Iraq's Displacement Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gurriculum Vitae

حوكمةتا هةريَما كوردستانىَ – عرياق حكومت أقليم كودستان – العراق وزارة التعليم العالي والبحث العلمي وةزراتا خوندنا باﻻ وتوذينيَت زانستى رئاست جامعت بولينكنيك دهوك سةوركاتيا زانلويا ثوليتةكنيلا دهوك Kurdistan Regional Government-Iraq Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Duhok Polytechnic University Curriculum Vitae University Address: 61 Zahko Road, 1006 Mazi Qt., Duhok , Kurdistan -Iraq A / Personal data Name: Mohammed Haydar Mosa Date of Birth: 1/1/1971 Place of Birth: Mosul City \ lraq Marital Status: Married Mother Tongue: Kurdish Other Language: Kurdish, English and Arabic Degree: M.Sc. Nursing from Nursing College/ Mosul University\ Iraq 2005 B\Educational University University Collage Degree Date (Year) Specialty Mosul Mosul Technical Technical Diploma 199 - 1993 Anesthesia Institute\Iraq Institute\Iraq Mosul College of Nursing B.SC 1994 - 1998 University Nursing Science Mosul College of Pediatric M.SC 2003 - 2005 University Nursing health nursing C\Training and education: Name ,Place , Country Type Years attended Academic degree obtained From To Tumor workshop \ Tumor 21/9/1996 - 29/9/1996 Training Mosul \Iraq nursing Second conference tumor Tumor 22/9/1996 - 24/9/1996 Training Of Mosul \Iraq Course & methods to teach public health\ Community 12 October 2004 Training Community health health nursing - 15 October 2004 nursing \ Duhok \ Iraq Cardiac catheterization Cardiac \ Azadi teaching 2007 Training catheterization hospital \Duhok\ Iraq Methods of education Methods of \Duhok Technical 4/7/2009 - 18/7/2006 education institute \Iraq Evaluation of health Environmental states At health Institutions In 7th scientific conference conference 27-28 September 2010 Iraq. Mosul proceedings university\Nursing collage The role of Scientific research in Developing 10th National scientific of public health . -

Irakin Tilannekatsaus Marraskuussa 2017

RAPORTTI MIG-1725800 06.03.00 15.12.2017 MIGDno-2017-381 IRAKIN TILANNEKATSAUS MARRASKUUSSA 2017 Sisällys 1. Yleinen tilanne syksyllä 2017.....................................................................................................1 2. Turvallisuustilanne...................................................................................................................19 2.1. Väkivallan ilmenemismuodot ja voimakkuus .....................................................................19 2.2. Konfliktin luonne ja osapuolet............................................................................................20 2.2.1. Valtiolliset turvallisuusjoukot .......................................................................................20 2.2.2. Valtiota vastustavat ja muut aseelliset ryhmät ............................................................21 2.3. Siviilikuolemat ja loukkaantuneet.......................................................................................21 3. Turvallisuustilanne alueittain....................................................................................................22 4. Maan sisäisesti siirtymään joutuneet ja pakolaiset...................................................................44 5. Humanitaarinen tilanne............................................................................................................44 UNDP 28.6.2017. Rebuilding lives and neighbourhoods after conflict. Osoitteessa (30.11.2017): http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/blog/2017/6/28/Housing- by-people-rebuilding-lives-and-neighbourhoods-after-conflict.html...........................................64 -

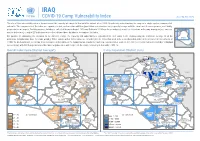

COVID-19 Camp Vulnerability Index As of 04 May 2020

IRAQ COVID-19 Camp Vulnerability Index As of 04 May 2020 The aim of this vulnerability index is to understand the capacity of camps to deal with the impact of a COVID-19 outbreak, understanding the camp as a single system composed of sub-units. The components of the index are: exposure to risk, system vulnerabilities (population and infrastructure), capacity to cope with the event and its consequences, and finally, preparedness measures. For this purpose, databases collected between August 2019 and February 2020 have been analysed, as well as interviews with camp managers (see sources next to indicators), a total of 27 indicators were selected from those databases to compose the index. For purpose of comparing the situation on the different camps, the capacity and vulnerability is calculated for each camp in the country using the arithmetic average of all the IRAQ indicators (all indicators have the same weight). Those camps with a higher value are considered to be those that need to be strengthened in order to be prepared for an outbreak of COVID-19. Each indicator, according to its relevance and relation to the humanitarian standards, has been evaluated on a scale of 0 to 100 (see list of indicators and their individual assessment), with 100 being considered the most negative value with respect to the camp's capacity to deal with COVID-19. Overall Index Score (District Average*) Camp Population (District Sum) TURKEY TURKEY Zakho Zakho Al-Amadiya 46,362 Al-Amadiya 32 26 3,205 DUHOK Sumail DUHOK Sumail Al-Shikhan 83,965 Al-Shikhan Aqra -

Iraq: Opposition to the Government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI)

Country Policy and Information Note Iraq: Opposition to the government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) Version 2.0 June 2021 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules • The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq

HUMAN RIGHTS UNAMI Office of the United Nations United Nations Assistance Mission High Commissioner for for Iraq – Human Rights Office Human Rights Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq: 11 December 2014 – 30 April 2015 “The United Nations has serious concerns about the thousands of civilians, including women and children, who remain captive by ISIL or remain in areas under the control of ISIL or where armed conflict is taking place. I am particularly concerned about the toll that acts of terrorism continue to take on ordinary Iraqi people. Iraq, and the international community must do more to ensure that the victims of these violations are given appropriate care and protection - and that any individual who has perpetrated crimes or violations is held accountable according to law.” − Mr. Ján Kubiš Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General in Iraq, 12 June 2015, Baghdad “Civilians continue to be the primary victims of the ongoing armed conflict in Iraq - and are being subjected to human rights violations and abuses on a daily basis, particularly at the hands of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Ensuring accountability for these crimes and violations will be paramount if the Government is to ensure justice for the victims and is to restore trust between communities. It is also important to send a clear message that crimes such as these will not go unpunished’’ - Mr. Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 12 June 2015, Geneva Contents Summary ...................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

Research Notes

RESEARCH NOTES The Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ No. 38 ■ Oc t ober 2016 How to Secure Mosul Lessons from 2008—2014 MICHAEL KNIGHTS N EARLY 2017, Iraqi security forces (ISF) are likely to liberate Mosul from Islamic State control. But given the dramatic comebacks staged by the Islamic State and its predecessors in the city in I2004, 2007, and 2014, one can justifiably ask what will stop IS or a similar movement from lying low, regenerating, and wiping away the costly gains of the current war. This paper aims to fill an important gap in the literature on Mosul, the capital of Ninawa province, by looking closely at the underexplored issue of security arrangements for the city after its liberation, in particular how security forces should be structured and controlled to prevent an IS recurrence. Though “big picture” politi- cal deals over Mosul’s future may ultimately be decisive, the first priority of the Iraqi-international coalition is to secure Mosul. As John Paul Vann, a U.S. military advisor in Vietnam, noted decades ago: “Security may be ten percent of the problem, or it may be ninety percent, but whichever it is, it’s the first ten percent or the first ninety percent. Without security, nothing else we do will last.”1 This study focuses on two distinct periods of Mosul’s Explanations for both the 2007–2011 successes and recent history. In 2007–2011, the U.S.-backed Iraqi the failures of 2011–2014 are easily identified. In the security forces achieved significant success, reducing earlier span, Baghdad committed to Mosul’s stabilization security incidents in the city from a high point of 666 and Iraq’s prime minister focused on the issue, authoriz- per month in the first quarter of 2008 to an average ing compromises such as partial amnesty and a reopen- of 32 incidents in the first quarter of 2011. -

Uniting for the Shared Battle Short-Term Ceasefires in Middle East Conflicts to Prevent Humanitarian Disaster

UNITING FOR THE SHARED BATTLE SHORT-TERM CEASEFIRES IN MIDDLE EAST CONFLICTS TO PREVENT HUMANITARIAN DISASTER October 2020 Mahnaz Lashkri - Brian Reeves SUMMARY The COVID-19 pandemic has reminded the world of the need to prevent a sudden unforeseen health crisis from leading to total ruin. A pandemic or similar major health crisis cannot alone be counted on to align the interests of the Middle East’s complex conflicts between states, non-state actors, and regional and extra-regional powers on the need for a ceasefire, but it could provide the context for a ripe moment to broker one. Short-term ceasefires, if built substantively and with critical buy-in from the most powerful actors, are achievable to facilitate humanitarian work to prevent or mitigate outbreaks amongst highly vulnerable populations in conflict zones. PROBLEM: CONFLICTS BLOCKING HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE IN THE WAKE OF A MAJOR HEALTH CRISIS The Middle East has sustained tremendous tumult in the past decade, leaving many countries already with sys- temic governance deficiencies even more vulnerable to instability. Being economically strained beyond their limits and racked by conflict, they are also unable to properly cope with refugee inflows. The threat COVID-19 poses for the conflict-ridden region has proven just how quickly a disaster can catch leaders off guard and potentially turn dire situations into uncontrollable catastrophes. New unforeseen major health crises for the region are inevitable, whether they be another pandemic or drought-induced famine, a particular danger as global temperatures rise. Standing in the way of a crisis response effort are the region’s ongoing conflicts and the competing interests of their belligerent parties and stakeholders, which often torpedo ceasefire attempts, no matter the humanitarian toll. -

The Syrian Civil War a New Stage, but Is It the Final One?

THE SYRIAN CIVIL WAR A NEW STAGE, BUT IS IT THE FINAL ONE? ROBERT S. FORD APRIL 2019 POLICY PAPER 2019-8 CONTENTS * SUMMARY * 1 INTRODUCTION * 3 BEGINNING OF THE CONFLICT, 2011-14 * 4 DYNAMICS OF THE WAR, 2015-18 * 11 FAILED NEGOTIATIONS * 14 BRINGING THE CONFLICT TO A CLOSE * 18 CONCLUSION © The Middle East Institute The Middle East Institute 1319 18th Street NW Washington, D.C. 20036 SUMMARY Eight years on, the Syrian civil war is finally winding down. The government of Bashar al-Assad has largely won, but the cost has been steep. The economy is shattered, there are more than 5 million Syrian refugees abroad, and the government lacks the resources to rebuild. Any chance that the Syrian opposition could compel the regime to negotiate a national unity government that limited or ended Assad’s role collapsed with the entry of the Russian military in mid- 2015 and the Obama administration’s decision not to counter-escalate. The country remains divided into three zones, each in the hands of a different group and supported by foreign forces. The first, under government control with backing from Iran and Russia, encompasses much of the country, and all of its major cities. The second, in the east, is in the hands of a Kurdish-Arab force backed by the U.S. The third, in the northwest, is under Turkish control, with a mix of opposition forces dominated by Islamic extremists. The Syrian government will not accept partition and is ultimately likely to reassert its control in the eastern and northwestern zones. -

Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region

KURDISTAN RISING? CONSIDERATIONS FOR KURDS, THEIR NEIGHBORS, AND THE REGION Michael Rubin AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region Michael Rubin June 2016 American Enterprise Institute © 2016 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any man- ner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. The views expressed in the publications of the American Enterprise Institute are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. American Enterprise Institute 1150 17th St. NW Washington, DC 20036 www.aei.org. Cover image: Grand Millennium Sualimani Hotel in Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan, by Diyar Muhammed, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons. Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Who Are the Kurds? 5 2. Is This Kurdistan’s Moment? 19 3. What Do the Kurds Want? 27 4. What Form of Government Will Kurdistan Embrace? 56 5. Would Kurdistan Have a Viable Economy? 64 6. Would Kurdistan Be a State of Law? 91 7. What Services Would Kurdistan Provide Its Citizens? 101 8. Could Kurdistan Defend Itself Militarily and Diplomatically? 107 9. Does the United States Have a Coherent Kurdistan Policy? 119 Notes 125 Acknowledgments 137 About the Author 139 iii Executive Summary wo decades ago, most US officials would have been hard-pressed Tto place Kurdistan on a map, let alone consider Kurds as allies. Today, Kurds have largely won over Washington. -

BACKGROUND GUIDE UNSC BBPS – Glengaze – MUN

BACKGROUND GUIDE UNSC BBPS – Glengaze – MUN Agenda – “Peace Building Measures in Post Conflict Regions with Special Emphasis on Iraq and Libya.” LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE BOARD Greetings, We welcome you to the United Nations Security Council, in the capacity of the members of the Executive Board of the said conference. Since this conference shall be a learning experience for all of you, it shall be for us as well. Our only objective shall be to make you all speak and participate in the discussion, and we pledge to give every effort for the same. How to research for the agenda and beyond? There are several things to consider. This background guide shall be different from the background guides you might have come across in other MUNs and will emphasise more on providing you the right Direction where you find matter for your research than to provide you matter itself, because we do not believe in spoon- feeding you, nor do we believe in leaving you to swim in the pond all by yourself. However, we promise that if you read the entire set of documents so provided, you shall be able to cover 70% of your research for the conference. The remaining amount of research depends on how much willing are you to put in your efforts and understand those articles and/or documents. So, in the purest of the language we can say, it is important to read anything and everything whose links are provided in the background guide. What to speak in the committee and in what manner? The basic emphasis of the committee shall not be on how much facts you read and present in the committee but how you explain them in simple and decent language to us and the fellow committee members. -

The Challenges and Opportunities of Agricultural Development in Iraqi Kurdistan

land Article From Producers to Consumers: The Challenges and Opportunities of Agricultural Development in Iraqi Kurdistan Lina Eklund 1,*, Abdulhakim Abdi 2 and Mine Islar 3 1 Center for Middle Eastern Studies (CMES), Lund University, 223 62 Lund, Sweden 2 Department of Physical Geography and Ecosystem Science, Lund University, 223 62 Lund, Sweden; [email protected] 3 Lund University Centre for Sustainability Studies (LUCSUS), Lund University, 223 62 Lund, Sweden; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +46-46-222-9609 Academic Editors: Fabian Löw, Alexander Prishchepov and Florian Schierhorn Received: 28 April 2017; Accepted: 20 June 2017; Published: 22 June 2017 Abstract: Agriculture and rural life in the Middle East have gone through several changes in the past few decades. The region is characterized by high population growth, urbanization, and water scarcity, which poses a challenge to maintaining food security and production. This paper investigates agricultural and rural challenges in the Duhok governorate of Iraqi Kurdistan from biophysical, political, and socio-economic perspectives. Satellite data is used to study land use and productivity, while a review of government policies and interview data show the perspectives of the government and the local population. Our results reveal that these perspectives are not necessarily in line with each other, nor do they correspond well with the biophysical possibilities. While the government has been trying to increase agricultural productivity, satellite data show that yields have been declining since 2000. Furthermore, a lack of services in rural areas is driving people to cities to seek better opportunities, which means that the local population’s incentive to increase agricultural activity is low. -

The Extent and Geographic Distribution of Chronic Poverty in Iraq's Center

The extent and geographic distribution of chronic poverty in Iraq’s Center/South Region By : Tarek El-Guindi Hazem Al Mahdy John McHarris United Nations World Food Programme May 2003 Table of Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................1 Background:.........................................................................................................................................3 What was being evaluated? .............................................................................................................3 Who were the key informants?........................................................................................................3 How were the interviews conducted?..............................................................................................3 Main Findings......................................................................................................................................4 The extent of chronic poverty..........................................................................................................4 The regional and geographic distribution of chronic poverty .........................................................5 How might baseline chronic poverty data support current Assessment and planning activities?...8 Baseline chronic poverty data and targeting assistance during the post-war period .......................9 Strengths and weaknesses of the analysis, and possible next steps:..............................................11