The Extreme Right in Contemporary Romania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romanian Political Science Review Vol. XXI, No. 1 2021

Romanian Political Science Review vol. XXI, no. 1 2021 The end of the Cold War, and the extinction of communism both as an ideology and a practice of government, not only have made possible an unparalleled experiment in building a democratic order in Central and Eastern Europe, but have opened up a most extraordinary intellectual opportunity: to understand, compare and eventually appraise what had previously been neither understandable nor comparable. Studia Politica. Romanian Political Science Review was established in the realization that the problems and concerns of both new and old democracies are beginning to converge. The journal fosters the work of the first generations of Romanian political scientists permeated by a sense of critical engagement with European and American intellectual and political traditions that inspired and explained the modern notions of democracy, pluralism, political liberty, individual freedom, and civil rights. Believing that ideas do matter, the Editors share a common commitment as intellectuals and scholars to try to shed light on the major political problems facing Romania, a country that has recently undergone unprecedented political and social changes. They think of Studia Politica. Romanian Political Science Review as a challenge and a mandate to be involved in scholarly issues of fundamental importance, related not only to the democratization of Romanian polity and politics, to the “great transformation” that is taking place in Central and Eastern Europe, but also to the make-over of the assumptions and prospects of their discipline. They hope to be joined in by those scholars in other countries who feel that the demise of communism calls for a new political science able to reassess the very foundations of democratic ideals and procedures. -

CONSTITUȚIE*) Din 21 Noiembrie 1991 (*Republicată*) EMITENT PARLAMENTUL Publicat În MONITORUL OFICIAL Nr

CONSTITUȚIE*) din 21 noiembrie 1991 (*republicată*) EMITENT PARLAMENTUL Publicat în MONITORUL OFICIAL nr. 767 din 31 octombrie 2003 Notă *) Modificată și completată prin Legea de revizuire a Constituției României nr. 429/2003, publicată în Monitorul Oficial al României, Partea I, nr. 758 din 29 octombrie 2003, republicată de Consiliul Legislativ, în temeiul art. 152 din Constituție, cu reactualizarea denumirilor și dându-se textelor o noua numerotare (art. 152 a devenit, în forma republicată, art. 156). Legea de revizuire a Constituției României nr. 429/2003 a fost aprobată prin referendumul național din 18-19 octombrie 2003 și a intrat în vigoare la data de 29 octombrie 2003, data publicării în Monitorul Oficial al României, Partea I, nr. 758 din 29 octombrie 2003 a Hotărârii Curții Constituționale nr. 3 din 22 octombrie 2003 pentru confirmarea rezultatului referendumului național din 18-19 octombrie 2003 privind Legea de revizuire a Constituției României. Constituția României, în forma inițială, a fost adoptată în ședința Adunării Constituante din 21 noiembrie 1991, a fost publicată în Monitorul Oficial al României, Partea I, nr. 233 din 21 noiembrie 1991 și a intrat în vigoare în urma aprobării ei prin referendumul național din 8 decembrie 1991. Titlul I Principii generale Articolul 1 Statul român (1) România este stat național, suveran și independent, unitar și indivizibil. (2) Forma de guvernamant a statului român este republica. (3) România este stat de drept, democratic și social, în care demnitatea omului, drepturile și libertățile cetățenilor, libera dezvoltare a personalității umane, dreptatea și pluralismul politic reprezintă valori supreme, în spiritul traditiilor democratice ale poporului român și idealurilor Revoluției din decembrie 1989, și sunt garantate. -

“Romanian Football Federation: in Search of Good Governance”

“Romanian Football Federation: in search of good governance” Florian Petrică Play The Game 2017 Eindhoven, November 29 LPF vs FRF Control over the national team and distribution of TV money Gigi Becali, FCSB owner (former Razvan Burleanu, FRF president Steaua) “The future is important now. Burleanu is - under his mandate, the Romanian national a problem, he should go, it is necessary team was led for the first time by a foreign to combine the sports, journalistic and coach – the German Christoph Daum political forces to get him down. National forces must also be involved to take him - has attracted criticism from club owners after down" Gigi Becali proposing LPF to cede 5% of TV rights revenue to lower leagues. Romanian teams in international competitions The National Team World Cup 1994, SUA: the 6th place 1998, France: latest qualification FIFA ranking: 3-rd place, 1997 The European Championship 2000, Belgium - Netherlands: the 7-th place National was ranked 7th 2016: latest qualification (last place in Group A, no win) FIFA ranking: 41-st place, 2017 The Romanian clubs 2006: Steaua vs Rapid in the quarterfinals of the UEFA Cup. Steaua lost the semi-final with Middlesbrough (2-4) ROMANIA. THE MOST IMPORTANT FOOTBALL TRANSFERS. 1990-2009 No Player Club Destination Value (dollars) Year 1. Mirel Rădoi Steaua Al Hilal 7.700.000 2009 2. Ionuţ Mazilu Rapid Dnepr 5.200.000 2008 3. Gheorghe Hagi Steaua Real Madrid 4.300.000 1990 4. George Ogararu Steaua Ajax 4.000.000 2006 5. Adrian Ropotan Dinamo Dinamo Moscova 3.900.000 2009 6. -

Archives and Human Rights

12 Truth, memory, and reconciliation in post- communist societies The Romanian experience and the Securitate archives Marius Stan and Vladimir Tismaneanu Introduction Coming to terms with the past, confronting its legacies and burden, was the inevitable starting point for the new democracies of Eastern Europe. Thirty years after the fall of communism, both public intellectuals and scholars face a fundamental question: how can truth and justice be rein- stated in a post-totalitarian community without the emergence of what Nietzsche called the “reek of cruelty”? In 2006, for the first time in Roma- nia’s contemporary history, the Presidential Commission for the Analysis of the Communist Dictatorship in Romania (PCACDR) rejected outright the practices of institutionalized forgetfulness and generated a national debate about long-denied and concealed moments of the communist past (includ- ing instances of collaboration, complicity, etc.). One of these authors (VT) had the honor of being appointed Chair of this state-body. He was one of the co- coordinators of its Final Report.1 Generally speaking, decommuni- zation is, in its essence, a moral, political, and intellectual process.2 The PCACDR Report answered a fundamental necessity, characteristic of the post-authoritarian world, that of moral clarity. Only memory and history can furnish responsibility, justice, retribution, and repentance. Reconcilia- tion and the healing of a nation plagued by the traumatic quagmire of Evil depend on the recognition and non-negotiability of human dignity as a pri- mordial moral truth of the new society. Context In January 2007, Romania acceded to the European Union, a few years after having entered the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). -

Football and Romanian Masculinity. How It Is Constructed by the Sport Media?

STUDIA UBB SOCIOLOGIA, 62 (LXII), 2, 2017, pp. 79-97 DOI: 10.1515/subbs-2017-0012 FOOTBALL AND ROMANIAN MASCULINITY. HOW IT IS CONSTRUCTED BY THE SPORT MEDIA? LÁSZLÓ PÉTER1 ABSTRACT. The present article is focusing on hegemonic masculinity represented and expressed by the professional footballers. Based on the empirical study using text analysis of leading articles published in central Romanian sport newspapers I draw the ideal-typical picture of the normative model of Romanian hegemonic masculinity in which the domestic coaches play a determinant role. Their personal-individual and collective-professional features like determination, steadiness, honesty, pride, mutual respect, knowledge, tenaciousness, sense of vocation, solidarity, spirit of fighting are the corner points of the constructed Romanian manhood, or hegemonic masculinity during social change. The manliness is traced along the inner characteristic of the coaches but in strong contradiction with the foreign trainers. In this respect I can state that football is connected not only with masculinity but in some respect also with the national characteristics embodied by the Romanian coaches especially those working home. Keywords: football, hegemonic masculinity, media, discourses Introduction Football and masculinity had been connected: ball games were played by men as early as in the antiquity and in the Middle Ages. It can be assumed that the “game”, often leading to fights, hitting and affray, provided an opportunity to men to express and show their physical strength, resolution and masculine qualities to the women of the community. Playing ball games meant public/ community events, during which participant men could leave the monotonous routine of everyday life behind and could show off their masculine features to their audience.2 Team sports represent socializing frames in which competing or contesting men acquire and express the institutional and organized standards of their masculinity (Anderson, 2008). -

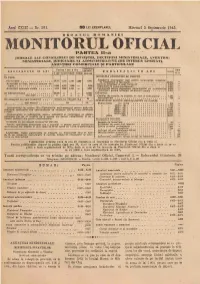

Monitorul Oficial Dill a Dotta Zi

Anul CXIII Nr. 201. 00 LEI EXEMPLARUL illiereurl 5 Septemvrie 1945. 11. REUATHL ROMANIEI MONITORULPARTEA ElaL OFICIAL JURNALE .ALE CONSILIULUI DE MINISTRI, DECIZIUNI MINISTERIALE, ANUNTUR1 MINISTERIALE, JUDICIARE SI ADMINISTRATIVE (DE INTERES LIMITAT), ANUNTURI COMERCIALE SI PARTICULARE 101form. flesbatarile Partea I sari a II-a LINIA ABONAMENTE IN LEI parlament. PUBLICATII IN LE/ laser* 0. ..... 1 anIsIunhI3IunhIlIunäl sesiune IN TARA: JURNALELE CONSILIULUI DE MINISTRI Particulari 10 0005.000 2.500 1.200 6.000 Acordarea avantajelor legii pentru incurajarea industriei la industriasii fabricanti 20.000 Autoritati de Stat, judet si comune ur- Idem la meseriasi si mori tam-most! 4.030 bane 8.000 4.000 2.000 MOO 6.000 Schimbäri de nume, incetäteniri 8 000 .Autorltitti comunale rurale 4.000 2.000 1.000 6.090 Conannicate pentru depunerea juritmfintului de incetatenire8.000 AutorizAri pentru inflintari de birouri vamale ....... 5.000 IN STRAINATATE I 25.000 . 1 12.000 CITATIILE: tine lunri am= mf On. 2.500 Curtilor de Casatle, de Conturi, de Apeii tribunalelor 1.500 Judedttoriilor 750 50 part. I-a60 part. ll-a so Un exemplar din anul curent loi PUBLICATIILE PENTRU AMENAJAMENTE DE PADURI: too ff es anti trecuti Ptiduri intro 0 10 ha 800 PM... 20 1 900 Abonarnentul la partea Ill-a (Desbaterile parlamentare) pentru sesitmile If « 20,01 100 2 500 Ordinare, prelttngite sau extraordinaro se socoteste 1.200 lei lunar (minimum 100,01 200 10 000 I lunä). 200,01 509 15.000 Abonamentele si 131:Mica-title, pentru autoritAtl siparticulari se platesc 7, 500,01-1000 25.000 anticipat. Ele vor fiInsotite de o adresti din partea autoritritilor si de o peste 1009 30 000 cerere timbratil din partea particularilor. -

European Influences in Moldova Page 2

Master Thesis Human Geography Name : Marieke van Seeters Specialization : Europe; Borders, Governance and Identities University : Radboud University, Nijmegen Supervisor : Dr. M.M.E.M. Rutten Date : March 2010, Nijmegen Marieke van Seeters European influences in Moldova Page 2 Summary The past decades the European continent faced several major changes. Geographical changes but also political, economical and social-cultural shifts. One of the most debated topics is the European Union and its impact on and outside the continent. This thesis is about the external influence of the EU, on one of the countries which borders the EU directly; Moldova. Before its independency from the Soviet Union in 1991, it never existed as a sovereign state. Moldova was one of the countries which were carved out of history by the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact in 1940 as it became a Soviet State. The Soviet ideology was based on the creation of a separate Moldovan republic formed by an artificial Moldovan nation. Although the territory of the Moldovan Soviet Socialist Republic was a former part of the Romanian province Bessarabia, the Soviets emphasized the unique and distinct culture of the Moldovans. To underline this uniqueness they changed the Moldovan writing from Latin to Cyrillic to make Moldovans more distinct from Romanians. When Moldova became independent in 1991, the country struggled with questions about its national identity, including its continued existence as a separate nation. In the 1990s some Moldovan politicians focussed on the option of reintegration in a Greater Romania. However this did not work out as expected, or at least hoped for, because the many years under Soviet rule and delinkage from Romania had changed Moldovan society deeply. -

Communism and Post-Communism in Romania : Challenges to Democratic Transition

TITLE : COMMUNISM AND POST-COMMUNISM IN ROMANIA : CHALLENGES TO DEMOCRATIC TRANSITION AUTHOR : VLADIMIR TISMANEANU, University of Marylan d THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FO R EURASIAN AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE VIII PROGRA M 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N .W . Washington, D .C . 20036 LEGAL NOTICE The Government of the District of Columbia has certified an amendment of th e Articles of Incorporation of the National Council for Soviet and East European Research changing the name of the Corporation to THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR EURASIAN AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARCH, effective on June 9, 1997. Grants, contracts and all other legal engagements of and with the Corporation made unde r its former name are unaffected and remain in force unless/until modified in writin g by the parties thereto . PROJECT INFORMATION : 1 CONTRACTOR : University of Marylan d PR1NCIPAL 1NVEST1GATOR : Vladimir Tismanean u COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 81 1-2 3 DATE : March 26, 1998 COPYRIGHT INFORMATIO N Individual researchers retain the copyright on their work products derived from research funded by contract with the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research . However, the Council and the United States Government have the right to duplicate an d disseminate, in written and electronic form, this Report submitted to the Council under thi s Contract, as follows : Such dissemination may be made by the Council solely (a) for its ow n internal use, and (b) to the United States Government (1) for its own internal use ; (2) for further dissemination to domestic, international and foreign governments, entities an d individuals to serve official United States Government purposes ; and (3) for dissemination i n accordance with the Freedom of Information Act or other law or policy of the United State s Government granting the public rights of access to documents held by the United State s Government. -

Marius Lăcătuș

959.168 DE VIZITATORI unici lunar pe www.prosport.ro (SATI) • 619.000 CITITORI zilnic (SNA octombrie 2007 - octombrie 2008) Numărul 3600 Marți, 21 aprilie 2009 24 pagini Tiraj: 110.000 AZI AI BANI, MAȘINI ȘI CUPOANE DE PARIURI ÎN ZIAR »17 ATENȚIE!!! VALIZA CU BANI Cotidian național de sport editat de Publimedia Internațional - Companie MediaPro EDIȚIE NAȚIONALĂ de AZI AI TALON! GHEORGHIU Unii conducători de club GHEORGHIU află prin intermediul LIGA LUI MITICĂ, INTERMEDIAR LPF cine îi arbitrează BOZOVIC, TURIST cu mult înaintea ÎNTRE CLUBURI ŞI ARBITRI! anunului oficial »14 LA RAPID Muntenegreanul evacuat din casă speră să devină liber România pentru că nu avea viză de DIALOG DE TAINĂ ÎNTRE PATRON, ANTRENOR muncă, ci de turist »8-9 ŞI JUCĂTORI ÎN VESTIARUL STELEI de NEGOESCU ZOOM: Gheorghiu explică de MARIAN »2-5 de ce l-a bătut Rapid pe Foto: Alexandru HOJDA Lucescu jr »18 VORBELE ETAPEI: Caramavrov şi Geantă despre eliberarea Stelei »19 SPECIAL Mircea Rednic pare că se ghidea- ză la Dinamo după deviza „antrena- mentele lungi şi dese, cheia marilor succese“ GIGI BECALI: »6-7 DOAR Cel mai bun ziar de sport din din sport de ziar bun mai Cel O ZI LIBERĂ ro „Vreau titlul!“ ÎN DOUĂ MARIUS LĂCĂTUȘ: SĂPTĂMÂNI! de PITARU N-AM FOST LA EURO PENTRU CĂ AVEAM „i-l iau!“ MÂNECI SCURTE! Lubos Michel a mai găsit o • Becali îl împinge pe Dayro înapoi între titulari! • Ghionea a aflat ieri scuză pentru greşeala care că mâine e suspendat! • Steaua – CFR, în premieră fără prime • Clujenii ne-a lăsat acasă la Euro www.prosport. -

Between Denial and "Comparative Trivialization": Holocaust Negationism in Post-Communist East Central Europe

Between Denial and "Comparative Trivialization": Holocaust Negationism in Post-Communist East Central Europe Michael Shafir Motto: They used to pour millet on graves or poppy seeds To feed the dead who would come disguised as birds. I put this book here for you, who once lived So that you should visit us no more Czeslaw Milosz Introduction* Holocaust denial in post-Communist East Central Europe is a fact. And, like most facts, its shades are many. Sometimes, denial comes in explicit forms – visible and universally-aggressive. At other times, however, it is implicit rather than explicit, particularistic rather than universal, defensive rather than aggressive. And between these two poles, the spectrum is large enough to allow for a large variety of forms, some of which may escape the eye of all but the most versatile connoisseurs of country-specific history, culture, or immediate political environment. In other words, Holocaust denial in the region ranges from sheer emulation of negationism elsewhere in the world to regional-specific forms of collective defense of national "historic memory" and to merely banal, indeed sometime cynical, attempts at the utilitarian exploitation of an immediate political context.1 The paradox of Holocaust negation in East Central Europe is that, alas, this is neither "good" nor "bad" for the Jews.2 But it is an important part of the * I would like to acknowledge the support of the J. and O. Winter Fund of the Graduate Center of the City University of New York for research conducted in connection with this project. I am indebted to friends and colleagues who read manuscripts of earlier versions and provided comments and corrections. -

Codebook Indiveu – Party Preferences

Codebook InDivEU – party preferences European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies December 2020 Introduction The “InDivEU – party preferences” dataset provides data on the positions of more than 400 parties from 28 countries1 on questions of (differentiated) European integration. The dataset comprises a selection of party positions taken from two existing datasets: (1) The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File contains party positions for three rounds of European Parliament elections (2009, 2014, and 2019). Party positions were determined in an iterative process of party self-placement and expert judgement. For more information: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/65944 (2) The Chapel Hill Expert Survey The Chapel Hill Expert Survey contains party positions for the national elections most closely corresponding the European Parliament elections of 2009, 2014, 2019. Party positions were determined by expert judgement. For more information: https://www.chesdata.eu/ Three additional party positions, related to DI-specific questions, are included in the dataset. These positions were determined by experts involved in the 2019 edition of euandi after the elections took place. The inclusion of party positions in the “InDivEU – party preferences” is limited to the following issues: - General questions about the EU - Questions about EU policy - Questions about differentiated integration - Questions about party ideology 1 This includes all 27 member states of the European Union in 2020, plus the United Kingdom. How to Cite When using the ‘InDivEU – Party Preferences’ dataset, please cite all of the following three articles: 1. Reiljan, Andres, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, Lorenzo Cicchi, Diego Garzia, Alexander H. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions.