Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Speaker Materials

Speaker Materials Partnering organizations: The Akdamut – an Aramaic preface to our Torah Reading Rabbi Gesa S. Ederberg ([email protected]) ַאְקָדּמוּת ִמִלּין ְוָשָׁריוּת שׁוָּת א Before reciting the Ten Commandments, ַאְוָלא ָשֵׁקְלָא ַהְרָמןְוּרשׁוָּת א I first ask permission and approval ְבָּבֵבי ְתֵּרי וְּתַלת ְדֶאְפַתְּח בּ ַ ְקשׁוָּת א To start with two or three stanzas in fear ְבָּבֵרְי דָבֵרי ְוָטֵרי ֲעֵדי ְלַקִשּׁישׁוָּת א Of God who creates and ever sustains. ְגּבָוּרן ָעְלִמין ֵלהּ ְוָלא ְסֵפק ְפִּרישׁוָּת א He has endless might, not to be described ְגִּויל ִאְלּוּ רִקיֵעי ְק ֵ ָי כּל חְוּרָשָׁת א Were the skies parchment, were all the reeds quills, ְדּיוֹ ִאלּוּ ַיֵמּי ְוָכל ֵמיְכִישׁוָּת א Were the seas and all waters made of ink, ָדְּיֵרי ַאְרָעא ָסְפֵרי ְוָרְשֵׁמַי רְשָׁוָת א Were all the world’s inhabitants made scribes. Akdamut – R. Gesa Ederberg Tikkun Shavuot Page 1 of 7 From Shabbat Shacharit: ִאלּוּ פִ יוּ מָ לֵא ִשׁיָרה ַכָּיּ ם. וּלְשׁו ֵוּ ִרָנּה כַּהֲמון גַּלָּיו. ְושְפתוֵתיוּ ֶשַׁבח ְכֶּמְרֲחֵבי ָ רִקיַע . וְעֵיֵיוּ ְמִאירות ַכֶּשֶּׁמ שׁ ְוַכָיֵּרַח . וְ יָדֵ יוּ פְ רוּשות כְּ ִ ְשֵׁרי ָשָׁמִי ם. ְוַרְגֵליוּ ַקלּות ָכַּאָיּלות. ֵאין אֲ ַ ְחוּ ַמְסִפּיִקי ם לְהודות לְ ה' אֱ להֵ יוּ וֵאלהֵ י ֲאבוֵתיוּ. וְּלָבֵר ֶאת ְשֶׁמ עַל ַאַחת ֵמֶאֶלף ַאְלֵפי אֲלָ ִפי ם ְוִרֵבּי ְרָבבות ְפָּעִמי ם Were our mouths filled with song as the sea, our tongues to sing endlessly like countless waves, our lips to offer limitless praise like the sky…. We would still be unable to fully express our gratitude to You, ADONAI our God and God of our ancestors... Akdamut – R. Gesa Ederberg Tikkun Shavuot Page 2 of 7 Creation of the World ֲהַדר ָמֵרי ְשַׁמָיּא ְו ַ שׁ ִלְּיט בַּיֶבְּשָׁתּ א The glorious Lord of heaven and earth, ֲהֵקים ָעְלָמא ְיִחָידאי ְוַכְבֵּשְׁהּ בַּכְבּשׁוָּת א Alone, formed the world, veiled in mystery. -

The Babylonian Talmud

The Babylonian Talmud translated by MICHAEL L. RODKINSON Book 10 (Vols. I and II) [1918] The History of the Talmud Volume I. Volume II. Volume I: History of the Talmud Title Page Preface Contents of Volume I. Introduction Chapter I: Origin of the Talmud Chapter II: Development of the Talmud in the First Century Chapter III: Persecution of the Talmud from the destruction of the Temple to the Third Century Chapter IV: Development of the Talmud in the Third Century Chapter V: The Two Talmuds Chapter IV: The Sixth Century: Persian and Byzantine Persecution of the Talmud Chapter VII: The Eight Century: the Persecution of the Talmud by the Karaites Chapter VIII: Islam and Its Influence on the Talmud Chapter IX: The Period of Greatest Diffusion of Talmudic Study Chapter X: The Spanish Writers on the Talmud Chapter XI: Talmudic Scholars of Germany and Northern France Chapter XII: The Doctors of France; Authors of the Tosphoth Chapter XIII: Religious Disputes of All Periods Chapter XIV: The Talmud in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries Chapter XV. Polemics with Muslims and Frankists Chapter XVI: Persecution during the Seventeenth Century Chapter XVII: Attacks on the Talmud in the Nineteenth Century Chapter XVIII. The Affair of Rohling-Bloch Chapter XIX: Exilarchs, Talmud at the Stake and Its Development at the Present Time Appendix A. Appendix B Volume II: Historical and Literary Introduction to the New Edition of the Talmud Contents of Volume II Part I: Chapter I: The Combination of the Gemara, The Sophrim and the Eshcalath Chapter II: The Generations of the Tanaim Chapter III: The Amoraim or Expounders of the Mishna Chapter IV: The Classification of Halakha and Hagada in the Contents of the Gemara. -

What Is the Aggadah Problem?

Chapter 1 Ļ ļ What Is the Aggadah Problem? he term aggadah is so widely used in the Talmud and early related literature that one would think it easy to ascertain its meaning. But the Talmudic masters do not provide us with formal definitions of their procedural terms. As it T were, they seem too busy with their Torah work to step away from it and initiate outsiders into the nature of their analytic tools. Their terminological pragmatics was emulated by those who transmitted their teachings and the redactors who reduced these oral records to the written texts we still study. Since the rabbinic study tradition has never died out, this practice is, to a considerable extent, satisfactory. But particularly for those interested in how the rabbis thought about their belief—their “philosophizing” in a quite loose sense of the word—this absence of definition is disturbing and barely re- lieved by the common expedient of defining aggadah in terms of what it is not, namely, that it is Jewish law’s nonlegal accompaniment. A philological approach to a positive understanding does not help us much. Though the Hebrew root of the term, n-g-d, is well attested in the Bible and carries the primary meaning of “tell,” the noun form with its collective sense appears only in rabbinic literature. Wilhelm Bacher’s pioneering efforts to trace a path from the biblical “telling” to the polysemy of the rabbinic usage has not convinced most later schol- ars and their several alternative proposals have themselves not re- solved the issue.1 Turning to the Talmud, we quickly encounter a reason for some of this terminological indeterminacy when we look at the use of the Hebrew version of this term, haggadah. -

Yeshivat Har Etzion Israel Koschitzky Virtual Beit Midrash (Vbm) ********************************************************* Yhe-Holiday: Special Shavuot 5776 Shiur

YESHIVAT HAR ETZION ISRAEL KOSCHITZKY VIRTUAL BEIT MIDRASH (VBM) ********************************************************* YHE-HOLIDAY: SPECIAL SHAVUOT 5776 SHIUR To Whom Did God Speak at Sinai? By Harav Yaakov Medan Translated by David Strauss The Torah is ambiguous about the question of whether the Revelation at Mount Sinai was only to Moshe – "Lo, I come to you in a thick cloud, that the people may hear when I speak with you and believe you forever" (Shemot 19:9) – or to the entire people – "For on the third day the Lord will come down in the sight of all the people upon Mount Sinai" (Shemot 19:11). Another question arises as well: Did the glory of God reach the foot of the mountain, down to the Israelite camp – "And Mount Sinai smoked in every part, because the Lord descended upon it in fire, and the smoke of it ascended like the smoke of a furnace, and the whole mountain quaked greatly" (Shemot 19:18) – or did God's glory rest only on the top of the mountain – "And the Lord came down upon Mount Sinai, on the top of the mountain, and the Lord called Moshe up to the top of the mount; and Moshe went up" (Shemot 19:20)? Furthermore, if all the people stood at the foot of the mountain, to where did the priests ascend after the sweeping warning not to go up the mountain or even touch its perimeter? Let us first consider three generally accepted interpretations of the Revelation. The words of the Rambam suggest that God did not speak directly to the people of Israel. -

Appendix: a Guide to the Main Rabbinic Sources

Appendix: A Guide to the Main Rabbinic Sources Although, in an historical sense, the Hebrew scriptures are the foundation of Judaism, we have to turn elsewhere for the documents that have defined Judaism as a living religion in the two millennia since Bible times. One of the main creative periods of post-biblical Judaism was that of the rabbis, or sages (hakhamim), of the six centuries preceding the closure of the Babylonian Talmud in about 600 CE. These rabbis (tannaim in the period of the Mishnah, followed by amoraim and then seboraim), laid the foundations of subsequent mainstream ('rabbinic') Judaism, and later in the first millennium that followers became known as 'rabbanites', to distinguish them from the Karaites, who rejected their tradition of inter pretation in favour of a more 'literal' reading of the Bible. In the notes that follow I offer the English reader some guidance to the extensive literature of the rabbis, noting also some of the modern critical editions of the Hebrew (and Aramaic) texts. Following that, I indicate the main sources (few available in English) in which rabbinic thought was and is being developed. This should at least enable readers to get their bearings in relation to the rabbinic literature discussed and cited in this book. Talmud For general introductions to this literature see Gedaliah Allon, The Jews in their Land in the Talmudic Age, 2 vols (Jerusalem, 1980-4), and E. E. Urbach, The Sages, tr. I. Abrahams (Cambridge, Mass., and London: Harvard University Press, 1987), as well as the Reference Guide to Adin Steinsaltz's edition of the Babylonian Talmud (see below, under 'English Transla tions'). -

Name and Etymology in the Midrash Genesis Rabbah Name Und Etymologie Im Midrasch Genesis Rabba

Name and Etymology in the Midrash Genesis Rabbah Name und Etymologie im Midrasch Genesis Rabba MASTERARBEIT zur Erlangung des Mastergrades an der Kultur- und Gesellschaftswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Salzburg Zentrum für jüdische Kulturgeschichte Betreuerin: Univ.-Prof.in Dr.in Susanne Plietzsch eingereicht von CHRISTINA KATSIKADELI (9424798) Salzburg, am 1.6.2019 Abstract The present thesis is conceived of as a contribution to analysing early Rabbinic thought and heuristics in the context of the history of onomastics, the study of names. In particular, it focuses on the “etymology” of (mainly) biblical personal names and toponyms and the treatment of double names, as presented in the Midrash Genesis Rabbah. It is a commonplace that the early Rabbinic texts offer no support for the idea that the determination of lexical meaning also serves to clarify the historical relationship of the biblical word- forms, i.e. the early rabbis were not interested in etymological surveys from a modern point of view, cf. Samely (2002: 376). Nevertheless, the meaning interpretation of a biblical proper name according to the semantic value of its components in a narrative context is one of the most frequently employed metalinguistic structures found within the Hebrew Bible, and plays a prominent role in rabbinic literature as well. In the latter, not only the biblical name interpretation finds a direct continuation in the semantic analysis of names of biblical figures, but also names of earlier sages of the rabbinic tradition are analysed semantically. The thesis intends to sketch out a) a typology of the “etymologizing” devices and their form, i.e. which groups of names of personal names and toponyms are concerned and on which level these etymologies do occur: phonological, morphological, semantical, syntactical, and b) their function within the midrash as narratological elements: This point includes further linguistic devices such as the analysis of the biblical text in its wider semiotic constitution (as opposed to narrowly linguistic, based i.a. -

The Ways of the Sages and the Way of the World

Texte und Studien zum Antiken Judentum herausgegeben von Martin Hengel und Peter Schäfer 26 The Ways of the Sages and the Way of the World The Minor Tractates of the Babylonian Talmud: Derekh 'Eretz Rabbah Derekh 'Eretz Zuta Pereq ha-Shalom Translated on the basis of the manuscripts and provided with a commentary by Marcus van Loopik J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck) Tubingen CIP- Titelaufnahme der Deutschen Bibliothek Loopik, Marcus van: The ways of the sages and the way of the world : the minor tractates of the Babylonian Talmud: Derekh 'Eretz Rabbah, Derekh 'Eretz Zuta, Pereq ha-Shalom / transl. on the basis of the ms. and provided with a commentary by Marcus van Loopik. -Tiibingen : Möhr, 1991 (Texte und Studien zum antiken Judentum ; 26) ISBN 3-16-145644-0 ISSN 0721-8753 NE: GT © 1991 by J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), P.O. Box 2040, D-7400 Tübingen. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to repro- ductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset and printed by Guide-Druck in Tübingen on acid free stock paper from Papierfabrik Buhl in Ettlingen and bound by Heinrich Koch in Tübingen. Printed in Germany. Preface The texts in this book contain the translation and commentary of the Derekh 'Eretz tractates. The book may contribute to a better understanding of early rabbinical literature. The interpretation of these tractates leads us to a deeper insight into the relation between law and morality and between the law and the spirit of the law. -

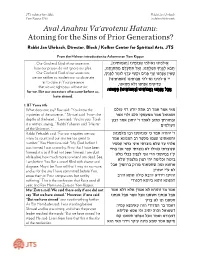

Aval Anahnu Va'avotenu Hatanu: Atoning for the Sins of Prior Generations?

JTS webinar for rabbis Rabbi Jan Uhrbach Yom Kippur 5780 [email protected] Aval Anahnu Va'avotenu Hatanu: Atoning for the Sins of Prior Generations? Rabbi Jan Uhrbach, Director, Block / Kolker Center for Spiritual Arts, JTS From the Mahzor: introduction to Ashamnu on Yom Kippur אֱ -�הֵֽ ינוּ וֵ א-�הֵ י אֲ בוֹתֵֽ ינוּ [וְאִ מּוֹתֵ ינוּ], ,Our God and God of our ancestors תָּ בֹא לְפָ נֶי� תְּ פִ לָּתֵ נוּ, וְ אַל תִּתְ עַ לַּם מִתְּחִ נָּתֵ נוּ, .hear our prayer; do not ignore our plea שֶׁאֵ ין אֲ נַֽחְ נוּ עַ זֵּי פָנִים וּקְ שֵׁ י עֹרֶ ף לוֹמַ ר לְפָ נֶי�, ,Our God and God of our ancestors יי אֱ -�הֵ ינוּ וֵא-�הֵ י אֲ בוֹתֵ ינוּ [וְאִ מּוֹתֵ ינוּ] we are neither so insolent nor so obstinate as to claim in Your presence צַ דִּ יקִ י ם אֲ נַ חְ נ וּ וְ � א חָ טָ א נ וּ , that we are righteous, without sin; אֲבָ ל אֲ נַחְ נוּ וַאֲבוֹתֵ ינוּ [וְאִ מּוֹתֵ ינוּ] חָטָ אנוּ: for we, like our ancestors who came before us, have sinned. 1. BT Yoma 87b מאי אמר אמר רב אתה יודע רזי עולם What does one say? Rav said: "You know the ושמואל אמר ממעמקי הלב ולוי אמר mysteries of the universe...” Shmuel said: “From the ובתורתך כתוב לאמר ר' יוחנן אמר רבון depths of the heart...” Levi said: “And in your Torah העולמים it is written, saying...” Rabbi Yohanan said: “Master of the Universe...” ר' יהודה אמר כי עונותינו רבו מלמנות Rabbi Yehudah said: “For our iniquities are too וחטאתינו עצמו מספר רב המנונא אמר many to count and our sins are too great to אלהי עד שלא נוצרתי איני כדאי עכשיו number.” Rav Hamnuna said: "My God, before I שנוצרתי כאילו לא נוצרתי עפר אני בחיי was formed I was unworthy. -

Equity in American and Jewish Law

Touro Law Review Volume 36 Number 1 Article 11 2020 Equity in American and Jewish Law Itzchak E. Kornfeld , Ph.D. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview Part of the Common Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Contracts Commons, Courts Commons, International Law Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Legal Commons Recommended Citation Kornfeld, Itzchak E. , Ph.D. (2020) "Equity in American and Jewish Law," Touro Law Review: Vol. 36 : No. 1 , Article 11. Available at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol36/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Touro Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kornfeld: Equity in American and Jewish Law EQUITY IN AMERICAN AND JEWISH LAW Itzchak E. Kornfeld, Ph.D.* I. INTRODUCTION This article examines the subject of equity in the laws of the United States and in Jewish law.1 The equitable principles and remedies in the law of the United States are rooted in the common law of England. Their origins are more fully elaborated upon below. The equitable principles in Jewish law, as established in the Talmud, specifically in the Mishna and Gemara, are rooted in the Torah,2 which * Ph.D. (Law), The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. General Counsel and V.P. M.E. J. Transboundary Development, Ltd., Israel. This article is dedicated to Rabbi Aaron HaCohen Gold and to Bella and Ben Schepsman, as well as to the memories of Rabbi Aaron Kirschenbaum and R. -

The Encyclopedia of Talmudic Sages

THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF TALMUDIC SAGES Gershom Bader translated by Solomon Katz Jason Aronson Inc. Northvale, N:J. London Contents Foreword ix Part I Mishnah 1 Introduction 3 2 The Three Main Parties of the Talmudic Period 21 3 The Samaritans 34 4 Simon the Just 42 5 Antigonos of Socho 49 6 Jose ben Joezer and Jose ben Jochanan 53 7 Jochanan the High Priest 59 8 Joshua ben Perachiah and Nittai of Arbela 68 9 Jehudah ben Tabbai and Simeon ben Shetach 72 0 Shemaiah and Abtalion 79 1 The Men of Bathyra 85 vi Contents 12 Choni the Circle Drawer 89 13 Hillel 94 14 Shammai—Hillel's Colleague 107 15 Akabia ben Mahalalel 116 16 Rabban Gamaliel the Elder 121 17 Rabban Simeon ben Gamaliel 127 18 Rabbi Chanina, Deputy to the High Priest, and His Contemporaries 133 19 The Time of the Destruction of the Temple 138 20 Rabban Jochanan ben Zakkai 152 21 The Colleagues of Rabban Jochanan ben Zakkai 164 22 Rabbi Chanina ben Dosa 175 23 Rabban Gamaliel II of Jabneh 182 24 Rabbi Eliezer ben Hyrcanus 193 25 Rabbi Joshua ben Chananiah 205 26 Rabbi Eliezer of Modiin 217 27 Onkelos (Aquilas) the Proselyte 222 28 Rabbi Eleazar ben Azariah 228 29 Rabbi Ishmael ben Elisha 236 30 Rabbi Tarphon 246 31 Rabbi Jose of Galilee 251 32 Rabbi Akiba ben Joseph 257 33 The Ten Martyrs 280 34 Simeon ben Azai and Simeon ben Zoma 295 35 Elisha ben Avuyah-"Acher" 303 36 Rabban Simeon ben Gamaliel II 311 37 Rabbi Nathan of Babylonia 320 38 Rabbi Meir 328 39 Rabbi Jehudah bar Elai 341 40 Rabbi Jose ben Chalafta 347 41 Rabbi Simeon ben Yochai 352 42 Rabbi Eleazar ben Shamua and Rabbi -

Between Rome and Babylon

Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism Texte und Studien zum Antiken Judentum Edited by Martin Hengel and Peter Schäfer 108 Aharon Oppenheimer Between Rome and Babylon Studies in Jewish Leadership and Society Edited by Nili Oppenheimer Mohr Siebeck Aharon Oppenheimer, bora 1940, is Sir Isaac Wolfson Professor of Jewish Studies at Tel Aviv University. He is the author of Babylonia Judaica in the Talmudic Period. ISBN 3-16-148514-9 ISSN 0721-8753 (Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism) Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de. © 2005 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproduc- tions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Martin Fischer in Tübingen, printed by Guide-Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. To Yael and Zahi Hilat and Yoni Acknowledgements Professors Martin Hengel and Peter Schäfer invited me to include this collection of my papers in the series they edit; I am grateful to them for their initiative. I would also like to thank the publishers, Mohr Siebeck, and in particular Dr Henning Ziebritzki, for making this proposal a reality. The work of translating the papers which appeared in Hebrew was carried out by two experienced, faithful and dedicated translators - Dr Susan Weingarten from the Department of Jewish History at Tel Aviv University translated the English and Dr Dafna Mach from the Department of German Language and Literature at the Hebrew University translated the German. -

The Jewish-Christian Controversy. Volume I History

Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism Texte und Studien zum Antiken Judentum Edited by Peter Schäfer (Princeton, NJ) Annette Y. Reed (Philadelphia, PA) Seth Schwartz (New York, NY) Azzan Yadin (New Brunswick, NJ) 56 Samuel Krauss The Jewish-Christian Controversy from the earliest times to 1789 Volume I History Edited and revised by William Horbury Mohr Siebeck ISBN 978-3-16-149643-1 ISSN 0721-8753 (Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliogra- phie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. Unrevised Paperback Edition 2008. © 1995 Samuel Krauss and William Horbury. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permit- ted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic- systems. The book was typeset by Guide-Druck in Tübingen using Sabon typcface, printed on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Held in Rottenburg. Printed in Germany. Contents Foreword VII Editorial Note XI Chapter I The Ancient World i. The Subject-matter of Polemic 1 1. Pre-Christian Background 1 2. Christian Origins 3 3. Rabbinic Apologetic 5 4. Anti-Jewish Argument 13 ii. The Early Christian Controversialists 26 iii. Public Religious Discussions 43 Chapter II Mediaeval and Later Controversy i. History of the Controversy 53 1. The background of mediaeval debate 53 2. Early mediaeval Gaul, Italy and Spain 56 3. Byzantium and Russia 61 4. France and England 68 5.