Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Endemic Ducks of Remote Islands DAVID LACK Introduction with the Names and Measurements of the Resident Forms of Anas

Ducks of remote islands 5 The endemic ducks of remote islands DAVID LACK Introduction with the names and measurements of the resident forms of Anas. On large islands This paper is concerned with all those and on islands near continents many ducks which have formed distinctive sub species of ducks coexist. For instance, 13 species restricted to one particular small species, 7 in the genus Anas, breed regu and remote island or archipelago. Only larly in Britain (Parslow 1967), 16 species, dabbling ducks in the genus Anas are 6 in the genus Anas, in Iceland (F. involved. Many species in this genus have Gudmundsson pers, com.), 8, 5 in the an extremely wide range, but the average genus Anas, in the Falkland Islands number of subspecies per species is as (Cawkell and Hamilton 1961) and 7, with low as 1.9 for the 38 species recognised 2 more in the nineteenth century, 4 in the by Delacour (1954-64). Hence the fact genus Anas, in New Zealand (Williams that nearly all the ducks on remote small 1964). Some of the Falklands and New islands are separate subspecies means that, Zealand forms are endemic, not so those for ducks, they belong to relatively of British or Iceland. Although the isolated populations. In contrast, on some various species of ducks look superficially of the archipelagos concerned, notably alike, especially when seen together in a the Hawaiian Islands and Galapagos, collection of living waterfowl, they have various of the land birds are distinctive in fact evolved an adaptive radiation species or even genera. -

Lista Roja De Las Aves Del Uruguay 1

Lista Roja de las Aves del Uruguay 1 Lista Roja de las Aves del Uruguay Una evaluación del estado de conservación de la avifauna nacional con base en los criterios de la Unión Internacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza. Adrián B. Azpiroz, Laboratorio de Genética de la Conservación, Instituto de Investigaciones Biológicas Clemente Estable, Av. Italia 3318 (CP 11600), Montevideo ([email protected]). Matilde Alfaro, Asociación Averaves & Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de la República, Iguá 4225 (CP 11400), Montevideo ([email protected]). Sebastián Jiménez, Proyecto Albatros y Petreles-Uruguay, Centro de Investigación y Conservación Marina (CICMAR), Avenida Giannattasio Km 30.5. (CP 15008) Canelones, Uruguay; Laboratorio de Recursos Pelágicos, Dirección Nacional de Recursos Acuáticos, Constituyente 1497 (CP 11200), Montevideo ([email protected]). Cita sugerida: Azpiroz, A.B., M. Alfaro y S. Jiménez. 2012. Lista Roja de las Aves del Uruguay. Una evaluación del estado de conservación de la avifauna nacional con base en los criterios de la Unión Internacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza. Dirección Nacional de Medio Ambiente, Montevideo. Descargo de responsabilidad El contenido de esta publicación es responsabilidad de los autores y no refleja necesariamente las opiniones o políticas de la DINAMA ni de las organizaciones auspiciantes y no comprometen a estas instituciones. Las denominaciones empleadas y la forma en que aparecen los datos no implica de parte de DINAMA, ni de las organizaciones auspiciantes o de los autores, juicio alguno sobre la condición jurídica de países, territorios, ciudades, personas, organizaciones, zonas o de sus autoridades, ni sobre la delimitación de sus fronteras o límites. -

Rockjumper Birding

Eastern South Africa & Cape Extension III Trip Report 29thJune to 17thJuly 2013 Orange-breasted Sunbird by Andrew Stainthorpe Trip report compiled by tour leader Andrew Stainthorpe Top Ten Birds seen on the tour as voted by participants: 1. Drakensberg Rockjumper 2. Orange-breasted Sunbird 3. Purple-crested Turaco 4. Cape Rockjumper 5. Blue Crane Trip Report - RBT SA Comp III June/July 2013 2 6. African Paradise Flycatcher 7. Long-crested Eagle 8. Klaas’s Cuckoo 9. Black Harrier 10. Malachite Sunbird. Eastern South Africa, with its diverse habitats and amazing landscapes, holds some truly breath-taking birds and game-rich reserves, and this was to be the main focus of our tour, with a short yet endemic-filled extension to the Western Cape. Commencing in busy Johannesburg, it was not long after we set off before we began ticking our first common birds for the tour, with an attractive pair of Red-headed Finches being a nice early bonus. Arriving at a productive small pan a while later, we found good numbers of water birds including Great Crested Grebe, African Swamphen, Cape Shoveler, Yellow-billed Duck, Greater Flamingo, Black-crowned Night Heron and Black-winged Stilt. We then made our way to the arid “thornveld” woodlands to the northeast of Pretoria and this certainly produced a good number of the more arid species right on their eastern limits of distribution. Some of the better birds seen in this habitat were the gaudy Crimson-breasted Shrike, Southern Pied Babbler, Black-faced Waxbill, Kalahari Scrub Robin, Chestnut-vented Warbler (Tit-babbler) and Greater Kestrel. -

Courtship of Ducklings by Adult Male Chiloe Wigeon (Anas Sibilatrix)

October 1991] ShortCommunications 969 Natural Environment ResearchCouncil grant GR3/ LINDEN, M., & A. P. MOLLERß 1989ß Cost of repro- 7249. duction and covariation of life history traits in birds. Trends Ecol. Evol. 4: 367-371. LITERATURE CITED NUR, N. 1984. The consequencesof brood size for breeding Blue Tits I. Adult survival, weight ASKENIVIO,C. 1979. Reproductiverate and the return change and the cost of reproduction. J. Anim. rate of male Pied Flycatchers.Am. Nat. 114:748- Ecol. 53: 479-496ß 753. 1988a. The consequencesof brood size for COHEN,J. 1988. Statistical power analysis for the breeding Blue Tits III. Measuring the cost of re- behavioral sciences,second ed. New Jersey,Law- production: survival, future fecundity and dif- rence Erlbaum Assoc. ferential dispersalßEvolution 42: 351-362ß DESTEvEN,D. 1980. Clutch size, breeding success ß 1988b. The costof reproduction in birds: an and parental survival in the Tree Sparrow (Iri- examination of the evidenceß Ardea 76: 155-168. doprocnebicolor). Evolution 34: 278-291. --. 1990. The costof reproduction in birds, eval- DIJKSTRA,C., A. BULT, S. BIJLSMA,S. D^AN, T. MEIJER, uating the evidence from manipulative and non- • g. ZIJLSTRA.1990. Brood size manipulations manipulative studies. In Population biology of in the Kestrel (Falco tinnunculus):effects on off- passerinebirds, an integratedapproach (J. Blon- spring and parent survival. J.Anim. Ecol.59: 269- del, A. Gosler,J. D. Lebreton,and R. McCleery, 285. Eds.).Berlin, Springer-VerlagPressß FLEISS,J. L. 1981. Statistical methods for rates and ORELL,M., & K. KOIVULA. 1988. Costof reproduction: proportions, second ed. New York, J. Wiley and parental survival and production of recruits in Sons. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Journal of Avian Biology 48:640-648

Journal of Avian Biology 48: 640–649, 2017 doi: 10.1111/jav.00998 © 2016 The Authors. Journal of Avian Biology © 2016 Nordic Society Oikos Subject Editor: Darren Irwin. Editor-in-Chief: Thomas Alerstam. Accepted 2 October 2016 Divergence and gene flow in the globally distributed blue-winged ducks Joel T. Nelson, Robert E. Wilson, Kevin G. McCracken, Graeme S. Cumming, Leo Joseph, Patrick-Jean Guay and Jeffrey L. Peters J. T. Nelson and J. L. Peters, Dept of Biological Sciences, Wright State Univ., Dayton, OH, USA. – R. E. Wilson ([email protected]), U. S. Geological Survey, Alaska Science Center, Anchorage, AK, USA. – K. G. McCracken and REW, Inst. of Arctic Biology, Dept of Biology and Wildlife, and Univ. of Alaska Museum, Univ. of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK, USA. KGM also at: Dept of Biology and Dept of Marine Biology and Ecology, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Univ. of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, USA. – G. S. Cumming, Percy FitzPatrick Inst., DST/NRF Centre of Excellence, Univ. of Cape Town, Rondebosch, South Africa, and ARC Centre of Excellence in Coral Reef Studies, James Cook Univ., Townsville, QLD, Australia. – L. Joseph, Australian National Wildlife Collection, National Research Collections Australia, CSIRO, Canberra, ACT, Australia. – P.-J. Guay, Inst. for Sustainability and Innovation, College of Engineering and Science, Victoria Univ., Melbourne, VIC, Australia. The ability to disperse over long distances can result in a high propensity for colonizing new geographic regions, including uninhabited continents, and lead to lineage diversification via allopatric speciation. However, high vagility can also result in gene flow between otherwise allopatric populations, and in some cases, parapatric or divergence-with-gene-flow models might be more applicable to widely distributed lineages. -

Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Sources Cited Alder, L. P. 1963. The calls and displays of African and In Bellrose, F. C. 1976. Ducks, geese and swans of North dian pygmy geese. In Wildfowl Trust, 14th Annual America. 2d ed. Harrisburg, Pa.: Stackpole. Report, pp. 174-75. Bellrose, F. c., & Hawkins, A. S. 1947. Duck weights in Il Ali, S. 1960. The pink-headed duck Rhodonessa caryo linois. Auk 64:422-30. phyllacea (Latham). Wildfowl Trust, 11th Annual Re Bengtson, S. A. 1966a. [Observation on the sexual be port, pp. 55-60. havior of the common scoter, Melanitta nigra, on the Ali, S., & Ripley, D. 1968. Handbook of the birds of India breeding grounds, with special reference to courting and Pakistan, together with those of Nepal, Sikkim, parties.] Var Fagelvarld 25:202-26. -

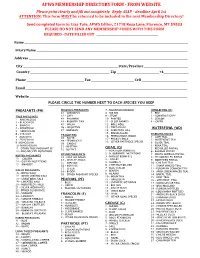

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - from WEBSITE Please Print Clearly and Fill out Completely

APWS MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - FROM WEBSITE Please print clearly and fill out completely. Reply ASAP – deadline April 1st ATTENTION: This form MUST be returned to be included in the next Membership Directory! Send completed form to: Lisa Tate, APWS Editor, 21718 Kesa Lane, Florence, MT 59833 PLEASE DO NOT SEND ANY MEMBERSHIP FUNDS WITH THIS FORM REQUIRED - DATE FILLED OUT ______________________________________________ Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Aviary Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Address _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ City ________________________________________________________________________ State/Province _________________________________ Country ___________________________________________________________ Zip ________________________________+4___________________ Phone ___________________________________________ Fax ________________________________ Cell __________________________________ Email _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Website ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PLEASE CIRCLE THE NUMBER NEXT TO EACH SPECIES YOU KEEP PHEASANTS (PH) PEACOCK-PHEASANTS 7 - MOUNTAIN BAMBOO JUNGLEFOWL -

An Introduction to the Bofedales of the Peruvian High Andes

An introduction to the bofedales of the Peruvian High Andes M.S. Maldonado Fonkén International Mire Conservation Group, Lima, Peru _______________________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY In Peru, the term “bofedales” is used to describe areas of wetland vegetation that may have underlying peat layers. These areas are a key resource for traditional land management at high altitude. Because they retain water in the upper basins of the cordillera, they are important sources of water and forage for domesticated livestock as well as biodiversity hotspots. This article is based on more than six years’ work on bofedales in several regions of Peru. The concept of bofedal is introduced, the typical plant communities are identified and the associated wild mammals, birds and amphibians are described. Also, the most recent studies of peat and carbon storage in bofedales are reviewed. Traditional land use since prehispanic times has involved the management of water and livestock, both of which are essential for maintenance of these ecosystems. The status of bofedales in Peruvian legislation and their representation in natural protected areas and Ramsar sites is outlined. Finally, the main threats to their conservation (overgrazing, peat extraction, mining and development of infrastructure) are identified. KEY WORDS: cushion bog, high-altitude peat; land management; Peru; tropical peatland; wetland _______________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION organic soil or peat and a year-round green appearance which contrasts with the yellow of the The Tropical Andes Cordillera has a complex drier land that surrounds them. This contrast is geography and varied climatic conditions, which especially striking in the xerophytic puna. Bofedales support an enormous heterogeneity of ecosystems are also called “oconales” in several parts of the and high biodiversity (Sagástegui et al. -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

Cattleegret for PDF 2.Jpg

Chestnut Teal count The Whistler 5 (2011): 51-52 Chestnut Teal count – March 2011 Ann Lindsey1 and Michael Roderick2 137 Long Crescent, Shortland, NSW 2037, Australia [email protected] 256 Karoola Road, Lambton, NSW 2299, Australia [email protected] In March 2011, 4,497 Chestnut Teal Anas castanea were counted during a comprehensive survey of the Hunter Estuary and other wetlands in the Lower Hunter and Lake Macquarie areas. 4,117 Chestnut Teal, which is >4% of the Australian population, occurred in the estuary. The importance of the Hunter Estuary Important Bird Area (IBA) to Chestnut Teal was confirmed. On 18 March 2011 during a regular monthly in the Hunter Estuary and at other sites in the survey as part of the Hunter Shorebird Surveys, Lower Hunter and Lake Macquarie. The number of Mick Roderick counted 1,637 Chestnut Teal Anas sites surveyed was limited by the number of castanea at Deep Pond on Kooragang Island. participants. The time chosen coincided Subsequently, on 26 March 2011, Ann Lindsey approximately with the high tide at Stockton visited the eastern side of Hexham Swamp and Bridge, consistent with the protocols of the counted 1,200 Chestnut Teal. The question arose monthly Hunter Shorebird Surveys. It also as to whether these counts involved the same birds coincided with a time (early afternoon) when or whether they were in fact separate flocks. waterfowl are least active. Much of the 8,453ha Hunter Estuary (32o 52' / 151o Nineteen sites were surveyed by eleven people 45') is designated as an Important Bird Area (IBA) between 1230 and 1520 hours on the day (Table as it meets several of the necessary criteria.