Document Country: Macedonia Lfes ID: Rol727

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Canadian Model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A

Proportional-first-past-the-post: A Canadian model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Memorial University St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador May 2014 ii Abstract For more than a decade a majority of Canadians have consistently supported the idea of proportional representation when asked, yet all attempts at electoral reform thus far have failed. Even though a majority of Canadians support proportional representation, a majority also report they are satisfied with the current electoral system (even indicating support for both in the same survey). The author seeks to reconcile these potentially conflicting desires by designing a uniquely Canadian electoral system that keeps the positive and familiar features of first-past-the- post while creating a proportional election result. The author touches on the theory of representative democracy and its relationship with proportional representation before delving into the mechanics of electoral systems. He surveys some of the major electoral system proposals and options for Canada before finally presenting his made-in-Canada solution that he believes stands a better chance at gaining approval from Canadians than past proposals. iii Acknowledgements First of foremost, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my brilliant supervisor, Dr. Amanda Bittner, whose continuous guidance, support, and advice over the past few years has been invaluable. I am especially grateful to you for encouraging me to pursue my Master’s and write about my electoral system idea. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Another Consideration in Minority Vote Dilution Remedies: Rent

Another C onsideration in Minority Vote Dilution Remedies : Rent -Seeking ALAN LOCKARD St. Lawrence University In some areas of the United States, racial and ethnic minorities have been effectively excluded from the democratic process by a variety of means, including electoral laws. In some instances, the Courts have sought to remedy this problem by imposing alternative voting methods, such as cumulative voting. I examine several voting methods with regard to their sensitivity to rent-seeking. Methods which are less sensitive to rent-seeking are preferred because they involve less social waste, and are less likely to be co- opted by special interest groups. I find that proportional representation methods, rather than semi- proportional ones, such as cumulative voting, are relatively insensitive to rent-seeking efforts, and thus preferable. I also suggest that an even less sensitive method, the proportional lottery, may be appropriate for use within deliberative bodies, where proportional representation is inapplicable and minority vote dilution otherwise remains an intractable problem. 1. INTRODUCTION When President Clinton nominated Lani Guinier to serve in the Justice Department as Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights, an opportunity was created for an extremely valuable public debate on the merits of alternative voting methods as solutions to vote dilution problems in the United States. After Prof. Guinier’s positions were grossly mischaracterized in the press,1 the President withdrew her nomination without permitting such a public debate to take place.2 These issues have been discussed in academic circles,3 however, 1 Bolick (1993) charges Guinier with advocating “a complex racial spoils system.” 2 Guinier (1998) recounts her experiences in this process. -

Electoral Reform Three Case Studies

Electoral reform Three Case Studies • Japan • New Zealand • Italy MMM vs. MMP • MMM vs. MMP… what’s the difference? • In both, seats are allocated at the district and national levels • MMP is a hybrid system – District-level winners – National PR is compensatory • MMM is a parallel voting system – List seats allocated proportionally… – …But not linked to district-level winners • What are plusses and minuses? Why do political scientists like MMP better? Electoral reform: Japan (1996) • BEFORE: SNTV – What kinds of problems did SNTV bring? • AFTER: MMM • WHY: LDP wanted reform. Electoral reform: Japan • In 1970, PM Satō asked a party committee to propose an electoral system based on single-seat districts to “produce party-centered, policy-centered campaigns.” Effect of electoral reform: Indices Year D (LSq) N(v) N(s) S 6.20 3.82 3.08 12.28 3.66 2.60 Period averages in red (overall in post-reform period through 2009) 6 2009 Election Results Electoral reform: New Zealand (1996) • BEFORE: FPTP • AFTER: MMP • WHY: It’s complicated! New Zealand: Problems with the old system 9 An electoral system working “too well” New Zealand is classic case of an electoral system producing too much majoritarianism New Zealand Electoral Statistics, 1978-1993 Party 1978 1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 Labour Vote % 40.4 39.0 43.0 48.0 35.1 34.7 Seat % 43.5 46.7 60.0 58.8 29.9 45.5 National Vote % 39.8 38.8 35.9 44.0 47.8 35.0 Seat % 55.4 51.1 37.9 41.2 69.1 50.5 Social Credit Vote % 16.1 20.7 7.6 - - - Seat % 1.1 2.2 2.1 - - - NZ Party Vote % - - 12.3 0.3 - - Seat % - - 0.0 0.0 - - *Alliance Vote % - - - - 14.3 18.2 Seat % - - - - 1.0 2.0 NZ First Vote % - - - - - 8.4 Seat % - - - - - 0.0 *The Alliance consists of several minor third parties, including Green, New Labour, Democrat and Mana Motuhake. -

![Arxiv:2105.00216V1 [Cs.MA] 1 May 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2651/arxiv-2105-00216v1-cs-ma-1-may-2021-942651.webp)

Arxiv:2105.00216V1 [Cs.MA] 1 May 2021

Lecture Notes on Voting Theory Davide Grossi Bernoulli Institute for Maths, CS and AI University of Groningen Amsterdam Center for Law and Economics Institute for Logic, Language and Computation University of Amsterdam www.davidegrossi.me ©Davide Grossi 2021 arXiv:2105.00216v1 [cs.MA] 1 May 2021 Contents 1 Choosing One Out of Two 2 1.1 Preliminaries ................................... ........ 2 1.1.1 Keydefinitions ................................. ..... 2 1.1.2 Basicaxioms ................................... .... 3 1.2 Plurality is the best . when m =2 .............................. 5 1.2.1 Axiomatic characterizations of plurality when m =2................. 6 1.2.2 Plurality as maximum likelihood estimator when m =2 ............... 7 1.3 Chapternotes.................................... ....... 10 1.4 Exercises ....................................... ...... 10 2 Choosing One Out of Many 11 2.1 Beyondplurality ................................. ........ 11 2.1.1 Plurality selects unpopular options . ............. 11 2.1.2 Morevotingrules............................... ...... 12 2.1.3 MoreaxiomsforSCFs ............................. ..... 16 2.1.4 Impossibility results for SCFs: examples . .............. 17 2.2 There is no obvious social choice function when m> 2.................... 17 2.2.1 Socialpreferencefunctions. ........... 17 2.2.2 Arrow’stheorem ................................ ..... 18 2.3 Social choice by maximum likelihood & closest consensus .................. 21 2.3.1 The Condorcet model when m> 2........................... 21 -

EU Electoral Law Memorandum.Pages

Memorandum on the Electoral Law of the European Union: Confederal and Federal Legitimacy and Turnout European Parliament Committee on Constitutional Affairs Hearing on Electoral Reform Brendan O’Leary, BA (Oxon), PhD (LSE) Lauder Professor of Political Science, University of Pennsylvania Citizen of Ireland and Citizen of the USA1 submitted November 26 2014 hearing December 3 2014 Page !1 of !22 The European Parliament, on one view, is a direct descendant of its confederal precursor, which was indirectly elected from among the member-state parliaments of the ESCC and the EEC. In a very different view the Parliament is the incipient first chamber of the European federal demos, an integral component of a European federation in the making.2 These contrasting confederal and federal understandings imply very different approaches to the law(s) regulating the election of the European Parliament. 1. The Confederal Understanding In the confederal vision of Europe as a union of sovereign member-states, each member- state should pass its own electoral laws, execute its own electoral administration, and regulate the conduct of its representatives in European institutions, who should be accountable to member- state parties and citizens, and indeed function as their “mandatable” delegates. In the strongest confederal vision, in the conduct of EU law-making and policy MEPs should have less powers and status than the ministers of member-states, and their delegated authorities (e.g., ambassadors, or functionally specialized civil servants). In most confederal visions MEPs should be indirectly elected from and accountable to their home parliaments. Applied astringently, the confederal understanding would suggest that the current Parliament has been mis-designed, and operating beyond its appropriate functions at least since 1979. -

The Expanding Approvals Rule: Improving Proportional Representation and Monotonicity 3

Working Paper The Expanding Approvals Rule: Improving Proportional Representation and Monotonicity Haris Aziz · Barton E. Lee Abstract Proportional representation (PR) is often discussed in voting settings as a major desideratum. For the past century or so, it is common both in practice and in the academic literature to jump to single transferable vote (STV) as the solution for achieving PR. Some of the most prominent electoral reform movements around the globe are pushing for the adoption of STV. It has been termed a major open prob- lem to design a voting rule that satisfies the same PR properties as STV and better monotonicity properties. In this paper, we first present a taxonomy of proportional representation axioms for general weak order preferences, some of which generalise and strengthen previously introduced concepts. We then present a rule called Expand- ing Approvals Rule (EAR) that satisfies properties stronger than the central PR axiom satisfied by STV, can handle indifferences in a convenient and computationally effi- cient manner, and also satisfies better candidate monotonicity properties. In view of this, our proposed rule seems to be a compelling solution for achieving proportional representation in voting settings. Keywords committee selection · multiwinner voting · proportional representation · single transferable vote. JEL Classification: C70 · D61 · D71 1 Introduction Of all modes in which a national representation can possibly be constituted, this one [STV] affords the best security for the intellectual qualifications de- sirable in the representatives—John Stuart Mill (Considerations on Represen- tative Government, 1861). arXiv:1708.07580v2 [cs.GT] 4 Jun 2018 H. Aziz · B. E. Lee Data61, CSIRO and UNSW, Sydney 2052 , Australia Tel.: +61-2-8306 0490 Fax: +61-2-8306 0405 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 2 Haris Aziz, Barton E. -

Selecting the Runoff Pair

Selecting the runoff pair James Green-Armytage New Jersey State Treasury Trenton, NJ 08625 [email protected] T. Nicolaus Tideman Department of Economics, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Blacksburg, VA 24061 [email protected] This version: May 9, 2019 Accepted for publication in Public Choice on May 27, 2019 Abstract: Although two-round voting procedures are common, the theoretical voting literature rarely discusses any such rules beyond the traditional plurality runoff rule. Therefore, using four criteria in conjunction with two data-generating processes, we define and evaluate nine “runoff pair selection rules” that comprise two rounds of voting, two candidates in the second round, and a single final winner. The four criteria are: social utility from the expected runoff winner (UEW), social utility from the expected runoff loser (UEL), representativeness of the runoff pair (Rep), and resistance to strategy (RS). We examine three rules from each of three categories: plurality rules, utilitarian rules and Condorcet rules. We find that the utilitarian rules provide relatively high UEW and UEL, but low Rep and RS. Conversely, the plurality rules provide high Rep and RS, but low UEW and UEL. Finally, the Condorcet rules provide high UEW, high RS, and a combination of UEL and Rep that depends which Condorcet rule is used. JEL Classification Codes: D71, D72 Keywords: Runoff election, two-round system, Condorcet, Hare, Borda, approval voting, single transferable vote, CPO-STV. We are grateful to those who commented on an earlier draft of this paper at the 2018 Public Choice Society conference. 2 1. Introduction Voting theory is concerned primarily with evaluating rules for choosing a single winner, based on a single round of voting. -

On the Specification and Verification of Voting Schemes

On the Specification and Verification of Voting Schemes Bernhard Beckert1, Rajeev Gor´e2, and Carsten Sch¨urmann3 1 Karlsruhe Institute of Technology [email protected] 2 The Australian National University [email protected] 3 IT University of Copenhagen [email protected] Abstract. The ability to count ballots by computers allows us to design new voting schemes that are arguably fairer than existing schemes de- signed for hand-counting. We argue that formal methods can and should be used to ensure that such schemes behave as intended and are con- form to the desired democratic properties. Specifically, we define two semantic criteria for single transferable vote (STV) schemes, formulated in first-order logic, and show how bounded model-checking can be used to test whether these criteria are met. As a case study, we then analyse an existing voting scheme for electing the board of trustees for a major international conference and discuss its deficiencies. 1 Introduction The goal of any social choice function is to compute an \optimal" choice from a given set of preferences. Voting schemes in elections are a prime example of such choice functions as they compute a seat distribution from a set of prefer- ences recorded on ballots. By voting scheme we mean a concrete description of a method for counting the ballots and computing which candidates are elected { as opposed to an actual computer implementation of such a scheme or a scheme describing the process of casting votes via computer. The difficulty in designing preferential voting schemes is that the optimisation criteria are not only multi- dimensional, but multi-dimensional on more than one level. -

Gerrymandering and Fair Districting in Parallel Voting Systems Arxiv

Gerrymandering and fair districting in parallel voting systems Igor Mandric1, Igor Roşca2, and Radu Buzatu3 1Department of Computer Science, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA 2Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chişinˇau,Moldova 3Department of Mathematics, Moldova State University, Chişinˇau, Moldova Abstract Switching from one electoral system to another one is frequently criticized by the opposition and is viewed as a means for the ruling party to stay in power. In particular, when the new electoral system is a parallel voting (or a single-member district) system, the ruling party is usually suspected of a bi- ased way of partitioning the state into electoral districts such that based on a priori knowledge it has more chances to win in a maximum possible number of districts. In this paper, we propose a new methodology for deciding whether a particular party benefits from a given districting map under a parallel voting system. As a part of our methodology, we formulate and solve several gerry- mandering problems. We showcased the application of our approach to the Moldovan parliamentary elections of 2019. Our results suggest that contrary to the arguments of previous studies, there is no clear evidence to consider that the districting map used in those elections was unfair. 1 Introduction arXiv:2002.06849v1 [physics.soc-ph] 17 Feb 2020 Political (re-)districting represents the task of partitioning a geographic area (e.g., a state or an administrative unit) into a given number of electoral districts subject to a predefined set of requirements [1]. Frequently, the requirements are formulated with respect to demographic and/or geographic peculiarities of the area [2]. -

Electoral Systems in the World's Most Robust Democracies

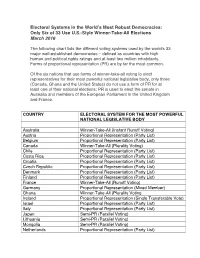

Electoral Systems in the World’s Most Robust Democracies: Only Six of 33 Use U.S.-Style Winner-Take-All Elections March 2016 The following chart lists the different voting systems used by the world's 33 major well-established democracies – defined as countries with high human and political rights ratings and at least two million inhabitants. Forms of proportional representation (PR) are by far the most common. Of the six nations that use forms of winner-take-all voting to elect representatives for their most powerful national legislative body, only three (Canada, Ghana and the United States) do not use a form of PR for at least one of their national elections; PR is used to elect the senate in Australia and members of the European Parliament in the United Kingdom and France. COUNTRY ELECTORAL SYSTEM FOR THE MOST POWERFUL NATIONAL LEGISLATIVE BODY Australia Winner-Take-All (Instant Runoff Voting) Austria Proportional Representation (Party List) Belgium Proportional Representation (Party List) Canada Winner-Take-All (Plurality Voting) Chile Proportional Representation (Party List) Costa Rica Proportional Representation (Party List) Croatia Proportional Representation (Party List) Czech Republic Proportional Representation (Party List) Denmark Proportional Representation (Party List) Finland Proportional Representation (Party List) France Winner-Take-All (Runoff Voting) Germany Proportional Representation (Mixed Member) Ghana Winner-Take-All (Plurality Voting Ireland Proportional Representation (Single Transferable Vote) Israel Proportional -

Notes on the Droop Quota

Notes on the Droop quota Jonathan Lundell & I D Hill Nicolaus Tideman (after Michael Dummett) calls this “(k+1)-proportionality for solid coalitions”, or (k+1)-PSC [2, p269]. 1 Introduction The Droop quota, like the Hare quota, is often rounded to an integer. From O’Neill’s description STV methods have historically used one of two quo- of the proposed BC STV rules [4]: tas: the Hare quota v/s (votes divided by seats) or The “Droop quota” will be the formula the Droop quota v/(s + 1) (votes divided by seats for calculating the number of votes re- plus one) [1, 2]. quired by a candidate for election in a The Hare quota v/s is the largest quota such that district. The quota formula is: s candidates can be elected. Methods employing the Hare quota typically deal in whole votes, and use the total number of valid integer portion of the calculation: !v/s". ballots cast in the district With the Hare quota, it is possible for a major- + 1 number of members ity bloc of voters to elect only a minority of seats, 1 + to be elected in particular when the number of seats is odd. The Droop quota, the smallest quota such that no more Fractions are ignored. candidates can be elected than there are seats to fill, addresses this problem. Furthermore, the Hare More compactly: !v/(s + 1) + 1". quota is vulnerable to strategic voting and vote man- Henry Droop himself defined his quota as agement, which the Droop quota makes much less mV/(n + 1) + i, where V voters have m votes likely to succeed.