Appendix: a Guide to the Main Rabbinic Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Should Bakeries Which Are Open on Shabbat Be Supervised? a Response to the Rabinowitz-Weisberg Opinion RABBI HOWARD HANDLER

Should Bakeries Which are Open on Shabbat Be Supervised? A Response to the Rabinowitz-Weisberg Opinion RABBI HOWARD HANDLER This paper was submitted as a response to the responsum written by Rabbi Mayer Rabinowitz and Ms. Dvora Weisberg entitled "Rabbinic Supervision of Jewish Owned Businesses Operating on Shabbat" which was adopted by the CJLS on February 26, 1986. Should rabbis offer rabbinic supervision to bakeries which are open on Shabbat? i1 ~, '(l) l'\ (1) The food itself is indeed kosher after Shabbat, once the time required to prepare it has elapsed. 1 The halakhah is according to Rabbi Yehudah and not according to the Mishnah which is Rabbi Meir's opinion. (2) While a Jew who does not observe all the mitzvot is in some instances deemed trustworthy, this is never the case regarding someone who flagrantly disregards the laws of Shabbat, especially for personal profit. Maimonides specifically excludes such a person's trustworthiness regarding his own actions.2 Moreover in the case of n:nv 77n~ (a violator of Shabbat) Maimonides explicitly rejects his trustworthiness. 3 No support can be brought from Moshe Feinstein who concludes, "even if the proprietor closes his store on Shabbat, [since it is known to all that he does not observe Shabbat], we assume he only wants to impress other observant Jews so they will buy from him."4 Previously in the same responsum R. Feinstein emphasizes that even if the person in The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halakhah for the Conservative movement. -

ACC14 and Tctacci2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures B.Pdf

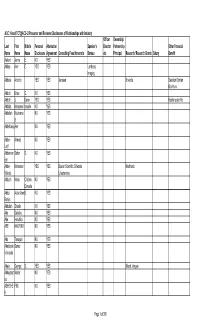

ACC.14 and TCT@ACC-i2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures of Relationships with Industry Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Aaland Jenna E. NO YES Abbas Amr E. YES YES Lantheus Imaging Abbate Antonio YES YES Janssen Novartis Swedish Orphan Biovitrum Abbott Brian G. NO YES Abbott J. Dawn YES YES Boston scientific Abdalla Mohamed Ismaile NO YES Abdallah Mouhama NO YES d Abdelbaky Amr NO YES Abdel- Ahmed NO YES Latif Abdelmon Sahar S. NO YES eim Abdel- Mohamed YES YES Boston Scientific, Edwards Medtronic Wahab Lifesciences Abduch Maria Cristina NO YES Donadio Abdul Aizai Azan B. NO YES Rahim Abdullah Shuaib NO YES Abe Daisuke NO YES Abe Haruhiko NO YES ABE NAOYUKI NO YES Abe Takayuki NO YES Abedzade Sanaz NO YES h Anaraki Abela George S. YES YES Merck, Amgen Abhayarat Walter NO YES na ABHISHE FNU NO YES K Page 1 of 350 Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Abidi Syed NO YES Abidov Aiden NO YES Abi-samra Freddy Michel NO YES Abizaid Alexandre YES YES Abbott, Boston Scientific Abo- Elsayed NO YES Salem Abou- Alex NO YES Chebl AbouEzze Omar F NO YES ddine Aboulhosn Jamil A. YES YES GE Medical, Actelion United Therapeutics, Actelion Pharmaceuticals Pharmaceuticals Abraham Jacob NO YES Abraham JoEllyn Moore NO YES Abraham Maria Roselle NO YES Abraham Theodore P. -

400 Editor RABBI SHIMON HELINGER

ב"ה למען ישמעו • פרשת תצוה • 400 EDITOR RABBI SHIMON HELINGER PURIM A POTENT DAY INTENSE REJOICING The Rebbe once said: It’s obvious that we must distance ourselves entirely The Zohar notes that Purim is similar to Yom We read in the Gemara that on Purim one must drink from anything negative (“cursed be Haman”), HaKipurim. This means that what is accomplished “until he cannot differentiate (“ad d’lo yada”) between and seek to treasure and embrace all good things on Yom Kippur by fasting can be accomplished ‘cursed be Haman’ and ‘blessed be Mordechai.’ ” (“blessed be Mordechai”). That applies at any time. on Purim by rejoicing. Furthermore, the very The Gemara relates a story of two amoraim, Rabbah The unique aspect of Purim is that we can accomplish name Kipurim (“like Purim”), implies that Purim and Rav Zeira, who had their Purim seuda together, this by allowing our neshama to express itself freely. is the greater Yom-Tov, impacting a person sharing profound secrets of the Torah over a This kind of avoda is superior to serving HaShem by more powerfully. number of cups of wine. However, Rav Zeira was so means of conscious thought (yada). Indeed, in this Indeed, Chazal teach that when Moshiach comes, all overwhelmed by the intense kedusha of Rabbah’s kind of avoda we can resemble the Yidden at the the Yomim-Tovim will cease to exist; only the Yom- revelations that his neshama left his body. time of the Purim story who, when the inner power Tov of Purim will remain. Chassidus explains that of their neshamos surfaced, fulfilled all the mitzvos the joy and holiness of Purim are so great, that even faithfully, even to the point of mesiras nefesh. -

Modern Approaches to the Talmud: Sacha Stern | University College London

09/29/21 HEBR7411: Modern approaches to the Talmud: Sacha Stern | University College London HEBR7411: Modern approaches to the View Online Talmud: Sacha Stern Albeck, Chanoch, Mavo La-Talmudim (Tel-Aviv: Devir, 1969) Alexander, Elizabeth Shanks, Transmitting Mishnah: The Shaping Influence of Oral Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006) Amit, Aaron, Makom She-Nahagu: Pesahim Perek 4 (Yerushalayim: ha-Igud le-farshanut ha-Talmud, 2009), Talmud ha-igud Ba’adani, Netanel, Hayu Bodkin: Sanhedrin Perek 5 (Yerushalayim: ha-Igud le-farshanut ha-Talmud, 2012), Talmud ha-igud Bar-Asher Siegal, Michal, Early Christian Monastic Literature and the Babylonian Talmud (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013) Benovitz, Moshe, Lulav va-Aravah ve-Hahalil: Sukkah Perek 4-5 (Yerushalayim: ha-Igud le-farshanut ha-Talmud, 2013), Talmud ha-igud ———, Me-Ematai Korin et Shema: Berakhot Perek 1 (Yerushalayim: ha-Igud le-farshanut ha-Talmud, 2006), Talmud ha-igud Brody, Robert, Mishnah and Tosefta Studies, First edition, July 2014 (Jerusalem: The Hebrew university, Magnes press, 2014) ———, The Geonim of Babylonia and the Shaping of Medieval Jewish Culture, Paperback ed., with a new preface and an updated bibliography (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013) Carmy, Shalom, Modern Scholarship in the Study of Torah: Contributions and Limitations (Northvale, N.J.: J. Aronson, 1996), The Orthodox Forum series Chernick, Michael L., Essential Papers on the Talmud (New York: New York University Press, 1994), Essential papers on Jewish studies Daṿid Halivni, Meḳorot U-Masorot (Nashim), ha-Mahadurah ha-sheniyah (Ṭoronṭo, Ḳanadah: Hotsaʼat Otsarenu) ———, Meḳorot U-Masorot: Seder Moʼed (Yerushalayim: Bet ha-Midrash le-Rabanim be-Ameriḳah be-siṿuʻa Keren Moshe (Gusṭaṿ) Ṿortsṿayler, 735) ‘dTorah.com’ <http://dtorah.com/> 1/5 09/29/21 HEBR7411: Modern approaches to the Talmud: Sacha Stern | University College London Epstein, J. -

Source Sheet on Prohibitions on Loshon Ha-Ra and Motzi Shem Ra and Disclosing Another’S Confidential Secrets and Proper Etiquette for Speech

Source Sheet on Prohibitions on Loshon ha-ra and motzi shem ra and disclosing another’s confidential secrets and Proper Etiquette for Speech Deut. 24:9 - "Remember what the L-rd your G-d did unto Miriam by the way as you came forth out of Egypt." Specifically, she spoke against her brother Moses. Yerushalmi Berachos 1:2 Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai said, “Had I been at Mount Sinai at the moment when the torah was given to Yisrael I would have demanded that man should have been created with two mouths- one for Torah and prayer and other for mundane matters. But then I retracted and exclaimed that if we fail and speak lashon hara with only one mouth, how much more so would we fail with two mouths Bavli Arakhin15b R. Yochanan said in the name of R.Yosi ben Zimra: He who speaks slander, is as though he denied the existence of the Lord: With out tongue will we prevail our lips are our own; who is lord over us? (Ps.12:5) Gen R. 65:1 and Lev.R. 13:5 The company of those who speak slander cannot greet the Presence Sotah 5a R. Hisda said in the name of Mar Ukba: When a man speaks slander, the holy one says, “I and he cannot live together in the world.” So scripture: “He who slanders his neighbor in secret…. Him I cannot endure” (Ps. 101:5).Read not OTO “him’ but ITTO “with him [I cannot live] Deut.Rabbah 5:10 R.Mana said: He who speaks slander causes the Presence to depart from the earth below to heaven above: you may see foryourselfthat this is so.Consider what David said: “My soul is among lions; I do lie down among them that are aflame; even the sons of men, whose teeth are spears and arrows, and their tongue a sharp sword” (Ps.57:5).What follows directly ? Be Thou exalted O God above the heavens (Ps.57:6) .For David said: Master of the Universe what can the presence do on the earth below? Remove the Presence from the firmament. -

A Hebrew Elegy on the York Martyrs of 1190

A Hebrew Elegy on the York Martyrs of 1190 By Cecil Roth, M.A., D.Phil., F.R.Hist.S. It is generally known that the Hebrew sources for the history of the Jews in medieval England are extremely sparse. The chronicler Ephraim of Bonn gives 1 a poignant, but not in every respect accurate, account of themassacres of 1189-90 : and historians of a later generation reproduce a legendary story of the Expulsion of theJews by Edward I, partly deriving as it seems from a lostwork of the polemist and grammarian Profiat Duran and partly from the Fortalitium Fidei of the Franciscan Alfonso de Espana.2 Except for one or two oblique allusions, this is almost all. Any new material that comes to light is therefore all the more valuable. A century ago, Zunz called attention to two Hebrew elegies on the English massacres at the beginning of the reign ofRichard I. One of them, by R. Menachem ben Jacob, was presented (as far as the portion relating to England was concerned) by Solomon Schechter at the very first ordinary meeting of the Jewish Historical Society of England, and occupies pride of place after the Presidential Address in the earliest volume of its Transactions.* It is heartrending, turgid, and not particularly informative, being conceived in general terms which might apply to any other 4 medieval massacre. It is all themore surprising that Zunz's further indication has not hitherto been followed up, as I discovered not long since tomy great astonishment. It is true that he no exact information as to the source, which he indicates " gives " vaguely as a French Manuscript ; but at the time when Schechter wrote, so soon after theMaster's death, and while Joseph Jacobs was still engaged in collecting every scrap of evidence relating to the Jews of Angevin England, itwould not have been difficult to trace the requisite information. -

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿavoda Zara By

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara By Mira Beth Wasserman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley in Jewish Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair Professor Chana Kronfeld Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Kenneth Bamberger Spring 2014 Abstract The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara by Mira Beth Wasserman Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair In this dissertation, I argue that there is an ethical dimension to the Babylonian Talmud, and that literary analysis is the approach best suited to uncover it. Paying special attention to the discursive forms of the Talmud, I show how juxtapositions of narrative and legal dialectics cooperate in generating the Talmud's distinctive ethics, which I characterize as an attentiveness to the “exceptional particulars” of life. To demonstrate the features and rewards of a literary approach, I offer a sustained reading of a single tractate from the Babylonian Talmud, ʿAvoda Zara (AZ). AZ and other talmudic discussions about non-Jews offer a rich resource for considerations of ethics because they are centrally concerned with constituting social relationships and with examining aspects of human experience that exceed the domain of Jewish law. AZ investigates what distinguishes Jews from non-Jews, what Jews and non- Jews share in common, and what it means to be a human being. I read AZ as a cohesive literary work unified by the overarching project of examining the place of humanity in the cosmos. -

Designing the Talmud: the Origins of the Printed Talmudic Page

Marvin J. Heller The author has published Printing the Talmud: A History of the Earliest Printed Editions of the Talmud. DESIGNING THE TALMUD: THE ORIGINS OF THE PRINTED TALMUDIC PAGE non-biblical Jewish work,i Its redaction was completed at the The Talmudbeginning is indisputablyof the fifth century the most and the important most important and influential commen- taries were written in the middle ages. Studied without interruption for a milennium and a half, it is surprising just how significant an eftèct the invention of printing, a relatively late occurrence, had upon the Talmud. The ramifications of Gutenberg's invention are well known. One of the consequences not foreseen by the early practitioners of the "Holy Work" and commonly associated with the Industrial Revolution, was the introduction of standardization. The spread of printing meant that distinct scribal styles became generic fonts, erratic spellngs became uni- form and sequential numbering of pages became standard. The first printed books (incunabula) were typeset copies of manu- scripts, lacking pagination and often not uniform. As a result, incunabu- la share many characteristics with manuscripts, such as leaving a blank space for the first letter or word to be embellshed with an ornamental woodcut, a colophon at the end of the work rather than a title page, and the use of signatures but no pagination.2 The Gutenberg Bibles, for example, were printed with blank spaces to be completed by calligra- phers, accounting for the varying appearance of the surviving Bibles. Hebrew books, too, shared many features with manuscripts; A. M. Habermann writes that "Conats type-faces were cast after his own handwriting, . -

Miriyam Goldman OA Thesis 9Dec20.Pdf (247.7Kb)

The Living Stone: The Talmudic Paradox of the Seventh Month Gestational Viability vs. the Eighth Month Non-Viability Presented to the S. Daniel Abraham Honors Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Completion of the Program Stern College for Women Yeshiva University December 9, 2020 Miriyam A. Goldman Mentor: Rabbi Dr. Richard Weiss, Biology Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………….…. 4 Background to Pregnancy ……………………………………………………………………… 5 Talmudic Sources on the Dilemma ……………………………………………………………. 6 Meforshim on the Dilemma ……………………………………………………………………. 9 Secular Sources of the Dilemma ………………………………………………………………. 11 The Significance of Hair and Nails in Terms of Viability……………………………….……... 14 The Definition of Nefel’s Impact on Viability ……………………………………………….. 17 History of Premature Survival ………………………………………………………………… 18 Statistics on Prematurity ………………………………………………………………………. 19 Developmental Differences Between Seventh and Eighth Months ……………………….…. 20 Contemporary Talmudic Balance of the Dilemma..…………………………………….…….. 22 Contemporary Secular Balance of the Dilemma .……………………………………….…….. 24 Evaluation of Talmudic Accreditation …………………………………………………..…...... 25 Interviews with Rabbi Eitan Mayer, Rabbi Daniel Stein, and Rabbi Dr. Richard Weiss .…...... 27 Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………….…. 29 References…..………………………………………………………………………………..… 34 2 Abstract This paper reviews the viability of premature infants, specifically the halachic status of those born in -

Hebrew Printed Books and Manuscripts

HEBREW PRINTED BOOKS AND MANUSCRIPTS .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. SELECTIONS FROM FROM THE THE RARE BOOK ROOM OF THE JEWS’COLLEGE LIBRARY, LONDON K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY TUESDAY, MARCH 30TH, 2004 K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art Lot 51 Catalogue of HEBREW PRINTED BOOKS AND MANUSCRIPTS . SELECTIONS FROM THE RARE BOOK ROOM OF THE JEWS’COLLEGE LIBRARY, LONDON Sold by Order of the Trustees The Third Portion (With Additions) To be Offered for Sale by Auction on Tuesday, 30th March, 2004 (NOTE CHANGE OF SALE DATE) at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand on Sunday, 28th March: 10 am–5:30 pm Monday, 29th March: 10 am–6 pm Tuesday, 30th March: 10 am–2:30 pm Important Notice: The Exhibition and Sale will take place in our new Galleries located at 12 West 27th Street, 13th Floor, New York City. This Sale may be referred to as “Winnington” Sale Number Twenty Three. Catalogues: $35 • $42 (Overseas) Hebrew Index Available on Request KESTENBAUM & COMPANY Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 12 West 27th Street, 13th Floor, New York, NY 10001 ¥ Tel: 212 366-1197 ¥ Fax: 212 366-1368 E-mail: [email protected] ¥ World Wide Web Site: www.kestenbaum.net K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager & Client Accounts: Margaret M. Williams Press & Public Relations: Jackie Insel Printed Books: Rabbi Belazel Naor Manuscripts & Autographed Letters: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Ceremonial Art: Aviva J. Hoch (Consultant) Catalogue Photography: Anthony Leonardo Auctioneer: Harmer F. Johnson (NYCDCA License no. 0691878) ❧ ❧ ❧ For all inquiries relating to this sale, please contact: Daniel E. -

Mishnah: the New Scripture Territories in the East

176 FROM TEXT TO TRADITION in this period was virtually unfettered. The latter restriction seems to have been often compromised. Under the Severan dynasty (193-225 C.E.) Jewish fortunes improved with the granting of a variety of legal privileges culminating in full Roman citizenship for Jews. The enjoyment of these privileges and the peace which Jewry enjoyed in the Roman Empire were·· interrupted only by the invasions by the barbarians in the West 10 and the instability and economic decline they caused throughout the empire, and by the Parthian incursions against Roman Mishnah: The New Scripture territories in the East. The latter years of Roman rule, in the aftermath of the Bar Kokhba Revolt and on the verge of the Christianization of the empire, were extremely fertile ones for the development of . The period beginning with the destruction (or rather, with the Judaism. It was in this period that tannaitic Judaism came to its restoration in approximately 80 C.E.) saw a fundamental change final stages, and that the work of gathering its intellectual in Jewish study and learning. This was the era in which the heritage, the Mishnah, into a redacted collection began. All the Mishnah was being compiled and in which many other tannaitic suffering and the fervent yearnings for redemption had culmi traditions were taking shape. The fundamental change was that nated not in a messianic state, but in a collection of traditions the oral Torah gradually evolved into a fixed corpus of its own which set forth the dreams and aspirations for the perfect which eventually replaced the written Torah as the main object holiness that state was to engender. -

The Greatest Mirror: Heavenly Counterparts in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha

The Greatest Mirror Heavenly Counterparts in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha Andrei A. Orlov On the cover: The Baleful Head, by Edward Burne-Jones. Oil on canvas, dated 1886– 1887. Courtesy of Art Resource. Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2017 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY www.sunypress.edu Production, Dana Foote Marketing, Fran Keneston Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Orlov, Andrei A., 1960– author. Title: The greatest mirror : heavenly counterparts in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha / Andrei A. Orlov. Description: Albany, New York : State University of New York Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016052228 (print) | LCCN 2016053193 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438466910 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438466927 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Apocryphal books (Old Testament)—Criticism, interpretation, etc. Classification: LCC BS1700 .O775 2017 (print) | LCC BS1700 (ebook) | DDC 229/.9106—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016052228 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For April DeConick . in the season when my body was completed in its maturity, there imme- diately flew down and appeared before me that most beautiful and greatest mirror-image of myself.