Zakho Days: Travels with the General

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Formula in the Battle for Fallujah | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds A New Formula in the Battle for Fallujah by Michael Knights May 25, 2016 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Michael Knights Michael Knights is the Boston-based Jill and Jay Bernstein Fellow of The Washington Institute, specializing in the military and security affairs of Iraq, Iran, and the Persian Gulf states. Articles & Testimony The campaign is Iraq's latest attempt to push militia and coalition forces into a single battlespace, and lessons from past efforts have seemingly improved their tactics. n May 22, the Iraqi government announced the opening of the long-awaited battle of Fallujah, the city only O 30 miles west of Baghdad that has been fully under the control of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant group for the past 29 months. Fallujah was a critical hub for al-Qaeda in Iraq and later ISIL in the decade before ISIL's January 2014 takeover. On the one hand it may seem surprising that Fallujah has not been liberated sooner -- after all, it has been the ISIL- controlled city closest to Baghdad for more than two years. The initial reason was that there was always something more urgent to do with Iraq's security forces. In January 2014, the Iraqi security forces were focused on preventing an ISIL takeover of Ramadi next door. The effort to retake Fallujah was judged to require detailed planning, and a hasty counterattack seemed like a pointless risk. In retrospect it may have been worth an early attempt to break up ISIL's control of the city while it was still incomplete. -

Humanitarian Overview of Five Hard-To-Reach Areas in Iraq

Humanitarian Overview of Five Hard-to-Reach Areas in Iraq IRAQ DECEMBER 2016 Table of Contents Methodology...................................................................................... 2 Summary ........................................................................................... 3 Humanitarian Overview Factsheets Falluja City .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Ramadi City......................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Heet City ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 9 Tikrit City ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 12 Muqdadiya City and surrounding villages ...................................................................................................................................... 15 Annex Severity matrix guide 18 Methodology Since January 2015 , REACH has been regularly collecting data to inform humanitarian planning in hard-to-reach areas across Iraq. As multiple hard-to-reach areas are no longer under Armed Group (AG) control -

Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq

HUMAN RIGHTS UNAMI Office of the United Nations United Nations Assistance Mission High Commissioner for for Iraq – Human Rights Office Human Rights Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq: 11 December 2014 – 30 April 2015 “The United Nations has serious concerns about the thousands of civilians, including women and children, who remain captive by ISIL or remain in areas under the control of ISIL or where armed conflict is taking place. I am particularly concerned about the toll that acts of terrorism continue to take on ordinary Iraqi people. Iraq, and the international community must do more to ensure that the victims of these violations are given appropriate care and protection - and that any individual who has perpetrated crimes or violations is held accountable according to law.” − Mr. Ján Kubiš Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General in Iraq, 12 June 2015, Baghdad “Civilians continue to be the primary victims of the ongoing armed conflict in Iraq - and are being subjected to human rights violations and abuses on a daily basis, particularly at the hands of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Ensuring accountability for these crimes and violations will be paramount if the Government is to ensure justice for the victims and is to restore trust between communities. It is also important to send a clear message that crimes such as these will not go unpunished’’ - Mr. Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 12 June 2015, Geneva Contents Summary ...................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

1 Month of October in the City of Samarra by Themselves. They 2 Had the Most Contacts of Any Platoon in the Entire Battalion 3 and They Suffered No Casualties

1 month of October in the city of Samarra by themselves. They 2 had the most contacts of any platoon in the entire battalion 3 and they suffered no casualties. There is no other platoon in 4 the battalion that can say that. He set up the first police 5 station in Balad and trained and monitored the Iraqis. 6 7 Balad was the geopolitical center of that region. It was 8 very unstable at the time and one of the hottest spots in Iraq. 9 Within a month we owned the city and built great relationships. 10 Subsequently, we spent a lot of money improving the 11 infrastructure. The periphery was mostly Sunni. Trying to 12 bring them into the government was difficult, but once we 13 controlled Balad and the city outlines, we controlled the 14 entire region. 15 16 Lieutenant Saville's platoon were the key to the success for 17 Alpha Company. He was put in for two bronze stars. His 18 rehabilitative potential is very high. He's very mature. He's 19 a faith-filled man, outstanding leader, outstanding officer and 20 he's earned the faith of his men. He's combat tested and he's 21 a man of integrity. I would take him anywhere, anytime. I'd 22 go to combat with him, I'.d stand by his side and I'd put my son 23 in his outfit if we were going back to war without thought. 24 25 CROSS-EXAMINATION 26 27 Questions by the trial counsel-Captain Schiffer: 28 29 The platoons were very autonomous because of the lack of 30 leadership in 1-66 Armor. -

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq Julie Ahn—Maeve Campbell—Pete Knoetgen Client: Office of Iraq Affairs, U.S. Department of State Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Advisor: Meghan O’Sullivan Policy Analysis Exercise Seminar Leader: Matthew Bunn May 7, 2018 This Policy Analysis Exercise reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing the views of the US Government, nor those of Harvard University or any of its faculty. Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to the many people who helped us throughout the development, research, and drafting of this report. Our field work in Iraq would not have been possible without the help of Sherzad Khidhir. His willingness to connect us with in-country stakeholders significantly contributed to the breadth of our interviews. Those interviews were made possible by our fantastic translators, Lezan, Ehsan, and Younis, who ensured that we could capture critical information and the nuance of discussions. We also greatly appreciated the willingness of U.S. State Department officials, the soldiers of Operation Inherent Resolve, and our many other interview participants to provide us with their time and insights. Thanks to their assistance, we were able to gain a better grasp of this immensely complex topic. Throughout our research, we benefitted from consultations with numerous Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) faculty, as well as with individuals from the larger Harvard community. We would especially like to thank Harvard Business School Professor Kristin Fabbe and Razzaq al-Saiedi from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative who both provided critical support to our project. -

Kirkuk and Its Arabization: Historical Background and Ongoing Issues In

Abstract The Arabization of the Kurdistan region in Iraq Since the establishment of the Iraqi state, the ruling Arab regimes forcibly displaced native Kurds and repopulated the area with Arab tribes. The change of demography,known as “Arabization,” existed in both Kurdish majority agriculture and urban lands. These policies were part of a larger Iraqi campaign to erase the Kurdish identity, occupy Kurdistan, and control its wealth. The Iraqi government’s campaign against the Kurds amounted to genocide and eventually destroyed Kurdish communities and the social fabric of Kurdistan. The areas affected by the Arabization stretch from eastern to northwestern Iraq , incorporating major cities,towns, and hundreds of villages. After the fall of Saddam Hussien’s dictatorship, these areas became referred to as “Disputed Territories'' in Iraq’s newly adopted constitution of 2005. Article 140 of Iraq’s constitution called for the normalization of the “Disputed Territories,” which was never implemented by the federal government of Iraq. 1 www.dckurd.org Kirkuk province, Khanagin city of Diyala province, Tuz Khurmatu District of Saladin Province, and Shingal (Sinjar) in Nineveh province are the main areas that continue to suffer from Arabization policies implemented in 1975. KIRKUK A key feature of Kirkuk is its diversity – Kurds, Arabs, Turkmens, Shiites, Sunnis, and Christians (Chaldeans and Assyrians) all co-exist in Kirkuk, and the province is even home to a small Armenian Christian population. GEOGRAPHY The province of Kirkuk has a population of more than 1.4 million, the overwhelming majority of whom live in Kirkuk city. Kirkuk city is 160 miles north of Baghdad and just 60 miles from Erbil, the capital of the Iraqi Kurdistan region. -

Iraq Humanitarian Fund (IHF) 1St Standard Allocation 2020 Allocation Strategy (As of 13 May 2020)

Iraq Humanitarian Fund (IHF) 1st Standard Allocation 2020 Allocation Strategy (as of 13 May 2020) Summary Overview o This Allocation Strategy is issued by the Humanitarian Coordinator (HC), in consultation with the Clusters and Advisory Board (AB), to set the IHF funding priorities for the 1st Standard Allocation 2020. o A total amount of up to US$ 12 million is available for this allocation. This allocation strategy paper outlines the allocation priorities and rationale for the prioritization. o This allocation paper also provides strategic direction and a timeline for the allocation process. o The HC in discussion with the AB has set the Allocation criteria as follows; ✓ Only Out-of-camp and other underserved locations ✓ Focus on ICCG priority HRP activities to support COVID-19 Response ✓ Focus on areas of response facing marked resource mobilization challenges Allocation strategy and rationale Situation Overview As of 10 May 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) has confirmed 2,676 cases of COVID-19 in Iraq; 107 fatalities; and 1,702 patients who have recovered from the virus. The Government of Iraq (GOI) and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) have generally relaxed enforcement of the stringent curfews and movement restrictions which have been in place for several weeks, although they are nominally still applicable. Partial lockdowns are currently in force in federal Iraq until 22 May, and in Kurdistan Region of Iraq until 18 May. The WHO and the Ministry of Health recommend maintenance of strict protective measures for all citizens to prevent a resurgence of new cases in the country. The humanitarian community in Iraq is committed to both act now to stem the impact of COVID-19 by protecting those most at risk in already vulnerable humanitarian contexts and continue to support existing humanitarian response plans, in increasingly challenging environments. -

Can Iraq's Army Dislodge the Islamic State? | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds Can Iraq's Army Dislodge the Islamic State? by Michael Knights Mar 4, 2015 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Michael Knights Michael Knights is the Boston-based Jill and Jay Bernstein Fellow of The Washington Institute, specializing in the military and security affairs of Iraq, Iran, and the Persian Gulf states. Articles & Testimony The just-launched Tikrit operation raises question about the relative exclusion of coalition support, the prominence of Shiite militias, the degree of Iranian involvement, and the Iraqi army's readiness for a much more imposing campaign in Mosul. n 1 March about 27,000 Iraqi troops commenced their attack on Tikrit, a city 150km (93 miles) north of O Baghdad that has been occupied by the Islamic State (IS) since June 2014. The assault is the first attempt to evict IS from a major urban centre that they have controlled and fortified, a test case for the planned operation to retake Mosul -- the Iraqi capital of the IS caliphate. The Tikrit operation will be scrutinised to shed light on two main uncertainties. Can predominately Shia volunteer forces play a productive leading role in operations within Sunni communities? And can the Iraqi military dislodge IS defenders from fortified urban settings? IRANIAN INPUT T he assault has been billed as a joint operation involving the Iraqi army, the paramilitary federal police, the Iraqi Special Operations Forces (ISOF), and the predominately Shia Popular Mobilisation Units (PMUs), the volunteer brigades and militias that have been formally integrated into the security forces since June 2014. -

IDP and Refugee Camp Locations - As of January 2017

For Humanitarian Purposes Only IRAQ Production date: 01 February 2017 IDP and Refugee Camp Locations - As of January 2017 Za k ho T U R K E Y Darkar ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑⛳⚑Bersive II Chamishku Bersive I Dawudiya ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Am e di Bajet Kandala ² Rwanga Dahuk Community Me r ga s ur Da h uk Su m el So r an !PDahuk Kabrato I+II Ak r e Khanke ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Shariya S Y R I A ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Sh i kh a n Domiz I+II Essian Akre ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Sheikhan Amalla ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Garmawa ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑Mamrashan ⛳⚑ Mamilian ⛳⚑Nargizlia Ch o ma n 1 + 2 Tel af ar Ti lk a if Qaymawa ⛳⚑ Basirma ⛳⚑ Bardarash Darashakran ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Sh a ql a w a Si n ja r Hasansham M2 Gawilan Kawergosk Mosul!P ⛳⚑ I R A N Hasansham U3 ⛳⚑⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Baharka ⛳⚑ Ps h da r Ha m da n iy a Khazer M1 Ra n ia Harsham ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Erbil Ankawa 2 !P Erbil Mo s ul Ninewa Er b il Ko i sn j aq Qushtapa ⛳⚑ Do k an Debaga 1 ⛳⚑ Debaga 4 ⛳⚑⛳⚑ Surdesh Debaga Debaga 2 ⛳⚑ Stadium Ba 'a j Hasiyah ⛳⚑ Tina ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Qayyarah-Jad'ah Sh a rb a zh e r Pe n jw i n Ma k hm u r Ki r ku k Da b es Sulaymaniyah !P Barzinja Kirkuk ⛳⚑ Su l ay m an i y ah Ha t ra !P Arbat IDP ⛳⚑ Sh i rq a t ⛳⚑ Ashti IDP Nazrawa ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑Arbat Refugee Yahyawa ⛳⚑⛳⚑ Laylan 1 Sulaymaniyah Ha w ig a Kirkuk Da r ba n d ih k an Daquq ⛳⚑ Ch a mc h a ma l Laylan 2 ⛳⚑ Ha l ab j a Da q uq Ka l ar Hajjaj Camp ⛳⚑ Al-Alam ⛳⚑⛳⚑2 (MoMD) Ba i ji Al Alam 1 To oz (UNHCR) Tik r it Tazade ⛳⚑Al Safyh ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Tikrit Ru 'u a University Qoratu ⛳⚑ Al Obaidi Ki f ri ⛳⚑ Salah al-Din Da u r Ka 'i m Al Wand 1 Al Wand 2⛳⚑ Ha d it h a Sa m ar r a Al Abassia Al-Hawesh ⛳⚑ Kh a na q in ⛳⚑ !P Samarra Al-Iraq Al-Hardania Al-Muahad ⛳⚑ Diyala ⛳⚑ -

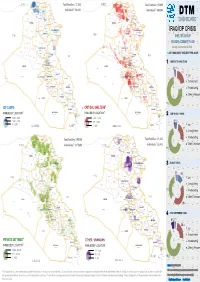

20141214 04 IOM DTM Repor

TURKEY Zakho Amedi Total Families: 27,209 TURKEY Zakho Amedi TURKEY Total Families: 113,999 DAHUK Mergasur DAHUK Mergasur Dahuk Sumel 1 Sumel Dahuk 1 Soran Individual : 163,254 Soran Individuals : 683,994 DTM Al-Shikhan Akre Al-Shikhan Akre Tel afar Choman Telafar Choman Tilkaif Tilkaif Shaqlawa Shaqlawa Al-Hamdaniya Rania Al-Hamdaniya Rania Sinjar Pshdar Sinjar Pshdar ERBIL ERBIL DASHBOARD Erbil Erbil Mosul Koisnjaq Mosul Koisnjaq NINEWA Dokan NINEWA Dokan Makhmur Sharbazher Penjwin Makhmur Sharbazher Penjwin Dabes Dabes IRAQ IDP CRISIS Al-Ba'aj SULAYMANIYAH Al-Ba'aj SULAYMANIYAH Hatra Al-Shirqat Kirkuk Hatra Al-Shirqat Kirkuk Sulaymaniya Sulaymaniya KIRKUK KIRKUK Al-Hawiga Chamchamal Al-Hawiga Chamchamal DarbandihkanHalabja SYRIA Darbandihkan SYRIA Daquq Daquq Halabja SHELTER GROUP Kalar Kalar Baiji Baiji Tooz Tooz BY DISPLACEMENT FLOW Ra'ua Tikrit SYRIA Ra'ua Tikrit Kifri Kifri January to December 9, 2014 SALAH AL-DIN Haditha Haditha SALAH AL-DIN Samarra Al-Daur Khanaqin Samarra Al-Daur Khanaqin Al-Ka'im Al-Ka'im Al-Thethar Al-Khalis Al-Thethar Al-Khalis % OF FAMILIES BY SHELTER TYPE AS OF: DIYALA DIYALA Ana Balad Ana Balad IRAN Al-Muqdadiya IRAN Al-Muqdadiya IRAN Heet Al-Fares Heet Al-Fares Tar m ia Tarm ia Ba'quba Ba'quba Adhamia Baladrooz Adhamia Baladrooz Kadhimia Kadhimia JANUARY TO MAY CRISIS KarkhAl Resafa Ramadi Ramadi KarkhAl Resafa 1 Abu Ghraib Abu Ghraib BAGHDADMada'in BAGHDADMada'in ANBAR Falluja ANBAR Falluja Mahmoudiya Mahmoudiya Badra Badra 2% 1% Al-Azezia Al-Azezia Al-Suwaira Al-Suwaira Al-Musayab Al-Musayab 21% Al-Mahawil -

MPLS VPN Service

MPLS VPN Service PCCW Global’s MPLS VPN Service provides reliable and secure access to your network from anywhere in the world. This technology-independent solution enables you to handle a multitude of tasks ranging from mission-critical Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP), Customer Relationship Management (CRM), quality videoconferencing and Voice-over-IP (VoIP) to convenient email and web-based applications while addressing traditional network problems relating to speed, scalability, Quality of Service (QoS) management and traffic engineering. MPLS VPN enables routers to tag and forward incoming packets based on their class of service specification and allows you to run voice communications, video, and IT applications separately via a single connection and create faster and smoother pathways by simplifying traffic flow. Independent of other VPNs, your network enjoys a level of security equivalent to that provided by frame relay and ATM. Network diagram Database Customer Portal 24/7 online customer portal CE Router Voice Voice Regional LAN Headquarters Headquarters Data LAN Data LAN Country A LAN Country B PE CE Customer Router Service Portal PE Router Router • Router report IPSec • Traffic report Backup • QoS report PCCW Global • Application report MPLS Core Network Internet IPSec MPLS Gateway Partner Network PE Router CE Remote Router Site Access PE Router Voice CE Voice LAN Router Branch Office CE Data Branch Router Office LAN Country D Data LAN Country C Key benefits to your business n A fully-scalable solution requiring minimal investment -

The Martyrs St

November 1st, 2015 1st Sunday of the Church SAINTS OF THE WEEK SPECIAL EDITION: THE MARTYRS ST. ISAAC OF NINEVEH Father Ragheed Ganni was a Chaldean priest who was studying at the Irish College when the US invaded Iraq. He asked his bishop for permission to return to be with his people, and afterwards, he had received many death threats. In 2007, after the evening liturgy in Mosul’s Holy Spirit Chaldean Church, Father Ragheed was leaving together with three subdeacons. His car was stopped by gun men, although he was smiling, laughing, and trying to He was born in the region of engage with them. They said they will teach him to Beth Qatraye in Eastern Arabia. laugh and cut him in half with machine gun fire. He When still quite young, he was martyred along with the three subdeacons. entered a monastery where he devoted his energies towards the At the time of this murder, Father Ragheed was practice of asceticism. After secretary to Paolos Faraj Rahho, the archbishop of many years of studying at the library attached to the Mosul. Bishop Rahho was murdered only nine monastery, he emerged as an months after Father Ragheed in the same city of authoritative figure in theology. Mosul. The Chaldean Church immediately mourned Shortly after, he dedicated his them as martyrs, and Pope Benedict XVI life to monasticism and became immediately prayed for them from Rome. involved in religious education throughout the Beth Qatraye Sister Cecilia had belonged to the Order of the region. When the Catholicos Sacred Heart of Jesus and had devoted her life to Georges (680–659) visited Beth ministering to the poor and ill.