she voulait faire. Née à West Brookfield dans le Massachusetts, le 13 août was growing up. Born in West Brookfield, Massachusetts, August 13, 1818, elle a grandi là tout au long de son enfance. A l’âge de 16 ans, 1818, she grew up there throughout her childhood. When she was the Stone fut une maîtresse pendant 9 ans, et elle économisait son argent pour age of 16, Stone was a teacher for 9 years, saving her money to work on travailler sur les droits des femmes et des esclaves. Elle a terminé ses études women’s rights and antislavery. She finished her education in 1847 at Oberlin en 1847 à Oberlin Collège avec l’aide de son père. Elle a été la première femme en College with help from her father. -

Carol Inskeep's Book List on Woman's Suffrage

Women’s Lives & the Struggle for Equality: Resources from Local Libraries Carol Inskeep / Urbana Free Library / [email protected] Cartoon from the Champaign News Gazette on September 29, 1920 (above); Members of the Chicago Teachers’ Federation participate in a Suffrage Parade (right); Five thousand women march down Michigan Avenue in the rain to the Republican Party Convention hall in 1916 to demand a Woman Suffrage plank in the party platform (below). General History of Women’s Suffrage Failure is Impossible: The History of American Women’s Rights by Martha E. Kendall. 2001. EMJ From Booklist - This volume in the People's History series reviews the history of the women's rights movement in America, beginning with a discussion of women's legal status among the Puritans of Boston, then highlighting developments to the present. Kendall describes women's efforts to secure the right to own property, hold jobs, and gain equal protection under the law, and takes a look at the suffrage movement and legal actions that have helped women gain control of their reproductive rights. She also compares the lifestyles of female Native Americans and slaves with those of other American women at the time. Numerous sepia photographs and illustrations show significant events and give face to important contributors to the movement. The appended list of remarkable women, a time line, and bibliographies will further assist report writers. Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Women’s Rights Movement by Sally G. McMillen. 2008. S A very readable and engaging account that combines excellent scholarship with accessible and engaging writing. -

Creating a Primary Source Lesson Plan

Women’s Fight for Equality Katy Mullen and Scott Gudgel Stoughton High School London arrest of suffragette. Bain News Service. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, reproduction number LC-DIG-ggbain-10397, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ggbain.10397/ This unit on women in US History examines gender roles, gender stereotypes, and interpretations of significant events in women’s history. This leads students to discover gender roles in contemporary society. Overview Objectives: Students will: Knowledge • Analyze women’s history and liberation • Analyze the different interpretations of significant historical events Objectives: Students will: Skills • Demonstrate critical thinking skills • Develop writing skills • Collaborative Group work skills Essential “Has the role of women changed in the United States?” Question Recommended 13 50-minute class periods time frame Grade level 10th –12th grade Materials Copies of handouts Personal Laptops for students to work on Missing! PowerPoint. Library time Wisconsin State Standards B.12.2 Analyze primary and secondary sources related to a historical question to evaluate their relevance, make comparisons, integrate new information with prior knowledge, and come to a reasoned conclusion B.12.3 Recall, select, and analyze significant historical periods and the relationships among them B.12.4 Assess the validity of different interpretations of significant historical events B.12.5 Gather various types of historical evidence, including visual and quantitative data, to analyze issues of -

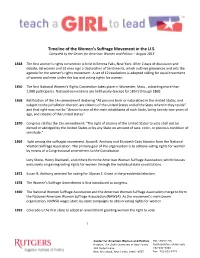

Timeline of the Women's Suffrage Movement in the U.S

Timeline of the Women’s Suffrage Movement in the U.S. Compiled by the Center for American Women and Politics – August 2014 1848 The first women's rights convention is held in Seneca Falls, New York. After 2 days of discussion and debate, 68 women and 32 men sign a Declaration of Sentiments, which outlines grievances and sets the agenda for the women's rights movement. A set of 12 resolutions is adopted calling for equal treatment of women and men under the law and voting rights for women. 1850 The first National Women's Rights Convention takes place in Worcester, Mass., attracting more than 1,000 participants. National conventions are held yearly (except for 1857) through 1860. 1868 Ratification of the 14th amendment declaring “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside” and that right may not be “denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States” 1870 Congress ratifies the 15th amendment: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” 1869 Split among the suffragist movement. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton form the National Woman Suffrage Association. The primary goal of the organization is to achieve voting rights for women by means of a Congressional amendment to the Constitution. -

Massachusetts Leadership in the Woman Suffrage Movment

copyright Barbara F 1 Berenson Themes from Within Movement • Key Events • Leaders (top down) • Foot Soldiers (bottom up) • Diversity of Participants copyright Barbara F 2 Berenson The Women’s Rights Movement Emerges within MA Anti-Slavery Movement © Barbara F. Berenson 2018 The Grimké Sisters Angelina Grimké Sarah Grimké © Barbara F. Berenson 2018 Boston: Abolitionist Center William Lloyd Garrison © Barbara F. Berenson 2018 Congregational Ministers Letter, 1837 “When she assumes the place and tone of a man as a public reformer . Her character becomes unnatural . and the way is opened for degeneracy and ruin.” © Barbara F. Berenson 2018 Letters of the Grimké Sisters Sarah Grimké Angelina Grimké “I contend that woman has “There are few things which just as much right to sit in present greater obstacles to solemn counsel in Conventions, the improvement and Conferences, Associations and elevation of woman to her General Assemblies, as man – appropriate sphere of just as much right . [to sit] in usefulness and duty than the . the Presidential chair of the .[laws which] she has had no United States.” voice in establishing.” © Barbara F. Berenson 2018 Orators to Organizers The Organized Woman Suffrage Movement was Launched in Worcester in 1850 © Barbara F. Berenson 2018 Lucy Stone © Barbara F. Berenson 2018 First National Women’s Rights Convention Worcester 1850 Brinley Hall © Barbara F. Berenson 2018 Movement Suspended During Civil War, But . © Barbara F. Berenson 2018 Women’s Roles Expanded During the Civil War © Barbara F. Berenson 2018 Schism Over the 15th Amendment Founding of AWSA © Barbara F. Berenson 2018 Schism over the 15th Amendment © Barbara F. -

The Worcester Womens Rights Convention

THE WORCESTER WOMENS RIGHTS CONVENTION OF 1850: A SOCIAL ANALYSIS OF THE RANK AND FILE MEMBERSHIP By HOLLY N. BROWN Bachelor of Arts University of Kentucky Lexington, Kentucky 1994 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTERS OF ARTS May, 1997 THE WORCESTER WOMENS RIGHTS CONVENTION OF 1850: A SOCIAL ANALYSIS OF THE RANK AND FILE MEMBERSHIP Thesis Approved: . ~ 1t1'J~ cd ~~ Dean of the Graduate College 11 PREFACE This study analyzed the membership of the Worcester Women's Rights Convention of 1850, to compare the major characteristics of this group to the general population of Worcester, Massachusetts in 1850. The members of the convention were urban, white, Protestant and different from the general population. The city of Worcester's population was much more diverse. Within the membership group it was found that they were not all of the same socio-economic background. By dividing the one group into three categories--antislavery organizers, women, and men--the study found that there were working class as well as upper and middle class individuals at the convention. The class diversity occurred almost wholly among women. The bulk of the research of this study was conducted at the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts. Sources were also located at the Worcester Historical Museum and the Worcester Room at the Worcester Public Library. 111 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my sincere appreciation to my major advisor, Dr. James Huston for his intelligent supervision, constructive guidance, and for his time and effort in my education on quantification. -

Books About Women's Suffrage Movement, Women's Rights

Books About Women’s Suffrage Movement, Women’s Rights, League of Women Voters, and Related Children’s Books Woman’s Suffrage The Woman’s Hour: The Great The book covers the struggle Fight to Win the Vote between opposing forces at the by Elaine Weiss (2018) apex of the struggle for women’s suffrage in 1920, after a seven- decade effort. You feel like you are there in this exciting format. It all comes down to Tennessee… Note: A television movie in collaboration with Hillary Rodham Clinton is in the works for 2020. Mr. President, How Long Must This book explores the We Wait?: Alice Paul, Woodrow interaction of suffragist Alice Paul Wilson, and the Fight for the and President Woodrow Wilson, Right to Vote as women demonstrated for the by Tina Cassidy (2019) right to vote in front of the White House. It combines details about Ms. Cassidy is local and may be “what it was like” with in depth available to discuss her book. descriptions of the backgrounds of the two personalities. Consider watching the HBO movie Iron Jawed Angels also, about the same period and events. A Woman’s Place Is at the Top: A Thoroughly enjoyable book about Biography of Annie Smith Peck, a little-known mountain climber Queen of the Climbers and suffragist. by Hannah Kimberley (2017) Ms. Kimberley is a member of the Cape Ann League and has spoken at several League events in the North Shore area. www.hannahkimberley.com 1 The Women’s Suffrage Movement This book is a diverse anthology by Sally Roesch Wagner (2019) of women’s voices both known and unknown related to the The author is the founding history of women’s director of the Matilda Joslyn enfranchisement, including Gage Foundation, and serves on African American suffragists and the New York State Women's Native American women with a Suffrage Commission. -

Women Rabbis

------------------------------------------------... ~)l.,.""' Women Rabbis: frOIH Alltoil'lette Brown Blackwell Exploration & celebration to sally priesaHd: All Hislorical pcrsyectivc Oil the Emctgellce (if WOlILell iH lhe AmericalL RabbilLate Papers Delivered at an JOllatJlIlII D. Santll AcaJelnic Conference Honoring Twenty Years of In planlling to speak .It this cOllfCrcllu,:, thc (Iucstioll naturally arosc as W01l1en in the Rabbinate to how Ellcll U lIlansk y and I should dividc thc subject of the histodcal background to the cmcrgcncc of womcll in the American rabbinate. Ellell 1972-1992 and I spoke, and we decidcd Oil what seclIH.:d like a lair 50-50 division: she took Oil the Jewish a,~pects 0(' the story, and I agreed to cover everything else. My story hegins early in the nineteenth century Juring the period known to American religious historians as the Second Great Awakening. In some respects, this was an era similar to our own: a time of remarkable religious Edited by change, with thousands or individuals undergoing religious revival (today we would say that they were "born again"), ami a timc whcn American Gary P. zola religion itself was beillg transli>rlll<.:d with th<.: growth of new religious movemellts (some or which started as ohsl:ure sects and cults) and the ;)cc<.:ptancc of a host of new ide;)s. The most important of these ideas, II)r our purposes, was a diminished belief ill predestination and innate human II uc-JI R Rabbinic Alumni Association Press depraVity and a gr<.:atcr emphasis on the ability of human heings, through their OWIl ('nill-t.~, to dlangc alld improve th<.: world. -

Key Terms and People Lesson Summary

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-A Name ________________________________ Class ____________________ Date _____________ Reform Movements in the United States Lesson 5 MAIN IDEAS 1. Influenced by the abolition movement, many women struggled to gain equal rights for themselves. 2. Calls for women’s rights met opposition from men and women. 3. The Seneca Falls Convention launched the first organized women’s rights movement in the United States. Key Terms and People Elizabeth Cady Stanton supporter of women’s rights who helped organize the Seneca Falls Convention; co-founder of Woman Suffrage Association Seneca Falls Convention the first organized public meeting about women’s rights held in the United States Declaration of Sentiments document officially requesting equal rights for women Lucy Stone spokesperson for the Anti-Slavery Society and the women’s rights movement; co-founder of Woman Suffrage Association Susan B. Anthony women’s rights supporter who argued for equal pay for equal work, the right of women to enter male professions, and property rights Matilda Joslyn Gage co-founder of National Woman Suffrage Association; writer and advocate for women’s rights Lesson Summary WOMEN’S STRUGGLE FOR EQUAL RIGHTS Why did critics of the In the mid-1800s, some female abolitionists also Grimké sisters think began to focus on the women’s rights in America, women should not speak in public? despite their many critics. For example, the __________________________ Grimké sisters were criticized for speaking in public. Their critics felt they should stay at home. __________________________ Sarah Grimké responded by writing a pamphlet in support of women’s rights. -

The Struggle for Women's Rights

THE STRUGGLE FOR WOMEN'S RIGHTS women’s rights but to seize By our civil rights editor them, “as did our fathers against October 25, 1850 King George III.” Sojourner HE first annual National Truth, the abolitionist born into Women’s Rights Convention slavery, gave a rousing speech Tended in triumph yesterday. on women’s rights. At the historic gathering in Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a Worcester, delegates from 11 U.S. leader in the women’s rights states heard speeches on women’s movement, was unable to attend right to vote as well as their right due to her pregnancy, but sent a to equal wages and to own property. letter of support: “The earth has Both women and men attended never yet seen a truly great and the two-day convention at Brinley virtuous nation, for woman has Hall, which attracted activists never yet stood the equal with man.” from as far away as the new U.S. Others who attended were state of California. abolitionists Frederick Douglass The press, sensing a good story, and William Lloyd Garrison. were not always kind to the Nantucket-born Lucretia Mott, participants. One newspaper who had helped to organize the called them a “motley mingling.” Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, Lucy Stone (right), of West the first regional women’s rights Brookfield—the first woman convention, also attended. from Massachusetts to earn a and to own property. Ernestine Fathers … but who has heard of The gathering in Worcester is college degree—was one of the Rose, who fled Poland for the Pilgrim Mothers?” surely not the last: women are main organizers.