Humanitarian Overview of Five Hard-To-Reach Areas in Iraq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Formula in the Battle for Fallujah | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds A New Formula in the Battle for Fallujah by Michael Knights May 25, 2016 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Michael Knights Michael Knights is the Boston-based Jill and Jay Bernstein Fellow of The Washington Institute, specializing in the military and security affairs of Iraq, Iran, and the Persian Gulf states. Articles & Testimony The campaign is Iraq's latest attempt to push militia and coalition forces into a single battlespace, and lessons from past efforts have seemingly improved their tactics. n May 22, the Iraqi government announced the opening of the long-awaited battle of Fallujah, the city only O 30 miles west of Baghdad that has been fully under the control of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant group for the past 29 months. Fallujah was a critical hub for al-Qaeda in Iraq and later ISIL in the decade before ISIL's January 2014 takeover. On the one hand it may seem surprising that Fallujah has not been liberated sooner -- after all, it has been the ISIL- controlled city closest to Baghdad for more than two years. The initial reason was that there was always something more urgent to do with Iraq's security forces. In January 2014, the Iraqi security forces were focused on preventing an ISIL takeover of Ramadi next door. The effort to retake Fallujah was judged to require detailed planning, and a hasty counterattack seemed like a pointless risk. In retrospect it may have been worth an early attempt to break up ISIL's control of the city while it was still incomplete. -

Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq

HUMAN RIGHTS UNAMI Office of the United Nations United Nations Assistance Mission High Commissioner for for Iraq – Human Rights Office Human Rights Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq: 11 December 2014 – 30 April 2015 “The United Nations has serious concerns about the thousands of civilians, including women and children, who remain captive by ISIL or remain in areas under the control of ISIL or where armed conflict is taking place. I am particularly concerned about the toll that acts of terrorism continue to take on ordinary Iraqi people. Iraq, and the international community must do more to ensure that the victims of these violations are given appropriate care and protection - and that any individual who has perpetrated crimes or violations is held accountable according to law.” − Mr. Ján Kubiš Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General in Iraq, 12 June 2015, Baghdad “Civilians continue to be the primary victims of the ongoing armed conflict in Iraq - and are being subjected to human rights violations and abuses on a daily basis, particularly at the hands of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Ensuring accountability for these crimes and violations will be paramount if the Government is to ensure justice for the victims and is to restore trust between communities. It is also important to send a clear message that crimes such as these will not go unpunished’’ - Mr. Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 12 June 2015, Geneva Contents Summary ...................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

1 Month of October in the City of Samarra by Themselves. They 2 Had the Most Contacts of Any Platoon in the Entire Battalion 3 and They Suffered No Casualties

1 month of October in the city of Samarra by themselves. They 2 had the most contacts of any platoon in the entire battalion 3 and they suffered no casualties. There is no other platoon in 4 the battalion that can say that. He set up the first police 5 station in Balad and trained and monitored the Iraqis. 6 7 Balad was the geopolitical center of that region. It was 8 very unstable at the time and one of the hottest spots in Iraq. 9 Within a month we owned the city and built great relationships. 10 Subsequently, we spent a lot of money improving the 11 infrastructure. The periphery was mostly Sunni. Trying to 12 bring them into the government was difficult, but once we 13 controlled Balad and the city outlines, we controlled the 14 entire region. 15 16 Lieutenant Saville's platoon were the key to the success for 17 Alpha Company. He was put in for two bronze stars. His 18 rehabilitative potential is very high. He's very mature. He's 19 a faith-filled man, outstanding leader, outstanding officer and 20 he's earned the faith of his men. He's combat tested and he's 21 a man of integrity. I would take him anywhere, anytime. I'd 22 go to combat with him, I'.d stand by his side and I'd put my son 23 in his outfit if we were going back to war without thought. 24 25 CROSS-EXAMINATION 26 27 Questions by the trial counsel-Captain Schiffer: 28 29 The platoons were very autonomous because of the lack of 30 leadership in 1-66 Armor. -

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq Julie Ahn—Maeve Campbell—Pete Knoetgen Client: Office of Iraq Affairs, U.S. Department of State Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Advisor: Meghan O’Sullivan Policy Analysis Exercise Seminar Leader: Matthew Bunn May 7, 2018 This Policy Analysis Exercise reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing the views of the US Government, nor those of Harvard University or any of its faculty. Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to the many people who helped us throughout the development, research, and drafting of this report. Our field work in Iraq would not have been possible without the help of Sherzad Khidhir. His willingness to connect us with in-country stakeholders significantly contributed to the breadth of our interviews. Those interviews were made possible by our fantastic translators, Lezan, Ehsan, and Younis, who ensured that we could capture critical information and the nuance of discussions. We also greatly appreciated the willingness of U.S. State Department officials, the soldiers of Operation Inherent Resolve, and our many other interview participants to provide us with their time and insights. Thanks to their assistance, we were able to gain a better grasp of this immensely complex topic. Throughout our research, we benefitted from consultations with numerous Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) faculty, as well as with individuals from the larger Harvard community. We would especially like to thank Harvard Business School Professor Kristin Fabbe and Razzaq al-Saiedi from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative who both provided critical support to our project. -

Kirkuk and Its Arabization: Historical Background and Ongoing Issues In

Abstract The Arabization of the Kurdistan region in Iraq Since the establishment of the Iraqi state, the ruling Arab regimes forcibly displaced native Kurds and repopulated the area with Arab tribes. The change of demography,known as “Arabization,” existed in both Kurdish majority agriculture and urban lands. These policies were part of a larger Iraqi campaign to erase the Kurdish identity, occupy Kurdistan, and control its wealth. The Iraqi government’s campaign against the Kurds amounted to genocide and eventually destroyed Kurdish communities and the social fabric of Kurdistan. The areas affected by the Arabization stretch from eastern to northwestern Iraq , incorporating major cities,towns, and hundreds of villages. After the fall of Saddam Hussien’s dictatorship, these areas became referred to as “Disputed Territories'' in Iraq’s newly adopted constitution of 2005. Article 140 of Iraq’s constitution called for the normalization of the “Disputed Territories,” which was never implemented by the federal government of Iraq. 1 www.dckurd.org Kirkuk province, Khanagin city of Diyala province, Tuz Khurmatu District of Saladin Province, and Shingal (Sinjar) in Nineveh province are the main areas that continue to suffer from Arabization policies implemented in 1975. KIRKUK A key feature of Kirkuk is its diversity – Kurds, Arabs, Turkmens, Shiites, Sunnis, and Christians (Chaldeans and Assyrians) all co-exist in Kirkuk, and the province is even home to a small Armenian Christian population. GEOGRAPHY The province of Kirkuk has a population of more than 1.4 million, the overwhelming majority of whom live in Kirkuk city. Kirkuk city is 160 miles north of Baghdad and just 60 miles from Erbil, the capital of the Iraqi Kurdistan region. -

Can Iraq's Army Dislodge the Islamic State? | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds Can Iraq's Army Dislodge the Islamic State? by Michael Knights Mar 4, 2015 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Michael Knights Michael Knights is the Boston-based Jill and Jay Bernstein Fellow of The Washington Institute, specializing in the military and security affairs of Iraq, Iran, and the Persian Gulf states. Articles & Testimony The just-launched Tikrit operation raises question about the relative exclusion of coalition support, the prominence of Shiite militias, the degree of Iranian involvement, and the Iraqi army's readiness for a much more imposing campaign in Mosul. n 1 March about 27,000 Iraqi troops commenced their attack on Tikrit, a city 150km (93 miles) north of O Baghdad that has been occupied by the Islamic State (IS) since June 2014. The assault is the first attempt to evict IS from a major urban centre that they have controlled and fortified, a test case for the planned operation to retake Mosul -- the Iraqi capital of the IS caliphate. The Tikrit operation will be scrutinised to shed light on two main uncertainties. Can predominately Shia volunteer forces play a productive leading role in operations within Sunni communities? And can the Iraqi military dislodge IS defenders from fortified urban settings? IRANIAN INPUT T he assault has been billed as a joint operation involving the Iraqi army, the paramilitary federal police, the Iraqi Special Operations Forces (ISOF), and the predominately Shia Popular Mobilisation Units (PMUs), the volunteer brigades and militias that have been formally integrated into the security forces since June 2014. -

MPLS VPN Service

MPLS VPN Service PCCW Global’s MPLS VPN Service provides reliable and secure access to your network from anywhere in the world. This technology-independent solution enables you to handle a multitude of tasks ranging from mission-critical Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP), Customer Relationship Management (CRM), quality videoconferencing and Voice-over-IP (VoIP) to convenient email and web-based applications while addressing traditional network problems relating to speed, scalability, Quality of Service (QoS) management and traffic engineering. MPLS VPN enables routers to tag and forward incoming packets based on their class of service specification and allows you to run voice communications, video, and IT applications separately via a single connection and create faster and smoother pathways by simplifying traffic flow. Independent of other VPNs, your network enjoys a level of security equivalent to that provided by frame relay and ATM. Network diagram Database Customer Portal 24/7 online customer portal CE Router Voice Voice Regional LAN Headquarters Headquarters Data LAN Data LAN Country A LAN Country B PE CE Customer Router Service Portal PE Router Router • Router report IPSec • Traffic report Backup • QoS report PCCW Global • Application report MPLS Core Network Internet IPSec MPLS Gateway Partner Network PE Router CE Remote Router Site Access PE Router Voice CE Voice LAN Router Branch Office CE Data Branch Router Office LAN Country D Data LAN Country C Key benefits to your business n A fully-scalable solution requiring minimal investment -

In the Shadow of a Massacre, a Peaceful Return in Iraq USIP Partners Ease Tensions Over 2014 Slaughter by Islamic State

In the Shadow of a Massacre, a Peaceful Return in Iraq USIP Partners Ease Tensions Over 2014 Slaughter by Islamic State July 16, 2015 Part 1 By Viola Gienger In a plain-as-beige conference room at Baghdad’s Babylon Hotel, the anger flared among the 16 robed Iraqi tribal leaders. The men, after all, carried into the room the outrage and fear from one of the country’s deadliest atrocities in recent years – the execution-style slaying in June 2014 of an estimated 1,700 young Iraqi air force cadets and soldiers at a base known as Camp Speicher. The accusations flew across the conference table – that tribes in the area supported the rampage by the self-styled “Islamic State” extremist group, and even joined in the killings. At one point, one of the highest-ranking sheikhs charged up out of his seat to leave the room. It was clear that others would follow. That scene in a Baghdad hotel in late March represented perhaps the crescendo of tension in a series of meetings and negotiations “If you do not take care of since December, supported by the U.S. Institute of Peace to the tensions immediately, forestall a new cycle of killing. The talks were led by the Network the government and the of Iraqi Facilitators (NIF) and SANAD for Peacebuilding, Iraqi non- international community government organizations that were established with the will have limited leeway Institute’s support and whose members sometimes work at great personal risk. once this spirals into more violence.” – USIP Senior The Speicher discussions were part of a structured effort that had Program Officer Sarhang begun months earlier and continues today. -

Iraq Master List Report 114 January – February 2020

MASTER LIST REPORT 114 IRAQ MASTER LIST REPORT 114 JANUARY – FEBRUARY 2020 HIGHLIGHTS IDP individuals 4,660,404 Returnee individuals 4,211,982 4,596,450 3,511,602 3,343,776 3,030,006 2,536,734 2,317,698 1,744,980 1,495,962 1,399,170 557,400 1,414,632 443,124 116,850 Apr Jun Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr June Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr June Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr June Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr June Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr June Aug Oct Dec Feb 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Figure 1. Number of IDPs and returnees over time Data collection for Round 114 took place during the months of January were secondary, with 5,910 individuals moving between locations of and February 2020. As of 29 February 2020, DTM identified 4,660,404 displacement, including 228 individuals who arrived from camps and 2,046 returnees (776,734 households) across 8 governorates, 38 districts and individuals who were re-displaced after returning. 2,574 individuals were 1,956 locations. An additional 63,954 returnees were recorded during displaced from their areas of origin for the first time. Most of them fled data collection for Report 114, which is significantly lower than the from Baghdad and Diyala governorates due to ongoing demonstrations, number of new returnees in the previous round (135,642 new returnees the worsening security situation, lack of services and lack of employment in Report 113). Most returned to the governorates of Anbar (26,016), opportunities. Ninewa (19,404) and Salah al-Din (5,754). -

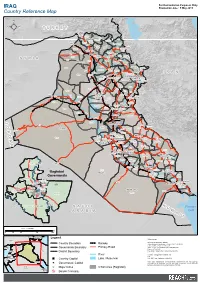

Country Reference Map

For Humanitarian Purposes Only IRAQ Production date : 5 May 2015 Country Reference Map T U R K E Y Ibrahim Al-Khalil (Habour) Zakho Zakho Amedi Dahuk Amedi Mergasur Dahuk Sumel Dahuk Rabia Mergasur Soran Sumel Shikhan Akre Haji Omaran Shikhan Akre Soran Telafar Choman Tilkaif Tilkaif Choman Shaqlawa Telafar Shaqlawa Sinjar Mosul Hamdaniya Rania Pshdar Sinjar Hamdaniya Erbil Ranya Qalat Erbil Dizah SYRIA Ba'aj Koisnjaq Mosul Erbil Ninewa Koisnjaq Dokan Baneh Dokan Makhmur Sharbazher Ba'aj Chwarta Penjwin Dabes Makhmur Penjwin Hatra Dabes Kirkuk Sulaymaniyah Chamchamal Shirqat Kirkuk IRAN Sulaymaniyah Hatra Shirqat Hawiga Daquq Sulaymaniyah Kirkuk Halabja Hawiga Chamchamal Darbandihkan Daquq Halabja Halabja Darbandikhan Baiji Tooz Khourmato Kalar Tikrit Baiji Tooz Ru'ua Kifri Kalar Tikrit Ru'ua Ka'im Salah Daur Kifri Ka'im Ana Haditha Munthiriya al-Din Daur Khanaqin Samarra Samarra Ka'im Haditha Khanaqin Balad Khalis Diyala Thethar Muqdadiya Balad Ana Al-Dujayl Khalis Muqdadiya Ba`aqubah Mandali Fares Heet Heet Ba'quba Baladrooz Ramadi Falluja Baghdad J Ramadi Rutba Baghdad Badra O Baramadad Falluja Badra Anbar Suwaira Azezia Turaybil Azezia R Musayab Suwaira Musayab D Ain Mahawil Al-Tamur Kerbala Mahawil Wassit Rutba Hindiya Na'miya Kut Ali Kerbala Kut Al-Gharbi A Ain BabylonHilla Al-Tamur Hindiya Ali Hashimiya Na'maniya Al-Gharbi Hashimiya N Kerbala Hilla Diwaniya Hai Hai Kufa Afaq Kufa Diwaniya Amara Najaf Shamiya Afaq Manathera Amara Manathera Qadissiya Hamza Rifa'i Missan Shamiya Rifa'i Maimouna Kahla Mejar Kahla Al-Kabi Qal'at Hamza -

Zakho Days: Travels with the General

NOT FOR PUBLICATION WITHOUT WRITER'S CONSENT INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS tog-7 Peter Byrd Martin I CWA Crane Rogers /+ %lest 4hee Iock Street Hanover NH June 26th 1991 Dear Peter, Here is an excerpt from my journeys in Kurdistan, an unfinished piece I submit to you without further comment, entitled: by Thomas Go ltz We first met in the Baghdad Hotel, the shabby new home away from home I had arranged for the staff of the International Rescue Committee in Zakho, northern Iraq. "This is Kek Aziz," my newly appointed manager, Mister Shukri, bashfully informed me, "He is my oldest and dearest friend, and he needs a shower." The stocky, older man was dressed in baggy shaar pants, a khaki shirt and wore a skull cap and when he opened his mouth to speak he revealed an upper jaw devoid of teeth. "Hello," he said, clicking his feet together in some manner of military salute while extending his hand, "I have not bathed in three weeks." It was only my second night as the director of the hotel, and was more than a little hesitant about letting in an aging .Peer.gah into my showers. A down-town dump, the Baghdad consisted of thirteen rooms and a roof, and prior to my taking possession it had served as the barracks for the last Iraqi troops in the city before they had withdrawn, surrendering the Zakho to the Americans. And in leaving, they seemed to have wanted to make it as uncomfortable as possible for any future tenants. The place had been trashed--curtains ripped, mattresses defiled, windows smashed. -

Salah Al Din Governorate,Iraq

SALAH AL DIN GOVERNORATE, IRAQ INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT FACTSHEET ATA COLLECTED EPTEMBER D : 8 – 15 S 2014 ISPLACEMENT VERVIEW D O IDPs in Salah Al Din were primarily relocated from Anbar, where fighting has been rife since The worsening security situation in parts of northern and central Iraq has caused mass the start of 2014. Many people fled from Falluja and Ramadi Districts to Salah Al Din internal displacement across much of the country. Humanitarian response operations because of its close proximity and comparative safety prior to June 2014. Since June 2014, have been taking place in the accessible areas of the north where approximately half of increased activity by Armed Opposition Groups (AOGs) within Salah Al Din has caused the 1.8 million Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) have currently settled. Elsewhere in further displacement, both within Salah Al Din and into neighbouring governorates. the country however, where security issues have imposed access constraints, information is incomplete and assistance is limited, leaving the remaining half of the Map 1: Districts included in the Salah Al Din governorate analysis displaced population without support from the humanitarian sector. In response to these information gaps, REACH Initiative set up and is using a network of key informants originating from inaccessible or hard-to-reach areas to assess the current situation in order to inform a rapid, targeted humanitarian response in these areas, as soon as they become accessible. This factsheet provides an overview of displacement trends from and to IDPs’ areas of origin, as well as key issues related to shelter, food and livelihoods faced by IDPs and communities living in areas affected by the crisis, followed by priority needs as identified during the assessment.