WORKPACKAGE No. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulgaria – the Difficult “Return to Europe”

European Democracy in Action BULGARIA – THE DIFFICULT “RETURN TO EUROPE” TAMARA BUSCHEK Against the background of the EU accession of Bulgaria on 1st January 2007 and the first Bulgarian elections for the European Parliament on 20th May 2007, Tamara Buschek takes a closer look at Bulgaria’s uneven political and economic transition – at its difficult “return to Europe”. Graduated from Graz University (Austria) in 2003 with a Masters in Law [magistra juris] after finishing her studies in European and international law. After gaining a grant from the Chamber of Commerce in 2000 to complete an internship at the Austrian Embassy in London, she carried out research for her dissertation in criminal law – “The Prevention of Sexual Child Abuse – Austria/Great Britain” - in 2001 at the London School of Economics. She studied European and administrative law in Paris from 2001 to 2002 as part of an Erasmus year. She is quadrilingual (German, Bulgarian, English and French). « BULGARIA – THE DIFFICULT RETURN TO EUROPE » MAY 2007 Table of Contents Introduction P. 1 2.3 The current governmental coalition, 2005-2007 and the P. 21 presidential election in 2006 I – Background Information P. 3 III - The first European Parliament elections, 20 May 2007 P. 25 1.1 Hopes and Fears P. 3 Conclusion P. 30 1.2 Ethnic Minorities P. 5 1.3 Economic Facts P. 7 Annex P. 32 II – Political Situation- a difficult path towards stability P. 9 Annex 1: Key facts P. 32 2.1 The transition from 1989 till 2001 P. 9 Annex 2: Economic Profile P. 33 2.1.1 The legislative elections of 1990 and the first P. -

There Has Been No Bulgarian Tradition of Any Long-Standing Resistance to the Communist Regime

There has been no Bulgarian tradition of any long-standing resistance to the communist regime. There was neither any political opposition, nor any other kind of an influential dissident movement. Bulgaria never went through the purgatory of the Hungarian uprising of 1956, or the “Prague spring” of 1968. It is indeed difficult to find any counter arguments whatsoever against the cliché that Bul- garia was the closest satellite of the Soviet Union. The fundamental contradictions within the Union of Democratic Forces (SDS) coalition were present from the very first day of its inception. There were Marxists who were longing for “socialism with a human face”, intellectuals with liberal ideas, social democrats and Christian democrats, conservatives and radical demo- crats, monarchists and republicans. The members of the center-right coalition did not delude themselves about their differences; they rather shared the clear un- derstanding that only a painful compromise could stand some chances against the Goliath of the totalitarian Bulgarian Communist Party (BKP). It was this unani- mous opposition to the communist regime and its legacy that made the coalition possible. But only for a limited period of time. The United Democratic Forces (ODS) government under Prime Minister Ivan Kostov (1997-2001) completed the reformist agenda of anti-communism. At the end of the ODS term of office, Bulgaria was a country with a functioning market economy, stable democracy, and a clearly outlined foreign policy course towards the country’s accession to the European Union and NATO, which was accepted by all significant political formations, the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP) included. -

General Election in Bulgaria

GENERAL ELECTIONS IN BULGARIA 26th March 2017 European The Bulgarian general elections on 26th Elections monitor March might not lead to a majority Corinne Deloy On 24th January the new President of the Republic of Bulgaria, Rumen Radev, elected on 13th November 2016, dissolved the National Assembly (Narodno sabranie), the only chamber of Parliament in Bulgaria and convened a snap election on 26th March. This will be the third since 2013. According to political analysts it might not lead to a strong majority able to Analysis implement the economic and institutional reform that Bulgaria so badly needs. “None of the parties seem able to win an absolute majority which, will lead to a divided parliament and a weak government coalition,” indicated Andrius Tursa, a political expert of the consultancy Teneo. Outgoing Prime Minister Boyko Borissov, (Citizens for the European Development of Bulgaria, GERB), deemed that it would certainly be difficult to form a government after the election. 12 parties and 9 coalitions are running in these parliament leader as its head (2001-2005) elections. According to the most recent poll whose task it has been to prepare for the by Trend, the GERB is running neck and neck upcoming general elections and to ensure the with the Socialist Party (BSP) with 29.7% and smooth running of the State until his successor 28.7% respectively. The Patriotic Front stands is appointed. third with 9.9% of the vote, followed by the An extremely unstable political scene Movement for Rights and Liberties (DPS), a party representing the Turkish minority, is due Boyko Borissov is the first head of the Bulgarian to win 9%. -

Bulgaria: Country Background Report

Order Code 98-627 F Updated July 13, 2001 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Bulgaria: Country Background Report -name redacted- Specialist in International Relations Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary In June 2001, the party of Simeon II, Bulgaria’s former King from the pre- communist era, won just short of a majority of the vote in parliamentary elections. Simeon, who founded his party three months earlier, did not run for a seat in parliament, but nevertheless was nominated by his party on July 12 to become Prime Minister. Simeon II is the first ex-monarch to return to power in eastern Europe since World War II. The Simeon II National Movement party replaces a center-right government that achieved many significant economic reforms and consolidated Bulgaria’s pro-Western orientation. Primary goals for Bulgaria remain full membership in NATO and the European Union. U.S. Administrations and Congress have noted Bulgaria’s positive role in promoting peace and stability in the Balkan region. This report will be updated as events warrant. Background From the 14th to the 19th century, Bulgaria was part of the Ottoman empire. It gained independence in the late 19th century. Bulgaria was on the losing side of three wars in the 20th century and came under communist rule in 1944. During the Cold War, Bulgaria had the reputation of being the Soviet Union’s most stalwart ally in the Warsaw Pact. Todor Zhivkov, head of the Bulgarian Communist Party, led a repressive regime in Bulgaria for 35 years. Beginning in 1989, Bulgaria began a gradual process of transformation to a democratic and market economic state that progressed more slowly than in other central European countries (such as Poland or Hungary), but with no violent changes in power as in Romania or Yugoslavia. -

Appendix 1A: List of Government Parties September 12, 2016

Updating the Party Government data set‡ Public Release Version 2.0 Appendix 1a: List of Government Parties September 12, 2016 Katsunori Seki§ Laron K. Williams¶ ‡If you use this data set, please cite: Seki, Katsunori and Laron K. Williams. 2014. “Updating the Party Government Data Set.” Electoral Studies. 34: 270–279. §Collaborative Research Center SFB 884, University of Mannheim; [email protected] ¶Department of Political Science, University of Missouri; [email protected] List of Government Parties Notes: This appendix presents the list of government parties that appear in “Data Set 1: Governments.” Since the purpose of this appendix is to list parties that were in government, no information is provided for parties that have never been in government in our sample (i.e, opposition parties). This is an updated and revised list of government parties and their ideological position that were first provided by WKB (2011). Therefore, countries that did not appear in WKB (2011) have no list of government parties in this update. Those countries include Bangladesh, Botswana, Czechoslovakia, Guyana, Jamaica, Namibia, Pakistan, South Africa, and Sri Lanka. For some countries in which new parties are frequently formed and/or political parties are frequently dissolved, we noted the year (and month) in which a political party was established. Note that this was done in order to facilitate our data collection, and therefore that information is not comprehensive. 2 Australia List of Governing Parties Australian Labor Party ALP Country Party -

Ethno-Nationalism During Democratic Transition in Bulgaria: Political Pluralism As an Effective Remedy for Ethnic Conflict

Ethno-Nationalism during Democratic Transition in Bulgaria: Political Pluralism as an Effective Remedy for Ethnic Conflict Bistra-Beatrix Volgyi Department of Political Science York University YCISS Post-Communist Studies Programme Research Paper Series Paper Number 003 March 2007 Research Papers Series publishes research papers on problems of post-communism written by graduate and undergraduate students at York University. Following the collapse of communism in the 1990s in Central and South- Eastern Europe, the region has not only undergone a difficult period of economic and political transition, but also has witnessed the rise of ethno-nationalism in several states, along with problems of national identity, state formation and the exclusion (or extermination as in the Yugoslav case) of minorities. Nationalism may adopt a variety of forms simultaneously - ethnic, cultural or civic, where either one of these forms or a mixture of elements from the three, may predominate in a state over time, influenced by politico-economic realities, elite behavior, party coalitions, international interests and ideological influences, as well as societal attitudes. Nationalism in its ethnic variant has led to the alienation and violation of minorities’ rights, and its supporters have advocated the creation of ethnically homogenous states. Proponents of cultural nationalism have attempted the assimilation of national minority ‘low cultures’ into the dominant national ‘high culture.’ On the other hand, civic nationalism has mobilized people in Eastern -

Cominform 1947

For A Lasting Peace, For A People’s Democracy FOR A LASTING PEACE, FOR A PEOPLE’S DEMOCRACY Full and complete Reports submitted to the Nine Communist Parties’ Conference held at Warsaw in September 1947 PEOPLE’S PUBLISHING HOUSE, LTD. Bombay, 1948 First Indian Edition March 1948 PUBLISHER’S NOTE We are printing in the following pages the full reports as submitted by the representa- tives of the leading Communist Parties of Europe who attended the Informatory Con- ference held in Warsaw towards the end of September 1947. They have been taken from the fortnightly organ of the Commu- nist Information Bureau, For A Lasting Peace, For A People’s Democracy!—Nos. 1, 2, 3, and 4. CONTENTS COMMUNIQUÉ ....................................................................................................1 DECLARATION ....................................................................................................2 RESOLUTION ......................................................................................................5 EDVARD KARDELJ: The Communist Party of Yugoslavia in the Struggle for the Independence of the Yugoslav Peoples.... and Socialist Reconstruction of the Economy ...............................................6 1. The Party in the Period of the National Liberation War ............................................... 7 2. The Role of the Party in the Political and Economic Construction of the New Yugoslavia .................................................................................................................... 18 WLADISLAW -

Bulgaria: Neither a Protest, Nor a European Vote Nikoleta Yordanova

Bulgaria: neither a protest, nor a European vote nikoleta yordanova In May 2019, over six million voters were eligible to select seventeen members of the European Parliament (EP) in Bulgaria under a proportional representation system with preferential voting in a single nation-wide constituency.1 Three hundred and eighteen candidates were nominated by thirteen political parties, eight coalitions and six initiative committees.2 Voting in the EP elections is mandatory in Bulgaria, but there is no penalty for not turning out to vote. Furthermore, voting can take place only in person at polling stations and there is no postal voting. These voting arran- gements, combined with the lack of any new political formations to mobilise habi- tual non-voters and the fact that the election fell on the third day of a long weekend, prompted low electoral turnout.3 the electoral campaign Until election day, the winner of the European elections in Bulgaria was unpredic- table. A week before the elections, one fourth of the voters were undecided.4 The main governing political party, Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB), in coalition with the United Democratic Forces (SDS), was predicted by opinion polls to receive 30%. So was the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), the biggest opposition party and a successor of the ex-communist party. A distant third, but sure to obtain EP representation (polling at about 11%), was the long-standing Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS), representing the ethnic Turkish minority in Bulgaria. A num- ber of smaller parties and independent candidates fought for single seats. Most likely to pass the 5.88% effective threshold needed to obtain a seat were the “Democratic 1. -

A Concise History of Bulgaria, Second Edition R

Cambridge University Press 0521616379 - A Concise History of Bulgaria, Second Edition R. J. Crampton Index More information INDEX aba 55, 56, 65 129, 133, 137, 139–40, 142, 143, Academy of Sciences 151 144, 145, 147, 152, 158, 159, ACC (Allied Control Commission) 180, 160–1, 166, 168–71, 175, 179, 189, 181 190, 193, 214, 215, 219, 241, 253, Adrianople (Edirne) 24, 27, 53, 55, 83, 265 106, 114, 128, 133, 135 and communists 180, 183 Adriatic 16, 22, 25, 262 Asenov, Hadji Dimituˆr76 Aegean coast 26, 83, 135, 169 Asia Minor 10, 11, 20, 56 Aegean Sea 4, 16, 25, 135 Asparukh, Khan 8 Aegean Sea, Bulgarian access to 144, Atanasov, Georgi 239 164, 166 Athens 73, 75, 157, 161 Afghanistan 253, 261 Athos, Mount 39, 45 agrarians 145–7, 156, 161, 162, 174, Austria-Hungary 17, 83, 126, 127, 128, 175, 179, 182–3, 212, 214, 215 130, 131 see also BANU and BANU–NP see also Habsburg monarchy AICs (Agro-Industrial Complexes) ayans 51, 52, 53, 55 197–8 Albania (Albanians) 11, 20, 22, 71, 131, Bagryanov, Ivan 176–7 133, 241 Balchik 133 Aleksanduˆr Nevski cathedral 220 Balkan alliance 73, 131–2 Alexander II, Tsar of Russia 90 entente 157, 165, 235 AlexanderIII,TsarofRussia90, 101, 110 federation 76, 77, 125, 126, 190 Alexander of Battenberg, Prince of mountains 4, 9, 13, 53, 72, 77, 83, 99, Bulgaria 89–93, 94, 97, 97–9, 113, 115 100–1, 102, 105, 108, 119, 121, peacekeeping force 241 265 Balkan war, first 132–3 Alexander the Great 4 second 134–5, 158, 266 Alexandroupolis 230, 262 banks and banking 118, 122, 148, 159, alphabet (Cyrillic and Bulgarian) 15, 186, -

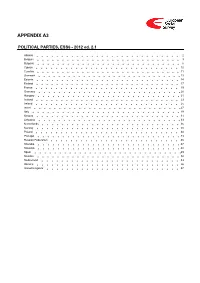

ESS6 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS6 - 2012 ed. 2.1 Albania 2 Belgium 3 Bulgaria 6 Cyprus 10 Czechia 11 Denmark 13 Estonia 14 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Israel 27 Italy 29 Kosovo 31 Lithuania 33 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 43 Russian Federation 45 Slovakia 47 Slovenia 48 Spain 49 Sweden 52 Switzerland 53 Ukraine 56 United Kingdom 57 Albania 1. Political parties Language used in data file: Albanian Year of last election: 2009 Official party names, English 1. Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë (PS) - The Socialist Party of Albania - 40,85 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Partia Demokratike e Shqipërisë (PD) - The Democratic Party of Albania - 40,18 % election: 3. Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim (LSI) - The Socialist Movement for Integration - 4,85 % 4. Partia Republikane e Shqipërisë (PR) - The Republican Party of Albania - 2,11 % 5. Partia Socialdemokrate e Shqipërisë (PSD) - The Social Democratic Party of Albania - 1,76 % 6. Partia Drejtësi, Integrim dhe Unitet (PDIU) - The Party for Justice, Integration and Unity - 0,95 % 7. Partia Bashkimi për të Drejtat e Njeriut (PBDNJ) - The Unity for Human Rights Party - 1,19 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Socialist Party of Albania (Albanian: Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë), is a social- above democratic political party in Albania; it is the leading opposition party in Albania. It seated 66 MPs in the 2009 Albanian parliament (out of a total of 140). It achieved power in 1997 after a political crisis and governmental realignment. In the 2001 General Election it secured 73 seats in the Parliament, which enabled it to form the Government. -

CSESII Parties and Leaders Original CSES Text Plus CCNER Additions (Highlighted)

CSESII Parties and Leaders Original CSES text plus CCNER additions (highlighted) =========================================================================== ))) APPENDIX I: PARTIES AND LEADERS =========================================================================== | NOTES: PARTIES AND LEADERS | | This appendix identifies parties active during a polity's | election and (where available) their leaders. | | Provided are the party labels for the codes used in the micro | data variables. Parties A through F are the six most popular | parties, listed in descending order according to their share of | the popular vote in the "lowest" level election held (i.e., | wherever possible, the first segment of the lower house). | | Note that in countries represented with more than a single | election study the order of parties may change between the two | elections. | | Leaders A through F are the corresponding party leaders or | presidential candidates referred to in the micro data items. | This appendix reports these names and party affiliations. | | Parties G, H, and I are supplemental parties and leaders | voluntarily provided by some election studies. However, these | are in no particular order. --------------------------------------------------------------------------- >>> PARTIES AND LEADERS: ALBANIA (2005) --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 02. Party A PD Democratic Party Sali Berisha 01. Party B PS Socialist Party Fatos Nano 04. Party C PR Republican Party Fatmir Mediu 05. Party D PSD Social Democratic Party Skender Gjinushi 03. Party E LSI Socialist Movement for Integration Ilir Meta 10. Party F PDR New Democratic Party Genc Pollo 09. Party G PAA Agrarian Party Lufter Xhuveli 08. Party H PAD Democratic Alliance Party Neritan Ceka 07. Party I PDK Christian Democratic Party Nikolle Lesi 06. LZhK Movement of Leka Zogu I Leka Zogu 11. PBDNj Human Rights Union Party 12. Union for Victory (Partia Demokratike+ PR+PLL+PBK+PBL) 89. -

Macro Report Version 2002-10-23

Prepared by: Balkan British Social Surveys, Gallup International Bulgaria Date: 22nd April 2003 Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 2: Macro Report Version 2002-10-23 Country (Date of Election): 17. June 2001 NOTE TO THE COLLABORATORS: The information provided in this report contributes to an important part of the CSES project- your efforts in providing these data are greatly appreciated! Any supplementary documents that you can provide (i.e. electoral legislation, party manifestos, electoral commission reports, media reports) are also appreciated, and will be made available with this report to the CSES community on the CSES web page. Part I: Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was administered 1. Report the number of portfolios (cabinet posts) held by each party in cabinet, prior to the most recent election. (If one party holds all cabinet posts, simply write "all".) Name of Political Party Number of Portfolios UDF– United Democratic Forces ALL 1a. What was the size of the cabinet before the election?……14 ministries 2. Report the number of portfolios (cabinet posts) held by each party in cabinet, after the most recent election. (If one party holds all cabinet posts, simply write "all"). Name of Political Party Number of Portfolios United Democratic Forces (UDF) None Coalition for Bulgaria 2 (one resigned later) National Movement Simeon the Second (NMS II) 16 Movement for Rights & Freedom (MRF) 2 Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 2 Module 2: Macro Report 2a. What was the size of the cabinet after the election? 19 ministries 3. Political Parties (most active during the election in which the module was administered and receiving at least 3%* of the vote): Party Name/Label Year Party Ideological European Parliament Political International Founded Family Group Party (where applicable) Organizational Memberships A.