Creation Narratives of Mahinga Kai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rangi Above/Papa Below, Tangaroa Ascendant, Water All Around Us: Austronesian Creation Myths

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2005 Rangi above/Papa below, Tangaroa ascendant, water all around us: Austronesian creation myths Amy M Green University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Green, Amy M, "Rangi above/Papa below, Tangaroa ascendant, water all around us: Austronesian creation myths" (2005). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1938. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/b2px-g53a This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RANGI ABOVE/ PAPA BELOW, TANGAROA ASCENDANT, WATER ALL AROUND US: AUSTRONESIAN CREATION MYTHS By Amy M. Green Bachelor of Arts University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2004 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in English Department of English College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1436751 Copyright 2006 by Green, Amy M. -

ASTROBIOLOGY ORIGINS and WHAKAPAPA MĀORI of How the Phenomenological World Came the Potential: - a PARALLEL

Aotearoa – New Zealand IN THE BEGINNING... Māori Ways of Te Kore the nothingness, Knowing ASTROBIOLOGY ORIGINS AND WHAKAPAPA MĀORI of how the phenomenological world came the potential: - A PARALLEL. I.H. Mogoșanu1,2, T.N.W.T.A. Waaka 3, J.G. Blank1,2,4, K.A. Campbell1,5, K.P. Paul6, C.L.R. Newton7,8, E.H. to be. In the creation of the world, Rang- Tait6,7,8,9, E. Gregory10, 1New Zealand Astrobiology Network inui and Papatūānuku were the first physi- (Wellington New Zealand; [email protected]), 2Blue before the Big Bang Marble Space Institute of Science (Seattle WA USA), 3Society cal representations of ancestors that link us for Māori Astronomy, Research, and Traditions SMART (Wel- back to the creation of the Universe. Their - lington NZ), University of Otago, 4NASA Ames Research Cen- children ruled the natural world. Tāwhiri- Te Po ter (Moffett Field, CA USA),5 School of Environment and Te Ao Mārama – Centre for Fundamental Inquiry, University of matea was guardian of the winds, Tangaroa Auckland, Auckland, 1142, New Zealand, 6Ngati Whakaue, 7Te was guardian of the sea, Tāne-mahuta of Taumata O Ngati Whakaue Iho Ake, Rotorua, New Zealand, the forest, Tūmatauenga of war and man- the night: 8Ngāti Pikiao, Ngāti Manawa, 9Tuhoe, 10Waikato, Maniapoto. kind, Rongo of cultivated foods and Haumie of uncultivated foods. The children gave rise the Universe is The unwritten teachings of Mātauranga to both humans and all aspects of the natu- Māori (Māori way of knowing) in Aotearoa – ral world. New Zealand encapsulate the traditional way just energy, of relating to and rediscovering one’s own Mātauranga Māori is based on empirical linkage to the land, sea and sky based on the observations of the environment to which first atoms emerge connectedness that knowledge has with re- Māori are profoundly connected. -

Rangi and Papa Script

Rangi and Papa script Benjamin Burrell Animation: Ink droplets on watery canvas. 0:01 DARKNESS, THE BEGINNING OF TIME AND SPACE. WE SEE POWERFUL MUSCULAR GODS CRAMMED TOGETHER IN DARKNESS, RESTLESS. MONOTONE BODY SHAPES CURLED IN TO FOETAL POSITIONS REST AND SLUMBER. Ranginui and Papatūānuku are the primordial parents, the sky father and the earth mother who lie locked together in a tight embrace. They have many sons, who are forced to live in the cramped darkness between them. 0:18 WE SEE SOME MOVEMENT, AN IDEA GROWS AND WE SEE A SOFT GLOW. THE GODS COMMUNICATE. SOFT SHAPES MOVE BUT ARE INDISTINGUISHABLE. These children grow. 0:24 PANNING SHOT AROUND THE FACES OF THE CIRCLE OF GODS, THEY SIT CROSS LEGGED IN DEEP DISCUSSION, SERIOUS EXPRESSIONS AND GRAVE FACES. The god children discuss among themselves what it would be like to live in the light. Tūmatauenga, the fiercest of the children, proposes that the best solution to their predicament is to kill their parents. But his brother Tāne, god of forests and birds, disagrees, suggesting that it is better to push them apart, to let Ranginui be as a stranger to them in the sky above while Papatūānuku will remain below to nurture them. 0:33 TU THE GOD OF WAR FLEXES HIS MUSCLES AND WE SEE COLOUR FOR THE FIRST TIME, RED EYES AND HANDS 0:41 WE SEE THE FACES OF THE SKY FATHER AND EARTH MOTHER AND THEIR ARMS WRAPPED TIGHTLY AROUND EACH OTHER. RANGI WITH HIS LONG FLOWING HAIR THAT CHANGES FROM DARK BLUE TO LIGHT BLUE AND PAPA WITH HAIR LIKE ROOTS THAT CHANGE TO TREES AND LEAVES AT THE ENDS. -

The Whare-Oohia: Traditional Maori Education for a Contemporary World

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. TE WHARE-OOHIA: TRADITIONAL MAAORI EDUCATION FOR A CONTEMPORARY WORLD A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Education at Massey University, Palmerston North, Aotearoa New Zealand Na Taiarahia Melbourne 2009 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS He Mihi CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 The Research Question…………………………………….. 5 1.2 The Thesis Structure……………………………………….. 6 CHAPTER 2: HISTORY OF TRADITIONAL MAAORI EDUCATION 9 2.1 The Origins of Traditional Maaori Education…………….. 9 2.2 The Whare as an Educational Institute……………………. 10 2.3 Education as a Purposeful Engagement…………………… 13 2.4 Whakapapa (Genealogy) in Education…………………….. 14 CHAPTER 3: LITERATURE REVIEW 16 3.1 Western Authors: Percy Smith;...……………………………………………… 16 Elsdon Best;..……………………………………………… 22 Bronwyn Elsmore; ……………………………………….. 24 3.2 Maaori Authors: Pei Te Hurinui Jones;..…………………………………….. 25 Samuel Robinson…………………………………………... 30 CHAPTER 4: RESEARCHING TRADITIONAL MAAORI EDUCATION 33 4.1 Cultural Safety…………………………………………….. 33 4.2 Maaori Research Frameworks…………………………….. 35 4.3 The Research Process……………………………………… 38 CHAPTER 5: KURA - AN ANCIENT SCHOOL OF MAAORI EDUCATION 42 5.1 The Education of Te Kura-i-awaawa;……………………… 43 Whatumanawa - Of Enlightenment..……………………… 46 5.2 Rangi, Papa and their Children, the Atua:…………………. 48 Nga Atua Taane - The Male Atua…………………………. 49 Nga Atua Waahine - The Female Atua…………………….. 52 5.3 Pedagogy of Te Kura-i-awaawa…………………………… 53 CHAPTER 6: TE WHARE-WAANANGA - OF PHILOSOPHICAL EDUCATION 55 6.1 Whare-maire of Tuhoe, and Tupapakurau: Tupapakurau;...……………………………………………. -

Maori Values Can Reinvigorate a New Zealand Philosophy

Maori Values Can Reinvigorate a New Zealand Philosophy Piripi Whaanga A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Philosophy. Philosophy Department Victoria University of Wellington 2012 CONTENTS CONTENTS ....................................................................................................................................................2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ..................................................................................................................................4 ABSTRACT .....................................................................................................................................................4 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................7 Thesis method ........................................................................................................................................11 Thesis chapter division ...........................................................................................................................12 CHAPTER ONE: PRE-PAKEHA MAORI VALUES .............................................................................................17 Tikanga of mauri .....................................................................................................................................17 Virtues as ethics .....................................................................................................................................20 -

On the Repatriation of Māori Toi Moko Colleen Murphy a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requi

Talking Heads: On the Repatriation of Māori Toi Moko Colleen Murphy A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in the History of Art THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 2016 Murphy 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Whakawhetai (Acknowledgements) . 03 Text Introduction: Detached Heads . 04 Ta Moko Tattooing . 07 Early Contact with Europeans . 09 Changing Attitudes . 16 General H.G. Robley . 19 People on Display . 26 Western Displays of Māori Art and Artifacts . 30 The Māori Renaissance . 34 Repatriation Practices . 37 Legislation Related to Repatriation . 39 Conclusion: Ceremonial Repatriation . 41 Endnotes . 42 Bibliography . 46 Images . 50 Murphy 3 Whakawhetai (Acknowledgements) I would like to sincerely thank my faculty advisor Dr. David Doris for his indispensable guidance during this process. He continuously found time in his busy schedule to help me with my research, and I am incredibly grateful for his generosity, sense of humor and support. I am also grateful to Dr. Howard Lay for his assistance both in this project and throughout my career at the University of Michigan. He reaffirmed my love for the History of Art in his lectures both at Michigan and throughout France, and demonstrated unbelievable dedication to our seminar class. I am certain that my experience at Michigan would not have been the same without his mentorship. I am greatly appreciative of the staff at Te Papa Tongawera for their online resources and responses to my specific questions regarding their Repatriation Program, and the Library of the University of Wellington, New Zealand, which generously makes portions of the New Zealand Text Collection freely available online. -

Te Wairua Kōmingomingo O Te Māori = the Spiritual Whirlwind of the Māori

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. TE WAIRUA KŌMINGOMINGO O TE MĀORI THE SPIRITUAL WHIRLWIND OF THE MĀORI A thesis presented for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Māori Studies Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand Te Waaka Melbourne 2011 Abstract This thesis examines Māori spirituality reflected in the customary words Te Wairua Kōmingomingo o te Maori. Within these words Te Wairua Kōmingomingo o te Māori; the past and present creates the dialogue sources of Māori understandings of its spirituality formed as it were to the intellect of Māori land, language, and the universe. This is especially exemplified within the confinements of the marae, a place to create new ongoing spiritual synergies and evolving dialogues for Māori. The marae is the basis for meaningful cultural epistemological tikanga Māori customs and traditions which is revered. Marae throughout Aotearoa is of course the preservation of the cultural and intellectual rights of what Māori hold as mana (prestige), tapu (sacred), ihi (essence) and wehi (respect) – their tino rangatiratanga (sovereignty). This thesis therefore argues that while Christianity has taken a strong hold on Māori spirituality in the circumstances we find ourselves, never-the-less, the customary, and traditional sources of the marae continue to breath life into Māori. This thesis also points to the arrival of the Church Missionary Society which impacted greatly on Māori society and accelerated the advancement of colonisation. -

Enhancing Mātauranga Māori and Global Indigenous Knowledge 1

Enhancing Mātauranga Māori and Global Indigenous Knowledge 1 Enhancing Mātauranga Māori and Global Indigenous Knowledge 2 Enhancing Mātauranga Māori and Global Indigenous Knowledge Me Mihi ka Tika Ko te kaupapa matua o tēnei pukapuka, ko te tūhono mai i ngā kāinga kōrero o te ao mātauranga Māori o te hinengaro tata, hinengaro tawhiti, ka whakakākahu atu ai i ngā mātauranga o te iwi taketake o te ao whānui. E anga whakamua ai ngā papa kāinga kōrero mātauranga Māori me te mātauranga o ngā iwi taketake, ka tika kia hao atu aua kāinga kōrero ki runga i tēnei manu rangatira o te ao rere tawhiti, o te ao rere pāmamao, te toroa. Ko te toroa e aniu atu rā hai kawe i te kupu kōrero o te hinengaro mātauranga Māori me ngā reo whakaū o ngā tāngata taketake o ngā tai e whā o Ranginui e tū atu nei, o Papatūānuku e takoto iho nei. Ko te ātaahua ia, ka noho tahi mai te toroa me Te Waka Mātauranga hai ariā matua, hai hēteri momotu i ngā kāinga kōrero ki ngā tai timu, tai pari o ngā tai e whā o te ao whānui. He mea whakatipu tātau e tō tātau Kaiwhakaora, kia whānui noa atu ngā kokonga kāinga o te mātauranga, engari nā runga i te whānui noa atu o aua kokonga kāinga ka mōhio ake tātau ki a tātau ake. He mea nui tēnei. Ko te whakangungu rākau, ko te pourewa taketake ko te whakaaro nui, ko te māramatanga o ō tātau piringa ka pai kē atu. Ka huaina i te ao, i te pō ka tipu, ka tipu te pātaka kōrero. -

Religious Education Programme

Creation and Co-Creation LEARNING STRAND: THEOLOGY RELIGIOUS EDUCATION PROGRAMME FOR CATHOLIC SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND 9E THE LOGO The logo is an attempt to express Faith as an inward and outward journey. This faith journey takes us into our own hearts, into the heart of the world and into the heart of Christ who is God’s love revealed. In Christ, God transforms our lives. We can respond to his love for us by reaching out and loving one another. The circle represents our world. White, the colour of light, represents God. Red is for the suffering of Christ. Red also represents the Holy Spirit. Yellow represents the risen Christ. The direction of the lines is inwards except for the cross, which stretches outwards. Our lives are embedded in and dependent upon our environment (green and blue) and our cultures (patterns and textures). Mary, the Mother of Jesus Christ, is represented by the blue and white pattern. The blue also represents the Pacific… Annette Hanrahan RSCJ Cover: Creation / Michelangelo / Sistine Chapel GETTY IMAGES Creation and Co-Creation LEARNING STRAND: THEOLOGY GETTY IMAGES 9E © 2014 National Centre for Religious Studies First published 1991 No part of this document may be reproduced in any way, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, without the prior permission of the publishers. Imprimatur + Leonard Boyle DD Bishop of Dunedin Episcopal Deputy for Religious Studies October 2001 Authorised by the New Zealand Catholic Bishops’ Conference. Design & Layout: Devine Graphics PO Box 5954 Dunedin New Zealand Published By: National Centre for Religious Studies Catholic Centre PO Box 1937 Wellington New Zealand Printed By: Printlink 33-43 Jackson Street Petone Private Bag 39996 Wellington Mail Centre Lower Hutt 5045 Māori terms are italicised in the text. -

Ngā Atua Māori

Ngā Atua Māori Student Name: ______________________ CONTENTS I te Tīmatanga – In the Beginning ...................................................................................... 2 He Karakia ...................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 He Kōrero Tīmatanga – The Creation Mythology .......................................................... 3 Papatūānuku – Our Earth Mother ....................................................................................... 4 Ko wai ia? Who is She? .................................................................................................. 4 Personifying Papatūānuku .............................................................................................. 5 Papatūānuku, our Mother ................................................................................................ 6 Ranginui – The Skyfather ................................................................................................... 7 Ngā Tamariki – Their Children .......................................................................................... 8 Tawhirimātea – The God of Wind & Weather ............................................................... 8 Tāne Māhuta – The God of the Forest ............................................................................ 8 Tūmātauenga – The God of War & People ................................................................... -

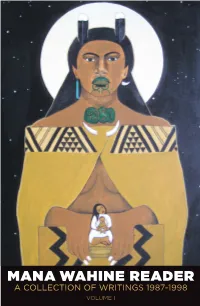

MANA WAHINE READER a COLLECTION of WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader a Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I

MANA WAHINE READER A COLLECTION OF WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I I First Published 2019 by Te Kotahi Research Institute Hamilton, Aotearoa/ New Zealand ISBN: 978-0-9941217-6-9 Education Research Monograph 3 © Te Kotahi Research Institute, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Design Te Kotahi Research Institute Cover illustration by Robyn Kahukiwa Print Waikato Print – Gravitas Media The Mana Wahine Publication was supported by: Disclaimer: The editors and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the material within this reader. Every attempt has been made to ensure that the information in this book is correct and that articles are as provided in their original publications. To check any details please refer to the original publication. II Mana Wahine Reader | A Collection of Writings 1987-1998, Volume I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I Edited by: Leonie Pihama, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Naomi Simmonds, Joeliee Seed-Pihama and Kirsten Gabel III Table of contents Poem Don’t Mess with the Māori Woman - Linda Tuhiwai Smith 01 Article 01 To Us the Dreamers are Important - Rangimarie Mihomiho Rose Pere 04 Article 02 He Aha Te Mea Nui? - Waerete Norman 13 Article 03 He Whiriwhiri Wahine: Framing Women’s Studies for Aotearoa Ngahuia Te Awekotuku 19 Article 04 Kia Mau, Kia Manawanui -

Maori Cartography and the European Encounter

14 · Maori Cartography and the European Encounter PHILLIP LIONEL BARTON New Zealand (Aotearoa) was discovered and settled by subsistence strategy. The land east of the Southern Alps migrants from eastern Polynesia about one thousand and south of the Kaikoura Peninsula south to Foveaux years ago. Their descendants are known as Maori.1 As by Strait was much less heavily forested than the western far the largest landmass within Polynesia, the new envi part of the South Island and also of the North Island, ronment must have presented many challenges, requiring making travel easier. Frequent journeys gave the Maori of the Polynesian discoverers to adapt their culture and the South Island an intimate knowledge of its geography, economy to conditions different from those of their small reflected in the quality of geographical information and island tropical homelands.2 maps they provided for Europeans.4 The quick exploration of New Zealand's North and The information on Maori mapping collected and dis- South Islands was essential for survival. The immigrants required food, timber for building waka (canoes) and I thank the following people and organizations for help in preparing whare (houses), and rocks suitable for making tools and this chapter: Atholl Anderson, Canberra; Barry Brailsford, Hamilton; weapons. Argillite, chert, mata or kiripaka (flint), mata or Janet Davidson, Wellington; John Hall-Jones, Invercargill; Robyn Hope, matara or tuhua (obsidian), pounamu (nephrite or green Dunedin; Jan Kelly, Auckland; Josie Laing, Christchurch; Foss Leach, stone-a form of jade), and serpentine were widely used. Wellington; Peter Maling, Christchurch; David McDonald, Dunedin; Bruce McFadgen, Wellington; Malcolm McKinnon, Wellington; Marian Their sources were often in remote or mountainous areas, Minson, Wellington; Hilary and John Mitchell, Nelson; Roger Neich, but by the twelfth century A.D.