Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

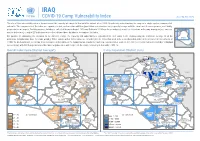

COVID-19 Camp Vulnerability Index As of 04 May 2020

IRAQ COVID-19 Camp Vulnerability Index As of 04 May 2020 The aim of this vulnerability index is to understand the capacity of camps to deal with the impact of a COVID-19 outbreak, understanding the camp as a single system composed of sub-units. The components of the index are: exposure to risk, system vulnerabilities (population and infrastructure), capacity to cope with the event and its consequences, and finally, preparedness measures. For this purpose, databases collected between August 2019 and February 2020 have been analysed, as well as interviews with camp managers (see sources next to indicators), a total of 27 indicators were selected from those databases to compose the index. For purpose of comparing the situation on the different camps, the capacity and vulnerability is calculated for each camp in the country using the arithmetic average of all the IRAQ indicators (all indicators have the same weight). Those camps with a higher value are considered to be those that need to be strengthened in order to be prepared for an outbreak of COVID-19. Each indicator, according to its relevance and relation to the humanitarian standards, has been evaluated on a scale of 0 to 100 (see list of indicators and their individual assessment), with 100 being considered the most negative value with respect to the camp's capacity to deal with COVID-19. Overall Index Score (District Average*) Camp Population (District Sum) TURKEY TURKEY Zakho Zakho Al-Amadiya 46,362 Al-Amadiya 32 26 3,205 DUHOK Sumail DUHOK Sumail Al-Shikhan 83,965 Al-Shikhan Aqra -

Iraq: Opposition to the Government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI)

Country Policy and Information Note Iraq: Opposition to the government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) Version 2.0 June 2021 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules • The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

Mandaean Human Rights Group

The Mandaean Associations Union 19 ketch road Morristown, NJ 07960, USA +973 292 0309 [email protected] www.mandaeanunion.org Mandaean Human Rights Group Mandaean Human Rights Annual Report March 2008 2 March 23, 2008 Page The Mandaean Human Rights Group is a self organized group dedicated for the help and protection of follow Mandaeans in Iraq and Iran given the situation in those two countries. The Human Rights Group watches, investigates and exposes human rights violations against Mandaeans. We have volunteers in the United States, Canada, Australia, United Kingdom, Europe and Iraq. Our model in our work is the United Nation's Human Rights Declaration of 1948. The MHRG is a non profit organization registered at Companies House, UK 6271157. It is a member of the Mandaean Associations Union . Acknowledgment We gratefully acknowledge the dedicated help and advice of many organizations, without which this work would not have been completed. Numbered among them for this edition are: 1. The Mandaean Associations Union. 2. The Spiritual Mandaean Council – Baghdad, Iraq 3. The Mandaean General Assembly – Baghdad, Iraq 4. The Mandaean Human Rights Association- Baghdad, Iraq 5. The Mandaean Society in Jordan. 6. The Mandaean Society in Syria. 7. The Mandaean Society in Australia 8. The Scientific Mandaean Society in Iran 3 March 23, 2008 Page Content: Demography ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- P 4 Short History of the Sabian Mandaeans ------------------------------------------------P 4 Sabian -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

DELIVERED on 23RD SEPTEMBER Dear President Barzani

THE LAST WRITTEN DRAFT – DELIVERED ON 23RD SEPTEMBER Dear President Barzani, I am writing on behalf of the United States to express our profound respect for you and for the people of the Iraqi Kurdistan Region. Together, over decades, we have forged a historic relationship, and it is our intention and commitment that this relationship continues to strengthen over the decades to come. Over the past three years, in particular, our strong partnership and your brave decisions to cooperate fully with the Iraqi Security Forces turned the tide against ISIS. We honor and we will never forget the sacrifice of the Peshmerga during our common struggle against terrorism. Before us at this moment is the question of a referendum on the future of the Kurdistan Region, scheduled to be held on September 25. We have expressed our concerns. These concerns include the ongoing campaign against ISIS, including upcoming operations in Hawija, the uncertain regional environment, and the need to focus intensively on stabilizing liberated areas to ensure ISIS can never return. Accordingly, we respectfully request that you accept an alternative, which we believe will better help achieve your objectives and ensure stability and peace in the wake of this necessary war against ISIS. This alternative proposal establishes a new and accelerated framework for negotiation with the central Government of Iraq led by Prime Minister Abadi. This accelerated framework for negotiation carries an open agenda and should last no longer than one year, with the possibility of renewal. Its objective is to resolve all issues outstanding between Baghdad and Erbil and the nature of the future relationship between the two. -

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq Julie Ahn—Maeve Campbell—Pete Knoetgen Client: Office of Iraq Affairs, U.S. Department of State Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Advisor: Meghan O’Sullivan Policy Analysis Exercise Seminar Leader: Matthew Bunn May 7, 2018 This Policy Analysis Exercise reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing the views of the US Government, nor those of Harvard University or any of its faculty. Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to the many people who helped us throughout the development, research, and drafting of this report. Our field work in Iraq would not have been possible without the help of Sherzad Khidhir. His willingness to connect us with in-country stakeholders significantly contributed to the breadth of our interviews. Those interviews were made possible by our fantastic translators, Lezan, Ehsan, and Younis, who ensured that we could capture critical information and the nuance of discussions. We also greatly appreciated the willingness of U.S. State Department officials, the soldiers of Operation Inherent Resolve, and our many other interview participants to provide us with their time and insights. Thanks to their assistance, we were able to gain a better grasp of this immensely complex topic. Throughout our research, we benefitted from consultations with numerous Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) faculty, as well as with individuals from the larger Harvard community. We would especially like to thank Harvard Business School Professor Kristin Fabbe and Razzaq al-Saiedi from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative who both provided critical support to our project. -

5. Kurdish Tribes

Country Policy and Information Note Iraq: Blood feuds Version 1.0 August 2017 Preface This note provides country of origin information (COI) and policy guidance to Home Office decision makers on handling particular types of protection and human rights claims. This includes whether claims are likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or discretionary leave and whether – in the event of a claim being refused – it is likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under s94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the policy guidance contained with this note; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Country Information COI in this note has been researched in accordance with principles set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI) and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, namely taking into account its relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability. All information is carefully selected from generally reliable, publicly accessible sources or is information that can be made publicly available. Full publication details of supporting documentation are provided in footnotes. Multiple sourcing is normally used to ensure that the information is accurate, balanced and corroborated, and that a comprehensive and up-to-date picture at the time of publication is provided. Information is compared and contrasted, whenever possible, to provide a range of views and opinions. -

Considerations About Semitic Etyma in De Vaan's Latin Etymological Dictionary

applyparastyle “fig//caption/p[1]” parastyle “FigCapt” Philology, vol. 4/2018/2019, pp. 35–156 © 2019 Ephraim Nissan - DOI https://doi.org/10.3726/PHIL042019.2 2019 Considerations about Semitic Etyma in de Vaan’s Latin Etymological Dictionary: Terms for Plants, 4 Domestic Animals, Tools or Vessels Ephraim Nissan 00 35 Abstract In this long study, our point of departure is particular entries in Michiel de Vaan’s Latin Etymological Dictionary (2008). We are interested in possibly Semitic etyma. Among 156 the other things, we consider controversies not just concerning individual etymologies, but also concerning approaches. We provide a detailed discussion of names for plants, but we also consider names for domestic animals. 2018/2019 Keywords Latin etymologies, Historical linguistics, Semitic loanwords in antiquity, Botany, Zoonyms, Controversies. Contents Considerations about Semitic Etyma in de Vaan’s 1. Introduction Latin Etymological Dictionary: Terms for Plants, Domestic Animals, Tools or Vessels 35 In his article “Il problema dei semitismi antichi nel latino”, Paolo Martino Ephraim Nissan 35 (1993) at the very beginning lamented the neglect of Semitic etymolo- gies for Archaic and Classical Latin; as opposed to survivals from a sub- strate and to terms of Etruscan, Italic, Greek, Celtic origin, when it comes to loanwords of certain direct Semitic origin in Latin, Martino remarked, such loanwords have been only admitted in a surprisingly exiguous num- ber of cases, when they were not met with outright rejection, as though they merely were fanciful constructs:1 In seguito alle recenti acquisizioni archeologiche ed epigrafiche che hanno documen- tato una densità finora insospettata di contatti tra Semiti (soprattutto Fenici, Aramei e 1 If one thinks what one could come across in the 1890s (see below), fanciful constructs were not a rarity. -

View/Print Page As PDF

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds In the Regional Power Struggle, has Erbil Decided to Join the Sunni Bloc? by Frzand Sherko Jan 29, 2016 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Frzand Sherko Frzand Sherko is an Iraq based strategic scholar and political analyst specializing in the intelligence and security affairs of the Kurdistan region of Iraq, greater Iraq, and the wider Islamic Middle East. Articles & Testimony he security of the Kurdistan Region-Iraq (KRI) depends more on agreements between Erbil and Kurdistan’s T neighbors than the KRI’s own security and intelligence capabilities. Whenever the regional powers surrounding the KRI have suspected that their interests are at risk, they have not hesitated to put the KRI’s security and stability in jeopardy to secure their interests. However, these regional power’s interests, increasingly at odds with one another, have begun to exacerbate the KRI’s security and internal political challenges. Since 1992, the KRI has worked to maintain a strategic relationship with Iran. When Iraqi Kurdistan’s civil war began in late 1993, Iran played a significant role, initially by directing the Islamic Movement in Kurdistan and later through its support of both sides in the conflict – the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP). Iran maintained its dual support until 1996, when it leveraged its relations to encourage both parties to maintain a political balance. Such an arrangement created stability, allowing Tehran to benefit from its economic ties with both parties and to avoid any possible threats the conflict could pose to Iranian national security. -

IRAQ: Humanitarian Operational Presence (3W) for HRP and Non-HRP Activities January to June 2021

IRAQ: Humanitarian Operational Presence (3W) for HRP and Non-HRP Activities January to June 2021 TURKEY 26 Zakho Number of partners by cluster DUHOK Al-Amadiya 11 3 Sumail Duhok 17 27 33 Rawanduz Al-Shikhan Aqra Telafar 18 ERBIL 40 Tilkaef 4 23 8 Sinjar Shaqlawa 57 4 Pshdar Al-Hamdaniya Al-Mosul 4 Rania 1 NINEWA 37 Erbil Koysinjaq 23 Dokan 1 Makhmour 2 Al-Baaj 15 Sharbazher 16 Dibis 9 24 Al-Hatra 20 Al-Shirqat KIRKUK Kirkuk Al-Sulaymaniyah 15 6 SYRIA Al-Hawiga Chamchamal 21 Halabcha 18 19 6 2 Daquq Beygee 16 12 Tooz Kalar Tikrit Khurmato 12 8 2 11 SALAH AL-DIN Kifri Al-Daur Ana 2 6 Al-Kaim 7 Samarra 15 13 Haditha Al-Khalis IRAN 3 7 Balad 12 Al-Muqdadiya Heet 9 DIYALA 7 Baquba 10 4 Baladruz Al-Kadhmiyah 5 1 Al-Ramadi 9 Al-Mada'in 1 AL-ANBAR Al-Falluja 24 28 Al-Mahmoudiya Badra 3 8 Al-Suwaira Al-Mussyab JORDAN Al-Rutba 2 1 WASSIT 2 KERBALA Al-Mahaweel 3 Al-Kut Kerbela 1 BABIL 5 2 Al-Hashimiya 3 1 2 Al-Kufa 3 Al-Diwaniya Afaq 2 MAYSAN Al-Manathera 1 1 Al-Rifai Al-Hamza AL-NAJAF Al-Rumaitha 1 1 Al-Shatra * Total number of unique partners reported under the HRP 2020, HRP 2021 and other non-HRP plans Al-Najaf 2 Al-Khidhir THI QAR 2 7 Al-Nasiriya 1 Al-Qurna Suq 1 1 2 Shat 119 Partners Al-Shoyokh 3 Al-Arab Providing humanitarian assistance from January to June Al-Basrah 3 2021 for humanitarian activities under the HRP 2021, HRP 2020 AL-BASRAH Abu SAUDI ARABIA AL-MUTHANNA 4 1 other non-HRP programmes. -

The Contemporary Roots of Kurdish Nationalism in Iraq

THE CONTEMPORARY ROOTS OF KURDISH NATIONALISM IN IRAQ Introduction Contrary to popular opinion, nationalism is a contemporary phenomenon. Until recently most people primarily identified with and owed their ultimate allegiance to their religion or empire on the macro level or tribe, city, and local region on the micro level. This was all the more so in the Middle East, where the Islamic umma or community existed (1)and the Ottoman Empire prevailed until the end of World War I.(2) Only then did Arab, Turkish, and Iranian nationalism begin to create modern nation- states.(3) In reaction to these new Middle Eastern nationalisms, Kurdish nationalism developed even more recently. The purpose of this article is to analyze this situation. Broadly speaking, there are two main schools of thought on the origins of the nation and nationalism. The primordialists or essentialists argue that the concepts have ancient roots and thus date back to some distant point in history. John Armstrong, for example, argues that nations or nationalities slowly emerged in the premodern period through such processes as symbols, communication, and myth, and thus predate nationalism. Michael M. Gunter* Although he admits that nations are created, he maintains that they existed before the rise of nationalism.(4) Anthony D. Smith KUFA REVIEW: No.2 - Issue 1 - Winter 2013 29 KUFA REVIEW: Academic Journal agrees with the primordialist school when Primordial Kurdish Nationalism he argues that the origins of the nation lie in Most Kurdish nationalists would be the ethnie, which contains such attributes as considered primordialists because they would a mythomoteur or constitutive political myth argue that the origins of their nation and of descent, a shared history and culture, a nationalism reach back into time immemorial. -

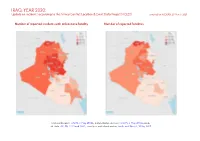

IRAQ, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

IRAQ, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018b; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018a; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 IRAQ, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Protests 1795 13 36 Conflict incidents by category 2 Explosions / Remote 1761 308 824 Development of conflict incidents from 2016 to 2020 2 violence Battles 869 502 1461 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 580 7 11 Conflict incidents per province 4 Riots 441 40 68 Violence against civilians 408 239 315 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5854 1109 2715 Disclaimer 7 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2016 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 IRAQ, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known.