Competing Saints in Late Medieval Padua*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor RESEARCH IN MEDIEVAL CULTURE Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Medieval Institute Publications is a program of The Medieval Institute, College of Arts and Sciences Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor MEDIEVAL INSTITUTE PUBLICATIONS Western Michigan University Kalamazoo Copyright © 2015 by the Board of Trustees of Western Michigan University All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Taylor, Robert A. (Robert Allen), 1937- Bibliographical guide to the study of the troubadours and old Occitan literature / Robert A. Taylor. pages cm Includes index. Summary: "This volume provides offers an annotated listing of over two thousand recent books and articles that treat all categories of Occitan literature from the earli- est enigmatic texts to the works of Jordi de Sant Jordi, an Occitano-Catalan poet who died young in 1424. The works chosen for inclusion are intended to provide a rational introduction to the many thousands of studies that have appeared over the last thirty-five years. The listings provide descriptive comments about each contri- bution, with occasional remarks on striking or controversial content and numerous cross-references to identify complementary studies or differing opinions" -- Pro- vided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-58044-207-7 (Paperback : alk. paper) 1. Provençal literature--Bibliography. 2. Occitan literature--Bibliography. 3. Troubadours--Bibliography. 4. Civilization, Medieval, in literature--Bibliography. -

Andrea-Bianka Znorovszky

10.14754/CEU.2016.06 Doctoral Dissertation Between Mary and Christ: Depicting Cross-Dressed Saints in the Middle Ages (c. 1200-1600) By: Andrea-Bianka Znorovszky Supervisor(s): Gerhard Jaritz Marianne Sághy Submitted to the Medieval Studies Department, and the Doctoral School of History (HUNG doctoral degree) Central European University, Budapest of in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Medieval Studies, and for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History(HUNG doctoral degree) CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2016 10.14754/CEU.2016.06 I, the undersigned, Andrea-Bianka Znorovszky, candidate for the PhD degree in Medieval Studies, declare herewith that the present dissertation is exclusively my own work, based on my research and only such external information as properly credited in notes and bibliography. I declare that no unidentified and illegitimate use was made of the work of others, and no part of the thesis infringes on any person’s or institution’s copyright. I also declare that no part of the thesis has been submitted in this form to any other institution of higher education for an academic degree. Budapest, 07 June 2016. __________________________ Signature CEU eTD Collection i 10.14754/CEU.2016.06 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the dawn, after a long, perilous journey, when, finally, the pilgrim got out from the maze and reached the Holy Land, s(he) is still wondering on the miraculous surviving from beasts, dragons, and other creatures of the desert who tried to stop its travel. Looking back, I realize that during this entire journey I was not alone, but others decided to join me and, thus, their wisdom enriched my foolishness. -

Europa E Italia. Studi in Onore Di Giorgio Chittolini

21 VENICE AND THE VENETO DURING THE RENAISSANCE THE LEGACY OF BENJAMIN KOHL Edited by Michael Knapton, John E. Law, Alison A. Smith thE LEgAcy of BEnJAMin KohL BEnJAMin of LEgAcy thE rEnAiSSAncE thE during VEnEto thE And VEnicE Smith A. Alison Law, E. John Knapton, Michael by Edited Benjamin G. Kohl (1938-2010) taught at Vassar College from 1966 till his retirement as Andrew W. Mellon Professor of the Humanities in 2001. His doctoral research at The Johns Hopkins University was directed by VEnicE And thE VEnEto Frederic C. Lane, and his principal historical interests focused on northern Italy during the Renaissance, especially on Padua and Venice. during thE rEnAiSSAncE His scholarly production includes the volumes Padua under the Carrara, 1318-1405 (1998), and Culture and Politics in Early Renaissance Padua thE LEgAcy of BEnJAMin KohL (2001), and the online database The Rulers of Venice, 1332-1524 (2009). The database is eloquent testimony of his priority attention to historical sources and to their accessibility, and also of his enthusiasm for collaboration and sharing among scholars. Michael Knapton teaches history at Udine University. Starting from Padua in the fifteenth century, his research interests have expanded towards more general coverage of Venetian history c. 1300-1797, though focusing primarily on the Terraferma state. John E. Law teaches history at Swansea University, and has also long served the Society for Renaissance Studies. Research on fifteenth- century Verona was the first step towards broad scholarly investigation of Renaissance Italy, including its historiography. Alison A. Smith teaches history at Wagner College, New York. A dissertation on sixteenth-century Verona was the starting point for research interests covering the social history of early modern Italy, gender, urban elites, sociability and musical academies. -

Dipartimento Di Discipline Storiche Artistiche Archeologiche E Geografiche Giuseppe Gardoni VESCOVI-PODESTÀ NELL'italia PADAN

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Reti Medievali Open Archive UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI VERONA Dipartimento di Discipline storiche artistiche archeologiche e geografiche Giuseppe Gardoni VESCOVI-PODESTÀ NELL’ITALIA PADANA Libreria Universitaria Editrice Verona 2008 Proprietà Letteraria Riservata @ by Libreria Universitaria Editrice Via dell’Artigliere 3/A - 37129 Verona ISBN: 978-88-89844-27-4 per Andrea e Alessandro INDICE ABBREVIAZIONI………………………………… 5 PREMESSA……………………………………… 7 PARTE PRIMA Vescovi-podestà tra 1180 e 1240…………...…. 21 Capitolo I. Nell’Italia padana 1.1. L’Emilia e la Romagna ………………. 23 1.2. La Lombardia: Brescia e Pavia……….. 32 1.3 La ‘variabile’ dell’Alleluia: frati podestà e (arci)vescovi podestà dal 1233 al 1240………………………. 44 Capitolo II. Vescovi-podestà a Mantova 2.1. Garsendonio………………………….. 54 2.2. Enrico………………… ……………... 57 2.3. Vescovi di Mantova podestà di comuni rurali………………………… 61 Conclusione della parte I……………………… 77 PARTE SECONDA Un caso emblematico: Guidotto da Correggio vescovo-podestà di Mantova nel 1233………... 93 Capitolo I. “Pro Ecclesia Romana” 1.1. Da canonico a vescovo………………. 95 1.2. Il sostegno alla politica pontificia…... 104 4 Vescovi-podestà nell’Italia padana 1.3. “Episcopus et potestas”…………… 113 Capitolo II. “In caulis ovium Christi pastor” 2.1. Le istituzioni ecclesiastiche e la vita religiosa…………………….. 133 2.2. La “cura animarum”………………. 147 2.3. I Mendicanti e la lotta all’eresia…... 156 2.4. La difesa della libertas Ecclesiae…. 165 Capitolo III. “Bibit calicem passionis” 3.1. L’assassinio……………………….. 176 3.2. ‘Martire’ ma non santo……………. 179 Conclusione della parte II…………………. -

Introduction: Castles

Introduction: Castles Between the 9th and 10th centuries, the new invasions that were threatening Europe, led the powerful feudal lords to build castles and fortresses on inaccessible heights, at the borders of their territories, along the main roads and ri- vers’ fords, or above narrow valleys or near bridges. The defense of property and of the rural populations from ma- rauding invaders, however, was not the only need during those times: the widespread banditry, the local guerrillas between towns and villages that were disputing territori- es and powers, and the general political crisis, that inve- sted the unguided Italian kingdom, have forced people to seek safety and security near the forts. Fortified villages, that could accommodate many families, were therefore built around castles. Those people were offered shelter in exchange of labor in the owner’s lands. Castles eventually were turned into fortified villages, with the lord’s residen- ce, the peasants homes and all the necessary to the community life. When the many threats gradually ceased, castles were built in less endangered places to bear witness to the authority of the local lords who wanted to brand the territory with their power, which was represented by the security offered by the fortress and garrisons. Over the centuries, the castles have combined several functions: territory’s fortress and garrison against invaders and internal uprisings ; warehouse to gather and protect the crops; the place where the feudal lord administered justice and where horsemen and troops lived. They were utilised, finally, as the lord’s and his family residence, apartments, which were gradually enriched, both to live with more ease, and to make a good impression with friends and distinguished guests who often stayed there. -

Baone Anc Castelfranco, Italy

REPORT ON STUDY VISIT, TRAINING AND KNOWLEDGE EXCHANGE SEMINAR IN VILLA BEATRICE D’ESTE (BAONE – Version 1 PADUA) AND CASTELFRANCO 04/2018 VENETO (TREVISO), ITALY D.T3.2.2 D.T3.5.1 D.T4.6.1 Table of Contents REPORT ON STUDY VISIT IN VILLA BEATRICE D’ESTE (BAONE - PADUA) on 07/03/2018…………….…. Page 3 1. ORGANISATIONAL INFORMATION REGARDING THE STUDY VISIT ........................................................................... 3 1.1. Agenda of study visit to Villa Beatrice d’Este, 07/03/2018 ................................................................................... 3 1.2. List of study visit participants .............................................................................................................................. 5 2. HISTORY OF VILLA BEATRICE D’ESTE ....................................................................................................................... 6 2.1. History of the property and reconstruction stages ............................................................................................... 6 2.2. Adaptations and conversions of some parts of the monastery............................................................................. 8 3. Characteristics of the contemporarily existing complex ........................................................................................ 12 3.1. Villa Beatrice d’Este and the surrounding areas - the current condition Characteristics of the area where the ruin is located ......................................................................................................................................................... -

A British Reflection: the Relationship Between Dante's Comedy and The

A British Reflection: the Relationship between Dante’s Comedy and the Italian Fascist Movement and Regime during the 1920s and 1930s with references to the Risorgimento. Keon Esky A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. University of Sydney 2016 KEON ESKY Fig. 1 Raffaello Sanzio, ‘La Disputa’ (detail) 1510-11, Fresco - Stanza della Segnatura, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican. KEON ESKY ii I dedicate this thesis to my late father who would have wanted me to embark on such a journey, and to my partner who with patience and love has never stopped believing that I could do it. KEON ESKY iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis owes a debt of gratitude to many people in many different countries, and indeed continents. They have all contributed in various measures to the completion of this endeavour. However, this study is deeply indebted first and foremost to my supervisor Dr. Francesco Borghesi. Without his assistance throughout these many years, this thesis would not have been possible. For his support, patience, motivation, and vast knowledge I shall be forever thankful. He truly was my Virgil. Besides my supervisor, I would like to thank the whole Department of Italian Studies at the University of Sydney, who have patiently worked with me and assisted me when I needed it. My sincere thanks go to Dr. Rubino and the rest of the committees that in the years have formed the panel for the Annual Reviews for their insightful comments and encouragement, but equally for their firm questioning, which helped me widening the scope of my research and accept other perspectives. -

Guide to Places of Interest

Guide to places of interest Lido di Jesolo - Venezia Cortina Oderzo Portogruaro Noventa di Piave Treviso San Donà di Piave Caorle Altino Eraclea Vicenza Jesolo Eraclea Mare Burano Cortellazzo Lido di Jesolo Dolo Venezia Verona Padova Cavallino Mira Cà Savio Chioggia Jesolo and the hinterland. 3 Cathedrals and Roman Abbeys . 10 Visits to markets Concordia Sagittaria, Summaga and San Donà di Piave Venice . 4 From the sea to Venice’s Lagoon . 11 St Mark’s Square, the Palazzo Ducale (Doge’s Palace) and the Caorle, Cortellazzo, Treporti and Lio Piccolo Rialto Bridge The Marchland of Treviso The Islands of the Lagoon . 5 and the city of Treviso . 12 Murano, Burano and Torcello Oderzo, Piazza dei Signori and the Shrine of the Madonna of Motta Verona and Lake Garda. 6 Padua . 13 Sirmione and the Grottoes of Catullo Scrovegni Chapel and Piazza delle Erbe (Square of Herbs) The Arena of Verona and Opera . 7 Vicenza . 14 Operatic music The Olympic Theatre and the Ponte Vecchio (Old Bridge) of Bas- sano del Grappa Cortina and the Dolomites . 8 The three peaks of Lavaredo and Lake Misurina Riviera del Brenta . 15 Villas and gardens The Coastlines . 9 Malamocco, Pellestrina, Chioggia 2 Noventa di Piave Treviso San Donà di Piave Eraclea Caorle Jesolo Eraclea Mare Lido di Jesolo Cortellazzo Cavallino Jesolo and the hinterland The lagoon with its northern appendage wends its way into the area of Jesolo between the river and the cultivated countryside. The large fishing valleys of the northern lagoon extend over an area that is waiting to be explored. Whatever your requirements, please discuss these with our staff who will be more than happy to help. -

Curriculum Accademico

Antonio Rigon (L’Aquila, 16-1-1941) Prof. di prima fascia, SSD MSTO/01 (Storia medievale): in pensione dal 1° ottobre 2011 Curriculum accademico Dal 1990 professore di prima fascia nel Settore Scientifico Disciplinare MSTO/01 (Storia medioevale). Ha insegnato Storia medioevale, Storia delle Venezie e Storia della cultura e delle mentalità nel medioevo nelle Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia e di Magistero dell’Università di Padova Visiting scholar presso il Department of History dell’Università di Berkeley (1993). Nell’Ateneo di Padova è stato direttore del Dipartimento di Storia dal 1992 al 1998; presidente del Corso di laurea in Storia dal 1998 al 2001; coordinatore del Dottorato di ricerca in Storia del Cristianesimo (già Dottorato di storia della Chiesa medievale e dei movimenti ereticali) dal 1997 al 2003; direttore della Scuola di Dottorato in Scienze storiche dal 2004 al 2007. Responsabile nazionale e locale di vari PRIN (da ultimo PRIN 2009, Percezione e rappresentazione della Terrasanta e dell’Oriente mediterraneo nelle fonti agiografiche, cronachistiche, odeporiche, omiletiche e testamentarie di area italiana secoli XII-XV) Presiede il Comitato scientifico dell’Istituto superiore di Studi medievali “Cecco d’Ascoli” e la Giuria del Premio internazionale Ascoli Piceno. E’ inoltre direttore del Centro interuniversitario di studi Francescani (Università di Perugia, Padova, Verona, Milano-Cattolica, Milano-Statale, Roma Tre, Macerata, Chieti, Napoli “Federico II”),. É membro del Consiglio direttivo dell’Istituto storico italiano per il Medio Evo, del Consiglio direttivo della Società internazionale di Studi francescani, della Commissione ministeriale per l’edizione nazionale delle fonti francescane, del Consiglio direttivo della Fondazione mons. Michele Maccarrone per la Storia della Chiesa in Italia. -

Cortenuova 1237

Cortenuova 1237 INTRODUCTION Cortenuova 1237 is based on the conflict between Guelphs and Ghibellines in XIII century Italy. The Ghi- bellines, led by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, are attempting to restore Imperial power south of the Alps while Guelphs, let by Pope Gregory IX, are opposing restoration of imperial power in the north and are trying to break Emperor’s allies in Italy. Both players attempt to capture cities and castles of Italy, Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica. The Ghibelline player starts with a powerful army in the north but must conduct many sieges, giving time to his opponents to organise a resistance. A smaller army is in the south but lacks proper leadership. Lack of communication between north and south is an issue for Imperial player. The Guelph player starts with his armies spread out over Italy and must first concentrate his forces in order to slow down Emperor’s armies. After the Emperor has been stopped the central position of Guelph hol- dings allows for a number of possible avenues of advance. The game’s event cards allow full replay ability thanks to the numerous various situations that they create on the diplomatic, military, political or economical fields. Estimated Playing Time: 3h30 DURATION Favored Side: None Hardest to play: None Cortenuova 1237 lasts 24 turns each representing about two months, between August 1237 and August 1241. TheGhibelline player always goes before the Guelph player. FORCES The Ghibelline player controls Holy Roman Empire (golden), Ezzelino da Romano’s dominions (green), Kingdom of Sicily (gray), Republic of Pisa (dark red), Republic of Siena (black) and other Ghibelline (red) units. -

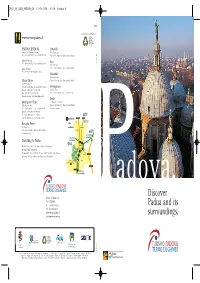

Discover Padua and Its Surroundings

2647_05_C415_PADOVA_GB 17-05-2006 10:36 Pagina A Realized with the contribution of www.turismopadova.it PADOVA (PADUA) Cittadella Stazione FS / Railway Station Porta Bassanese Tel. +39 049 8752077 - Fax +39 049 8755008 Tel. +39 049 9404485 - Fax +39 049 5972754 Galleria Pedrocchi Este Tel. +39 049 8767927 - Fax +39 049 8363316 Via G. Negri, 9 Piazza del Santo Tel. +39 0429 600462 - Fax +39 0429 611105 Tel. +39 049 8753087 (April-October) Monselice Via del Santuario, 2 Abano Terme Tel. +39 0429 783026 - Fax +39 0429 783026 Via P. d'Abano, 18 Tel. +39 049 8669055 - Fax +39 049 8669053 Montagnana Mon-Sat 8.30-13.00 / 14.30-19.00 Castel S. Zeno Sun 10.00-13.00 / 15.00-18.00 Tel. +39 0429 81320 - Fax +39 0429 81320 (sundays opening only during high season) Teolo Montegrotto Terme c/o Palazzetto dei Vicari Viale Stazione, 60 Tel. +39 049 9925680 - Fax +39 049 9900264 Tel. +39 049 8928311 - Fax +39 049 795276 Seasonal opening Mon-Sat 8.30-13.00 / 14.30-19.00 nd TREVISO 2 Sun 10.00-13.00 / 15.00-18.00 AIRPORT (sundays opening only during high season) MOTORWAY EXITS Battaglia Terme TOWNS Via Maggiore, 2 EUGANEAN HILLS Tel. +39 049 526909 - Fax +39 049 9101328 VENEZIA Seasonal opening AIRPORT DIRECTION TRIESTE MOTORWAY A4 Travelling to Padua: DIRECTION MILANO VERONA MOTORWAY A4 AIRPORT By Air: Venice, Marco Polo Airport (approx. 60 km. away) By Rail: Padua Train Station By Road: Motorway A13 Padua-Bologna: exit Padua Sud-Terme Euganee. Motorway A4 Venice-Milano: exit Padua Ovest, Padua Est MOTORWAY A13 DIRECTION BOLOGNA adova. -

Per L'attribuzione Del Carme Scaliger Interea Canis: Aspetti Stilistici E Metrici

Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Filologia Moderna Classe LM-14 Tesi di Laurea Per l’attribuzione del carme Scaliger interea Canis: aspetti stilistici e metrici Relatore Laureando Prof. Giovanna Maria Gianola Silvia Berti n° matr.1104222 / LMFIM Anno Accademico 2016 / 2017 1 INDICE PREMESSA 3 LA VITA E LE OPERE 5 DE SCALIGERORUM ORIGINE 11 1. Composizione e tradizione 13 2. Lo studio del lessico 15 2.1 Ezzelino e i proceres 15 2.2 I conflitti 24 2.3 Le vittime 28 2.4 I della Scala 32 3. Retorica e sintassi 45 4. Uno sguardo d’insieme 59 DOPO IL DE SCALIGERORUM ORIGINE: OSSERVAZIONI SULL’HISTORIA 63 SCALIGER INTEREA CANIS 71 1. Composizione e tradizione 73 2. Lo studio del lessico 79 2.1 I personaggi 79 2.2 I conflitti 88 2.3 Le vittime 90 2.4 La toponomastica 92 3. Retorica e sintassi 99 ASPETTI METRICI 105 1. Metodo e strumenti 107 2. Gli schemi metrici 109 3. La sinalefe 113 4. Le cesure 117 2 CONCLUSIONI 121 TRADUZIONE 125 APPENDICE 149 BIBLIOGRAFIA 177 3 PREMESSA «La volta che Lila e io decidemmo di salire per le scale buie che portavano, gradino dietro gradino, rampa dietro rampa, fino alla porta dell’appartamento di don Achille, cominciò la nostra amicizia.»1 E cominciò così anche uno dei casi editoriali più discussi dell’ultimo quarto di secolo. L’autrice della tetralogia L’amica geniale, infatti, si è da allora celata dietro lo pseudonimo di Elena Ferrante.