Third Declension

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter One Phonetic Change

CHAPTERONE PHONETICCHANGE The investigation of the nature and the types of changes that affect the sounds of a language is the most highly developed area of the study of language change. The term sound change is used to refer, in the broadest sense, to alterations in the phonetic shape of segments and suprasegmental features that result from the operation of phonological process es. The pho- netic makeup of given morphemes or words or sets of morphemes or words also may undergo change as a by-product of alterations in the grammatical patterns of a language. Sound change is used generally to refer only to those phonetic changes that affect all occurrences of a given sound or class of sounds (like the class of voiceless stops) under specifiable phonetic conditions . It is important to distinguish between the use of the term sound change as it refers tophonetic process es in a historical context , on the one hand, and as it refers to phonetic corre- spondences on the other. By phonetic process es we refer to the replacement of a sound or a sequenceof sounds presenting some articulatory difficulty by another sound or sequence lacking that difficulty . A phonetic correspondence can be said to exist between a sound at one point in the history of a language and the sound that is its direct descendent at any subsequent point in the history of that language. A phonetic correspondence often reflects the results of several phonetic process es that have affected a segment serially . Although phonetic process es are synchronic phenomena, they often have diachronic consequences. -

Third Declension, That Is, Consonant-Stem Nouns; Patterns I

Chapter 7: Third-Declension Nouns Chapter 7 covers the following: third declension, that is, consonant-stem nouns; patterns in the formation of the nominative singular of third declension; and the agreement between third- declension nouns and first/second-declension adjectives. At the end of the lesson, we’ll review the vocabulary which you should memorize in this chapter. There is only one important rule to remember here: the genitive singular ending in third declension is -is . We’ve already encountered first- and second-declension nouns. Now we’ll address the third. A fair question to ask, and one which some of you may be asking, is why is there a third declension at all? Third declension is Latin’s “catch-all” category for nouns. Into it have been put all nouns whose bases end with consonants ─ any consonant! That makes third declension very different from first and second declension. First declension, as you’ll remember, is dominated by a-stem nouns like femina and cura . Second declension is dominated by o- or u-stem nouns like amicus or oculus . Those vowels give those declensions a certain consistency, but the same is not true of third declension where one form, the nominative singular, is affected by the fact that its ending -s runs into the wide variety of consonants found at the ends of the bases of third-declension nouns, and the collision of those consonants causes irregular forms to appear in the nominative singular. That’s the bad news. The good news is that only one case and number is affected by this, the nominative singular. -

Animacy, Definiteness, and Case in Cappadocian and Other

Animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and other Asia Minor Greek dialects* Mark Janse Ghent University and Roosevelt Academy, Middelburg This article discusses the relation between animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and several other Asia Minor Greek dialects. Animacy plays a decisive role in the assignment of Greek and Turkish nouns to the various Cappadocian noun classes. The development of morphological definiteness is due to Turkish interference. Both features are important for the phenom- enon of differential object marking which may be considered one of the most distinctive features of Cappadocian among the Greek dialects. Keywords: Asia Minor Greek dialectology, Cappadocian, Farasiot, Lycaonian, Pontic, animacy, definiteness, case, differential object marking, Greek–Turkish language contact, case typology . Introduction It is well known that there is a crosslinguistic correlation between case marking and animacy and/or definiteness (e.g. Comrie 1989:128ff., Croft 2003:166ff., Linguist List 9.1653 & 9.1726). In nominative-accusative languages, for in- stance, there is a strong tendency for subjects of active, transitive clauses to be more animate and more definite than objects (for Greek see Lascaratou 1994:89). Both animacy and definiteness are scalar concepts. As I am not con- cerned in this article with pronouns and proper names, the person and referen- tiality hierarchies are not taken into account (Croft 2003:130):1 (1) a. animacy hierarchy human < animate < inanimate b. definiteness hierarchy definite < specific < nonspecific Journal of Greek Linguistics 5 (2004), 3–26. Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 09:55:21PM via free access issn 1566–5844 / e-issn 1569–9856 © John Benjamins Publishing Company 4 Mark Janse With regard to case marking, there is a strong tendency to mark objects that are high in animacy and/or definiteness and, conversely, not to mark ob- jects that are low in animacy and/or definiteness. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Class Slides

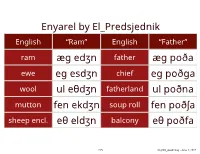

Enyarel by El_Predsjednik English “Ram” English “Father” ram æg edʒn father æg poða ewe eg esdʒn chief eg poðga wool ul eθdʒn fatherland ul poðna mutton fen ekdʒn soup roll fen poðʃa sheep encl. eθ eldʒn balcony eθ poðfa 215 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 HIGH VALYRIAN 216 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 The common language of the Valyrian Freehold, a federation in Essos that was destroyed by the Doom before the series begins. 217 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 218 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 ??????? High Valyrian ?????? 219 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Valar morghulis. “ALL men MUST die.” Valar dohaeris. “ALL men MUST serve.” 220 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Singular, Plural, Collective 221 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Large Number Collective Plural 222 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Paucal Large Number Collective Plural 223 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N kastor qintir “green turtle” 224 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val kaːr “man heap” 225 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *valhaːr > *valhar > valar “all men” 226 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val ont > *valon > valun “man hand > some men” 227 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for certain _# Cs, e.g. voiced stops, laterals, voiceless non- coronals, etc. 228 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for monosyllabic words— especially -

Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun Entries – Chapter 3, LFCA Example

Session A3: Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun entries – Chapter 3, LFCA When a Latin noun is listed in a dictionary it provides three pieces of information: The nominative singular, the genitive singular, and the gender. The first form, called nominative (from Latin nömen, name) is the means used to list, or name, words in a dictionary. The second form, the genitive (from Latin genus, origin, kind or family), is used to find the stem of the noun and to determine the declension, or noun family to which it belongs. To find the stem of a noun, simply look at the genitive singular form and remove the ending –ae. The final abbreviation is a reference to the noun’s gender, since it is not always evident by the noun’s endings. Example: fëmina, fëminae, f. woman stem = fëmin/ae 2. Declensions – Chapters 3 – 10, LFCA Just as verbs are divided up into families or groups called conjugations, so also nouns are divided up into groups that share similar characteristics and behavior patterns. A declension is a group of nouns that share a common set of inflected endings, which we call case endings (more on case later). The genitive reveals the declension or family of nouns from which a word originates. Just as the infinitive is different for each conjugation, the genitive singular is unique to each declension. 1 st declension mënsa, mënsae 2 nd declension lüdus, lüdï ager, agrï dönum, dönï 3 rd declension vöx, vöcis nübës, nübis corpus, corporis 4 th declension adventus, adventüs cornü, cornüs 5 th declension fidës, fideï Practice: 1. -

Nouns the Third Declension Is Generally Considered to Be A

CHAPTER 7 Third Declension : Nouns The third declension is generally considered to be a "pons asinorum" of Latin grammar. But I disagree. The third declension, aside for presenting you a new list of case endings to memorize, really involves no new grammatical principles you've haven't already been working with. I'll take you through it slowly, but most of this guide is actually going to be review. CASE ENDINGS The third declension has nouns of all three genders in it. Unlike the first and second declensions, where the majority of nouns are either feminine or masculine, the genders of the third declension are equally divided. So you really must pay attention to the gender markings in the dictionary entries for third declension nouns. The case endings for masculine and feminine nouns are identical. The case endings for neuter nouns are also of the same type as the feminine and masculine nouns, except for where neuter nouns follow their peculiar rules: (1) the nominative and the accusative forms are always the same, and (2) the nominative and accusative plural case endings are short "-a-". You may remember that the second declension neuter nouns have forms that are almost the same as the masculine nouns - except for these two rules. In other words, there is really only one pattern of endings for third declension nouns, whether the nouns are masculine, feminine, or neuter. It's just that neuter nouns have a peculiarity about them. So here are the third declension case endings. Notice that the separate column for neuter nouns is not really necessary, if you remember the rules of neuter nouns. -

Olga Tribulato Ancient Greek Verb-Initial Compounds

Olga Tribulato Ancient Greek Verb-Initial Compounds Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS Olga Tribulato Ancient Greek Verb-Initial Compounds Their Diachronic Development Within the Greek Compound System Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS ISBN 978-3-11-041576-6 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041582-7 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041586-5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Umschlagabbildung: Paul Klee: Einst dem Grau der Nacht enttaucht …, 1918, 17. Aquarell, Feder und Bleistit auf Papier auf Karton. 22,6 x 15,8 cm. Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern. Typesetting: Dr. Rainer Ostermann, München Printing: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS This book is for Arturo, who has waited so long. Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS Preface and Acknowledgements Preface and Acknowledgements I have always been ὀψιανθής, a ‘late-bloomer’, and this book is a testament to it. -

An Introduction to the Knowledge of Greek Grammar

AN * INTRODUCTION TO THE KNOWLEDGE or GREEK GRAMMAR. By SAMUEL B. WYLIE, D. D. IN THE WICE PROVOST AND PROFESSOR of ANCIENT LANGUAGES UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA. *NWTIET 16). <e) - \ 3} f) iſ a t t I pi} f a, J. whet HAM, 144 CHES NUT STREET. 1838. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1838, by SAMUEL B. Wylie, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. ANDov ER, MAss. Gould & Newman, Printers. **'. … Tº Co PR E FA C E. CoNSIDERING the number of Greek Grammars, already in market, some apology may appear necessary for the introduction of a new one. Without formally making a defence, it may be remarked, that subjects of deep interest, need to be viewed in as many different bearings as can readily be obtained. Grammar, whether considered as a branch of philological science, or a system of rules subservient to accuracy in speaking or writing any language, embraces a most interesting field of research, as wide and unlimited, as the progres sive development of the human mind. A work of such magnitude, requires a great variety of laborers, and even the humblest may be of some service. Even erroneous positions may be turned to good account, should they, by their refutation, contribute to the elucida tion of principle. A desire of obtaining a more compendious and systematic view of grammatical principles, and more adapted to his own taste in order and arrangement, induced the author to undertake, and gov erned him in the compilation of this manual. -

Adjective in Old English

Adjective in Old English Adjective in Old English had five grammatical categories: three dependent grammatical categories, i.e forms of agreement of the adjective with the noun it modified – number, gender and case; definiteness – indefiniteness and degrees of comparison. Adjectives had three genders and two numbers. The category of case in adjectives differed from that of nouns: in addition to the four cases of nouns they had one more case, Instrumental. It was used when the adjective served as an attribute to a noun in the Dat. case expressing an instrumental meaning. Weak and Strong Declension Most adjectives in OE could be declined in two ways: according to the weak and to the strong declension. The formal differences between the declensions, as well as their origin, were similar to those of the noun declensions. The strong and weak declensions arose due to the use of several stem-forming suffixes in PG: vocalic a-, o-, u- and i- and consonantal n-. Accordingly, there developed sets of endings of the strong declension mainly coinciding with the endings of a-stems of nouns for adjectives in the Masc. and Neut. and of o-stems – in the Fem. Some endings in the strong declension of adjectives have no parallels in the noun paradigms; they are similar to the endings of pronouns: -um for Dat. sg, -ne for Acc. Sg Masc., [r] in some Fem. and pl endings. Therefore the strong declension of adjectives is sometimes called the ‘pronominal’ declension. As for the weak declension, it uses the same markers as n-stems of nouns except that in the Gen. -

Early Christian Thought

The RouTledge Companion To eaRly ChRisTian ThoughT The shape and course which Christian thought has taken over its history is largely due to the contributions of individuals and communities in the second and third centuries. Bringing together a remarkable team of distinguished scholars, The Routledge Companion to Early Christian Thought is the ideal companion for those seeking to understand the way in which early Christian thought developed within its broader cultural milieu and was communicated through its literature, especially as it was directed toward theological concerns. divided into three parts, the Companion: • asks how Christianity’s development was impacted by its interaction with cultural, philosophical, and religious elements within the broader context of the second and third centuries; • examines the way in which early Christian thought was manifest in key individuals and literature in these centuries; • analyses early Christian thought as it was directed toward theological concerns such as god, Christ, redemption, scripture, and the community and its worship. D. Jeffrey Bingham is department Chair and professor of Theological studies at dallas Theological seminary, usa. he is editor of the Brill monograph series, The Bible in Ancient Christianity, as well as author of Irenaeus’ Use of Matthew’s Gospel in Adversus Haereses and several articles and essays on the theology and biblical inter- pretation of early Christianity. The RouTledge Companion To eaRly ChRisTian ThoughT Edited by D. Jeffrey Bingham First published 2010 by Routledge 2 park square, milton park, abingdon, oxon oX14 4Rn simultaneously published in the usa and Canada by Routledge 270 madison ave., new york, ny 100016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2010. -

Andra Kalnača a Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar

Andra Kalnača A Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar Andra Kalnača A Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar Managing Editor: Anna Borowska Associate Editor: Helle Metslang Language Editor: Uldis Balodis Published by De Gruyter Open Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Munich/Boston This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 license, which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. Copyright © 2014 Andra Kalnača ISBN 978-3-11-041130-0 e- ISBN 978-3-11-041131-7 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Managing Editor: Anna Borowska Associate Editor: Helle Metslang Language Editor: Uldis Balodis www.degruyteropen.com Cover illustration: © Ieva Kalnača Contents Abbreviations I Introduction II 1 The Paradigmatics and Declension of Nouns 1 1.1 Introductory Remarks on Paradigmatics 1 1.2 Declension 4 1.2.1 Noun Forms and Palatalization 9 1.2.2 Nondeclinable Nouns 11 1.3 Case Syncretism 14 1.3.1 Instrumental 18 1.3.2 Vocative 25 1.4 Reflexive Nouns 34 1.5 Case Polyfunctionality and Case Alternation 47 1.6 Gender 66 2 The Paradigmatics and Conjugation of Verbs 74 2.1 Introductory Remarks 74 2.2 Conjugation 75 2.3 Tense 80 2.4 Person 83 3 Aspect 89