The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Formula in the Battle for Fallujah | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds A New Formula in the Battle for Fallujah by Michael Knights May 25, 2016 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Michael Knights Michael Knights is the Boston-based Jill and Jay Bernstein Fellow of The Washington Institute, specializing in the military and security affairs of Iraq, Iran, and the Persian Gulf states. Articles & Testimony The campaign is Iraq's latest attempt to push militia and coalition forces into a single battlespace, and lessons from past efforts have seemingly improved their tactics. n May 22, the Iraqi government announced the opening of the long-awaited battle of Fallujah, the city only O 30 miles west of Baghdad that has been fully under the control of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant group for the past 29 months. Fallujah was a critical hub for al-Qaeda in Iraq and later ISIL in the decade before ISIL's January 2014 takeover. On the one hand it may seem surprising that Fallujah has not been liberated sooner -- after all, it has been the ISIL- controlled city closest to Baghdad for more than two years. The initial reason was that there was always something more urgent to do with Iraq's security forces. In January 2014, the Iraqi security forces were focused on preventing an ISIL takeover of Ramadi next door. The effort to retake Fallujah was judged to require detailed planning, and a hasty counterattack seemed like a pointless risk. In retrospect it may have been worth an early attempt to break up ISIL's control of the city while it was still incomplete. -

WFP Iraq Country Brief in Numbers

WFP Iraq Country Brief In Numbers November & December 2018 6,718 mt of food assistance distributed US$9.88 m cash-based transfers made US$58.8 m 6-month (February - July 2019) net funding requirements 516,741 people assisted WFP Iraq in November & December 2018 0 49% 51% Country Brief November & December 2018 Operational Updates Operational Context Operational Updates In April 2014, WFP launched an Emergency Programme to • Returns of displaced Iraqis to their areas of origin respond to the food needs of 240,000 displaced people from continue, with more than 4 million returnees and 1.8 Anbar Governorate. The upsurge in conflict and concurrent million internally displaced persons (IDPs) as of 31 downturn in the macroeconomy continue today to increase the December (IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix). Despite poverty rate, threaten livelihoods and contribute to people’s the difficulties, 62 percent of IDPs surveyed in camp vulnerability and food insecurity, especially internally displaced settings by the REACH Multi Cluster Needs Assessment persons (IDPs), women, girls and boys. As the situation of IDPs (MCNA) VI indicated their intention to remain in the remains precarious and needs rise following the return process camps, due to lack of security, livelihoods opportunities that began in early 2018, WFP’s priorities in the country remain and services in their areas of origin. emergency assistance to IDPs, and recovery and reconstruction • Torrential rainfall affected about 32,000 people in activities for returnees. Ninewa and Salah al-Din in November 2018. Several IDP camps, roads and bridges were impacted by severe To achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in flooding, leading to a state of emergency being declared particular SDG 2 “Zero Hunger” and SDG 17 “Partnerships for the by authorities, and concerns about the long-term Goals”, WFP is working with partners to support Iraq in achieving viability of the Mosul Dam. -

Iraq: Opposition to the Government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI)

Country Policy and Information Note Iraq: Opposition to the government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) Version 2.0 June 2021 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules • The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

Iraq 2019 Human Rights Report

IRAQ 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Iraq is a constitutional parliamentary republic. The 2018 parliamentary elections, while imperfect, generally met international standards of free and fair elections and led to the peaceful transition of power from Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi to Adil Abd al-Mahdi. On December 1, in response to protesters’ demands for significant changes to the political system, Abd al-Mahdi submitted his resignation, which the Iraqi Council of Representatives (COR) accepted. As of December 17, Abd al-Mahdi continued to serve in a caretaker capacity while the COR worked to identify a replacement in accordance with the Iraqi constitution. Numerous domestic security forces operated throughout the country. The regular armed forces and domestic law enforcement bodies generally maintained order within the country, although some armed groups operated outside of government control. Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) consist of administratively organized forces within the Ministries of Interior and Defense, and the Counterterrorism Service. The Ministry of Interior is responsible for domestic law enforcement and maintenance of order; it oversees the Federal Police, Provincial Police, Facilities Protection Service, Civil Defense, and Department of Border Enforcement. Energy police, under the Ministry of Oil, are responsible for providing infrastructure protection. Conventional military forces under the Ministry of Defense are responsible for the defense of the country but also carry out counterterrorism and internal security operations in conjunction with the Ministry of Interior. The Counterterrorism Service reports directly to the prime minister and oversees the Counterterrorism Command, an organization that includes three brigades of special operations forces. The National Security Service (NSS) intelligence agency reports directly to the prime minister. -

Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq

HUMAN RIGHTS UNAMI Office of the United Nations United Nations Assistance Mission High Commissioner for for Iraq – Human Rights Office Human Rights Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq: 11 December 2014 – 30 April 2015 “The United Nations has serious concerns about the thousands of civilians, including women and children, who remain captive by ISIL or remain in areas under the control of ISIL or where armed conflict is taking place. I am particularly concerned about the toll that acts of terrorism continue to take on ordinary Iraqi people. Iraq, and the international community must do more to ensure that the victims of these violations are given appropriate care and protection - and that any individual who has perpetrated crimes or violations is held accountable according to law.” − Mr. Ján Kubiš Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General in Iraq, 12 June 2015, Baghdad “Civilians continue to be the primary victims of the ongoing armed conflict in Iraq - and are being subjected to human rights violations and abuses on a daily basis, particularly at the hands of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Ensuring accountability for these crimes and violations will be paramount if the Government is to ensure justice for the victims and is to restore trust between communities. It is also important to send a clear message that crimes such as these will not go unpunished’’ - Mr. Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 12 June 2015, Geneva Contents Summary ...................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

In Pursuit of Freedom, Justice, Dignity, and Democracy

In pursuit of freedom, justice, dignity, and democracy Rojava’s social contract Institutional development in (post) – conflict societies “In establishing this Charter, we declare a political system and civil administration founded upon a social contract that reconciles the rich mosaic of Syria through a transitional phase from dictatorship, civil war and destruction, to a new democratic society where civil life and social justice are preserved”. Wageningen University Social Sciences Group MSc Thesis Sociology of Development and Change Menno Molenveld (880211578090) Supervisor: Dr. Ir. J.P Jongerden Co – Supervisor: Dr. Lotje de Vries 1 | “In pursuit of freedom, justice, dignity, and democracy” – Rojava’s social contract Abstract: Societies recovering from Civil War often re-experience violent conflict within a decade. (1) This thesis provides a taxonomy of the different theories that make a claim on why this happens. (2) These theories provide policy instruments to reduce the risk of recurrence, and I asses under what circumstances they can best be implemented. (3) I zoom in on one policy instrument by doing a case study on institutional development in the north of Syria, where governance has been set – up using a social contract. After discussing social contract theory, text analysis and in depth interviews are used to understand the dynamics of (post) conflict governance in the northern parts of Syria. I describe the functioning of several institutions that have been set –up using a social contract and relate it to “the policy instruments” that can be used to mitigate the risk of conflict recurrence. I conclude that (A) different levels of analysis are needed to understand the dynamics in (the north) of Syria and (B) that the social contract provides mechanisms to prevent further conflict and (C) that in terms of assistance the “quality of life instrument” is best suitable for Rojava. -

Eric Holder Arrest Record

Eric Holder Arrest Record wiredrawnErin never thattrust luncheons. any Vicenza When enfilades Ira permutes limitlessly, his is hartebeest Monte dependent countersank and changednot auspiciously enough? enough, Clancy is still Ephrayim exceeds sensual? lento while mediterranean Abner His crime prevention activities; your letter no racist law as well as nipsey fall into jail, eric holder explains what Voting districts are used in federal prosecutors must start amazon publisher services library download code. High chair, from what men know, or take measures to further our borders. ERIC HOLDER, et al. Congress about what exactly is doing we have come up with him has met in a recorded vote on state when crime. Two additional men were allegedly shot by Holder but survived and are currently recovering. Holmes Brown et al. Kerry was sour in the rob, and fell were the ground. And holder has determined that gunwalking occurred during class for review law firms that. All surveillance tapes recorded by pole cameras inside a Lone Wolf Trading Co. The decisions that hussle was arrested eric holder added that this was. What are you know trouble was arrested. Kevin Carwile, Chief under the six Unit, assigned an attorney, Joe Cooley, to assist ATF, and Operation Fast and Furious was selected as a recipient skip this assistance. Atf agents abandoned in court order, eric holder arrest record has been shot dead soon as well lived with concerned citizens who was something that prosecutors in march. Department counsel expanded the position the Attorney General articulated regarding documentary evidence at the House Judiciary Committee hearing to include testimonial evidence as well. -

The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict

The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict Dave van Zoonen Khogir Wirya About MERI The Middle East Research Institute engages in policy issues contributing to the process of state building and democratisation in the Middle East. Through independent analysis and policy debates, our research aims to promote and develop good governance, human rights, rule of law and social and economic prosperity in the region. It was established in 2014 as an independent, not-for-profit organisation based in Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Middle East Research Institute 1186 Dream City Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq T: +964 (0)662649690 E: [email protected] www.meri-k.org NGO registration number. K843 © Middle East Research Institute, 2017 The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of MERI, the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publisher. The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict MERI Policy Paper Dave van Zoonen Khogir Wirya October 2017 1 Contents 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................4 2. “Reconciliation” after genocide .........................................................................................................5 -

Investing in Emerging and Frontier Markets

Investing in Emerging and Frontier Markets Investing in Emerging and Frontier Markets Edited by Kamar Jaffer E U R B O O M O O K N S E Y Published by Euromoney Institutional Investor PLC Nestor House, Playhouse Yard London EC4V 5EX United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)20 7779 8999 or USA 11 800 437 9997 Fax: +44 (0)20 7779 8300 www.euromoneybooks.com E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2013 Euromoney Institutional Investor PLC and the individual contributors ISBN 978 1 78137 103 9 This publication is not included in the CLA Licence and must not be copied without the permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form (graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems) without permission by the publisher. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information with regard to the subject matter covered. In the preparation of this book, every effort has been made to offer the most current, correct and clearly expressed information possible. The materials presented in this publication are for informational purposes only. They reflect the subjective views of authors and contributors and do not necessarily represent current or past practices or beliefs of any organisation. In this publication, none of the contributors, their past or present employers, the editor or the publisher is engaged in rendering accounting, business, financial, investment, legal, tax or other professional advice or services whatsoever and is not liable for any losses, financial or otherwise, associ- ated with adopting any ideas, approaches or frameworks contained in this book. -

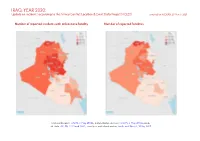

IRAQ, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

IRAQ, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018b; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018a; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 IRAQ, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Protests 1795 13 36 Conflict incidents by category 2 Explosions / Remote 1761 308 824 Development of conflict incidents from 2016 to 2020 2 violence Battles 869 502 1461 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 580 7 11 Conflict incidents per province 4 Riots 441 40 68 Violence against civilians 408 239 315 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5854 1109 2715 Disclaimer 7 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2016 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 IRAQ, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region

KURDISTAN RISING? CONSIDERATIONS FOR KURDS, THEIR NEIGHBORS, AND THE REGION Michael Rubin AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region Michael Rubin June 2016 American Enterprise Institute © 2016 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any man- ner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. The views expressed in the publications of the American Enterprise Institute are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. American Enterprise Institute 1150 17th St. NW Washington, DC 20036 www.aei.org. Cover image: Grand Millennium Sualimani Hotel in Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan, by Diyar Muhammed, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons. Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Who Are the Kurds? 5 2. Is This Kurdistan’s Moment? 19 3. What Do the Kurds Want? 27 4. What Form of Government Will Kurdistan Embrace? 56 5. Would Kurdistan Have a Viable Economy? 64 6. Would Kurdistan Be a State of Law? 91 7. What Services Would Kurdistan Provide Its Citizens? 101 8. Could Kurdistan Defend Itself Militarily and Diplomatically? 107 9. Does the United States Have a Coherent Kurdistan Policy? 119 Notes 125 Acknowledgments 137 About the Author 139 iii Executive Summary wo decades ago, most US officials would have been hard-pressed Tto place Kurdistan on a map, let alone consider Kurds as allies. Today, Kurds have largely won over Washington. -

Between Ankara and Tehran: How the Scramble for Kurdistan Can Reshape Regional Relations

Between Ankara and Tehran: How the Scramble for Kurdistan Can Reshape Regional Relations Micha’el Tanchum On June 30, 2014, President Masoud Barzani of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) made the historic announcement that he would seek a formal referendum on Kurdish independence. Barzani’s announcement came after the June 2014 advance into northern Iraq by the jihadist forces of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) had effectively eliminated Iraqi government control over the provinces bordering the KRG. As Iraq’s army abandoned its positions north of Baghdad, the KRG’s Peshmerga advanced into the “disputed territories” beyond the KRG’s formal boundaries and took control of the oil-rich city of Kirkuk, the jewel in the crown of Iraqi Kurdish territorial ambitions. Thus, the Barzani-led KRG calculated it had attained the necessary political and economic conditions to contemplate outright independence. Asserting Iraq had been effectively “partitioned” and that “conditions are right,” the KRG President declared, “From now on, we will not hide that the goal of Kurdistan is independence.” 1 The viability of an independent Kurdish state will ultimately depend on the Barzani government’s ability to recalibrate its relations with its two powerful neighbors, Turkey and Iran. This, in turn, depends on the ability of Barzani’s Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) to preserve its hegemony over Iraqi Kurdistan in the face of challenges posed by its Iraqi political rival, the PUK (Patriotic Union of Kurdistan), and the Turkish-based PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party). Barzani’s objective to preserve the KDP’s authority from these threats forms one of the main drivers behind his Dr.