Work, Gender, and Generational Change: an Ethnography of Human-Environment Relations in a Bahun Village, Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Crisis of Caste Renouncer: a Study of Dasnami Sanyasi Identity in Nepal

Molung Educational Frontier 91 Cultural Crisis of Caste Renouncer: A Study of Dasnami Sanyasi Identity in Nepal Madhu Giri* Abstract Jat NasodhanuJogikois a famous mocking proverb to denote the caste status of Sanyasi because the renouncer has given up traditional caste rituals set by socio-cultural institutions. In other cultural terms, being Sanyasi means having dissociation himself/herself with whatever caste career or caste-based social rank one might imagine. To explore the philosophical foundation of Sanyasi, they sacrificed caste rituals and fire (symbol of power, desire, and creation). By the virtues of sacrifice, Sanyasi set images of universalism, higher than caste order, and otherworldly being. Therefore, one should not ask the renouncer caste identity. Traditionally, Sanyasi lived in Akhada or Matha,and leadership, including ownership of the Matha transformed from Guru to Chela. On the contrary, DasnamiMahanta started marital and private life, which is paradoxical to the philosophy of Sanyasi.Very few of them are living in Matha,but the ownership of the property of Mathatransformed from father to son. The land and property of many Mathas transformed from religious Guthi to private property. In terms of cultural practices, DasnamiSanyasi adopted high caste culture and rituals in their everyday life. Old Muluki Ain 1854 ranked them under Tagadhari, although they did notassert twice-born caste in Nepal. Central Bureau of Statistics, including other government institutions of Nepal, listed Dasnamiunder the line ofChhetri and Thakuri. The main objective of the paper is to explore the transformation of Dasnami institutional characteristics and status from caste renunciation identity to caste rejoinder and from images of monasticism, celibacy, universalism, otherworldly orientation to marital, individualistic lay life. -

Nepali Times, #185) Vicinity

#220 5 - 11 November 2004 20 pages Rs 25 SILVER LINING: An uplifting Kathmandu Valley sunset on Wednesday was not reflected on the political horizon. p10-11 Birds of a feather Weekly Internet Poll # 160 Q. Which US presidential candidate would be better for the world? Total votes:1,202 Weekly Internet Poll # 161. To vote go to: www.nepalitimes.com Q. Should the pre-2002 parliament be reinstated? KUNDA DIXIT ANALYSIS by PUSKAR GAUTAM he recent escalation of T Maoist rhetoric over an impending Indian invasion is being followed up Tunnel vision with frenzied tunnel-digging throughout the country, Nepals Maoists are literally going underground ostensibly to thwart Indian air raids. to spread revolution in the region The tunnels are symbolic of the rebel leaderships change of In their analysis, poverty, Even so, the Nepali com- mechanism and phases of the focus towards external enemies: ethnic exclusion, and rades are taking advantage of poll process. And it wont be US imperialism and Indian topography make the Himalayan continuing political disarray in life-or-death for the Maoists if expansionism. The leadership arc ideal for a trans-boundary Kathmandu and see an opening polls do happen, they will not and cadre are at present busy in revolution in which guerrillas in the Deuba governments push try to launch unnecessarily military and political training, can move freely across borders. for elections by April 2005. They costly offensives during it. and believe their strategic They want to convert the ethno- expect an election will further Deuba is obviously laying the offensive within Nepal will not separatist agenda of militants in polarise the parties and split the groundwork for elections with be successful unless the the Indian northeast to fight a anti-regression alliance. -

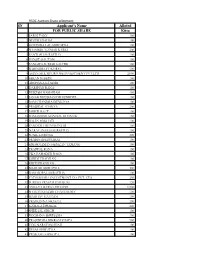

Applicant's Name Alloted for PUBLIC SHARE Kitta

RSDC Auction Share Allotment SN Applicant's Name Alloted FOR PUBLIC SHARE Kitta 1 SAROJ PANT 200 2 NITESH DAHAL 100 3 GOVINDA LAL SHRESTHA 100 4 SHAMBHU KUMAR KARKI 200 5 SANTOSH SHRESTHA 100 6 RANJIT GAUTAM 150 7 SANGITA SUBEDI KHATRI 100 8 RABINDRA POKHREL 100 9 ASIAN MULTIPURPOSE INVESTMENT PVT.LTD. 2,000 10 KIRAN SUBEDI 160 11 ARCHANA KUMARI 100 12 DARSHAN RANA 100 13 RUKESH MAHARJAN 450 14 JANAK BHUSHAN DHAUBHDEL 100 15 RAM CHANDRA DEVKOTA 100 16 PRAJJWAL SHAKYA 200 17 SMRITI RAUT 100 18 RAMASHISH MANDAL DHANUK 150 19 RAJAN BAKHATI 100 20 SANDESH DHAUBANJAR 100 21 NARAYAN DAS SHRESTHA 150 22 SUNIL GURUNG 300 23 PRABIN BHATTARAI 100 24 KRISHNAMAN HEMZAN TAMANG 100 25 PRAJWAL RANA 100 26 EKA BAHADUR RANA 100 27 SMRITI PRADHAN 100 28 KRITI PRADHAN 100 29 MAHESH SHRESTHA 300 30 RAM GOPAL SHRESTHA 100 31 PATHIBHARA INVESTMENT CO. PVT. LTD. 250 32 SURESH PRASAD PARAJULI 120 33 AMULYA RATNA STHAPIT 1,500 34 SHAKTI KUMARI CHAUDHARY 100 35 MADHAV GAUTAM 100 36 PRASSANNA SHAKYA 200 37 KAMALA DHAKAL 220 38 SHEETAL SINGH 100 39 ROCHANA SHRESTHA 200 40 PRASIDDHA BIKRAM THAPA 500 41 YOG NARAYAN SHAH 100 42 DIBAS SHRESTHA 100 43 PRAKASH SAPKOTA 100 44 BINU POUDEL THAPA 210 45 SHAKTI AMAR SINGH 250 46 NAWRAJ SIGDEL 150 47 KUL BAHADUR PANDIT 240 48 RAVINDRA ACHARYA 200 49 RAM MANOHAR SHRESTHA 100 50 BASANT KUMAR MISHRA 100 51 JOON SHRESTHA 200 52 PRATAP MAN SHRESTHA 500 53 DURGA BAHADUR BANIYA 1,500 54 GUHESWORI MERCHANT BANKING AND FINANCE 5,000 55 MUNA DEVI RAWAL 100 56 KUSUM SHRESTHA 100 57 CHHABILAL GYAWALI 550 58 YOGA RAJ JOSHI 100 59 NABINDRA -

The Politics of Culture and Identity in Contemporary Nepal

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 20 Number 1 Himalayan Research Bulletin no. 1 & Article 7 2 2000 Roundtable: The Politics of Culture and Identity in Contemporary Nepal Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation . 2000. Roundtable: The Politics of Culture and Identity in Contemporary Nepal. HIMALAYA 20(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol20/iss1/7 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Roundtable: The Politics of Culture and Identity in Contemporary Nepal Organizers: William F. Fisher and Susan Hangen Panelists: Karl-Heinz Kramer, Laren Leve, David Romberg, Mukta S. Tamang, Judith Pettigrew,and Mary Cameron William F. Fisher and Susan Hangen local populations involved in and affected by the janajati Introduction movement in Nepal. In the years since the 1990 "restoration" of democracy, We asked the roundtable participants to consider sev ethnic activism has become a prominent and, for some, a eral themes that derived from our own discussion: worrisome part of Nepal's political arena. The "janajati" 1. To what extent and to what end does it make sense movement is composed of a mosaic of social organizations to talk about a "janajati movement"? Reflecting a wide and political parties dominated by groups of peoples who variety of intentions, goals, definitions, and strategies, do have historically spoken Tibeto-Burman languages. -

Agnihotra-Rituals-FINAL Copy

Agnihotra Rituals in Nepal The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Witzel, Michael. 2015. "Agnihotra Rituals in Nepal." In Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée, eds. Richard K. Payne and Michael Witzel, 371. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199351572.003.0014 Published Version doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199351572.003.0014 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:34391774 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP Michael Witzel AGNIHOTRA RITUALS IN NEPAL Five* groups of Brahmins reside in the Kathmandu Valley of today:1 the Newari speaking Rājopādhyāya, the Nepali speaking Pūrbe, who immigrated in the last centuries before and the Gorkha conquest (1768/9 CE), the Kumaĩ, the Newari and Maithili speaking Maithila, and the Bhaṭṭas from South India, who serve at the Paśupatināth temple. Except for the Bhaṭṭas, all are followers of the White Yajurveda in its Mādhyandina recension. It could therefore be expected that all these groups, with the exception of the Bhaṭṭas, would show deviations from each other in language and certain customs brought from their respective homelands, but that they would agree in their (Vedic) ritual. However, this is far from being the case. On the contrary, the Brahmins of the Kathmandu Valley, who have immigrated over the last fifteen hundred years in several waves,2 constitute a perfect example of individual regional developments in this border area of medieval Indian culture, as well as of the successive, if fluctuating, influence of the ‘great tradition’ of Northern India. -

Cultural Capital and Entrepreneurship in Nepal: the Readymade Garment Industry As a Case Study

Cultural Capital and Entrepreneurship in Nepal: The Readymade Garment Industry as a Case Study Mallika Shakya Development Studies Institute (DESTIN) February 2008 Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by the University of London UMI Number: U613401 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U613401 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 O^lJbraryofPeMic. find Economic Science Abstract This thesis is an ethnographic account of the modem readymade garment industry in Nepal which is at the forefront of Nepal’s modernisation and entry into the global trade system. This industry was established in Nepal in 1974 when the United States imposed country-specific quotas on more advanced countries and flourished with Nepal’s embrace of economic liberalisation in the 1990s. Post 2000 however, it faced two severe crises: the looming 2004 expiration of the US quota regime which would end the preferential treatment of Nepalese garments in international trade; and the local Maoist insurgency imposed serious labour and supply chain hurdles to its operations. -

Nationalism and Regional Relations in Democratic Transitions: Comparing Nepal and Bhutan

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2018 Nationalism and Regional Relations in Democratic Transitions: Comparing Nepal and Bhutan Deki Peldon Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the International Relations Commons Repository Citation Peldon, Deki, "Nationalism and Regional Relations in Democratic Transitions: Comparing Nepal and Bhutan" (2018). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 1981. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/1981 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATIONALISM AND REGIONAL RELATIONS IN DEMOCRATIC TRANSITIONS: COMPARING NEPAL AND BHUTAN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By DEKI PELDON Bachelor of Arts, Asian University for Women, 2014 2018 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL [May 4, 2018] I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY DEKI PELDON ENTITLED NATIONALISM AND REGIONAL RELATIONS IN DEMOCRATIC TRANSITIONS: COMPARING NEPAL AND BHUTAN BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS. Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. Thesis Director Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. Director, Master of Arts Program in International and Comparative Politics Committee on Final Examination: Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs Pramod Kantha, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs Judson Murray, Ph.D. -

Nepalese Buddhists' View of Hinduism 49

46 Occasional Papers Krauskopff, Gis"le and Pamela D. Mayer, 2000. The Killgs of Nepal alld the Tha", of the Tarai. Kirlipur: Research Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies (CNAS). KrnuskoplT, Gis"le, 1999. Corvees in Dang: Ethno-HislOrical Notes, Pp. 47-62, In Harald O. Skar el. al. (eds.), Nepal: Tharu alld Tarai NEPALESE BUDDHISTS' Neighbours. Kathmandu: EMR. VIEW OF HINDUISM l Lowe, Peter, 2001. Kamaiya: Slavery and Freedom in Nepal. Kathmandu: Mandala Book Point in Association with Danish Association for Krishna B. Bhattachan International Cooperalion (MS Nepal). MUller-Boker, Ulrike, 1999. The Chitwall Tharus ill Southern Nepal: All Introduction EthnoecoJogical Approach. Franz Stiner Verlag Stuttgart 0degaard, Sigrun Eide. 1999. Base and the Role of NGO in the Process of Nepal is a multi-caste/ethnic, multi-lingual, multi-cultural and Local and Regional Change, Pp. 63-84, In Harald O. Skar (ed.l. multi-religious country. The Hindu "high castes" belong to Nepal: Tha", alld Tal'lli Neighbours. Kathmandu: EMR. Caucasoid race and they are divided into Bahun/Brahmin, Chhetri/ Rankin, Katharine, 1999. Kamaiya Practices in Western Nepal: Kshatriya, Vaisya and Sudra/Dalits and the peoples belonging to Perspectives on Debt Bondage, Pp. 27-46, In Harald O. Skar the Hill castes speak Nepali and the Madhesi castes speak various (ed.), Nepal: Tharu alld Tarai Neighbours. Kathmandu: EMR. mother tongues belonging to the same Indo-Aryan families. There Regmi, M.C., 1978. Land Tenure and Taxation in Nepal. Kathmandu: are 59 indigenous nationalities of Nepal and most of them belong to Ratna Pustak. Mongoloid race and speak Tibeto-Bumnan languages. -

Nepali Times Welcomes All Feedback

#270 28 October - 3 November 2005 16 pages Rs 30 Weekly Internet Poll # 270 Q... Should the political parties participate in municipal and general elections? Total votes:5,012 Press under pressure The crackdown on Kantipur is to show the regime has teeth but it may have bitten off more than it can chew Weekly Internet Poll # 271. To vote go to: www.nepalitimes.com KUNDA DIXIT Indeed, some of the provisions of appear free but the media gag rule statements by officials that Q... Should news be allowed on FM radios the royal decree, such as hangs like a sword over our nowhere in the world is news in Nepal? he persecution of Kantipur restrictions on cross-ownership, a heads.” Indeed, the sword now allowed on FM has made them a this week may have been the code of conduct for journalists and seems to have fallen on Kantipur laughing stock. The media T royal regime’s way of even the ban on news on FM, were FM as punishment for its fiercely ordinance has also severely showing it means business with its tabled by the elected Deuba critical coverage of the February eroded the credibility of the king’s media control decree but it government three years ago. But a First royal takeover by its sister election announcement. z appears to be having the opposite landmark Supreme Court decision newspapers. effect. in 2002 won FM stations the right But the crackdown has united After the heavy-handed to broadcast news. the media like nothing before. Breaking news midnight break-in on Kantipur FM Journalists and civil society Journalists and activists camped The Supreme Court late Thursday last Friday, the government gave members say it’s the sneaky way outside Kantipur FM on Thursday issued a stay order banning any the station a 24-hour ultimatum to the edict was announced on the as the government’s 4:30 PM government action against Kantipur stop broadcasting news. -

Nepalese Translation Volume 1, September 2017 Nepalese Translation

Nepalese Translation Volume 1, September 2017 Nepalese Translation Volume 1,September2017 Volume cg'jfbs ;dfh g]kfn Society of Translators Nepal Nepalese Translation Volume 1 September 2017 Editors Basanta Thapa Bal Ram Adhikari Office bearers for 2016-2018 President Victor Pradhan Vice-president Bal Ram Adhikari General Secretary Bhim Narayan Regmi Secretary Prem Prasad Poudel Treasurer Karuna Nepal Member Shekhar Kharel Member Richa Sharma Member Bimal Khanal Member Sakun Kumar Joshi Immediate Past President Basanta Thapa Editors Basanta Thapa Bal Ram Adhikari Nepalese Translation is a journal published by Society of Translators Nepal (STN). STN publishes peer reviewed articles related to the scientific study on translation, especially from Nepal. The views expressed therein are not necessarily shared by the committee on publications. Published by: Society of Translators Nepal Kamalpokhari, Kathmandu Nepal Copies: 300 © Society of Translators Nepal ISSN: 2594-3200 Price: NC 250/- (Nepal) US$ 5/- EDITORIAL strategies the practitioners have followed to Translation is an everyday phenomenon in the overcome them. The authors are on the way to multilingual land of Nepal, where as many as 123 theorizing the practice. Nepali translation is languages are found to be in use. It is through desperately waiting for such articles so that translation, in its multifarious guises, that people diverse translation experiences can be adequately speaking different languages and their literatures theorized. The survey-based articles present a are connected. Historically, translation in general bird's eye view of translation tradition in the is as old as the Nepali language itself and older languages such as Nepali and Tamang. than its literature. -

Trekking Trails in Nepal

Trek, Bike and Raft EXPLORING THE TOURISM POSSIBILITIES OF DOLPA THE RUBY VALLey TREK GANESH HIMAL REGION DiscoveringTAAN Tourism Destinations & Trekking Trails in Nepal LOWER MANASLU ECO TREK- GORKHA LUMBA - SUMBA PASS KANCHENJUNGA & MAKALU www.taan.org.np DiscoveringTAAN Tourism Destinations & Trekking Trails in Nepal © All rights reserved: Trekking Agencies' Association of Nepal- TAAN- 2012 All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under Copyright Laws of the Nepal, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the TAAN. Any enquiries should be directed to TAAN, [email protected] Trekking Agencies' Association of Nepal (TAAN) P.O. Box : 3612 Maligaun Ganeshthan, Kathmandu Tel. : 977-1-4427473, 4440920, 4440921 Fax : 977-1-4419245 Email : [email protected] Price: Organizational NRs. 500, Individual NRs. 300. Publication Coordinator: Amber Tamang Designed Processed by: PrintComm 42244148, Kathmandu Printed in Nepal Discovering Tourism Destinations & Trekking Trails in Nepal 5 TAAN STRENGTHENING THE TREKKING TOURISM INDUSTRY am highly privileged to offer you this I book, which is a product of very hard work and dedication of the team of TAAN. This book, “TAAN- Discovering Tourism Destinations and Trekking Trails in Nepal”, is a very important book in the tourism industry of Nepal. There are dozens of trekking trails discovered and described in detail with day-to –day itineraries. Lumba-Sumba Pass Taplejung, Eco-cultural trails in Gorkha, high altitude treks and cultural book possible in time working days treks in Dhading Ganesh Himal region, and nights. and incredible, hidden treasures trekking in Dolpa district have been I remember all the individuals involved studied by different teams of experts in this process. -

Member Number Full Name Gender Membership Type M1718-195

Member Number Full Name Gender Membership Type M1718-195 Aakriti Dhakal Female General M1718-401 Aaradhana Devkota Nepal Female Student M1718-623 Aashika Upreti Ganywali Female Student M1718-499 Aashish Kandel Male Student M1718-498 Aashish Karki Male General M1718-482 Aayush Sapkota Male Student M1718-596 Abhinit Singh Male General M1718-241 ABINA GURUNG Female General M1718-274 Achyut Acharya Male General M1718-69 Adesh Sharma Male General M1718-130 Aditya Shrestha Male Student M1718-313 Akriti Chitrakar Female Student M1718-556 Akriti Ghimire Female General M1718-258 Aliz Karki Male Student M1718-307 Aliza Karki Female General M1718-20 Alok Kharel Male General M1718-296 Ambika Bhattarai Female General M1718-305 Ambika Sharma Female Student M1718-448 Ambika Tamang Female Student M1718-557 Ambika Adhikari Female General M1718-361 Ambika Bhusal adhikari Female Student M1718-18 Amit Parajuli Male General M1718-437 Amit Thapa Male Student M1718-275 Amita Shrestha Female General M1718-434 Amol Kattel Male Student M1718-618 Amrit Gyanwaly Male General M1718-24 Amrit Adhikari Male Student M1718-527 Amrita Gautam Female General M1718-370 Ananta Ghimire Female General M1718-555 Angir Babu Dahal Male General M1718-301 Angira Himadri Female Student M1718-34 Anil Basnet Male Current Team M1718-479 Anil Shrestha Male Student M1718-439 Anita Thapa Adhikari Female General M1718-229 Anita Pokharel Baskota Female General M1718-335 Anjan Paudel Male Student M1718-13 Anjana Pant Baral Female Current Team M1718-523 Anjana Poudel Female General M1718-174