Maori Values Can Reinvigorate a New Zealand Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Whare-Oohia: Traditional Maori Education for a Contemporary World

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. TE WHARE-OOHIA: TRADITIONAL MAAORI EDUCATION FOR A CONTEMPORARY WORLD A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Education at Massey University, Palmerston North, Aotearoa New Zealand Na Taiarahia Melbourne 2009 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS He Mihi CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 The Research Question…………………………………….. 5 1.2 The Thesis Structure……………………………………….. 6 CHAPTER 2: HISTORY OF TRADITIONAL MAAORI EDUCATION 9 2.1 The Origins of Traditional Maaori Education…………….. 9 2.2 The Whare as an Educational Institute……………………. 10 2.3 Education as a Purposeful Engagement…………………… 13 2.4 Whakapapa (Genealogy) in Education…………………….. 14 CHAPTER 3: LITERATURE REVIEW 16 3.1 Western Authors: Percy Smith;...……………………………………………… 16 Elsdon Best;..……………………………………………… 22 Bronwyn Elsmore; ……………………………………….. 24 3.2 Maaori Authors: Pei Te Hurinui Jones;..…………………………………….. 25 Samuel Robinson…………………………………………... 30 CHAPTER 4: RESEARCHING TRADITIONAL MAAORI EDUCATION 33 4.1 Cultural Safety…………………………………………….. 33 4.2 Maaori Research Frameworks…………………………….. 35 4.3 The Research Process……………………………………… 38 CHAPTER 5: KURA - AN ANCIENT SCHOOL OF MAAORI EDUCATION 42 5.1 The Education of Te Kura-i-awaawa;……………………… 43 Whatumanawa - Of Enlightenment..……………………… 46 5.2 Rangi, Papa and their Children, the Atua:…………………. 48 Nga Atua Taane - The Male Atua…………………………. 49 Nga Atua Waahine - The Female Atua…………………….. 52 5.3 Pedagogy of Te Kura-i-awaawa…………………………… 53 CHAPTER 6: TE WHARE-WAANANGA - OF PHILOSOPHICAL EDUCATION 55 6.1 Whare-maire of Tuhoe, and Tupapakurau: Tupapakurau;...……………………………………………. -

On the Repatriation of Māori Toi Moko Colleen Murphy a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requi

Talking Heads: On the Repatriation of Māori Toi Moko Colleen Murphy A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in the History of Art THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 2016 Murphy 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Whakawhetai (Acknowledgements) . 03 Text Introduction: Detached Heads . 04 Ta Moko Tattooing . 07 Early Contact with Europeans . 09 Changing Attitudes . 16 General H.G. Robley . 19 People on Display . 26 Western Displays of Māori Art and Artifacts . 30 The Māori Renaissance . 34 Repatriation Practices . 37 Legislation Related to Repatriation . 39 Conclusion: Ceremonial Repatriation . 41 Endnotes . 42 Bibliography . 46 Images . 50 Murphy 3 Whakawhetai (Acknowledgements) I would like to sincerely thank my faculty advisor Dr. David Doris for his indispensable guidance during this process. He continuously found time in his busy schedule to help me with my research, and I am incredibly grateful for his generosity, sense of humor and support. I am also grateful to Dr. Howard Lay for his assistance both in this project and throughout my career at the University of Michigan. He reaffirmed my love for the History of Art in his lectures both at Michigan and throughout France, and demonstrated unbelievable dedication to our seminar class. I am certain that my experience at Michigan would not have been the same without his mentorship. I am greatly appreciative of the staff at Te Papa Tongawera for their online resources and responses to my specific questions regarding their Repatriation Program, and the Library of the University of Wellington, New Zealand, which generously makes portions of the New Zealand Text Collection freely available online. -

Creation Narratives of Mahinga Kai

CREATION NARRATIVES OF MAHINGA KAI Mäori customary food-gathering sites and practices Chanel Phillips* Anne- Marie Jackson† Hauiti Hakopa‡ Abstract Mahinga kai, Mäori customary food-gathering sites and practices, emerged at the beginning of the creation narratives when the Mäori world was fi rst formed and atua roamed upon the face of the land. This paper critically evaluates the emergent discourses of mahinga kai within key Mäori creation narratives that stem from the Mäori worldview. The narratives selected for analysis were the following three creation narratives: the separation of Ranginui and Papa-tü- ä- nuku, the retribution of Tü- mata- uenga and the creation of humanity. The multiple discourses that emerge from these narratives involved mahinga kai as whakapapa, whanaungatanga, tikanga with the subsequent discourse of tapu, kaitiakitanga with the subsequent discourse of mauri and mätauranga. A discursive analysis of mahinga kai in Mäori creation narratives confi rms mahinga kai as an expression of Mäori worldview and reveals a myriad of understandings. Keywords mahinga kai, customary food gathering, creation narratives, Mäori worldview * Ngäti Hine, Ngäpuhi. PhD Candidate, School of Physical Education, Sport and Exercise Sciences, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand. Email: [email protected] † Ngäti Whätua, Ngäpuhi, Ngäti Wai, Ngäti Kahu o Whangaroa. Senior Lecturer, Mäori Physical Education and Health, School of Physical Education, Sport and Exercise Sciences, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand. ‡ Ngäti Tüwharetoa. Teaching Fellow, Mäori Physical Education and Health, School of Physical Education, Sport and Exercise Sciences, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand. DOI: 10.20507/MAIJournal.2016.5.1.5 64 C. -

Enhancing Mātauranga Māori and Global Indigenous Knowledge 1

Enhancing Mātauranga Māori and Global Indigenous Knowledge 1 Enhancing Mātauranga Māori and Global Indigenous Knowledge 2 Enhancing Mātauranga Māori and Global Indigenous Knowledge Me Mihi ka Tika Ko te kaupapa matua o tēnei pukapuka, ko te tūhono mai i ngā kāinga kōrero o te ao mātauranga Māori o te hinengaro tata, hinengaro tawhiti, ka whakakākahu atu ai i ngā mātauranga o te iwi taketake o te ao whānui. E anga whakamua ai ngā papa kāinga kōrero mātauranga Māori me te mātauranga o ngā iwi taketake, ka tika kia hao atu aua kāinga kōrero ki runga i tēnei manu rangatira o te ao rere tawhiti, o te ao rere pāmamao, te toroa. Ko te toroa e aniu atu rā hai kawe i te kupu kōrero o te hinengaro mātauranga Māori me ngā reo whakaū o ngā tāngata taketake o ngā tai e whā o Ranginui e tū atu nei, o Papatūānuku e takoto iho nei. Ko te ātaahua ia, ka noho tahi mai te toroa me Te Waka Mātauranga hai ariā matua, hai hēteri momotu i ngā kāinga kōrero ki ngā tai timu, tai pari o ngā tai e whā o te ao whānui. He mea whakatipu tātau e tō tātau Kaiwhakaora, kia whānui noa atu ngā kokonga kāinga o te mātauranga, engari nā runga i te whānui noa atu o aua kokonga kāinga ka mōhio ake tātau ki a tātau ake. He mea nui tēnei. Ko te whakangungu rākau, ko te pourewa taketake ko te whakaaro nui, ko te māramatanga o ō tātau piringa ka pai kē atu. Ka huaina i te ao, i te pō ka tipu, ka tipu te pātaka kōrero. -

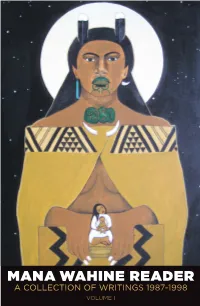

MANA WAHINE READER a COLLECTION of WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader a Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I

MANA WAHINE READER A COLLECTION OF WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I I First Published 2019 by Te Kotahi Research Institute Hamilton, Aotearoa/ New Zealand ISBN: 978-0-9941217-6-9 Education Research Monograph 3 © Te Kotahi Research Institute, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Design Te Kotahi Research Institute Cover illustration by Robyn Kahukiwa Print Waikato Print – Gravitas Media The Mana Wahine Publication was supported by: Disclaimer: The editors and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the material within this reader. Every attempt has been made to ensure that the information in this book is correct and that articles are as provided in their original publications. To check any details please refer to the original publication. II Mana Wahine Reader | A Collection of Writings 1987-1998, Volume I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I Edited by: Leonie Pihama, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Naomi Simmonds, Joeliee Seed-Pihama and Kirsten Gabel III Table of contents Poem Don’t Mess with the Māori Woman - Linda Tuhiwai Smith 01 Article 01 To Us the Dreamers are Important - Rangimarie Mihomiho Rose Pere 04 Article 02 He Aha Te Mea Nui? - Waerete Norman 13 Article 03 He Whiriwhiri Wahine: Framing Women’s Studies for Aotearoa Ngahuia Te Awekotuku 19 Article 04 Kia Mau, Kia Manawanui -

Maori Cartography and the European Encounter

14 · Maori Cartography and the European Encounter PHILLIP LIONEL BARTON New Zealand (Aotearoa) was discovered and settled by subsistence strategy. The land east of the Southern Alps migrants from eastern Polynesia about one thousand and south of the Kaikoura Peninsula south to Foveaux years ago. Their descendants are known as Maori.1 As by Strait was much less heavily forested than the western far the largest landmass within Polynesia, the new envi part of the South Island and also of the North Island, ronment must have presented many challenges, requiring making travel easier. Frequent journeys gave the Maori of the Polynesian discoverers to adapt their culture and the South Island an intimate knowledge of its geography, economy to conditions different from those of their small reflected in the quality of geographical information and island tropical homelands.2 maps they provided for Europeans.4 The quick exploration of New Zealand's North and The information on Maori mapping collected and dis- South Islands was essential for survival. The immigrants required food, timber for building waka (canoes) and I thank the following people and organizations for help in preparing whare (houses), and rocks suitable for making tools and this chapter: Atholl Anderson, Canberra; Barry Brailsford, Hamilton; weapons. Argillite, chert, mata or kiripaka (flint), mata or Janet Davidson, Wellington; John Hall-Jones, Invercargill; Robyn Hope, matara or tuhua (obsidian), pounamu (nephrite or green Dunedin; Jan Kelly, Auckland; Josie Laing, Christchurch; Foss Leach, stone-a form of jade), and serpentine were widely used. Wellington; Peter Maling, Christchurch; David McDonald, Dunedin; Bruce McFadgen, Wellington; Malcolm McKinnon, Wellington; Marian Their sources were often in remote or mountainous areas, Minson, Wellington; Hilary and John Mitchell, Nelson; Roger Neich, but by the twelfth century A.D. -

Haka and Hula Representations in Tourism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Haka and hula representations in tourism A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington for the degree of Master of Arts in the School of Māori Studies (Te Kawa a Māui) Victoria University of Wellington November 2009 By Acushla Deanne O’Carroll I Abstract Haka and hula performances tell stories that represent histories, traditions, protocols and customs of the Māori and Hawai’ian people and give insight into their lives and the way that they see the world. The way that haka and hula performances are represented is being tested, as the dynamics of the tourism industry impact upon and influence the art forms. If allowed, these impacts and influences can affect the performances and thus manipulate or change the way that haka and hula are represented. Through an understanding of the impacts and influences of tourism on haka and hula performances, as well as an exploration of the cultures’ values, cultural representations effective existence within the tourism industry can be investigated. This thesis will incorporate the perspectives of haka and hula practitioners and discuss the impacts and influences on haka and hula performances in tourism. The research will also explore and discuss the ways in which cultural values and representations can effectively co-exist within tourism. II Mihimihi I te riu o te whenua Te Rua o te Moko I raro i te maru o Taranaki I ruia i ngā kākano o te ora Kia ora ai te hapū, ko Puawhato te Rangatira! Ko Taranaki te maunga Ko Aotea te waka Ko Waingōngōrō te awa Ko Ngāruahine Rangi, Ngāti Ruanui me Te Ātiawa ngā iwi Ko Otaraua me Kanihi-Umutahi ngā hapū Ko Otaraua me Kanihi-Māwhitiwhiti ngā marae Ko Acushla Deanne O’Carroll tōku ingoa Tēnā tātou katoa III Dedication This thesis is dedicated to all of the participants involved in this research. -

Traditional Maori Parenting

TRADITIONAL MAORI PARENTING An Historical Review of Literature of Traditional Maori Child Rearing Practices in Pre-European Times Professor Kuni Jenkins, PhD. Helen Mountain Harte M.A. Te Kahui Mana Ririki. Auckland, New Zealand. March 2011 Published by Te Kahui Mana Ririki, Auckland, New Zealand March 2011 This publication was prepared by Te Kahui Mana Ririki, with funding from the Office of the Children’s Commissioner. The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official views, opinions or position of the Children’s Commissioner. ii Karakia Whakatuwheratanga Toitu te rangi Toitu te whenua Toitu te aroha o te Atua Toitu ona manaakitanga katoa Mauriora e Te Ariki Matua, Tama, Wairua Tapu. Amine. iii Whakapuakitanga/Foreword When I read these research findings I immediately think of the opening stanza of the Ode to Immortality, by William Wordsworth: The child is but father of the man, And I could wish my days to be In such natural piety. We cannot turn back the clock but we can redeem the present by looking to the past; and glean from it lessons that might give us all a better sense of what is possible in the arena of parenting. The research done by my whanaunga and colleagues captures images that we could well emulate as we struggle to find answers to an ever increasing circle of seemingly unstoppable violence to our children. The history revealed tells us it is possible, all we need is the will to achieve. One of our tasks as Te Kahui Mana Ririki has been to dig deep into our own reo and mine the riches that are there – and from them espouse a philosophy that engenders hope and confidence. -

Ko Rüamoko E Ngunguru Nei Reading Between the Lines

KO RÜAMOKO E NGUNGURU NEI READING BETWEEN THE LINES ROBERT JAHNKE Massey University—Palmerston North Ko Rüaumoko e ngunguru nei ‘Rüaumoko [the earthquake god] rumbles’ is a line from a Ngäti Porou haka ‘war dance’. The rumbling of Rüaumoko is a metaphor for an uri ‘descendant’ of Ngäti Porou challenging accepted körero ‘discourse’ that shapes our interpretation of tribal narratives and traditional arts. At the heart of my wero ‘challenge’ is the uncritical acceptance of early translations of a Mäori text that led to a number of misinterpretations by Roger Neich. I undertake detailed critical textual analysis to demonstrate how crucial such analysis is for ethno-aesthetic insight into what Neich (2001: 123) has called “traditional Maori concepts of art”.1 A comparative textual method is employed to critique S. Percy Smith’s and Elsdon Best’s translations of the Mataora narrative,2 from the Hawkes Bay and Wairarapa tribal areas, about the origin of tattoo, weaving and carving to demonstrate the necessity of revisiting Mäori texts in order to uncover the narrative’s huna ‘hidden’ meaning. Smith published a two-volume work called The Lore of the Whare Wananga in 1913 and 1915 based on the transcripts of Te Matorohanga and Nepia Pohuhu recorded by Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury in the 1860s (Simmons 2007). The Mataora narrative appears in volume one of The Lore of the Whare Wananga with an original Mäori text and Smith’s translation. Best published his version of the Mataora narrative in Maori Religion and Mythology Part I in 1924. I have included Best’s translation in my analysis because he recorded a revised version of the Mataora narrative that appears to indicate the Te Matorohanga text as the source, despite his exclusion of some significant lines and reconfiguration of some passages (Best 1995: 226-30). -

Ments of Maui: Notes on Tricksters

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by AUT Scholarly Commons THE 10 PREDICA- MENTS OF MAUI: NOTES ON TRICKSTERS Natalie Robertson A mover and groover, the Trickster is a god of the crossroads. You might come across this ruler of travellers, the road-opener, on the highway or you could bump into this deity of contradictions and opportunities on a dusty country road. Maybe you’ll Bookmark from Francis Alÿs, The Prophet and the Fly, stumble upon the ruler of primordial light and of the rickster was out walking, walking the dog… published Turner, Madrid, 2003 daytime sun as it travels across the sky in the town T square. A messenger in transit between this world and the next, either above or below, the Trickster can be the anarchist who challenges governance and societal structure, looking sometimes like a rebel without a cause, yet may be the defender of deeply held cultural values. As a wandering figure that is always on the move with an insatiable appetite or desire, a rebel without a pause, it is impossible to present a singular characterisation, for the Trickster appears in most cultures across the world. Weaving between the polar positions of the culturally specific ‘no two Tricksters are alike’ and the mythic archetype ‘one Trickster fits all’, this essay blatantly thieves for selfish ends, retrieving connections between Trickster stories from ‘magic realism’ literature of South America and the art practice of Francis Alÿs, a 17 Tricksters27 Belgian artist living in Mexico City. Taking Alÿs’ notes Abenaki mythology .. -

Māori and Christianity

A Kaupapa Māori study of the positive impacts of syncretism on the development of Christian faith among Māori from my faith-world perspective Byron William Rangiwai A thesis submitted to the University of Otago in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) He mea whakaritea e Reverend Mahaki Albert mā roto i ngā karakia i mua i taku tuku ki ngā kaimāka June 2019 Dedication This work is dedicated to my late maternal grandmother, Rēpora Marion Brown (nee Maki) who inspired and maintained my faith in the Divine. Born in 1940. Passed away 1 December 2017. i Tangihanga Nan, you lie in the wharemate At Patuheuheu marae Adorned with a taonga That I gave you A pounamu Hei Tiki Kahurangi grade—fine, light And without blemish Your passing cuts deep Into my fragile, broken heart The tears sting my cheeks The hūpē dries on my black t-shirt Like the trails of a dozen snails Glistening in the summer sun The grief drains me, vampirically Like a squirming black leach Pulsating and feasting On the arteries of my aroha Its sharp mouthpiece gnawing Intensely and purposefully Images of you unwell and Dying, haunt my thoughts I recall your suffering Each time I close my eyes Hospital scenes and last moments Projected on my eyelids In High Definition realness When you made your descent Beneath Papatūānuku’s skin ii I watched from afar and wept Hinenuitepō’s embrace And Jesus’ promise of heaven Did little to comfort me Your chrome nameplate And myriad plastic flowers Now mark your resting place My whānau are my healers The rongoā for my pain Their presence and love Begins the healing As does the incessant crying Behind closed doors When I am alone Moe mai rā e te māreikura o te whakapono. -

Mātauranga Māori in Psychology: Contributions to an Indigenous Psychology

MĀTAURANGA MĀORI IN PSYCHOLOGY: CONTRIBUTIONS TO AN INDIGENOUS PSYCHOLOGY 16INT20 KENDREX KEREOPA-WOON DR WAIKAREMOANA WAITOKI INTERNSHIP REPORT UNIVERSITY OF WAIKATO 2017 This internship report was produced by the authors as part of a supported internship project under the supervision of the named supervisor and funded by Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga. The report is the work of the named intern and researchers and has been posted here as provided. It does not represent the views of Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga and any correspondence about the content should be addressed directly to the authors of the report. For more information on Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga and its research, visit the website on www.maramatanga.ac.nz Project Title: Mātauranga Māori in psychology: Contributions to an Indigenous Psychology A research report completed for the requirements of the Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga Summer Internship Programme 2016-2017 Supervisor: Dr. Waikaremoana Waitoki Intern: Kendrex Kereopa-Woon Institution: University of Waikato ii Abstract I Te Kore, ki Te Pō, ki Te Ao Mārama “Out of nothingness, into the night, into the world of light” -Whakataukī A long time ago, in a time where there was total darkness Māori were once whole, and within this wholeness we were balanced, and from this we understood. Within that balance it enabled us to use our potential so that we could move between worlds and have the ability to seek clarity, learn, and illuminate the boundless possibilities and opportunities to grow. This enabled us to seek comfort in understanding more about ourselves, our abilities, our environment, and analysing the contributions to our ongoing knowledge bases as Māori.