Social Dominance: a Behavioral Mechanism for Resource Allocation in Crayfish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meadow Pond Final Report 1-28-10

Comparison of Restoration Techniques to Reduce Dominance of Phragmites australis at Meadow Pond, Hampton New Hampshire FINAL REPORT January 28, 2010 David M. Burdick1,2 Christopher R. Peter1 Gregg E. Moore1,3 Geoff Wilson4 1 - Jackson Estuarine Laboratory, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH 03824 2 – Natural Resources and the Environment, UNH 3 – Department of Biological Sciences, UNH 4 – Northeast Wetland Restoration, Berwick ME 03901 Submitted to: New Hampshire Coastal Program New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services 50 International Drive Pease Tradeport Portsmouth, NH 03801 UNH Burdick et al. 2010 Executive Summary The northern portion of Meadow Pond Marsh remained choked with an invasive exotic variety of Phragmites australis (common reed) in 2002, despite tidal restoration in 1995. Our project goal was to implement several construction techniques to reduce the dominance of Phragmites and then examine the ecological responses of the system (as a whole as well as each experimental treatment) to inform future restoration actions at Meadow Pond. The construction treatments were: creeks, creeks and pools, sediment excavation with a large pool including native marsh plantings. Creek construction increased tides at all treatments so that more tides flooded the marsh and the highest spring tides increased to 30 cm. Soil salinity increased at all treatment areas following restoration, but also increased at control areas, so greater soil salinity could not be attributed to the treatments. Decreases in Phragmites cover were not statistically significant, but treatment areas did show significant increases in native vegetation following restoration. Fish habitat was also increased by creek and pool construction and excavation, so that pool fish density increased from 1 to 40 m-2. -

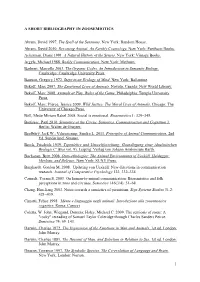

1 a SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY in ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David

A SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY IN ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Random House. Abram, David 2010. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York: Pantheon Books. Ackerman, Diane 1991. A Natural History of the Senses. New York: Vintage Books. Argyle, Michael 1988. Bodily Communication. New York: Methuen. Barbieri, Marcello 2003. The Organic Codes. An Introduction to Semantic Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bateson, Gregory 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantine. Bekoff, Marc 2007. The Emotional Lives of Animals. Novato, Canada: New World Library. Bekoff, Marc 2008. Animals at Play. Rules of the Game. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Bekoff, Marc; Pierce, Jessica 2009. Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Böll, Mette Miriam Rakel 2008. Social is emotional. Biosemiotics 1: 329–345. Bouissac, Paul 2010. Semiotics at the Circus. Semiotics, Communication and Cognition 3. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Bradbury, Jack W.; Vehrencamp, Sandra L. 2011. Principles of Animal Communication, 2nd Ed. Sunderland: Sinauer. Brock, Friedrich 1939. Typenlehre und Umweltforschung: Grundlegung einer idealistischen Biologie (= Bios vol. 9). Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosium Barth. Buchanan, Brett 2008. Onto-ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau, and Deleuze. New York: SUNY Press. Burghardt, Gordon M. 2008. Updating von Uexküll: New directions in communication research. Journal of Comparative Psychology 122, 332–334. Carmeli, Yoram S. 2003. On human-to-animal communication: Biosemiotics and folk perceptions in zoos and circuses. Semiotica 146(3/4): 51–68. Chang, Han-liang 2003. Notes towards a semiotics of parasitism. Sign Systems Studies 31.2: 421–439. -

The Evolution and Genomic Basis of Beetle Diversity

The evolution and genomic basis of beetle diversity Duane D. McKennaa,b,1,2, Seunggwan Shina,b,2, Dirk Ahrensc, Michael Balked, Cristian Beza-Bezaa,b, Dave J. Clarkea,b, Alexander Donathe, Hermes E. Escalonae,f,g, Frank Friedrichh, Harald Letschi, Shanlin Liuj, David Maddisonk, Christoph Mayere, Bernhard Misofe, Peyton J. Murina, Oliver Niehuisg, Ralph S. Petersc, Lars Podsiadlowskie, l m l,n o f l Hans Pohl , Erin D. Scully , Evgeny V. Yan , Xin Zhou , Adam Slipinski , and Rolf G. Beutel aDepartment of Biological Sciences, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN 38152; bCenter for Biodiversity Research, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN 38152; cCenter for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Arthropoda Department, Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, 53113 Bonn, Germany; dBavarian State Collection of Zoology, Bavarian Natural History Collections, 81247 Munich, Germany; eCenter for Molecular Biodiversity Research, Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, 53113 Bonn, Germany; fAustralian National Insect Collection, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia; gDepartment of Evolutionary Biology and Ecology, Institute for Biology I (Zoology), University of Freiburg, 79104 Freiburg, Germany; hInstitute of Zoology, University of Hamburg, D-20146 Hamburg, Germany; iDepartment of Botany and Biodiversity Research, University of Wien, Wien 1030, Austria; jChina National GeneBank, BGI-Shenzhen, 518083 Guangdong, People’s Republic of China; kDepartment of Integrative Biology, Oregon State -

Biodiversity and Trophic Ecology of Hydrothermal Vent Fauna Associated with Tubeworm Assemblages on the Juan De Fuca Ridge

Biogeosciences, 15, 2629–2647, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-2629-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Biodiversity and trophic ecology of hydrothermal vent fauna associated with tubeworm assemblages on the Juan de Fuca Ridge Yann Lelièvre1,2, Jozée Sarrazin1, Julien Marticorena1, Gauthier Schaal3, Thomas Day1, Pierre Legendre2, Stéphane Hourdez4,5, and Marjolaine Matabos1 1Ifremer, Centre de Bretagne, REM/EEP, Laboratoire Environnement Profond, 29280 Plouzané, France 2Département de sciences biologiques, Université de Montréal, C.P. 6128, succursale Centre-ville, Montréal, Québec, H3C 3J7, Canada 3Laboratoire des Sciences de l’Environnement Marin (LEMAR), UMR 6539 9 CNRS/UBO/IRD/Ifremer, BP 70, 29280, Plouzané, France 4Sorbonne Université, UMR7144, Station Biologique de Roscoff, 29680 Roscoff, France 5CNRS, UMR7144, Station Biologique de Roscoff, 29680 Roscoff, France Correspondence: Yann Lelièvre ([email protected]) Received: 3 October 2017 – Discussion started: 12 October 2017 Revised: 29 March 2018 – Accepted: 7 April 2018 – Published: 4 May 2018 Abstract. Hydrothermal vent sites along the Juan de Fuca community structuring. Vent food webs did not appear to be Ridge in the north-east Pacific host dense populations of organised through predator–prey relationships. For example, Ridgeia piscesae tubeworms that promote habitat hetero- although trophic structure complexity increased with ecolog- geneity and local diversity. A detailed description of the ical successional stages, showing a higher number of preda- biodiversity and community structure is needed to help un- tors in the last stages, the food web structure itself did not derstand the ecological processes that underlie the distribu- change across assemblages. -

Vertical and Horizontal Trophic Networks in the Aroid-Infesting Insect Community of Los Tuxtlas Biosphere Reserve, Mexico

insects Article Vertical and Horizontal Trophic Networks in the Aroid-Infesting Insect Community of Los Tuxtlas Biosphere Reserve, Mexico Guadalupe Amancio 1 , Armando Aguirre-Jaimes 1, Vicente Hernández-Ortiz 1,* , Roger Guevara 2 and Mauricio Quesada 3,4 1 Red de Interacciones Multitróficas, Instituto de Ecología A.C., Xalapa, Veracruz 91073, Mexico 2 Red de Biologia Evolutiva, Instituto de Ecología A.C., Xalapa, Veracruz 91073, Mexico 3 Laboratorio Nacional de Análisis y Síntesis Ecológica, Escuela Nacional de Estudios Superiores Unidad Morelia, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Morelia 58190 Michoacán, Mexico 4 Instituto de Investigaciones en Ecosistemas y Sustentabilidad, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Morelia 58190 Michoacán, Mexico * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 June 2019; Accepted: 9 August 2019; Published: 15 August 2019 Abstract: Insect-aroid interaction studies have focused largely on pollination systems; however, few report trophic interactions with other herbivores. This study features the endophagous insect community in reproductive aroid structures of a tropical rainforest of Mexico, and the shifting that occurs along an altitudinal gradient and among different hosts. In three sites of the Los Tuxtlas Biosphere Reserve in Mexico, we surveyed eight aroid species over a yearly cycle. The insects found were reared in the laboratory, quantified and identified. Data were analyzed through species interaction networks. We recorded 34 endophagous species from 21 families belonging to four insect orders. The community was highly specialized at both network and species levels. Along the altitudinal gradient, there was a reduction in richness and a high turnover of species, while the assemblage among hosts was also highly specific, with different dominant species. -

Animal Conflict "1,

ANIMAL CONFLICT "1, ...... '", .. r.", . r ",~ Illustrated by Leslie M. Downie Department of Zoology, University of Glasgow ANIMAL CONFLICT Felicity A. Huntingford and Angela K. Turner Department of Zoology, University of Glasgow .-~ ' ..... '. .->, I , f . ~ :"fI London New York CHAPMAN AND HALL Chapman and Hall Animal Behaviour Series SERIES EDITORS D.M. Broom Colleen Macleod Professor of Animal Welfare, University of Cambridge, UK P.W. Colgan Professor of Biology, Queen's University, Canada Detailed studies of behaviour are important in many areas of physiology, psychology, zoology and agriculture. Each volume in this series will provide a concise and readable account of a topic of fundamental importance and current interest in animal behaviour, at a level appropriate for senior under graduates and research workers. Many facets of the study ofanimal behaviour will be explored and the topics included will reflect the broad scope of the subject. The major areas to be covered will range from behavioural ecology and sociobiology to general behavioural mechanisms and physiological psychology. Each volume will provide a rigorous and balanced view of the subject although authors will be given the freedom to develop material in their own way. To Tim) Joan and Jessica) with thanks) and to all the children who provided inspiration First published in 1987 by Chapmatl and Hall Ltd 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Published in the USA by Chapman atld Hall 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 © 1987 Felicity A. Huntingford and Angela K. Turner Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1987 ISBN -13: 978-94-010-9008-7 This title is available in both hardbound and paperback editions. -

Variability of Large Marine Ecosystems in Response to Global Climate Change

Sherman et al. ICESCM 2007/D:20 ICES CM 2007/D:20 Variability of Large Marine Ecosystems in response to global climate change K. Sherman, I. Belkin, J. O’Reilly and K. Hyde Kenneth Sherman, John O’Reilly, Kimberly Hyde USDOC/NOAA, NMFS Narragansett Laboratory 28 Tarzwell Drive Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882 USA +1 401-782-3210 phone +1 401 782-3201 FAX [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Igor Belkin Graduate School of Oceanography University of Rhode Island 215 South Ferry Road Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882 USA +1 401 874-6728 phone +1 401 874-6728 FAX [email protected] Abstract: A fifty year time series of sea surface temperature (SST) and time series on fishery yields are examined for emergent patterns relative to climate change. More recent SeaWiFS derived chlorophyll and primary productivity data were also included in the examination. Of the 64 LMEs examined, 61 showed an emergent pattern of SST increases from 1957 to 2006, ranging from mean annual values of 0.08°C to 1.35°C. The rate of surface warming in LMEs from 1957 to 2006 is 4 to 8 times greater than the recent estimate of the Japan Meteorological Society’s COBE estimate for the world oceans. Effects of SST warming on fisheries, climate change, and trophic cascading are examined. Concern is expressed on the possible effects of surface layer warming in relation to thermocline formation and possible inhibition of vertical nutrient mixing within the water column in relation to bottom up effects of chlorophyll and primary productivity on global fisheries resources. -

Measuring Plant Dominance

Measuring Plant Dominance I. Definition = measure of the relative importance of a plant species with repsect to the degree of influence that the species exerts on the other components (e.g., other plants, animal, soils) of the community. A. Influence based on competition for resources (e.g., light, water, nutrients) B. Difficult to measure influence below ground so dominance is usually estimated with above ground characteristics. II. Types of Dominance A. Aspect dominance: 1. Tallest layer is the dominant layer (reduces climatic extremes by intercepting light and precipitation, reducing wind velocity, and retaining heat). 2. Limitation: Ignores an understory that may be changing while the dominant plant remains the same B. Sociologic dominance 1. Used when interested in understory dominance. (Often used when overstory is constant and unchanging). 2. Limitation: doesn’t work well in systems with diverse overstory species C. Relative dominance 1. Examines the dominant species in each layer of the plant community 2. Useful for multiple use management (overcomes limitations of first two types) III. Why monitory dominance? A. Dominant species are often used to identify or classify and ecological type (e.g., Art.tri/Agr.spi. habitat type). B. If the dominant spp are identified, one can predict changes that may occur in response to long-term precipitation changes or disease. C. If the dominant spp are identified, management options can be more clearly understood. D. Can be used in long-term monitoring programs to determine if management or preservation regimes are positively affecting the ecosystem. IV. Evaluating dominance: A. Can be a single species, a group of species, or and entire growth form B. -

A Review of Some Aspects of Avian Field Ethology 1

A REVIEW OF SOME ASPECTS OF AVIAN FIELD ETHOLOGY 1 ROBERT W. FICKEN AND MILLICENT S. FICKEN T•E last 30 yearshave seen the developmentof a new approachto the study of behavior, which has increasinglyinterested ornithologists as they have attemptedto understandavian biologyfully. This new ap- proachis now known as ethology. Both amateur and professionalorni- thologistshave contributedto its progressfrom the beginning. A basictenet of ethologyis that all behaviorof animalscan eventually be understood.The ethologistattempts to explainbehavior functionally (what doesit do for the animal?), causally(what are the internal and externalfactors responsible for each given behavior?),and evolutionarily (what is the probablephylogeny of the behavior,how doesit contribute to th'esurvival of the species,and what are the selectivepressures acting uponit?) (seeTinbergen, 1951, 1959; Hinde, 1959b). Somebasic proceduresare essentialin an ethologicalstudy (Hinde, 1959b: 564). The first step is to describeand classifyall the behavior of an animal, at the same time, if possible,dividing the behavior into logicalunits which can be dealt with furtherin other disciplines--particu- larly physiologyand ecology(see Russellet al., 1954). Althoughstudies often beginqualitatively, they eventuallyshould be quantified. Generali- zations,which are to be valid for many species,must be basedon work using closelyrelated speciesfirst, and more distantly related ones later. The animal is studied as an integrated whole. Some workers, notably Konrad Lorenz, keep and breed animalsin captivity under closescrutiny. Most of this paper dealswith communicationof birds. We have stressed particularly the analysisof displays,their evolution,and their relation to taxonomy--topicsof great interest to systematicornithologists as well as to ethologists.In addition, we discusscertain maintenanceactivities. LITERATURE OF ET•OLOC¾ Much of the early ethologicalliterature appearedin Europeanpublications, but it is now also appearingin this country frequently. -

Lakes: Ann, Gilchrist, Grove, Leven, Reno, Villard, Smith)

Status and Trend Monitoring Summary for Selected Pope and Douglas County, Minnesota Lakes 2000 (Lakes: Ann, Gilchrist, Grove, Leven, Reno, Villard, Smith) Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Environmental Outcomes Division Environmental Monitoring and Analysis Section Andrea Plevan and Steve Heiskary September 2001 Printed on recycled paper containing at least 10 percent fibers from paper recycled by consumers. This material may be made available in other formats, including Braille, large format and audiotape. MPCA Status and Trend Monitoring Summary for 2000 Pope County Lakes Part 1: Purpose of study and background information on MN lakes The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency’s (MPCA) core lake-monitoring programs include the Citizen Lake Monitoring Program (CLMP), the Lake Assessment Program (LAP), and the Clean Water Partnership (CWP) Program. In addition to these programs, the MPCA annually monitors numerous lakes to provide baseline water quality data, provide data for potential LAP and CWP lakes, characterize lake conditions in different regions of the state, examine year-to-year variability in ecoregion reference lakes, and provide additional trophic status data for lakes exhibiting trends in Secchi transparency. In the latter case, we attempt to determine if the trends in Secchi transparency are “real,” i.e., if supporting trophic status data substantiate whether a change in trophic status has occurred. The lake sampling efforts also provide a means to respond to citizen concerns about protecting or improving the lake in cases where no data exists to evaluate the quality of the lake. For efficient sampling, we tend to select geographic clusters of lakes (e.g., focus on a specific county) whenever possible. -

Aggressive Behavior in the Genus Gallus Sp1

Brazilian Journal of Poultry Science Revista Brasileira de Ciência Avícola ISSN 1516-635X Jan - Mar 2006 / v.8 / n.1 / 01 - 14 Aggressive behavior in the genus Gallus sp1 Author(s) ABSTRACT Queiroz SA2 The intensification of the production system in the poultry industry Cromberg VU3 and the vertical integration of the poultry agribusiness have brought 1 Funded by Associação de Criadores e de profound changes in the physical and social environment of domestic Preservação das Raças de Galos Combatentes. fowls in comparison to their ancestors and have modified the expression 2 Departamento de Zootecnia, Faculdade de of aggression and submission. The present review has covered the Ciências Agrárias e Veterinárias de studies focusing on the different aspects linked to aggressiveness in Jaboticabal, Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP) the genus Gallus. The evaluated studies have shown that aggressiveness 3 ETCO Grupo de Estudos e Pesquisa em and subordination are complex behavioral expressions that involve Etologia e Ecologia - UNESP/FCAV genetic differences between breeds, strains and individuals, and differences in the cerebral development during growth, in the hormonal metabolism, in the rearing conditions of individuals, including feed restriction, density, housing type (litter or cage), influence of the opposite Mail Address sex during the growth period, existence of hostile stimuli (pain and Sandra Aidar de Queiroz frustration), ability to recognize individuals and social learning. The Departamento de Zootecnia utilization of fighting birds as experimental material in the study of Faculdade de Ciências Agrárias e Veterinárias de Jaboticabal - UNESP mechanisms that have influence on the manifestation of aggressiveness Via de acesso Prof. Paulo D. -

Human Domination of Earth's Ecosystems Peter M

: . - : :: : . .. :: .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. ...... ........ .. .... ..... ...... .. ... ... .... ... ..:. : .: :. : :::. ..:. :. .. ...5 .::.X'jC:' jj : 00 ,: ;; ;dA SV D ) 0 Sa C::: dS:: : :'; .SS;d. ;id)fV A .:Q ....;: ..:: ....; .: .: ..0 .....:: Human Domination of Earth's Ecosystems Peter M. Vitousek, HaroldA. Mooney, Jane Lubchenco, Jerry M. Melillo Humanalteration of Earthis substantialand growing. Between one-thirdand one-half interactwith the atmosphere,with aquatic of the land surface has been transformedby human action; the carbon dioxide con- systems,and with surroundingland. More- centrationin the atmosphere has increased by nearly30 percent since the beginningof over, land transformationinteracts strongly the IndustrialRevolution; more atmospheric nitrogen is fixed by humanitythan by all with most other componentsof global en- naturalterrestrial sources combined;more than halfof all accessible surface fresh water vironmentalchange. is put to use by humanity;and about one-quarterof the birdspecies on Earthhave been The measurementof land transforma- drivento extinction. By these and other standards, it is clear that we live on a human- tion on a globalscale is challenging;chang- dominated planet. es can be measuredmore or less straightfor- wardly at a given site, but it is difficult to aggregatethese changesregionally and glo- bally. In contrastto analysesof human al- Aii organismsmodify their environment, reasonablywell quantified;all are ongoing. teration of the global carbon cycle, we and humans are no exception.