Spring 2009 RURAL LIVING in ARIZONA Volume 3, Number 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evidence of Lingual-Luring by an Aquatic Snake

Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 34 No. 1 pp 67-74, 2000 Copyright 2000 Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Evidence of Lingual-luring by an Aquatic Snake HARTWELL H. WELSH, JR. AND AMY J. LIND Pacific Southwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 1700 Bayview Dr., Arcata, California 95521, USA. E-mail: hwelsh/[email protected] ABSTRACT.-We describe and quantify the components of an unusual snake behavior used to attract fish prey: lingual-luring. Our earlier research on the foraging behavior of the Pacific Coast aquatic garter snake (Thamnophis atratus) indicated that adults are active foragers, feeding primarily on aquatic Pacific giant salamanders (Dicamptodon tenebrosus) in streambed substrates. Juvenile snakes, however, use primarily ambush tactics to capture larval anurans and juvenile salmonids along stream margins, behaviors that include the lingual-luring described here. We found that lingual-luring differed from typical chemosensory tongue-flicking by the position of the snake, contact of the tongue with the water surface, and the length of time the tongue was extended. Luring snakes are in ambush position and extend and hold their tongues out rigid, with the tongue-tips quivering on the water surface, apparently mimicking insects in order to draw young fish within striking range. This behavior is a novel adaptation of the tongue-vomeronasal system by a visually-oriented predator. The luring of prey by snakes has been asso- luring function (Mushinsky, 1987; Ford and ciated primarily with the use of the tail, a be- Burghardt, 1993). However, Lillywhite and Hen- havior termed caudal luring (e.g., Neill, 1960; derson (1993) noted the occurrence of a pro- Greene and Campbell, 1972; Heatwole and Dav- longed extension of the tongue observed in vine ison, 1976; Jackson and Martin, 1980; Schuett et snakes (e.g., Kennedy, 1965; Henderson and al., 1984; Chizar et al., 1990). -

Bill Shape As a Generic Character in the Cardinals

BILL SHAPE AS A GENERIC CHARACTER IN THE CARDINALS WALTER J. BOCK ANY genera in birds and other animal groups have been based essentially M upon a single character. This character may be a single morphological feature, such as the presence or absence of the hallux, or it may be a complex of characters which are all closely correlated functionally, such as the bones, muscles, and ligaments of the jaw apparatus. The validity of many of these genera has been questioned in recent years with the general acceptance of the polytypic species concept and the increasing acknowledgment of the grouping service at low taxonomic levels provided by the genus. An example is the North American passerine genus Pyrrhuloxia, which is distinguished from Richmondena essentially on the basis of bill shape. The overall similarity of Pyrrhuloxia sinuata to the two species of Richmondena in morphology and in general life history (Gould, 1961) has led several recent authors to synony- mize Richmondena with Pyrrhuloxia. Other workers have maintained the validity of the generic separation, basing their decision largely on the dif- ference in bill shape. The object of this paper is to ascertain the importance of this difference as a taxonomic character and whether the difference if con- firmed is of generic significance. THE JAW APPARATUS Ridgway (19013624-625) described the bill of P. sinuata (see Figs. 1 and 2) as follows: “Bill very short, thick and deep, with culmen strongly convex and maxillary tomium deeply and angularly incised a little posterior to the middle -

Roadrunner Fact Sheet

Roadrunner Fact Sheet Common Name: Roadrunner Scientific Name: Geococcyx Californianus & Geococcyx Velox Wild Status: Not Threatened Habitat: Arid dessert and shrub Country: United States, Mexico, and Central America Shelter: These birds nest 1-3 meters off the ground in low trees, shrubs, or cactus Life Span: 8 years Size: 2 feet in length; 8-15 ounces Details The genus Geococcyx consists of two species of bird: the greater roadrunner and the lesser roadrunner. They live in the arid climates of Southwestern United States, Mexico, and Central America. Though these birds can fly, they spend most of their time running from shrub to shrub. Roadrunners spend the entirety of their day hunting prey and dodging predators. It's a tough life out there in the wild! These birds eat insects, small reptiles and mammals, arachnids, snails, other birds, eggs, fruit, and seeds. One thing that these birds do not have to worry about is drinking water. They intake enough moisture through their diet and are able to secrete any excess salt build-up through glands in their eyes. This adaptation is common in sea birds as their main source of hydration is the ocean. The fact that roadrunners have adapted this trait as well goes to show how well they are suited for their environment. A roadrunner will mate for life and will travel in pairs, guarding their territory from other roadrunners. When taking care of the nest, both male and female take turns incubating eggs and caring for their young. The young will leave the nest after a couple weeks and will then learn foraging techniques for a few days until they are left to fend for themselves. -

Caudal Distraction by Rat Snakes (Colubridae, Elaphe): a Novel Behavior Used When Capturing Mammalian Prey

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 59 Number 4 Article 8 10-15-1999 Caudal distraction by rat snakes (Colubridae, Elaphe): a novel behavior used when capturing mammalian prey Stephen J. Mullin University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Mullin, Stephen J. (1999) "Caudal distraction by rat snakes (Colubridae, Elaphe): a novel behavior used when capturing mammalian prey," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 59 : No. 4 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol59/iss4/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Great Ba....in Naturalist 59(4), ©1999, pp. 361....167 CAUDAL DISTRACTION BY RAT SNAKES (COLUBHIDAE, ELAPHE): A NOVEL BEHAVIOR USED WHEN CAPTURING MAMMALIAN PREY Stephen]. Mullin1 AJ3S11UCT.--el.mthtl movement in snakes trulY serve ei.ther a pl'Cdatory (e.g., caudal luring) or defensive (e.g., rattling, aposem,ttism) fUllction, I descliho n new behavioral pattern of tai.l movement in snakes. Gray rat snakl.'$ (Elaphe OhSO!etd spiloid.es) fi)raging on ~ma11 mmnmnls (Mus d01ne~·ticus) Inoved. their tails in un erratic, whiplike fashion uIter detecting prey in their vidnity. The thrashing movement in the horizontal plfme was audibly and visually obviolls, resulting in dis placement of leaf litter around the hlil. All subjects displayed the behavior, hilt not in all foraging episodes. -

2007 Australasian Society for the Study of Animal Behaviour & the International Union for the Study of Social Insects (Australian Chapter)

ASSAB 2007 AUSTRALASIAN SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR & THE INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR THE STUDY OF SOCIAL INSECTS (AUSTRALIAN CHAPTER) 12-15 April 2007 The Australian National University Canberra Venue Robertson Lecture Theatre Research School of Biological Sciences Building 46E Hosted by the Research School of Biological Sciences 2 Sponsored by the ARC Centre of Excellence in Vision Science (ACEVS) http://www.vision.edu.au/ LOCAL HOSTS: JOCHEN ZEIL Visual Sciences, Research School of Biological Sciences The Australian National University AJAY NARENDRA Visual Sciences, Research School of Biological Sciences The Australian National University ROB HEINSOHN Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies The Australian National University JAN HEMMI Visual Sciences, Research School of Biological Sciences The Australian National University RICHARD PETERS Visual Sciences, Research School of Biological Sciences The Australian National University WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO THE ASSAB TREASURER, XIMENA NELSON & THE ASSAB PRESIDENT PHIL TAYLOR FOR THEIR SUPPORT Thursday, 12 April Friday, 13 April Saturday, 14 April Sunday, 15 April 8:00 Plenary Lecture Tinbergen Centenary Lecture IUSSI Lecture 9:00 ASSAB 2007 Barbara Webb Chris Evans & Jochen Zeil Ryszard Maleszka 12 - 15 April 2007 09:30 09:30 09:30 Session 3: RSBS Session 8: Session 12: 10:00 SENSORY SYSTEMS & SOCIAL INSECTS I COMMUNICATION I HOMING & NAVIGATION Tea/CoffeeTea/Coffee Break Break Tea/Coffee Break 11:00 Session 9: FORAGING, COMPETITION & Session 4: LIFE HISTORIES I Session 13: -

Variability and Distribution of the Golden-Headed Weevil Compsus Auricephalus (Say) (Curculionidae: Entiminae: Eustylini)

Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e55474 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.8.e55474 Single Taxon Treatment Variability and distribution of the golden-headed weevil Compsus auricephalus (Say) (Curculionidae: Entiminae: Eustylini) Jennifer C. Girón‡, M. Lourdes Chamorro§ ‡ Natural Science Research Laboratory, Museum of Texas Tech University, Lubbock, United States of America § Systematic Entomology Laboratory, ARS, USDA, c/o National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, United States of America Corresponding author: Jennifer C. Girón ([email protected]) Academic editor: Li Ren Received: 15 Jun 2020 | Accepted: 03 Jul 2020 | Published: 09 Jul 2020 Citation: Girón JC, Chamorro ML (2020) Variability and distribution of the golden-headed weevil Compsus auricephalus (Say) (Curculionidae: Entiminae: Eustylini). Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e55474. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.8.e55474 Abstract Background The golden-headed weevil Compsus auricephalus is a native and fairly widespread species across the southern U.S.A. extending through Central America south to Panama. There are two recognised morphotypes of the species: the typical green form, with pink to cupreous head and part of the legs and the uniformly white to pale brown form. There are other Central and South American species of Compsus and related genera of similar appearance that make it challenging to provide accurate identifications of introduced species at ports of entry. New information Here, we re-describe the species, provide images of the habitus, miscellaneous morphological structures and male and female genitalia. We discuss the morphological variation of Compsus auricephalus across its distributional range, by revising and updating This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC0 Public Domain Dedication. -

Flora and Fauna List.Xlsx

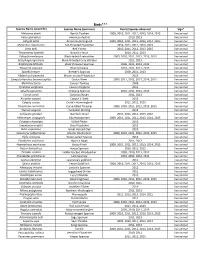

Birds*** Species Name (scientific) Species Name (common) Year(s) Species observed Sign* Melozone aberti Abert's Towhee 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Falco sparverius American Kestrel 2010, 2013 live animal Calypte anna Anna's Hummingbird 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Myiarchus cinerascens Ash‐throated Flycatcher 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Vireo bellii Bell's Vireo 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Thryomanes bewickii Bewick's Wren 2010, 2011, 2013 live animal Polioptila melanura Black‐tailed Gnatcatcher 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Setophaga nigrescens Black‐throated Gray Warbler 2011, 2013 live animal Amphispiza bilineata Black‐throated Sparrow 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Passerina caerulea Blue Grosbeak 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Spizella breweri Brewer's Sparrow 2009, 2011, 2013 live animal Myiarchus tryannulus Brown‐crested Flycatcher 2013 live animal Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus Cactus Wren 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Melozone fusca Canyon Towhee 2009 live animal Tyrannus vociferans Cassin's Kingbird 2011 live animal Spizella passerina Chipping Sparrow 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Corvus corax Common Raven 2011, 2013 live animal Accipiter cooperii Cooper's Hawk 2013 live animal Calypte costae Costa's Hummingbird 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Toxostoma curvirostre Curve‐billed Thrasher 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Sturnus vulgaris European Starling 2012 live animal Callipepla gambelii Gambel's -

Status and Occurrence of Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis Cardinalis) in British Columbia

Status and Occurrence of Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) in British Columbia. By Rick Toochin and Don Cecile. Submitted: April 15, 2018. Introduction and Distribution The Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) is a charismatic passerine found throughout eastern Canada, the eastern United States, throughout Mexico, Belize and the Petén part of northern Guatemala (Halkin and Linville 1999, Howell and Webb 2010). This species is a year round resident throughout its range, but is slowly expanding its range northward and westward across North America (Halkin and Linville 1999). Nearly 90% of banded individuals that were found dead came from same 10-minute block of latitude and longitude where they were initially banded, and those found dead at greater distances show no directional pattern in movements (Dow and Scott 1971). Reports of possible migration may be accounted for by dispersing juveniles (Halkin and Linville 1999). There is no known record of a breeding bird recovered at great distance in the following winter (Halkin and Linville 1999). The Northern Cardinal is found in areas with shrubs, small trees, including forest edges and interior, shrubby areas in logged and second-growth forests, marsh edges, grasslands with shrubs, successional fields, hedgerows in agricultural fields, and plantings around buildings (Dow 1969a, Dow 1969b, Emlen 1972a). In general, this species’ breeding range has expanded northward since the mid- 1800s, owing to 3 probable factors: warmer climate, resulting in lesser snow depth and greater winter foraging opportunities; human encroachment into forested areas, increasing suitable edge habitat; and establishment of winter feeding stations, increasing food availability (Halkin and Linville 1999). There are 18 subspecies of the Northern Cardinal; most are found in Mexico (Clements et al. -

Bird List of San Bernardino Ranch in Agua Prieta, Sonora, Mexico

Bird List of San Bernardino Ranch in Agua Prieta, Sonora, Mexico Melinda Cárdenas-García and Mónica C. Olguín-Villa Universidad de Sonora, Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico Abstract—Interest and investigation of birds has been increasing over the last decades due to the loss of their habitats, and declination and fragmentation of their populations. San Bernardino Ranch is located in the desert grassland region of northeastern Sonora, México. Over the last decade, restoration efforts have tried to address the effects of long deteriorating economic activities, like agriculture and livestock, that used to take place there. The generation of annual lists of the wildlife (flora and fauna) will be important information as we monitor the progress of restoration of this area. As part of our professional training, during the summer and winter (2011-2012) a taxonomic list of bird species of the ranch was made. During this season, a total of 85 species and 65 genera, distributed over 30 families were found. We found that five species are on a risk category in NOM-059-ECOL-2010 and 76 species are included in the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It will be important to continue this type of study in places that are at- tempting restoration and conservation techniques. We have observed a huge change, because of restoration activities, in the lands in the San Bernardino Ranch. Introduction migratory (Villaseñor-Gómez et al., 2010). Twenty-eight of those species are considered at risk on a global scale, and are included in Birds represent one of the most remarkable elements of our en- the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature vironment, because they’re easy to observe and it’s possible to find (IUCN). -

Nelson Et Al No Highlight-1 Edit Changes

1 Receiver psychology and the design of the deceptive caudal luring signal of the death 2 adder 3 Ximena J. Nelsona,b* Daniel T. Garnettc, 1 Christopher S. Evansb, 2 4 5 aSchool of Biological Sciences, University of Canterbury 6 bCentre for the Integrative Study of Animal Behaviour, Macquarie University 7 cDepartment of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University 8 Received 6 July 2009 9 Initial acceptance 4 September 2009 10 Final acceptance 30 November 2009 11 MS. number: 09-00453R 12 13 *Correspondence: X. J. Nelson, School of Biological Sciences, University of Canterbury, 14 Private Bag 4800, Christchurch, New Zealand. 15 E-mail address: [email protected] (X. J. Nelson). 16 1D. T. Garnett is at the Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, 17 NSW 2109 Australia. 18 2C. S. Evans is at the Centre for the Integrative Study of Animal Behaviour, Macquarie 19 University, Sydney, NSW 2109 Australia. 20 1 21 Signal design can reflect the sensory properties of receivers. The death adder, Acanthophis 22 antarcticus, attracts prey by wriggling the distal portion of its tail (caudal luring). To 23 understand the design of this deceptive signal, we explored perceptual processes in a 24 representative prey species: the Jacky dragon, Amphibolurus muricatus. We used 3D 25 animations of fast and slow death adder luring movements against different backgrounds, to 26 test the hypothesis that caudal luring mimics salient aspects of invertebrate prey. Moving 27 stimuli elicited predatory responses, especially against a conspicuous background. To identify 28 putative models for caudal luring, we used an optic flow algorithm to extract velocity values 29 from video sequences of 61 moving invertebrates caught in lizard territories, and compared 30 these to the velocity values of death adder movements. -

Comments on the Status of Revived Old Names for Some North American Birds

The Auk 112(3):633-648, 1995 COMMENTS ON THE STATUS OF REVIVED OLD NAMES FOR SOME NORTH AMERICAN BIRDS RICHARD C. BANKS AND M. RALPH BROWNING NationalBiological Service, National Museum of Natural History, MRC 111, Washington,D.C. 20560, USA AnSTRACT.--Wediscuss 44 instancesof the use of generic, specific,or subspecificnames that differ from those generally in use for North American (sensuAOU 1957) birds. These namesare generally older than the namespresently used and have been revived on the basis of priority. We examine the basisfor the proposedchanges and make recommendationsas to which namesshould properlybe usedin an effort to promotenomenclatural stability in accordancewith the InternationalCode of ZoologicalNomenclature. Received 22 February1994, accepted5 September1994. THEINTERNATIONAL COMMISSION of Zoological su AmericanOrnithologists' Union [AOU] 1957) Nomenclature (I.C.Z.N. 1985) promotesstabil- birds. ity in scientificnames of animals through the We do not discuss the use of old names that use of the InternationalCode of ZoologicalNo- are necessarilyrevived becausea taxon is di- menclature(hereinafter the Code). A primary vided into two or more taxa, unless there is an tenet of the Codeis the principle of priority, additional problem involved. Those situations which statesthat the earliestvalidly proposed are no less important, but require an analysis name for a genus or speciesshould be used, of validity of the basisof the "split," which is although some exceptionsare possible.There beyondthe scopeof this study.We do not dis- are, however, differencesof opinion about the cusschanges necessitated by decisionsof the validity and applicability of some early-pro- International Commissionon Zoological No- posednames. Furthermore, some sources of sci- menclature (hereinafter, the Commission) not- entific nameswere published before or after the ed by and incorporatedby the AOU (1973,1983) generally accepteddate of publication (Brown- unlessthe decisionhas been violated by an au- ing and Monroe 1991), a situation that can alter thor after 1973. -

Gila Monster Saguaro Cactus Roadrunner Coyote Elf Owl Mule

Gila Monster Saguaro Cactus Roadrunner Coyote Elf Owl Mule Deer Javelina Desert Tortoise Ocotillo Tarantula Bobcat Cholla Cactus Desert Toad Jackrabbit Prickly Pear Cactus Rattlesnake http:thefilesofmrse.com Bobcat Rattlesnake Desert Toad Tarantula Jackrabbit Cholla Cactus Ocotillo Gila Monster Prickly Pear Cactus Elf Owl Saguaro Cactus Mule Deer Coyote Javelina Desert Tortoise Roadrunner http:thefilesofmrse.com Saguaro Cactus Coyote Jackrabbit Javelina Desert Tortoise Ocotillo Elf Owl Rattlesnake Bobcat Cholla Cactus Prickly Pear Cactus Desert Toad Mule Deer Roadrunner Gila Monster Tarantula http:thefilesofmrse.com Desert Toad Desert Tortoise Saguaro Cactus Bobcat Jackrabbit Mule Deer Cholla Cactus Gila Monster Prickly Pear Cactus Elf Owl Tarantula Javelina Coyote Rattlesnake Roadrunner Ocotillo http:thefilesofmrse.com Javelina Gila Monster Roadrunner Ocotillo Rattlesnake Bobcat Prickly Pear Cactus Elf Owl Saguaro Cactus Tarantula Coyote Jackrabbit Desert Toad Desert Tortoise Mule Deer Cholla Cactus http:thefilesofmrse.com Jackrabbit Prickly Pear Cactus Rattlesnake Desert Tortoise Desert Toad Coyote Ocotillo Gila Monster Cholla Cactus Mule Deer Bobcat Javelina Roadrunner Tarantula Saguaro Cactus Elf Owl http:thefilesofmrse.com Coyote Mule Deer Desert Toad Saguaro Cactus Desert Tortoise Prickly Pear Cactus Gila Monster Roadrunner Javelina Elf Owl Tarantula Ocotillo Rattlesnake Jackrabbit Cholla Cactus Bobcat http:thefilesofmrse.com Tarantula Elf Owl Javelina Prickly Pear Cactus Desert Tortoise Saguaro Cactus Gila Monster Rattlesnake Bobcat