Rebuilding St. Kunibert: Artistic Integration, Patronage, and Institutional Identities in Thirteenth-Century Cologne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kirby Catalogue Part 8 1891-1895

Archival list The Kirby Collection Catalogue Irish College Rome ARCHIVES PONTIFICAL IRISH COLLEGE, ROME Code Date Description and Extent KIR/ 1890 / 494 circa 1890 Holograph letter from Sr. Mary, Rome, to Kirby: Writer thanks Kirby for consenting to be their confessor. Query as to steps to be taken. [see KIR/1890/316] ['Sr. Mary' would appear to be the Foundress of the Little Company of Mary.] 3pp 495 31 December Holograph letter from J.J. Farr, Chettendale, Marrickville, 1890 to Kirby: Personal letter. [Although this letter is dated 'December 31st 1890', the postscript which states 'All well but very hot here' is dated January 5th 1891.] 1p 1 1 January Holograph letter from Sr. M. Peter Frances O'Reilly, 1891 Lisbon, to Kirby: Convent news. Sisters M. de Ricci and Martha died during 1890. School has fallen off considerably of late years, probably due to number of schools now in the country and 'rage amongst the higher class for foreign governesses'. Requests Pope's blessing on 'his Irish children in Bon Successo, Lisbon' and a special one on the writer who celebrates Golden Jubilee of her profession on 5 October of present year. Necessary to re-open novitiate to admit 2 'promising novices', the one French and the other from Loanda, a former pupil'. 4pp 2 1 January Holograph letter from Sr. M. Ignatius Walsh, Yarrawonga, 1891 Victoria, to Kirby: Personal letter. 4pp 3 1 January Holograph letter from Sr. Mary A. Beckett, Birr, to Kirby: 1891 Thanks Kirby for painting of Our Lady of Mercy, which writer has had framed in Dublin and erected in their own chapel 'in time for St. -

The Lives of the Saints

Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924098140746 3 1924 098 140 746 In compliance with current copyright law, Cornell University Library produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1992 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 2004 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY »i< ^ THE ILi'Qts of tt)e ^atnts; REV. S. BARING-GOULD SIXTEEN VOLUMES VOLUME THE SECOND ^ ^ THE EEPOSE IN EGYPT, WITH DANCING ANGELS. After Luca Cranaoh. Bj the robbery ot the nest In the tree, the painter Ingeniously points to the MaBsooro of the Innocents as to the oouse of the Flight into Egypt J [Pront.-Tol. II. * ^ THE Hities of tl)e ^mt^ BY THE REV. S. BARING-GOULD, M.A. New Edition in i6 Volumes Revised with Introduction and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish and Welsh Saints, and a full Index to the Entire Work ILLUSTRATED BY OVER 400 ENGRAVINGS VOLUME THE SECOND LONDON JOHN C. NIMMO NEW YORK: LONGMANS, GREEN, &- CO. MDCCCXCVIII Prinled by BallaNTYiNE, HANSON &- CO. At tlie Ballantyue Press *- ~>h CONTENTS PAGE S. Auxibius .... 339 S. Abraham „ Aventine of Cha- „ Adalbald 41 teaudun ... 86 ,, Adelheid 140 ,, Aventine of Troyes . 84 „ Adeloga 42 „ Avitus . 138 „ yEmilian 212 Agatha . „ 136 B ,, Aldetrudis „ Alexander 433 S. Baldomer Alnoth . „ 448 Baradatus . „ Amandus 182 Barbatus . SS. Ananias and comp. 412 Belina S. Andrew Corsini 105 Benedict of Aniane „ Angilbert 337 Berach „ Ansbert 246 Berlinda „ Anskar . -

New Museum Sayn Palace English Guided Tour

New Museum Sayn Palace English Guided Tour Welcome to a virtual tour in 14 stages through the Neues Museum Schloss Sayn. You will be personally guided by Alexander Prince zu Sayn-Wittgenstein. Entrance and Museum Shop From the castle tower, Princess Leonilla guides the way to the entrance of the museum in the chapel wing of the palace. In the shop, you will be greeted and advised at the ticket office by our friendly ladies working at the museum. You will find further information on special or themed tours for adults and children of the Sayn Palace or the Butterfly Garden here. You can also purchase a combined ticket, which allows you a discounted visit to both, Sayn Palace and the Butterfly Garden. You can choose to visit these sites on different days within the season. Here you will also find further information about the various attractions and offers of the Sayn Culture Park. A special welcome awaits you from my 100-year-old mother, Princess Marianne, as well as my wife, Princess Gabriela and myself towards the beginning of the tour. Passing the cloakroom you will spot Emperor Wilhelm's quote when he proclaimed after visiting Sayn Palace: "It really is a true fairytale castle”. Further on, you will find portraits of our two "Grandes Dames", the main actors of this exhibition: the princesses Leonilla and Marianne. In this exhibition, the two princesses will tell you the story of their lives lived in the past two centuries - from victorious battles over Napoleon in Russia that gave their family immense wealth and prestige, to social upheaval that forced their return to the ancestral home in Sayn, from their experiences in both world wars causing destruction, privation and reconstruction to a very active social life to the present day. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/26/2021 09:24:42AM Via Free Access Chapter 5 Parish Liturgy

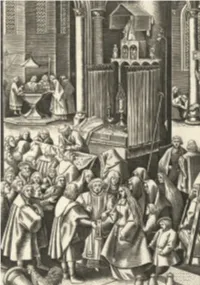

Ruben Suykerbuyk - 9789004433106 Downloaded from Brill.com09/26/2021 09:24:42AM via free access Chapter 5 Parish Liturgy Before it became a pilgrimage destination, Saint Leonard’s church was first and foremost the seat of the parish of Zoutleeuw. As the smallest unit in the ecclesiastical hierarchy, the parish was the level on which Christians practiced and experienced religion on a daily basis. From an administrative point of view, parishes were defined as territorial entities, but they were in fact constituted by the com- munity of its inhabitants, especially in smaller towns or rural areas. Parishioners – the churchwardens among them – had the respon- sibility to care for their weakest neighbors and contribute to the maintenance of the religious infrastructure. Such commitments often ‘fostered a sense of belonging and ownership in the parish community’.1 Its material exponent was the parish church, often the largest stone building, and both literally and figuratively the center of the town. The church was the framework for the proper adminis- tration of the sacraments. Key moments in parishioners’ lives were ritually celebrated here (fig. 80), from baptism of new-born children and their subsequent confirmation and participation in commu- nion at Mass, over marriage, to funeral rites and burial after having received the last rites by the parish priest.2 The stories chaplain Munters recorded in his diary show that, during the sixteenth century, many of these communal rites of pas- sage were subjected to great pressure. Protestants started question- ing and taunting not just religious images, pilgrimages and miracles, but also the core elements of the parish liturgy. -

The Light from the Southern Cross’

A REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS ON THE GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT OF DIOCESES AND PARISHES IN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN AUSTRALIA IMPLEMENTATION ADVISORY GROUP AND THE GOVERNANCE REVIEW PROJECT TEAM REVIEW OF GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT OF DIOCESES AND PARISHES REPORT – STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL Let us be bold, be it daylight or night for us - The Catholic Church in Australia has been one of the epicentres Fling out the flag of the Southern Cross! of the sex abuse crisis in the global Church. But the Church in Let us be fırm – with our God and our right for us, Australia is also trying to fınd a path through and out of this crisis Under the flag of the Southern Cross! in ways that reflects the needs of the society in which it lives. Flag of the Southern Cross, Henry Lawson, 1887 The Catholic tradition holds that the Holy Spirit guides all into the truth. In its search for the path of truth, the Church in Australia And those who are wise shall shine like the brightness seeks to be guided by the light of the Holy Spirit; a light symbolised of the sky above; and those who turn many to righteousness, by the great Constellation of the Southern Cross. That path and like the stars forever and ever. light offers a comprehensive approach to governance issues raised Daniel, 12:3 by the abuse crisis and the broader need for cultural change. The Southern Cross features heavily in the Dreamtime stories This report outlines, for Australia, a way to discern a synodal that hold much of the cultural tradition of Indigenous Australians path: a new praxis (practice) of church governance. -

Book Ii the People of God

BOOK II THE PEOPLE OF GOD PART I CHURCH PERSONNEL TITLE I GENERAL PERSONNEL POLICIES TABLE OF CONTENTS ARCHDIOCESAN EMPLOYEE PHILOSOPHY .........................................................................i GLOSSARY......................................................................................................................................iii §100 EMPLOYMENT RELATIONSHIPS ............................................................................ [100] §101 Employment Status..................................................................................................1 §101.1. Exempt vs. Non-exempt.............................................................................1 §101.2. Full-time/Part-time Status..........................................................................2 §101.3. Independent Contractor vs. Employee.......................................................2 §101.4. Time Sheets and Work Schedules..............................................................4 §101.4.1. Full-Time Exempt Employees ....................................................4 §101.4.2. Full-Time Non-Exempt Employees............................................5 §101.4.2. Full-Time Non-Exempt Employees............................................5 §101.5. Absences and Tardiness.............................................................................6 §102 Civil and Canon Law...............................................................................................6 §200 RECRUITMENT ............................................................................................................ -

A Commentary on the General Instruction of the Roman Missal

A Commentary on the General Instruction of the Roman Missal A Commentary on the General Instruction of the Roman Missal Developed under the Auspices of the Catholic Academy of Liturgy and Cosponsored by the Federation of Diocesan Liturgical Commissions Edited by Edward Foley Nathan D. Mitchell Joanne M. Pierce Foreword by the Most Reverend Donald W. Trautman, S.T.D., S.S.L. Chairman of the Bishops’ Committee on the Liturgy 1993–1996, 2004–2007 A PUEBLO BOOK Liturgical Press Collegeville, Minnesota A Pueblo Book published by Liturgical Press Excerpts from the English translation of Dedication of a Church and an Altar © 1978, 1989, International Committee on English in the Liturgy, Inc. (ICEL); excerpts from the English translation of Documents on the Liturgy, 1963–1979: Conciliar, Papal, and Curial Texts © 1982, ICEL; excerpts from the English translation of Order of Christian Funerals © 1985, ICEL; excerpts from the English translation of The General Instruction of the Roman Missal © 2002, ICEL. All rights reserved. Libreria Editrice Vaticana omnia sibi vindicat iura. Sine ejusdem licentia scripto data nemini licet hunc Lectionarum from the Roman Missal in an editio iuxta typicam alteram, denuo imprimere aut aliam linguam vertere. Lectionarum from the Roman Missal in an editio iuxta typicam alteram—edition iuxta typica, Copyright 1981, Libreria Editrice Vaticana, Città del Vaticano. Excerpts from documents of the Second Vatican Council are from Vatican Council II: The Basic Sixteen Documents, edited by Austin Flannery, © 1996 Costello Publishing Company, Inc. Used with permission. Cover design by David Manahan, OSB. Illustration by Frank Kacmarcik, OblSB. © 2007 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. -

In the Miracle Years, 1956–1966 S

Chapter 4 ORDERING LANDSCAPES AND “LIVING SPACE” IN THE MIRACLE YEARS, 1956–1966 S In the 1957 federal elections, Chancellor Konrad Adenauer’s CDU party and its sister party of Bavaria, the Christian Social Union (CSU), promised “Prosperity for All.” Th eir campaign slogan came from the title of a book ghostwritten that year for Ludwig Erhard, Federal Minister of Economics and architect of West Germany’s “economic miracle.” Th e publication called for economic growth to continue unimpeded to produce national wealth that would benefi t all citizens. Th e country’s remarkable recovery was already evident in industrial production, which had more than doubled since 1945.1 Into the 1970s, with the exception of the recession in 1966–1967, West Germany’s annual rate of economic growth surpassed that of other industrialized nations, leaving its economy in third place behind the US and Japan. Yet the liberal economic policies that contributed to postwar prosperity favored industry and commerce. By the mid 1960s, a minor- ity of the population controlled much of the country’s wealth. But few people protested because unemployment was low at 0.5 percent in 1965, and average dis- posable household incomes rose steadily, quadrupling between 1950 and 1970.2 ”Prosperity for All” was a nice campaign promise. But it was a hard one to keep. In general, the country’s expanding urban areas experienced prosperity more than the rural regions. By 1961, roughly one-third of the country’s 56.5 million people lived in cities having more than 100,000 inhabitants; another 46 percent lived in smaller urban areas. -

Otto Schmidt (1888-1971): Gegner Hitlers Und Intimus Hugenbergs

Otto Schmidt (1888-1971): Gegner Hitlers und Intimus Hugenbergs Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt von Maximilian Terhalle aus Berlin Bonn 2006 Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn. Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Klaus Hildebrand Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Joachim Scholtyseck Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 24. Mai 2006 Diese Dissertation ist auf dem Hochschulschriftenserver der ULB Bonn: http:/hss.ulb.uni-bonn.de/diss_online elektronisch publiziert. Danksagung Unendlicher Dank gilt meinen geliebten Eltern. Ihnen habe ich es zu verdanken, daß ich mich auf diese doktorale Reise begeben durfte. Sie haben mich während der ganzen Zeit unentwegt und auf das herzlichste unterstützt. Sie haben mir das nämliche Brot und vieles mehr gewährt, was in seiner Grenzenlosigkeit kaum in Worte zu fassen ist. Disziplin, eiserne Disziplin, die Härte gegen sich selbst habe ich von Ihnen gelernt. Diese preußische Disziplin war das unersetzbare Movens, das diese Arbeit ermöglicht hat. Meinen Eltern möchte ich an dieser Stelle für Ihre liebevolle Ausdauer danken. Ihnen sei diese Doktorarbeit in Liebe gewidmet. Berlin, den 26. Mai 2006 Wir müssen den vergangenen Generationen das zurückgeben, was sie einmal besaßen, so wie jede Gegenwart es besitzt: die Fülle der möglichen Zukunft, die Ungewißheit, die Freiheit, die Endlichkeit, die Widersprüchlichkeit. Nipperdey, Th., 1933 und die Kontinuität in der deutschen Geschichte, in: ders., Nachdenken über die deutsche Geschichte. Essays, München 2. Aufl. 1986, S. 204 f. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einführung 1 1.1. Gegenstand der Untersuchung und ihre Methode 1 1.2. Quellenlage 8 1.3. Gedruckte Memoirenliteratur 14 1.4. -

PIOTR KRASNY Cultural and National Identity in 18Th-Century Lwow: Three

Originalveröffentlichung in: Kwilecka, Anna u.a. (Hrsg.): Art and national identity in Poland and England, London 1996, S. 41-50 PIOTR KRASNY Cultural and national identity in 18th-century Lwow: three nations - three religions - one art In many ethnically heterogeneous regions of Europe (in the Netherlands, for instance; in Northern Ireland and in the Balkans) national identity was and still is tantamount to religious identity. This has produced specific effects in religious art in these regions. Differences resulting from religious traditions have been doubled by differences in distinct national art traditions. On the other hand, the traditions would often blend, especially after years of coexistence, leading to a certain unification of religious art forms. An interesting example of this process can be seen in the art of Lwow and its region in the 18th century. National and religious identity in Lwow and its region In the Middle Ages Lwow was one of the most important towns in the small Ruthenian D"chy with Halicz as its capital. In the 13th century and at the beginning of the 14th century the duchy was ravaged by Tatars which resulted in its depopulation. When the '°cal dynasty died out in the 1340s, the Polish king Casimir the Great annexed the duchy. new ruler decided to establish Polish settlements and brought in settlers mainly from central Poland. They found their homes mostly in towns, though sometimes they would Set up new villages. Casimir the Great turned the duchy into the Ruthenian province of toe Polish Kingdom and moved its capital to Lwow. Besides being the seat of the Orthodox bishop it soon became also the seat of the Roman Catholic archbishop. -

BCA Schedule

S Legal profession S37WR S Law Law S Legal profession S34 S2 . Primary materials Study in law S34 G * This class is used only under particular jurisdictions; . Student bar associations S34 GGD e.g. English law - Primary materials - Statutes SN2 G. S34 GGM . Moots * See Auxiliary Schedule S2 for instructions. GTC . Law schools (general) H Research in law * For research in the narrow sense of searching the legal . Common subdivisions literature, see S3R D. * These conform to the order of classes 2/9 in Auxiliary * See also Jurisprudence S5A Schedule 1 but with substantial modifications of * Add to S34 H numbers 3/9 following K in K3/K9. notation. H6 . Methodology * Add to S3 numbers 2/3 in Auxiliary Schedule 1 with the additions shown at S33 Y. H6M . Models S3 . General works on the law J Lawyers, attorneys, advocates, practitioners * For works on the formal status, etc. of particular parties S33 B . Dictionaries, encyclopedias or persons in the legal profession. For works on their G . Journals, periodicals, serials practical functioning, see Practice of law S6A. * For indexing & abstracting journals, see S3WH. * Theoretically, BC2 subordinates personnel to their H . Yearbooks specific function (e.g. advocacy). But the varied nature J . Directories, law lists of the tasks undertaken & the possibilities of * Primarily for use in qualifying persons, reorganization which may alter the degree of organizations, etc. specialization of particular personnel make this hard & LR . Conference proceedings fast distinction impracticable. Most of the literature RA . Literature & the law refers to types of personnel, but this should be * Imaginative literature, etc. interpreted as covering their duties as well as their office. -

Dr. Thomas Ingenhoven, LL.M. Partner

Dr. Thomas Ingenhoven, LL.M. Partner VCARD SHARE CONTACT [email protected] FRANKFURT Neue Mainzer Straße 74 60311 Frankfurt am Main, DE T +49 69.71914.3436 F +49 69.71914.3500 Thomas Ingenhoven serves as managing partner of the Frankfurt office and is a member of the firm’s Banking and Leveraged Finance Group. Thomas specializes in acquisition finance, syndicated lending, asset finance and financial derivatives. He advises lenders, sponsors and corporate borrowers on all aspects of leveraged buyouts, financial restructurings, general syndicated lending and asset finance transactions. His recent representations include advising lenders and sponsors/borrowers on: A large number of German and international leveraged buyouts. A range of investment grade and sub-investment grade (cross-over) corporate credit facilities. Syndicated promissory notes for German and foreign issuers. Asset-based financings. Unitranche- and Super Senior credit facilities. Credit facilities embedded in multi-layered capital structures including term loan B-financings, Second Lien, PIK Facilities and capital market instruments. Recognition & Accomplishments Thomas is recognized as one of the leading lawyers by directories as JUVE, Chambers, Legal 500, IFLR 1000, Best Lawyers and Who’s Who Legal for banking and acquisition finance. He studied law at the universities of Tübingen (Dr. jur.), Leiden (The Netherlands) and Cambridge (England) (LL.M.). Thomas is author of the financing chapters of the renowned “Rechtshandbuch Private Equity”, C.H. Beck, Munich, and „Hölters - Handbuch Unternehmenskauf”, Otto Schmidt Verlag, Cologne. He is admitted in Germany (as Rechtsanwalt) and in England and Wales (as Solicitor) and speaks German and English. ADDITIONAL DETAILS EDUCATION University of Tübingen, Dr.