Political Parties in Central and Eastern Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poland (Mainly) Chooses Stability and Continuity: the October 2011 Polish Parliamentary Election

Poland (mainly) chooses stability and continuity: The October 2011 Polish parliamentary election Aleks Szczerbiak [email protected] University of Sussex SEI Working Paper No. 129 1 The Sussex European Institute publishes Working Papers (ISSN 1350-4649) to make research results, accounts of work-in-progress and background information available to those concerned with contemporary European issues. The Institute does not express opinions of its own; the views expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the author. The Sussex European Institute, founded in Autumn 1992, is a research and graduate teaching centre of the University of Sussex, specialising in studies of contemporary Europe, particularly in the social sciences and contemporary history. The SEI has a developing research programme which defines Europe broadly and seeks to draw on the contributions of a range of disciplines to the understanding of contemporary Europe. The SEI draws on the expertise of many faculty members from the University, as well as on those of its own staff and visiting fellows. In addition, the SEI provides one-year MA courses in Contemporary European Studies and European Politics and opportunities for MPhil and DPhil research degrees. http://www.sussex.ac.uk/sei/ First published in March 2012 by the Sussex European Institute University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton BN1 9RG Tel: 01273 678578 Fax: 01273 678571 E-mail: [email protected] © Sussex European Institute Ordering Details The price of this Working Paper is £5.00 plus postage and packing. Orders should be sent to the Sussex European Institute, University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton BN1 9RG. -

Romanian Political Science Review Vol. XXI, No. 1 2021

Romanian Political Science Review vol. XXI, no. 1 2021 The end of the Cold War, and the extinction of communism both as an ideology and a practice of government, not only have made possible an unparalleled experiment in building a democratic order in Central and Eastern Europe, but have opened up a most extraordinary intellectual opportunity: to understand, compare and eventually appraise what had previously been neither understandable nor comparable. Studia Politica. Romanian Political Science Review was established in the realization that the problems and concerns of both new and old democracies are beginning to converge. The journal fosters the work of the first generations of Romanian political scientists permeated by a sense of critical engagement with European and American intellectual and political traditions that inspired and explained the modern notions of democracy, pluralism, political liberty, individual freedom, and civil rights. Believing that ideas do matter, the Editors share a common commitment as intellectuals and scholars to try to shed light on the major political problems facing Romania, a country that has recently undergone unprecedented political and social changes. They think of Studia Politica. Romanian Political Science Review as a challenge and a mandate to be involved in scholarly issues of fundamental importance, related not only to the democratization of Romanian polity and politics, to the “great transformation” that is taking place in Central and Eastern Europe, but also to the make-over of the assumptions and prospects of their discipline. They hope to be joined in by those scholars in other countries who feel that the demise of communism calls for a new political science able to reassess the very foundations of democratic ideals and procedures. -

Central and Eastern Europe Development Outlook After the Coronavirus Pandemic

CHINA-CEE INSTITUTE CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE DEVELOPMENT OUTLOOK AFTER THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC Editor in Chief: Dr. Chen Xin Published by: China-CEE Institute Nonprofit Ltd. Telephone: +36-1-5858-690 E-mail: [email protected] Webpage: www.china-cee.eu Address: 1052, Budapest, Petőfi Sándor utca 11. Chief Editor: Dr. Chen Xin ISSN: 978-615-6124-29-6 Cover design: PONT co.lab Copyright: China-CEE Institute Nonprofit Ltd. The reproduction of the study or parts of the study are prohibited. The findings of the study may only be cited if the source is acknowledged. Central and Eastern Europe Development Outlook after the Coronavirus Pandemic Chief Editor: Dr. Chen Xin CHINA-CEE INSTITUTE Budapest, October 2020 Content Preface ............................................................................................................ 5 Part I POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT OUTLOOK ..................................... 7 Albanian politics in post-pandemic era: reshuffling influence and preparing for the next elections .............................................................................................. 8 BiH political outlook after the COVID-19 pandemic ...................................... 13 Bulgarian Political Development Outlook in Post-Pandemic Era ..................... 18 Forecast of Croatian Political Events after the COVID-19 .............................. 25 Czech Political Outlook for the Post-Crisis Period .......................................... 30 Estonian political outlook after the pandemic: Are we there yet? ................... -

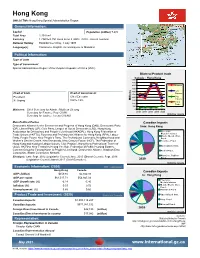

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information: Capital Population (million) 7.474n/a Total Area 1,104 km² Currency 1 CAN$=5.791 Hong Kong $ (HKD) (2020 - Annual average) National Holiday Establishment Day, 1 July 1997 Language(s) Cantonese, English, increasing use of Mandarin Political Information: Type of State Type of Government Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Bilateral Product trade Canada - Hong Kong 5000 4500 4000 Balance 3500 3000 Can. Head of State Head of Government Exports 2500 President Chief Executive 2000 Can. Imports XI Jinping Carrie Lam Millions 1500 Total 1000 Trade 500 Ministers: Chief Secretary for Admin.: Matthew Cheung 0 Secretary for Finance: Paul CHAN 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Statistics Canada Secretary for Justice: Teresa CHENG Main Political Parties Canadian Imports Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB), Democratic Party from: Hong Kong (DP), Liberal Party (LP), Civic Party, League of Social Democrats (LSD), Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood (HKADPL), Hong Kong Federation of Precio us M etals/ stones Trade Unions (HKFTU), Business and Professionals Alliance for Hong Kong (BPA), Labour M ach. M ech. Elec. Party, People Power, New People’s Party, The Professional Commons, Neighbourhood and Prod. Worker’s Service Centre, Neo Democrats, New Century Forum (NCF), The Federation of Textiles Prod. Hong Kong and Kowloon Labour Unions, Civic Passion, Hong Kong Professional Teachers' Union, HK First, New Territories Heung Yee Kuk, Federation of Public Housing Estates, Specialized Inst. Concern Group for Tseung Kwan O People's Livelihood, Democratic Alliance, Kowloon East Food Prod. -

Download/Print the Study in PDF Format

GENERAL ELECTIONS IN ARMENIA 6th May 2012 European Elections monitor Republican Party led by the President of the Republic Serzh Sarkisian is the main favourite in Corinne Deloy the general elections in Armenia. On 23rd February last the Armenian authorities announced that the next general elections would Analysis take place on 6th May. Nine political parties are running: the five parties represented in the Natio- 1 month before nal Assembly, the only chamber in parliament comprising the Republican Party of Armenia (HHK), the poll Prosperous Armenia (BHK), the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (HHD), Rule of Law (Orinats Erkir, OEK) and Heritage (Z), which is standing in a coalition with the Free Democrats of Khachatur Kokobelian, as well as the Armenian National Congress (HAK), the Communist Party (HKK), the Democratic Party and the United Armenians. The Armenian government led by Prime Minister Tigran Sarkisian (HHK) has comprised the Republi- can Party, Prosperous Armenia and Rule of Law since 21st March 2008. The Armenian Revolutionary Federation was a member of the government coalition until 2009 before leaving it because of its opposition to the government’s foreign policy. On 12th February last the Armenians elected their local representatives. The Republican Party led by President of the Republic Serzh Sarkisian won 33 of the 39 country’s towns. The opposition clai- med that there had been electoral fraud. The legislative campaign started on 8th April and will end on 4th May. 238 people working in Arme- nia’s embassies or consulates will be able to vote on 27th April and 1st May. The parties running Prosperous Armenia leader, Gagik Tsarukian will lead his The Republican Party will be led by the President of the party’s list. -

OSCE .Armenia Parliamentary Elections Preliminary Statement.Pdf

OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights Election Observation Mission Republic of Armenia Parliamentary Elections, 6 May 2012 INTERIM REPORT No. 2 3 - 24 April 2012 27 April 2012 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • The election campaign, which officially started on 8 April, is vibrant. Contestants are generally able to campaign and have been provided with free venues and poster space. However, there have been instances of obstruction of campaign activities, including two violent scuffles in Yerevan. • The OSCE/ODIHR Election Observation Mission (EOM) has noted cases where campaign provisions of the Electoral Code were violated. These included campaigning in schools, teachers and students being asked to attend campaign events of the Republican Party of Armenia, and campaign material of some parties being placed on municipal buildings and polling stations. A business owned by the leader of Prosperous Armenia is distributing tractors in several provinces, de facto as part of the party’s campaign. As of 17 April, the police has examined or was examining 14 cases of possible electoral offences. • Preparations for the elections are proceeding according to legal deadlines. The Central Election Commission (CEC) and Territorial Election Commissions (TECs) continue to work in an open and transparent manner. Precinct Election Commissions (PECs) have been formed and are being trained. The CEC has adopted and published the main procedural rules and official documents, well in advance of election day. • The media monitored by the OSCE/ODIHR EOM are providing extensive political and election-related coverage. Before the start of the official campaign, the President and government officials received extensive coverage in the monitored media. -

The Basic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong, 3 Loy

Loyola University Chicago International Law Review Volume 3 Article 5 Issue 2 Spring/Summer 2006 2006 The aB sic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong Michael C. Davis Chinese University of Hong Kong Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael C. Davis The Basic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong, 3 Loy. U. Chi. Int'l L. Rev. 165 (2006). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr/vol3/iss2/5 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago International Law Review by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BASIC LAW AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN HONG KONG Michael C. Davist I. Introduction Hong Kong's status as a Special Administrative Region of China has placed it on the foreign policy radar of most countries having relations with China and interests in Asia. This interest in Hong Kong has encouraged considerable inter- est in Hong Kong's founding documents and their interpretation. Hong Kong's constitution, the Hong Kong Basic Law ("Basic Law"), has sparked a number of debates over democratization and its pace. It is generally understood that greater democratization will mean greater autonomy and vice versa, less democracy means more control by Beijing. For this reason there is considerable interest in the politics of interpreting Hong Kong's Basic Law across the political spectrum in Hong Kong, in Beijing and in many foreign capitals. -

Document Country: Macedonia Lfes ID: Rol727

Date Printed: 11/06/2008 JTS Box Number: lFES 7 Tab Number: 5 Document Title: Macedonia Final Report, May 2000-March 2002 Document Date: 2002 Document Country: Macedonia lFES ID: ROl727 I I I I I I I I I IFES MISSION STATEMENT I I The purpose of IFES is to provide technical assistance in the promotion of democracy worldwide and to serve as a clearinghouse for information about I democratic development and elections. IFES is dedicated to the success of democracy throughout the world, believing that it is the preferred form of gov I ernment. At the same time, IFES firmly believes that each nation requesting assistance must take into consideration its unique social, cultural, and envi I ronmental influences. The Foundation recognizes that democracy is a dynam ic process with no single blueprint. IFES is nonpartisan, multinational, and inter I disciplinary in its approach. I I I I MAKING DEMOCRACY WORK Macedonia FINAL REPORT May 2000- March 2002 USAID COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT No. EE-A-00-97-00034-00 Submitted to the UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT by the INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR ELECTION SYSTEMS I I TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTNE SUMMARY I I. PROGRAMMATIC ACTNITIES ............................................................................................. 1 A. 2000 Pre Election Technical Assessment 1 I. Background ................................................................................. 1 I 2. Objectives ................................................................................... 1 3. Scope of Mission .........................................................................2 -

Between Denial and "Comparative Trivialization": Holocaust Negationism in Post-Communist East Central Europe

Between Denial and "Comparative Trivialization": Holocaust Negationism in Post-Communist East Central Europe Michael Shafir Motto: They used to pour millet on graves or poppy seeds To feed the dead who would come disguised as birds. I put this book here for you, who once lived So that you should visit us no more Czeslaw Milosz Introduction* Holocaust denial in post-Communist East Central Europe is a fact. And, like most facts, its shades are many. Sometimes, denial comes in explicit forms – visible and universally-aggressive. At other times, however, it is implicit rather than explicit, particularistic rather than universal, defensive rather than aggressive. And between these two poles, the spectrum is large enough to allow for a large variety of forms, some of which may escape the eye of all but the most versatile connoisseurs of country-specific history, culture, or immediate political environment. In other words, Holocaust denial in the region ranges from sheer emulation of negationism elsewhere in the world to regional-specific forms of collective defense of national "historic memory" and to merely banal, indeed sometime cynical, attempts at the utilitarian exploitation of an immediate political context.1 The paradox of Holocaust negation in East Central Europe is that, alas, this is neither "good" nor "bad" for the Jews.2 But it is an important part of the * I would like to acknowledge the support of the J. and O. Winter Fund of the Graduate Center of the City University of New York for research conducted in connection with this project. I am indebted to friends and colleagues who read manuscripts of earlier versions and provided comments and corrections. -

A Canadian Model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A

Proportional-first-past-the-post: A Canadian model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Memorial University St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador May 2014 ii Abstract For more than a decade a majority of Canadians have consistently supported the idea of proportional representation when asked, yet all attempts at electoral reform thus far have failed. Even though a majority of Canadians support proportional representation, a majority also report they are satisfied with the current electoral system (even indicating support for both in the same survey). The author seeks to reconcile these potentially conflicting desires by designing a uniquely Canadian electoral system that keeps the positive and familiar features of first-past-the- post while creating a proportional election result. The author touches on the theory of representative democracy and its relationship with proportional representation before delving into the mechanics of electoral systems. He surveys some of the major electoral system proposals and options for Canada before finally presenting his made-in-Canada solution that he believes stands a better chance at gaining approval from Canadians than past proposals. iii Acknowledgements First of foremost, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my brilliant supervisor, Dr. Amanda Bittner, whose continuous guidance, support, and advice over the past few years has been invaluable. I am especially grateful to you for encouraging me to pursue my Master’s and write about my electoral system idea. -

Declining Support for Government of Donald Tusk and for Civic Platform (Po)

DECLINING SUPPORT FOR GOVERNMENT OF DONALD TUSK AND FOR CIVIC PLATFORM (PO) The coalition of Civic Platform and Polish Peasant Party (PO-PSL), which has governed Poland for over four years, is losing social support. Evaluations of the government of Donald Tusk have deteriorated. At present, they are the worst, if both parliamentary terms are considered. The decline was precipitated by, among others, problems with implementation of new rules on refunding medicines, signing of the ACTA agreement (a decision from which the government eventually withdrew), and planned changes in the pension system, especially raising the retirement age to 67 years. From Dec. 2011 to March 2012 the proportion of government supporters fell from 44% to 31%, while the number of opponents rose from 31% to 45%. ATTITUDE TO THE GOVERNMENT OF DONALD TUSK “Don't know” omitted The popularity of the Prime Minster is diminishing. The proportion of respondents satisfied with the work of Donald Tusk as Prime Minister fell from 49% in Dec. 2011 to 33% in March 2012. At the same time, the number of the dissatisfied rose from 38% to 57%. SATISFACTION WITH DONALD TUSK AS PRIME MINISTER “Don't know” omitted The effects of government's activities are perceived ever more critically. The proportion of people satisfied with them fell in the last four months from 45% to 25%, while the number of the dissatisfied rose from 40% to 67%. EVALUATION OF EFFECTS OF ACTIVITY OF DONALD TUSK'S GOVERNMENT UP TO DATE “Don't know” omitted The decline in support for the government is accompanied by a drop in the ratings of the Civic Platform (PO). -

Codebook Indiveu – Party Preferences

Codebook InDivEU – party preferences European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies December 2020 Introduction The “InDivEU – party preferences” dataset provides data on the positions of more than 400 parties from 28 countries1 on questions of (differentiated) European integration. The dataset comprises a selection of party positions taken from two existing datasets: (1) The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File contains party positions for three rounds of European Parliament elections (2009, 2014, and 2019). Party positions were determined in an iterative process of party self-placement and expert judgement. For more information: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/65944 (2) The Chapel Hill Expert Survey The Chapel Hill Expert Survey contains party positions for the national elections most closely corresponding the European Parliament elections of 2009, 2014, 2019. Party positions were determined by expert judgement. For more information: https://www.chesdata.eu/ Three additional party positions, related to DI-specific questions, are included in the dataset. These positions were determined by experts involved in the 2019 edition of euandi after the elections took place. The inclusion of party positions in the “InDivEU – party preferences” is limited to the following issues: - General questions about the EU - Questions about EU policy - Questions about differentiated integration - Questions about party ideology 1 This includes all 27 member states of the European Union in 2020, plus the United Kingdom. How to Cite When using the ‘InDivEU – Party Preferences’ dataset, please cite all of the following three articles: 1. Reiljan, Andres, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, Lorenzo Cicchi, Diego Garzia, Alexander H.