The Surgical Plane for Lingual Tonsillectomy: an Anatomic Study Eugene L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Te2, Part Iii

TERMINOLOGIA EMBRYOLOGICA Second Edition International Embryological Terminology FIPAT The Federative International Programme for Anatomical Terminology A programme of the International Federation of Associations of Anatomists (IFAA) TE2, PART III Contents Caput V: Organogenesis Chapter 5: Organogenesis (continued) Systema respiratorium Respiratory system Systema urinarium Urinary system Systemata genitalia Genital systems Coeloma Coelom Glandulae endocrinae Endocrine glands Systema cardiovasculare Cardiovascular system Systema lymphoideum Lymphoid system Bibliographic Reference Citation: FIPAT. Terminologia Embryologica. 2nd ed. FIPAT.library.dal.ca. Federative International Programme for Anatomical Terminology, February 2017 Published pending approval by the General Assembly at the next Congress of IFAA (2019) Creative Commons License: The publication of Terminologia Embryologica is under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0) license The individual terms in this terminology are within the public domain. Statements about terms being part of this international standard terminology should use the above bibliographic reference to cite this terminology. The unaltered PDF files of this terminology may be freely copied and distributed by users. IFAA member societies are authorized to publish translations of this terminology. Authors of other works that might be considered derivative should write to the Chair of FIPAT for permission to publish a derivative work. Caput V: ORGANOGENESIS Chapter 5: ORGANOGENESIS -

Oral Cavity Histology Histology > Digestive System > Digestive System

Oral Cavity Histology Histology > Digestive System > Digestive System Oral Cavity LINGUAL PAPILLAE OF THE TONGUE Lingual papillae cover 2/3rds of its anterior surface; lingual tonsils cover its posterior surface. There are three types of lingual papillae: - Filiform, fungiform, and circumvallate; a 4th type, called foliate papillae, are rudimentary in humans. - Surface comprises stratified squamous epithelia - Core comprises lamina propria (connective tissue and vasculature) - Skeletal muscle lies deep to submucosa; skeletal muscle fibers run in multiple directions, allowing the tongue to move freely. - Taste buds lie within furrows or clefts between papillae; each taste bud comprises precursor, immature, and mature taste receptor cells and opens to the furrow via a taste pore. Distinguishing Features: Filiform papillae • Most numerous papillae • Their role is to provide a rough surface that aids in chewing via their keratinized, stratified squamous epithelia, which forms characteristic spikes. • They do not have taste buds. Fungiform papillae • "Fungi" refers to its rounded, mushroom-like surface, which is covered by stratified squamous epithelium. Circumvallate papillae • Are also rounded, but much larger and more bulbous. • On either side of the circumvallate papillae are wide clefts, aka, furrows or trenches; though not visible in our sample, serous Ebner's glands open into these spaces. DENTITION Comprise layers of calcified tissues surrounding a cavity that houses neurovascular structures. Key Features Regions 1 / 3 • The crown, which lies above the gums • The neck, the constricted area • The root, which lies within the alveoli (aka, sockets) of the jaw bones. • Pulp cavity lies in the center of the tooth, and extends into the root as the root canal. -

DHE121 Lesson Objectives

Instructional Objectives for DHE121 Identify the following anatomical structures and terms: Parotid Papilla Canine Eminence Parotid Duct or Stenson’s Duct Primary Teeth Maxilla Permanent Teeth Mandible Anterior Teeth Maxillary Sinuses or Paranasal Sinuses Posterior Teeth Alveolar Process or Bone Incisors Maxillary or Mandibular Vestibule Canines Buccal, Labial, and Alveolar Mucosa Premolars Vestibular Fornix Molars Mucobuccal Fold Exostoses Labial Frenum Pulp Cavity Alveolus Torus or Tori Periodontal Ligament (PDL) Gingiva Crown of a Tooth Attached Gingiva Root of a Tooth Alveolar Mucosa Enamel Mucogingival Junction Dentin Marginal Gingiva Cementum Gingival Sulcu Maxillary or Mandibular Tuberosity Interdental Gingiva or Papilla Fordyce Spots Fauces Linea Alba Anterior and Posterior Tonsillar Pillar Retromolar Pad Palatine Tonsils Palate Hard and Soft Median Palatine Raphe Incisive Papilla Palatine Rugae Uvula of the Palate Pterygomandibular Fold or Raphe Base of the Tongue Body of the Tongue Apex of the Tongue Lingual Papillae Dorsal Surface of the Tongue Median Lingual Sulcus of the Tongue Filiform Lingual Papillae Fungiform Lingual Papillae Sulcus Terminalis of the Tongue Foramen Cecum Circumvallate Lingual Papillae Lingual Tonsil Lateral Surface of the Tongue Foliate Lingual Papillae Ventral Surface of the Tongue Plicae Fimbriata Lingual Frenum Sublingual Fold Sublingual Salivary Gland Sublingual Caruncle Submandibular Duct (Wharton’s Duct) Sublingual Duct (Bartholin’s Duct) Laryngopharynx Nasopharynx Oropharynx Facial or Labial Anterior Buccal Posterior Palatal Frenum Lingual Dorsal Vestibules Oral Mucosa or Mucous Membrane Mastication DHE121 ORAL CAVITY 1. Describe the boundaries of the oral cavity. 2. Cite the two parts of the oral cavity. 3. Define: vestibule oral cavity proper mucobuccal fold frenum alveolar mucosa gingiva exotoses palatine tori (torus palatinis) mandibular tori (torus mandibularis) 4. -

Adult Tonsillectomy and / Or Sleep Apnea Surgery

2201 Glenwood Ave., Joliet, IL 60435 ENT SURGICAL CONSULTANTS (815) 725-1191, (815) 725-1248 fax (815) 929-2262 Answer Service Thomas K. Kron, MD, FACS 1890 Silver Cross Blvd, Pavilion A, Suite 435, New Lenox, IL 60451 Michael G. Gartlan, MD, FAAP, FACS (815) 717-8768 Rajeev H. Mehta, MD, FACS 900 W. Route 6, Suite 960, Morris, IL 60450 Scott W. DiVenere, MD Sung J. Chung, MD (815) 941-1972 Ankit M. Patel, MD www.entsurgicalillinois.com ADULT TONSILLECTOMY AND/OR SLEEP APNEA SURGERY (1/16) There is a large ring of lymphoid tissue throughout the throat that provides an immune function in the upper respiratory tract during childhood. The largest components of this ring include a pair of palatine tonsils that can be seen through the mouth on each side and the pharyngeal tonsil, commonly referred to as the adenoid, which is located in the upper throat behind the nose. All these tonsil tissues and the lymph nodes in the neck work together to “catch” and trap incoming infections. Unfortunately, the tonsil and adenoid may become the source of infection itself like a plugged filter Ear, Nose & Throat Diseases or they can become so Otolaryngologylarge as to obstruct-Head the airway. & Neck Surgery Facial Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery Usually tonsils and adenoidsThyroid peak inand size P arathyroidby 8 years of Surgery age, then begin to gradually shrink and atrophy by 12 years of age. By this age near complete facial and dental growth has occurred.Pediatric Adolescents Otolaryngology and adults with persistently enlarged tonsils are considered abnormal and usually result from chronic bacteria colonization of the tonsil crypts. -

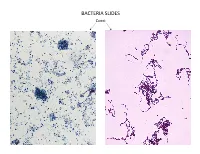

Bacteria Slides

BACTERIA SLIDES Cocci Bacillus BACTERIA SLIDES _______________ __ BACTERIA SLIDES Spirilla BACTERIA SLIDES ___________________ _____ BACTERIA SLIDES Bacillus BACTERIA SLIDES ________________ _ LUNG SLIDE Bronchiole Lumen Alveolar Sac Alveoli Alveolar Duct LUNG SLIDE SAGITTAL SECTION OF HUMAN HEAD MODEL Superior Concha Auditory Tube Middle Concha Opening Inferior Concha Nasal Cavity Internal Nare External Nare Hard Palate Pharyngeal Oral Cavity Tonsils Tongue Nasopharynx Soft Palate Oropharynx Uvula Laryngopharynx Palatine Tonsils Lingual Tonsils Epiglottis False Vocal Cords True Vocal Cords Esophagus Thyroid Cartilage Trachea Cricoid Cartilage SAGITTAL SECTION OF HUMAN HEAD MODEL LARYNX MODEL Side View Anterior View Hyoid Bone Superior Horn Thyroid Cartilage Inferior Horn Thyroid Gland Cricoid Cartilage Trachea Tracheal Rings LARYNX MODEL Posterior View Epiglottis Hyoid Bone Vocal Cords Epiglottis Corniculate Cartilage Arytenoid Cartilage Cricoid Cartilage Thyroid Gland Parathyroid Glands LARYNX MODEL Side View Anterior View ____________ _ ____________ _______ ______________ _____ _____________ ____________________ _____ ______________ _____ _________ _________ ____________ _______ LARYNX MODEL Posterior View HUMAN HEART & LUNGS MODEL Larynx Tracheal Rings Found on the Trachea Left Superior Lobe Left Inferior Lobe Heart Right Superior Lobe Right Middle Lobe Right Inferior Lobe Diaphragm HUMAN HEART & LUNGS MODEL Hilum (curvature where blood vessels enter lungs) Carina Pulmonary Arteries (Blue) Pulmonary Veins (Red) Bronchioles Apex (points -

Eponyms in Head and Neck Anatomy and Radiology

Pictorial Essay Eponyms in Head and Neck Anatomy and Radiology Fernando Martín Ferraro1*, Hernán Chaves2*, Federico Martín Olivera Plata3,4*, Luis Ariel Miquelini1,3*, Suresh K. Mukherji5 1 Imaging Service, Hospital Británico, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina 2 Imaging Department, Dr. Raúl Carrea Institute for Neurological Research (FLENI), Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina 3Imaging Service, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina 4 Magnetic Resonance and Computed Tomography Service, Centro Médico Deragopyan, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina 5 Radiology Department, Michigan State University, East Lansing, USA Abstract The use of eponyms in medical language is frequent. While it is commonly thought that eponyms are on their way to extinction, this is not entirely true. There is dissent between those who believe that their use should be abandoned and those who advocate that eponyms make unmemorable terms memorable, convey complex concepts and promote an interest in the history of medicine. We feel part of this second group, and our intention is to make a review of eight eponyms linked to head and neck anatomy and radiology. We believe that this approach can be useful for the education of medical students, residents and diagnostic imaging specialists. Keywords Radiology; Eponyms; Anatomy; Head and neck; History of medicine Introduction for which they are known. Eponyms are illustrated by figures of dissections, radiological images and pictures. We believe When we look up the word eponym in Spanish (epónimo) that this approach can be useful for the education of medical in the dictionary of the Spanish Royal Academy, we find the students, residents and diagnostic imaging specialists. -

Some Observations on Tonsils

SOME OBSERVATIONS ON TONSILS By T. A. MACGIBBON, B.A. B. Sc. N.Z. M.B. Ch. B. Edin. F.R.C.S. Edin. Christchurch, N.Z. June 1st, 1918. 1 SOME OBSERVATIONS ON TONSILS I have chosen this subject for many reasons: (1): Enlarged and diseased tonsils are common in this district: The causes are, probably, the flat and low-lying country, the underlying surface and artesian water, the constancy and variability of the winds, and the proximity to the sea. Our climate is not unlike that of the British Isles on the whole, though we are ten degrees nearer to the equator. We have a heavy vapour density and fogs are common. Hot winds from the N.W. will be followed by cold S.W. winds and rain, or the biting East winds with or without a drizzle. (2) Because so many operations are done upon the tonsils in this country, and particularly in this town. For my paper I have had to rely on the "British Journal of Laryngology," the "American Laryngoscope," the "British Medical Journal," about half a dozen standard works on Ear, Nose and Throat, and some excerpts from Continental works sent to me by the Librarian of the Royal Medical Society. Brieger's and other Continental works I have been unable to procure. My work as throat surgeon at the Christchurch Hospital has afforded me a fairly large experience, but I regret that I have been unable to get any pathological research work done on the tonsils I have removed. However, I would like to draw certain conclusions from my experience, and from my reading, which, may offer something interesting and profitable to the profession. -

Chapter 1 Oral Structures and Tissues Arthur R

Chapter 1 Oral Structures and Tissues Arthur R. Hand1 and Marion E. Frank2 1 Department of Craniofacial Sciences and Cell Biology , School of Dental Medicine, University of Connecticut 2 Department of Oral Health and Diagnostic Sciences , University of Connecticut The oral cavity and its component cells, tissues, and structures the lips and the mucosa lining the inside of the lips, and extends constitute a unique and complex organ system and environment. posteriorly to the palatoglossal folds or arch . Beyond the palato- Of necessity, we study its various parts individually, but the glossal folds are the palatopharyngeal folds and the beginning health and function of the components of the oral cavity depend of the oropharynx , where the digestive and respiratory tracts upon and influence one another. Importantly, the oral cavity come together. The palatine tonsils are located in the tonsillar relies on as well as influences the health and function of the fauces between the palatoglossal and palatopharyngeal folds. entire body. The lymphoid tissue of the palatine tonsils, along with that of the The oral cavity is the gateway to the body, and most of the pharyngeal tonsil ( adenoids ) and the lingual tonsils , guards the substances that enter our bodies do so through the oral cavity. It entrance to the oropharynx. Anteriorly, the respiratory tract is exposed to the physical insults of mastication, hard objects and (nasal cavity) is separated from the oral cavity by the hard palate , various food substances, and extremes of temperature. A variety and posteriorly by the soft palate . The hard palate has an arch-like of chemicals, including those present in foods and drinks and shape that varies in width and height among individuals. -

The Pseudolesions of the Oral Mucosa: Differential Diagnosis and Related Systemic Conditions

applied sciences Review The Pseudolesions of the Oral Mucosa: Differential Diagnosis and Related Systemic Conditions Fedora della Vella 1,* , Dorina Lauritano 2 , Carlo Lajolo 3 , Alberta Lucchese 4, Dario Di Stasio 4 , Maria Contaldo 4 , Rosario Serpico 4 and Massimo Petruzzi 1,* 1 Interdisciplinary Department of Medicine, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70124 Bari, Italy 2 School of Medicine and Surgery, University of Milano-Bicocca, 20900 Monza, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Head and Neck, Oral Surgery and Implantology Unit, University Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, 00168 Rome, Italy; [email protected] 4 Multidisciplinary Department of Medical-Surgical and Dental Specialties, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, 80138 Naples, Italy; [email protected] (A.L.); [email protected] (D.D.S.); [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (R.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (F.d.V.); [email protected] (M.P.); Tel.: +39-0805478388 (F.d.V.) Received: 7 May 2019; Accepted: 10 June 2019; Published: 13 June 2019 Abstract: Pseudolesions are defined as physiological or paraphysiological changes of the oral normal anatomy that can easily be misdiagnosed for pathological conditions such as potentially malignant lesions, infective and immune diseases, or neoplasms. Pseudolesions do not require treatment and a surgical or pharmacological approach can constitute an overtreatment indeed. This review aims to describe the most common pseudolesions of oral soft tissues, their possible differential diagnosis and eventual related systemic diseases or syndromes. The pseudolesions frequently observed in clinical practice and reported in literature include Fordyce granules, leukoedema, geographic tongue, fissured tongue, sublingual varices, lingual fimbriae, vallate papillae, white and black hairy tongue, Steno’s duct hypertrophy, lingual tonsil, white sponge nevus, racial gingival pigmentation, lingual thyroid, and eruptive cyst. -

26 April 2010 TE Prepublication Page 1 Nomina Generalia General Terms

26 April 2010 TE PrePublication Page 1 Nomina generalia General terms E1.0.0.0.0.0.1 Modus reproductionis Reproductive mode E1.0.0.0.0.0.2 Reproductio sexualis Sexual reproduction E1.0.0.0.0.0.3 Viviparitas Viviparity E1.0.0.0.0.0.4 Heterogamia Heterogamy E1.0.0.0.0.0.5 Endogamia Endogamy E1.0.0.0.0.0.6 Sequentia reproductionis Reproductive sequence E1.0.0.0.0.0.7 Ovulatio Ovulation E1.0.0.0.0.0.8 Erectio Erection E1.0.0.0.0.0.9 Coitus Coitus; Sexual intercourse E1.0.0.0.0.0.10 Ejaculatio1 Ejaculation E1.0.0.0.0.0.11 Emissio Emission E1.0.0.0.0.0.12 Ejaculatio vera Ejaculation proper E1.0.0.0.0.0.13 Semen Semen; Ejaculate E1.0.0.0.0.0.14 Inseminatio Insemination E1.0.0.0.0.0.15 Fertilisatio Fertilization E1.0.0.0.0.0.16 Fecundatio Fecundation; Impregnation E1.0.0.0.0.0.17 Superfecundatio Superfecundation E1.0.0.0.0.0.18 Superimpregnatio Superimpregnation E1.0.0.0.0.0.19 Superfetatio Superfetation E1.0.0.0.0.0.20 Ontogenesis Ontogeny E1.0.0.0.0.0.21 Ontogenesis praenatalis Prenatal ontogeny E1.0.0.0.0.0.22 Tempus praenatale; Tempus gestationis Prenatal period; Gestation period E1.0.0.0.0.0.23 Vita praenatalis Prenatal life E1.0.0.0.0.0.24 Vita intrauterina Intra-uterine life E1.0.0.0.0.0.25 Embryogenesis2 Embryogenesis; Embryogeny E1.0.0.0.0.0.26 Fetogenesis3 Fetogenesis E1.0.0.0.0.0.27 Tempus natale Birth period E1.0.0.0.0.0.28 Ontogenesis postnatalis Postnatal ontogeny E1.0.0.0.0.0.29 Vita postnatalis Postnatal life E1.0.1.0.0.0.1 Mensurae embryonicae et fetales4 Embryonic and fetal measurements E1.0.1.0.0.0.2 Aetas a fecundatione5 Fertilization -

Neurotrophins and Their Receptors in Human Lingual Tonsil: an Immunohistochemical Analysis

1201-1206 10/10/08 13:52 Page 1201 ONCOLOGY REPORTS 20: 1201-1206, 2008 Neurotrophins and their receptors in human lingual tonsil: An immunohistochemical analysis MARCO ARTICO1, ELENA BRONZETTI2, LAURA M. FELICI2, VALENTINA ALICINO1, BRUNELLA IONTA1, BENEDETTO BRONZETTI3, GIUSEPPE MAGLIULO1, CLAUDIA GRANDE2, LORIS ZAMAI4, GUIDO PASQUANTONIO5 and MARCO DE VINCENTIIS1 1Giorgio Ferreri Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Audiology, and Phoniatry, University of Rome ‘La Sapienza’, Piazzale A. Moro 5, I-00185 Rome; 2Department of Cardiovascular, Respiratory and Morphological Sciences, University of Rome ‘La Sapienza’, Via A. Borelli 50, I-00161 Rome; 3Nuovo Presidio Ospedaliero Cutroni-Zodda, Barcellona Pozzo di Gotto, Messina; 4Institute of Histology and Laboratory Analysis and Center of Cytometry and Cytomorphology, University of Urbino, Urbino; 5Department of Dental Sciences, University of Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy Received May 14, 2008; Accepted June 13, 2008 DOI: 10.3892/or_00000130 Abstract. Lymphoid organs are supplied by many nerve Introduction endings associated with different kinds of cells and macro- phages. The role of this innervation on the release of locally The nasopharyngeal tonsil (adenoids) and palatine and lingual active molecules is still unclear. Lingual tonsils belong to tonsils constitute the major part of Waldeyer's Ring, with the Waldeyer's Ring, in close association with palatine tonsils tubal tonsils and lateral pharyngeal bands as less prominent and nasopharyngeal (adenoids) tonsils, thus constituting part components. All parts of Waldeyer's Ring are located to of NALT (nasal-associated lymphoid tissue) together with perform regional immune functions because they are exposed the tubal tonsils and lateral pharyngeal bands. In this study, to both airborne and alimentary antigens. -

Assessment of Age-Related

Assessment of Age-Related Morphological and Functional Changes of Selected Structures of the Head and Neck by Computed Tomography, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, and Positron Emission Tomography Anton Mahne, MD, Ghassan El-Haddad, MD, Abass Alavi, MD, Mohamed Houseni, MD, Gul Moonis, MD, Andrew Mong, MD, Miguel Hernandez-Pampaloni, MD, PhD, and Drew A. Torigian, MD, MA The head and neck is a complex anatomical region that can be evaluated using many imaging modalities. It is important to discern normal structures from ones that are affected by disease and to study how these structures change in their morphological and functional properties with aging. Therefore, using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), we retrospec- tively evaluated volumes of the parotid glands, submandibular glands, thyroid gland, tongue, soft palate, and lingual tonsils in 64 subjects ages 13 to 81 years. Volume, attenuation (HU), and metabolic activity (maximum SUV) of the parotid, submandibular, and thyroid glands were assessed retrospectively using positron emission tomography/com- puted tomography (PET/CT) imaging in 35 subjects ages 10 to 76 years. Metabolic activity (maximum SUV) of the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands; tongue; adenoids; and tonsils (lingual and palatine) were evaluated retrospectively using PET imaging in 15 subjects ages 6 to 20 years. Metabolic volumetric products of the parotid, submandibular, and thyroid gland were calculated and analyzed with increasing age in subjects who underwent PET/CT imaging. Structures that exhibited statistically significant changes (P < 0.05) with increasing age included the submandibular glands, thyroid gland, soft palate, and adenoids. The CT volume of the submandibular glands increased with age, and the attenuation decreased with age with statistical significance.