ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR (ABG 503) LECTURE NOTES Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operant Conditioning

Links to Learning Objectives DEFINITION OF LEARNING OPERANT CONDITIONING (Part 2) LO 5.1 Learning LO 5.8 Controlling behavior and resistance LO 5.9 Behavior modification CLASSICAL CONDITIONING LO 5.2 Study of and important elements COGNITIVE LEARNING LO 5.3 Conditioned emotional response LO 5.10 Latent learning, helplessness and insight OPERANT CONDITIONING (Part 1) LO 5.4 Operant, Skinner and Thorndike OBSERVATIONAL LEARNING LO 5.5 Important concepts LO 5.11 Observational learning theory LO 5.6 Punishment problems LO 5.7 Reinforcement schedules Learning Classical Emotions Operant Reinforce Punish Schedules Control Modify Cognitive Helpless Insight Observe Elements Operant Conditioning Operant Stimuli Behavior 5.8 How do operant stimuli control behavior? • Discriminative stimulus –cue to specific response for reinforcement Learning Classical Emotions Operant Reinforce Punish Schedules Control Modify Cognitive Helpless Insight Observe Elements 1 Biological Constraints • Instinctive drift – animal’s conditioned behavior reverts to genetic patterns – e.g., raccoon washing, pig rooting Learning Classical Emotions Operant Reinforce Punish Schedules Control Modify Cognitive Helpless Insight Observe Elements ehavior modification Application of operant conditioning to effect change Behavior Modification 5.9 What is behavior modification? • Use of operant techniques to change behavior Tokens Time out Applied Behavior Analysis Learning Classical Emotions Operant Reinforce Punish Schedules Control Modify Cognitive Helpless Insight Observe Elements -

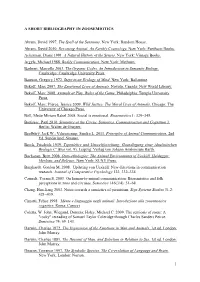

1 a SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY in ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David

A SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY IN ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Random House. Abram, David 2010. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York: Pantheon Books. Ackerman, Diane 1991. A Natural History of the Senses. New York: Vintage Books. Argyle, Michael 1988. Bodily Communication. New York: Methuen. Barbieri, Marcello 2003. The Organic Codes. An Introduction to Semantic Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bateson, Gregory 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantine. Bekoff, Marc 2007. The Emotional Lives of Animals. Novato, Canada: New World Library. Bekoff, Marc 2008. Animals at Play. Rules of the Game. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Bekoff, Marc; Pierce, Jessica 2009. Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Böll, Mette Miriam Rakel 2008. Social is emotional. Biosemiotics 1: 329–345. Bouissac, Paul 2010. Semiotics at the Circus. Semiotics, Communication and Cognition 3. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Bradbury, Jack W.; Vehrencamp, Sandra L. 2011. Principles of Animal Communication, 2nd Ed. Sunderland: Sinauer. Brock, Friedrich 1939. Typenlehre und Umweltforschung: Grundlegung einer idealistischen Biologie (= Bios vol. 9). Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosium Barth. Buchanan, Brett 2008. Onto-ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau, and Deleuze. New York: SUNY Press. Burghardt, Gordon M. 2008. Updating von Uexküll: New directions in communication research. Journal of Comparative Psychology 122, 332–334. Carmeli, Yoram S. 2003. On human-to-animal communication: Biosemiotics and folk perceptions in zoos and circuses. Semiotica 146(3/4): 51–68. Chang, Han-liang 2003. Notes towards a semiotics of parasitism. Sign Systems Studies 31.2: 421–439. -

Observation of Behavior, Inference of Function, and the Study of Learning

Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 1994, 1 (1), 73-88 Observation of behavior, inference of function, and the study of learning WILLIAM TIMBERLAKE and FRANCISCO J. SILVA Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana Before the present century, the primary means of studying animals was observation of the form and effects of their behavior combined with presumption of their intent. In the present century, ethologists continued to emphasize observation of form and replaced presumption of intent with the study of proximate function and evolution. In contrast, most learning psychologists mini mized both observation of form and presumption of intent by defining behavior in terms of sim ple environmental effects and establishing intent by deprivation operations, We discuss advan tages of the use of observation in the study of learning, examine arguments that it is unnecessary, irrelevant, and unscientific, and consider some practical considerations in using observation. We conclude that observation of the form of behavior and concern with its ecological function should be an important part of the arsenal of techniques used to study learning. Observation has been the dominant method of study imals (Warden, 1927), anthropomorphically viewing the ing the behavior of animals since the beginning of re latter as partially disguised people enmeshed in a web of corded history (Warden, 1927). Observation provided the human goals, social relations, and rules (Aesop, approx underpinnings of the writings of systematists such as imately 620 B.C.; Selous, 1908). Other observers adhered Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) and Darwin (1859), story tellers to a more animal-centered description and inference of such as Seton (1913) and Kipling (1894), collectors of function (Craig, 1918; Huxley, 1914). -

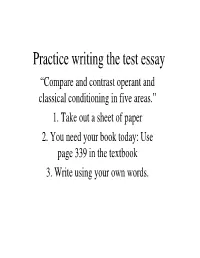

Operant Conditioning and Pigs

Practice writing the test essay “Compare and contrast operant and classical conditioning in five areas.” 1. Take out a sheet of paper 2. You need your book today: Use page 339 in the textbook 3. Write using your own words. Exchange papers • Peer edit their paper. • Check to see if they have the needed terms and concepts. • If they don’t add them. • If they do give them a plus sign (+) • Answers in red Essay note • You won’t be able to use your notes or book on Monday’s test. .∑¨π®µªΩ∫ "≥®∫∫∞™®≥"∂µ´∞ª∞∂µ∞µÆ Remembering the five categories • B • R • A • C • E B • Biological predispositions "≥®∫∫∞™®≥ ™∂µ´∞ª∞∂µ∞µÆ©∞∂≥∂Æ∞™®≥ /π¨´∞∫∑∂∫∞ª∞∂µ∫ ≥¨®πµ∞µÆ∞∫™∂µ∫ªπ®∞µ¨´©¿®µ®µ∞¥ ®≥∫©∞∂≥∂Æ¿ µ®ªºπ®≥∑π¨´∞∫∑∂∫∞ª∞∂µ∫™∂µ∫ªπ®∞µ∫∂π≥∞¥ ∞ª∫ æ Ø®ª∫ª∞¥ º≥∞®µ´π¨∫∑∂µ∫¨∫™®µ©¨®∫∫∂™∞®ª¨´ ©¿ªØ¨®µ∞¥ ®≥ John Garcia’s research, 322 • Biological predispositions • John Garcia: animals can learn to avoid a drink that will make them sick, but not when its announced by a noise or a light; !≥∂Æ∞™®≥/π¨´∞∫∑∂∫∞ª∞∂µ∫ C o u r t e s & ®π™∞®∫Ø∂æ ¨´ªØ®ªª ¨´ºπ®ª∞∂µ y o f J o ©¨ªæ ¨¨µª ¨"2®µ´ªØ¨4 2¥ ®¿©¨ h n G a r ≥∂µÆ&Ø∂ºπ∫'©ºª¿¨ªπ¨∫º≥ª∞µ c i a ™∂µ´∞ª∞∂µ∞µÆ ©∞∂≥∂Æ∞™®≥≥¿®´®∑ª∞Ω¨ )∂ص& ®π™∞® "2&ª®∫ª¨'≥¨´ª∂™∂µ´∞ª∞∂µ∞µÆ®µ´µ∂ª ª∂∂ªØ¨π∫&≥∞Æت∂π∫∂ºµ´' Human example • We more easily are classically conditioned to fear snakes or spiders, rather than flowers. -

Edward C. Tolman (1886-1959)

Edward C. Tolman (1886-1959) Chapter 12 1 Edward C. Tolman 1. Born (1886) in West Newton, Massachusetts. 2. B.S from MIT. PhD from Harvard. 3. Studied under Koffka. 4. 1915-1918 taught at www.uned.es Northwestern University. Released from university. Pacifism! (1886-1959) 2 Edward C. Tolman 5. Moved to University of California-Berkeley and remained till retirement. 6. Dismissed from his position for not signing the “loyalty oath”. Fought for academic freedom and www.uned.es reinstated. 7. Quaker background (1886-1959) therefore hated war. Rebel in life and psychology. 3 1 Edward C. Tolman 8. Did not believe in the unit of behavior pursued by Pavlov, Guthrie, Skinner and Hull. “Twitchism” vs. molar behavior. 9. Learning theory a blend of Gestalt psychology and www.uned.es behaviorism. 10. Died 19 Nov. 1959. (1886-1959) 4 Comparison of Schools Behaviorism Gestalt Gestalt psychologists Behaviorists believed believed in the in “elements” of S-R “whole” mind or associations. mental processes. Observation, Observation and Experimentation and Experimentation Introspection Approach: Behavioral Approach: Cognitive 5 Tolman’s idea about behavior 1. Conventional behaviorists do not explain phenomena like knowledge, thinking, planning, inference, intention and purpose in animals. In fact, they do not believe in mental phenomena like these. 2. Tolman on the other hand describes animal behavior in all of these terms and takes a “Gestalt” viewpoint on behavior, which is to look at behavior in molar or holistic terms. 6 2 Tolman’s idea about behavior 3. So rat running a maze, cat escaping the puzzle box and a man talking on the phone are all molar behaviors. -

The Behavioral Effects of Feeding Enrichment on a Zoo-Housed Herd of African Elephants (Loxodonta Africana)

Winthrop University Digital Commons @ Winthrop University Graduate Theses The Graduate School 8-2017 The Behavioral Effects of Feeding Enrichment on a Zoo-Housed Herd of African Elephants (Loxodonta africana) Caroline Marie Driscoll Winthrop University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses Part of the Biology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Driscoll, Caroline Marie, "The Behavioral Effects of Feeding Enrichment on a Zoo-Housed Herd of African Elephants (Loxodonta africana)" (2017). Graduate Theses. 71. https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses/71 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BEHAVIORAL EFFECTS OF FEEDING ENRICHMENT ON A ZOO- HOUSED HERD OF AFRICAN ELEPHANTS (LOXODONTA AFRICANA) A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the Department of Biology Winthrop University July, 2017 By Caroline Marie Driscoll ii ABSTRACT A comprehensive study on the behavioral effects of feeding enrichment was conducted on six African elephants housed at the North Carolina Zoological Park in Asheboro, NC. The herd is comprised of are two adult males, three adult females, and one subadult female. The study was conducted over a 10-month period and consisted of focal sample observations across three conditions. Observations were recorded during the baseline condition (June to September) and continued through the introduction of feeding enrichment. -

Adaptability of Innate Motor Patterns and Motor Control Mechanisms

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (1986) 9, 585-638 Printed in the United States of America Adaptability of innate motor patterns and motor control mechanisms M. B. Berkinblit," A. G. Feldman," and O. I. Fukson" "Institute of Information Transmission Problems, Academy of Sciences, Moscow 101447, U.S.S.R. and "Moscow State University, Moscow 117234, U.S.S.R. Abstract: The following factors underlying behavioral plasticity are discussed: (1) reflex adaptability and its role in the voluntary control of movement, (2) degrees of freedom and motor equivalence, and (3) the problem of the discrete organization of motor behavior. Our discussion concerns a variety of innate motor patterns, with emphasis on the wiping reflex in the frog. It is proposed that central regulation of stretch reflex thresholds governs voluntary control over muscle force and length. This suggestion is an integral part of the equilibrium-point hypothesis, two versions of which are compared. Kinematic analysis of the wiping reflex in the spinal frog has shown that each stimulated skin site is associated with a group of different but equally effective trajectories directed to the target site. Such phenomena reflect the principle of motor equivalence - the capacity of t h e neuronal structures responsible for movement to select one or another of a set of p o s s i b l e trajectories leading to the goal. Redundancy of degrees of freedom at the neuronal level as well as at the mechanical level of the body's joints makes motor equivalence possible. This sort of equivalence accommodates the overall flexibility of motor behavior. -

Animal Conflict "1,

ANIMAL CONFLICT "1, ...... '", .. r.", . r ",~ Illustrated by Leslie M. Downie Department of Zoology, University of Glasgow ANIMAL CONFLICT Felicity A. Huntingford and Angela K. Turner Department of Zoology, University of Glasgow .-~ ' ..... '. .->, I , f . ~ :"fI London New York CHAPMAN AND HALL Chapman and Hall Animal Behaviour Series SERIES EDITORS D.M. Broom Colleen Macleod Professor of Animal Welfare, University of Cambridge, UK P.W. Colgan Professor of Biology, Queen's University, Canada Detailed studies of behaviour are important in many areas of physiology, psychology, zoology and agriculture. Each volume in this series will provide a concise and readable account of a topic of fundamental importance and current interest in animal behaviour, at a level appropriate for senior under graduates and research workers. Many facets of the study ofanimal behaviour will be explored and the topics included will reflect the broad scope of the subject. The major areas to be covered will range from behavioural ecology and sociobiology to general behavioural mechanisms and physiological psychology. Each volume will provide a rigorous and balanced view of the subject although authors will be given the freedom to develop material in their own way. To Tim) Joan and Jessica) with thanks) and to all the children who provided inspiration First published in 1987 by Chapmatl and Hall Ltd 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Published in the USA by Chapman atld Hall 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 © 1987 Felicity A. Huntingford and Angela K. Turner Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1987 ISBN -13: 978-94-010-9008-7 This title is available in both hardbound and paperback editions. -

Naturalizing Anthropomorphism: Behavioral Prompts to Our Humanizing of Animals

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 2007 Naturalizing Anthropomorphism: Behavioral Prompts to Our Humanizing of Animals Alexandra C. Horowitz Barnard College Marc Bekoff University of Colorado Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/acwp_habr Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Comparative Psychology Commons, and the Other Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Horowitz, A. C., & Bekoff, M. (2007). Naturalizing anthropomorphism: Behavioral prompts to our humanizing of animals. Anthrozoös, 20(1), 23-35. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Naturalizing Anthropomorphism: Behavioral Prompts to Our Humanizing of Animals Alexandra C. Horowitz1 and Marc Bekoff2 1 Barnard College 2 University of Colorado – Boulder KEYWORDS anthropomorphism, attention, cognitive ethology, dogs, humanizing animals, social play ABSTRACT Anthropomorphism is the use of human characteristics to describe or explain nonhuman animals. In the present paper, we propose a model for a unified study of such anthropomorphizing. We bring together previously disparate accounts of why and how we anthropomorphize and suggest a means to analyze anthropomorphizing behavior itself. We introduce an analysis of bouts of dyadic play between humans and a heavily anthropomorphized animal, the domestic dog. Four distinct patterns of social interaction recur in successful dog–human play: directed responses by one player to the other, indications of intent, mutual behaviors, and contingent activity. These findings serve as a preliminary answer to the question, “What behaviors prompt anthropomorphisms?” An analysis of anthropomorphizing is potentially useful in establishing a scientific basis for this behavior, in explaining its endurance, in the design of “lifelike” robots, and in the analysis of human interaction. -

14 Learning, I: the Acquisition of Knowledge

14 LEARNING, I: THE ACQUISITION OF KNOWLEDGE Most animals are small and don’t live long; flies, fleas, protists, nematodes and similar small creatures comprise most of the fauna of the planet. A small animal with short life span has little reason to evolve much learning ability. Because it is small, it can have little of the complex neu- ral apparatus needed; because it is short-lived it has little time to exploit what it learns. Life is a tradeoff between spending time and energy learning new things, and exploiting things already known. The longer an animal’s life span, and the more varied its niche, the more worthwhile it is to spend time learning.1 It is no surprise; therefore, that learning plays a rather small part in the lives of most ani- mals. Learning is not central to the study of behavior, as was at one time believed. Learning is interesting for other reasons: it is involved in most behavior we would call intelligent, and it is central to the behavior of people. “Learning”, like “memory”, is a concept with no generally agreed meaning. Learning cannot be directly observed because it represents a change in an animal’s potential. We say that an animal has learned something when it behaves differently now because of some earlier ex- perience. Learning is also situation-specific: the animal behaves differently in some situations, but not in others. Hence, a conclusion about whether or not an animal has learned is valid only for the range of situations in which some test for learning has been applied. -

A Review of Some Aspects of Avian Field Ethology 1

A REVIEW OF SOME ASPECTS OF AVIAN FIELD ETHOLOGY 1 ROBERT W. FICKEN AND MILLICENT S. FICKEN T•E last 30 yearshave seen the developmentof a new approachto the study of behavior, which has increasinglyinterested ornithologists as they have attemptedto understandavian biologyfully. This new ap- proachis now known as ethology. Both amateur and professionalorni- thologistshave contributedto its progressfrom the beginning. A basictenet of ethologyis that all behaviorof animalscan eventually be understood.The ethologistattempts to explainbehavior functionally (what doesit do for the animal?), causally(what are the internal and externalfactors responsible for each given behavior?),and evolutionarily (what is the probablephylogeny of the behavior,how doesit contribute to th'esurvival of the species,and what are the selectivepressures acting uponit?) (seeTinbergen, 1951, 1959; Hinde, 1959b). Somebasic proceduresare essentialin an ethologicalstudy (Hinde, 1959b: 564). The first step is to describeand classifyall the behavior of an animal, at the same time, if possible,dividing the behavior into logicalunits which can be dealt with furtherin other disciplines--particu- larly physiologyand ecology(see Russellet al., 1954). Althoughstudies often beginqualitatively, they eventuallyshould be quantified. Generali- zations,which are to be valid for many species,must be basedon work using closelyrelated speciesfirst, and more distantly related ones later. The animal is studied as an integrated whole. Some workers, notably Konrad Lorenz, keep and breed animalsin captivity under closescrutiny. Most of this paper dealswith communicationof birds. We have stressed particularly the analysisof displays,their evolution,and their relation to taxonomy--topicsof great interest to systematicornithologists as well as to ethologists.In addition, we discusscertain maintenanceactivities. LITERATURE OF ET•OLOC¾ Much of the early ethologicalliterature appearedin Europeanpublications, but it is now also appearingin this country frequently. -

Hutnan Ethology Bulletin

Hutnan Ethology Bulletin VOLUME 12, ISSUE 1 ISSN 0739-2036 MARCH 1997 © 1997 The International Society for Human Ethology obviously not in the interests of the slaves. Why don't they go on strike? Because the slaves are not genetically related to anything that comes out of the nest where they are now working. Any gene that tended to make them go on strike would have no possibility of being benefited by the striking action. The copies of their genes, the ·copies of these striking workers genes, would be back in the home nest, and they would be being turned out by the queen, which the striking workers left behind. So there would be no opportunity for a phenotypic effect, namely striking, to benefit germ line copies of themselves. You also write about an ant species called Monomorium santschii in which there are no workers. The queen invades a nest of another species, and then uses chemicals to induce the An Interview of workers to adopt her, and to kill their own queen. How is it possible that natural sdection Richard Dawkins did not act against such incredible deception and manipulation, which must have been going By Frans Roes, Lauriergracht 127-II, 1016 on for millions of years? RK Amsterdam, The Netherlands In any kind of arms race, it is possible for one Richard Dawkins is a zoologist and Professor of . side in the arms race to lose consistently. Public. Understanding of Science at Oxford Monomorium santschii is a very rare species. If University. Of his best-selling books, The you look back in the ancestry of the victim- Selfish Gene (1976) probably did most in species over many millions of years, many of bringing the evolutionary message home to both their ancestors may never have encountered a professional and a general readership.