Downloaded from Brill.Com09/26/2021 09:24:42AM Via Free Access Chapter 5 Parish Liturgy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

The Transcriber's Art – #51 Josquin

The Transcriber’s Art – #51 Josquin des Prez by Richard Yates “Take Five. There's a certain piece that if we don’t play, we’re in trouble.” —Dave Brubek It was a familiar situation: deep in the stacks, surrounded by ancient scores, browsing for music that might find artful expression through the guitar. Perusing pages of choral music, I was suddenly struck by the realization that what I was doing was precisely what lutenists 400 years ago had done. While not exactly déjà vu, there was a strong sense of threading my way along paths first explored centuries ago. And if I was struggling with this source material, did they also? What solutions did they find and what tricks did they devise? What can we learn from them to help solve the puzzle of intabulating Renaissance vocal polyphony? The 16th century saw the gradual evolution of musical ideals that culminated in the works of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525–94). Polyphonic music was to be a smooth, effortless flow of independent voices. Predominant stepwise movement emphasized continuity of individual lines but without drawing undue attention to any particular one. Dissonance was largely confined to the weak beats and passing tones or softened through suspensions. With its unique capacity for continuous modulation of timbre, pitch and volume, the human voice was exquisitely suited to this style. The articulation of syllables, true legato and subtle, unobtrusive portamento that connects phonemes and that is inherent in singing all facilitated the tracking of voices through a closely woven texture. Renaissance choral music is inextricably bound up with, and dependent on, the qualities of human voice. -

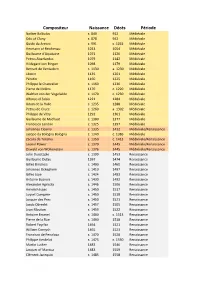

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus C

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus c. 840 912 Médiévale Odo of Cluny c. 878 942 Médiévale Guido da Arezzo c. 991 c. 1033 Médiévale Hermann of Reichenau 1013 1054 Médiévale Guillaume d'Aquitaine 1071 1126 Médiévale Petrus Abaelardus 1079 1142 Médiévale Hildegard von Bingen 1098 1179 Médiévale Bernart de Ventadorn c. 1130 a. 1230 Médiévale Léonin 1135 1201 Médiévale Pérotin 1160 1225 Médiévale Philippe le Chancelier c. 1160 1236 Médiévale Pierre de Molins 1170 c. 1220 Médiévale Walther von der Vogelwide c. 1170 c. 1230 Médiévale Alfonso el Sabio 1221 1284 Médiévale Adam de la Halle c. 1235 1288 Médiévale Petrus de Cruce c. 1260 a. 1302 Médiévale Philippe de Vitry 1291 1361 Médiévale Guillaume de Machaut c. 1300 1377 Médiévale Francesco Landini c. 1325 1397 Médiévale Johannes Ciconia c. 1335 1412 Médiévale/Renaissance Jacopo da Bologna Bologna c. 1340 c. 1386 Médiévale Zacara da Teramo c. 1350 c. 1413 Médiévale/Renaissance Leonel Power c. 1370 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance Oswald von Wolkenstein c. 1376 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance John Dunstaple c. 1390 1453 Renaissance Guillaume Dufay 1397 1474 Renaissance Gilles Binchois c. 1400 1460 Renaissance Johannes Ockeghem c. 1410 1497 Renaissance Gilles Joye c. 1424 1483 Renaissance Antoine Busnois c. 1430 1492 Renaissance Alexander Agricola c. 1446 1506 Renaissance Heinrich Isaac c. 1450 1517 Renaissance Loyset Compère c. 1450 1518 Renaissance Josquin des Prez c. 1450 1521 Renaissance Jacob Obrecht c. 1457 1505 Renaissance Jean Mouton c. 1459 1522 Renaissance Antoine Brumel c. 1460 c. 1513 Renaissance Pierre de la Rue c. 1460 1518 Renaissance Robert Fayrfax 1464 1521 Renaissance William Cornysh 1465 1523 Renaissance Francisco de Penalosa c. -

An Interview with Shirley Robbins

september 2008 Published by the American Recorder Society, Vol. XLIX, No. 4 3IMPLYHEAVENLYn OURNEWTENORSANDBASSESWITH BENTNECK 0LEASEASKFOROURNEW FREECATALOGUEANDTHE RECORDERPOSTER Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Attaignant: Second Livre de Danceries Gervaise: Quart Livre de Danceries, 1550 For SATB Recorders For SATB/ATTB Recorders Very little ensemble dance music has come down Whilemuchlikethetitleatleftinthatitcontainsahefty from the 16th century. The Attaignant dance prints 42 pieces, this volume 4 is distinguished by a number of collection is one of the only collections of ensemble particularly elegant pavanes based on chansons of the pe- pieces of that period. This volume 2 is probably the riod. most varied of the Attaingnant books, containing Item # LPMAD04, $13.25 basse dances, tourdions, branles, pavanes and galli- Also in this collection... ards. The tunes are mostly French in origin, though LPMAD05: 5th Livre de Dances, 53 pieces. $12.25 there are a few Italian pieces. Many are based on LPMAD06: 6th Livre de Dances, 48 pieces. $12.25 famous chansons of the time. 38 page score with extensive introduction LPMAD07: 7th Livre de Dances, 27 pieces. $8.75 and performance notes. Item # LPMAD02, $13.25 Praetorius: Dances from Terpsichore For SATB/SATTB Recorders 127(:257+<1(:6 From this major German contribu- tor to early baroque music came his from your friends at Magnamusic Distributors collection of 312 short French and Italian instrumental dances in Mendelssohn: Overture to ‘A Midsummer four, five and six parts, including courantes, voltes, Nights Dream’, Abridged, Charlton, arr. bransles, gaillardes, ballets, pavanes, canaries, and For NSSAATTB(Gb) recorders bourees. Volumes 1 to 4, Large bound scores, The famous piece that helped popularize the famous play. -

Christmas and Epiphany G E N E R a L E D I T O R Robert B

Christmas and Epiphany G E N E R A L E D I T O R Robert B. Kruschwitz A rt E di TOR Heidi J. Hornik R E V ie W E D I T O R Norman Wirzba PROCLAMATION EDITOR William D. Shiell A S S I S tant E ditor Heather Hughes PRODUCTION ASSISTANT Elizabeth Sands Wise D E S igner Eric Yarbrough P UB li SH E R The Center for Christian Ethics Baylor University One Bear Place #97361 Waco, TX 76798-7361 P H one (254) 710-3774 T oll -F ree ( US A ) (866) 298-2325 We B S ite www.ChristianEthics.ws E - M ail [email protected] All Scripture is used by permission, all rights reserved, and unless otherwise indicated is from New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. ISSN 1535-8585 Christian Reflection is the ideal resource for discipleship training in the church. Multiple copies are obtainable for group study at $3.00 per copy. Worship aids and lesson materials that enrich personal or group study are available free on the Web site. Christian Reflection is published quarterly by The Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University. Contributors express their considered opinions in a responsible manner. The views expressed are not official views of The Center for Christian Ethics or of Baylor University. The Center expresses its thanks to individuals, churches, and organizations, including the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, who provided financial support for this publication. -

Scarica Programma

CON L’ADESIONE DEL PRESIDENTE DELLA REPUBBLICA CON IL CONTRIBUTO DELLA DIREZIONE GENERALE DELLO SPETTACOLO DAL VIVO MINISTERO PER I BENI E LE ATTIVITA' CULTURALI E DEL TURISMO FESTINA LENTE GEMMA BERTAGNOLLI ROMAFESTIVALBAROCCO LA MAGNIFICA COMUNITA’ I MUSICALI AFFETTI VII EDIZIONE 21 NOVEMBRE – 27 DICEMBRE 2014 IL SOGNO BAROCCO CAPPELLA GIULIA LA TEMPESTA ALESSANDRO ALBENGA ODECATHON LA CONTRACLAU FRANCESCO DI LERNIA CAPPELLA MARIANA CAPPELLA GIULIA Tel. +39 06.92958872 Cell. +39 335.5700072 www.romafestivalbarocco.it BaRocco ROMA FESTIVAL BAROCCO VII EDIZIONE 2014 21 NOVEMBRE – 27 DICEMBRE Festival Roma Roma La VII Edizione, in programma dal 21 novembre al PROGRAMMA 27 dicembre 2014, presenterà un ciclo di tredici concerti con esecuzioni legate alla tradizione Venerdì 21 novembre ore 19.30 Venerdì 5 dicembre ore 21.00 musicale romana dei secoli XVI, XVII e XVIII. CHIESA DI S. MARIA IN MONSERRATO SANTA MARIA IN VALLICELLA Accanto agli appuntamenti dedicati alla Polifonia ENSEMBLE “FESTINA LENTE” “LA RELIGIOSITA’” - “LA TRADIZIONE” del cinque-seicento (i concerti di Festina Lente, TOMAS LUIS DE VICTORIA: Coro della Venerabile Cappella Giulia della Basilica Cappella Giulia, La Tempesta, Odhecaton, Cappella OFFICIUM DEFUNCTORUM (1605) di San Pietro in Vaticano Mariana), figurano quelli dedicati alla Cantata Michele Gasbarro Direttore Padre Pierre Paul OMV direttore barocca (Sogno Barocco), all’arte tastieristica (F. Di G. Animuccia: Missa 'Ave Maris Stella' a 4 voci Lernia e A. Albenga) e all’Oratorio (Musicali Martedì 25 novembre ore 19.00 (PRIMA ESECUZIONE IN TEMPI MODERNI) Affetti). Nel calendario generale dei concerti la LICEO GINNASIO STATALE TERENZIO MAMIANI serata dedicata alla musica medievale (Contraclau) ALCHIMIE BAROCCHE...”INCONTRARSI IN CONCERTO” Sabato 6 dicembre ore 21.00 rappresenta una voluta “digressione”; quella Gemma Bertagnolli Canto BASILICA DI SAN LORENZO IN LUCINA dedicata alle musiche di L. -

The Choir of King's College London

The Choir of King’s College London Gareth Wilson The Choir of King’s College London Gareth Wilson IN MEMORIAM Alexander May, Graham Thorpe organ 1 William Byrd (1539/40–1623) Laudibus in sanctis [5:18] 9 Robert Busiakiewicz (b. 1990) Ego sum resurrectio et vita [2:27] 2 Matthew Kaner (b. 1986) Duo seraphim [5:09] Rob Keeley (b. 1960) Magnificat & Nunc dimittis Eleanor Williams, Mimi Doulton, Elizabeth Gornall, Eleanor Wood sopranos 10 Magnificat [4:15] Ben Taylor-Davies, Billie Hylton, Caitlin Goreing, Jacob Werrin, Rosanna Goodall altos 11 Nunc dimittis [2:52] James Rhoads, Miles Ashdown tenors Alexander May organ Freddie Benedict, Alex Pratley basses Antony Pitts (b. 1969) Pie Jesu (Prayer of the Heart) Gareth Wilson (b. 1976) Magnificat & Nunc dimittis (Collegium Regale) 12 I [6:55] 3 Magnificat [5:33] 13 II [5:38] 4 Nunc dimittis [5:27] Ciara Power, Lindsey James sopranos Graham Thorpe organ Caitlin Goreing, David Lee altos Silvina Milstein (b. 1956) ushnarasmou – untimely spring James Rhoads tenor Scott Richardson, Joey Edwards basses 5 ushnarasmou [4:01] 6 kusumaani [4:41] 14 Matthew Martin (b. 1976) An Invocation to the Holy Spirit [2:43] Eleanor Williams, Mimi Doulton solo sopranos Lindsey James, Charlotte Nohavicka ripieno sopranos 15 Giovanni Pierluigi Quam pulchri sunt gressus tui [4:38] Matthew O’Keeffe, Rosanna Goodall solo altos da Palestrina (1525–1594) Billie Hylton, Jacob Werrin ripieno altos Robyn Donnelly soprano Miles Ashdown, James Green solo tenors Jaivin Raj ripieno tenor 16 Jacob Clemens non Papa (c.1510–1555/6) Ego flos campi [5:27] Joey Edwards, Alex Pratley, Dominic Veall ripieno basses 17 Francis Grier (b. -

Cité De La Musique

CITÉ DE LA MUSIQUE DIMANCHE 11 MARS 2012 DE 14H30 À 17H30 CONCERT-PROMENADE AU MUSÉE Concerts, ateliers musicaux pour les jeunes à partir de 6 ans et une parade finale avec tous les artistes CONCERT-PROMENADE | DIMANCHE 11 MARS | CARNAVAL AU MUSÉE CONCERT-PROMENADE CARNAVAL AU MUSÉE ESPACE XVIIE SIÈCLE Ce concert-promenade de février est dédié au carnaval, un carnaval pour rire, chanter et 14h30 et 15h30 – Flandre danser grâce aux coutumes de la Renaissance en Flandre, moldaves et cajuns de Louisiane. Le parcours ludique et festif se terminera dans le Musée par une parade. Le Combat de Carnaval et de Carême. Musiques de carnaval en Flandre à la Renaissance Un atelier Charivari est organisé pour les enfants à partir de 6 ans (de 16H à 17h30). Inscription À travers un parcours original, l’ensemble Non Papa vous invite à suivre pas à pas les détails à partir de 13h à l’accueil de la rue musicale. d’un tableau bruyant de Pieter Brueghel dit l’Ancien (1525-1569), Le combat de Carnaval et de Carême (1559). « En entrant dans ce tableau, imaginons que nous nous arrêtons au coin d’une rue, en plein Mardi Gras, dernier jour consacré à Carnaval... » MUSÉE Jacob Obrecht (1457-1505) Rumpfeltier – éd. Petrucci 1501 Musée Espace Espace Espace Salle XVIIe siècle XVIIIe siècle XIXe siècle Jean Servin (1530-1595) pédagogique Fricassée des cris de Paris – éd. Pesnot 1578 de 14h30 à 15h Flandre Nicolle des Celliers d’Hesdin (début XVIe siècle-1538) Ramonnez-moy ma cheminée – éd. Attaingnant 1546 de 15h à 15h30 Moldavie Jean Braconnier (mort avant 1512) Amour me trocte par la panse – éd. -

Bridging the Centuries 2 Songs from Shakespeare’S Plays, Then and Now Love Songs of Petrarch and the Song of Songs

Early Music Hawaii presents Bridging the Centuries 2 Songs from Shakespeare’s Plays, Then and Now Love Songs of Petrarch and the Song of Songs The Early Music Hawaii Chamber Singers Georgine Stark and Naomi Castro soprano Karyn Castro and Diane Koshi alto Karol Nowicki and Randy Reynolds tenor Jeremy Wong and Keane Ishii bass Katherine Crosier keyboard Jeremy Wong conductor Saturday, April 2, 2016, 7:30 pm Lutheran Church of Honolulu 1730 Punahou Street Saturday, April 9, 2016, 5:00 pm Lutheran Church of the Holy Trinity 77-165 Lako Street, Kailua-Kona This program is supported in part by the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts through appropriations from the Legislature of the State of Hawaii and by the National Foundation for the Arts Program Please hold applause until the pause between each “set” 1. Poems by Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch ) and Ruffo I Vidi in Terra Baldassare Donato (1529-1603) Franz Liszt (1811-1896) Io Piango (Petrarch) Luca Marenzio (1553-1599) (Ruffo) Morten Lauridsen (b.1943) 2. From the Song of Songs Nigra Sum Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) Pablo Casals (1876-1973) Ego Flos Campi Jacob Clemens non Papa (1510-1556) I am the Rose of Sharon William Billings (1746-1800) Intermission 3. A Midsummer Night’s Dream (and other plays) Ah Robin, Gentle Robin William Cornysh (1468-1523) Over Hill, Over Dale Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) 4. Two Gentlemen of Verona Who is Silvia? Anon (16th century) George Shearing (1919-2011) 5. Twelfth Night & Measure for Measure O Mistress Mine Thomas Morley (1558-1602) Matt Harris (b. -

PIOTR KRASNY Cultural and National Identity in 18Th-Century Lwow: Three

Originalveröffentlichung in: Kwilecka, Anna u.a. (Hrsg.): Art and national identity in Poland and England, London 1996, S. 41-50 PIOTR KRASNY Cultural and national identity in 18th-century Lwow: three nations - three religions - one art In many ethnically heterogeneous regions of Europe (in the Netherlands, for instance; in Northern Ireland and in the Balkans) national identity was and still is tantamount to religious identity. This has produced specific effects in religious art in these regions. Differences resulting from religious traditions have been doubled by differences in distinct national art traditions. On the other hand, the traditions would often blend, especially after years of coexistence, leading to a certain unification of religious art forms. An interesting example of this process can be seen in the art of Lwow and its region in the 18th century. National and religious identity in Lwow and its region In the Middle Ages Lwow was one of the most important towns in the small Ruthenian D"chy with Halicz as its capital. In the 13th century and at the beginning of the 14th century the duchy was ravaged by Tatars which resulted in its depopulation. When the '°cal dynasty died out in the 1340s, the Polish king Casimir the Great annexed the duchy. new ruler decided to establish Polish settlements and brought in settlers mainly from central Poland. They found their homes mostly in towns, though sometimes they would Set up new villages. Casimir the Great turned the duchy into the Ruthenian province of toe Polish Kingdom and moved its capital to Lwow. Besides being the seat of the Orthodox bishop it soon became also the seat of the Roman Catholic archbishop. -

BCA Schedule

S Legal profession S37WR S Law Law S Legal profession S34 S2 . Primary materials Study in law S34 G * This class is used only under particular jurisdictions; . Student bar associations S34 GGD e.g. English law - Primary materials - Statutes SN2 G. S34 GGM . Moots * See Auxiliary Schedule S2 for instructions. GTC . Law schools (general) H Research in law * For research in the narrow sense of searching the legal . Common subdivisions literature, see S3R D. * These conform to the order of classes 2/9 in Auxiliary * See also Jurisprudence S5A Schedule 1 but with substantial modifications of * Add to S34 H numbers 3/9 following K in K3/K9. notation. H6 . Methodology * Add to S3 numbers 2/3 in Auxiliary Schedule 1 with the additions shown at S33 Y. H6M . Models S3 . General works on the law J Lawyers, attorneys, advocates, practitioners * For works on the formal status, etc. of particular parties S33 B . Dictionaries, encyclopedias or persons in the legal profession. For works on their G . Journals, periodicals, serials practical functioning, see Practice of law S6A. * For indexing & abstracting journals, see S3WH. * Theoretically, BC2 subordinates personnel to their H . Yearbooks specific function (e.g. advocacy). But the varied nature J . Directories, law lists of the tasks undertaken & the possibilities of * Primarily for use in qualifying persons, reorganization which may alter the degree of organizations, etc. specialization of particular personnel make this hard & LR . Conference proceedings fast distinction impracticable. Most of the literature RA . Literature & the law refers to types of personnel, but this should be * Imaginative literature, etc. interpreted as covering their duties as well as their office. -

Antonio De Cabeçon (Castrillo Mota De Judíos 1510 – Madrid 1566)

Antonio de Cabeçon (Castrillo Mota de Judíos 1510 – Madrid 1566) Comiençan las canciones glosadas y motetes a quatro Fol. 69 – 104 from : Obras de Musica para Tecla, Arpa y Vihuela Madrid 1578 15 pieces in 4 voices and 3 pieces in 3 voices transcribed for keyboard instrument and harp and arranged for recorders or other instruments by Arnold den Teuling Keyboard instrument or harp 2016 Introduction to the edition of the remaining part of Antonio de Cabezón’s Obras de Musica para Tecla, Arpa y Vihuela, Madrid 1578 Hernando de Cabeçon (Madrid 1541-Valladolid 1602), as he spelled his name, published his father’s works in 1578, despite the year 1570 on the title page. The royal privilege for publication bears the date 1578 on the page which also contains the “erratas”. The Obras contain an extensive and very useful introduction in unnumbered pages, followed by 200 folio’s of printed music, superscribed in the upper margin “Compendio de Musica / de Antonio de Cabeçon.” A facsimile is in IMSLP. The first editor Felipe Pedrell (1841-1922), Hispaniae Schola Musica Sacra, Vols.3, 4, 7, 8, Barcelona: Juan Pujol & C., 1895-98, did not provide a complete edition, but a little more than half of it. He also gives an extensive introduction in Spanish and French. This edition may be found in IMSLP too. Pedrell stopped his complete edition after folio 68 (of 200), and made a selection of remaining works. He mostly passed over the intabulations of works of other composers, apparently objecting a lack of originality to them. Later editors mostly contented themselves with reprinting parts of Pedrell‘s work, possibly with corrections, and optical adaptation to modern use.