Status and Occurrence of Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis Cardinalis) in British Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Shape As a Generic Character in the Cardinals

BILL SHAPE AS A GENERIC CHARACTER IN THE CARDINALS WALTER J. BOCK ANY genera in birds and other animal groups have been based essentially M upon a single character. This character may be a single morphological feature, such as the presence or absence of the hallux, or it may be a complex of characters which are all closely correlated functionally, such as the bones, muscles, and ligaments of the jaw apparatus. The validity of many of these genera has been questioned in recent years with the general acceptance of the polytypic species concept and the increasing acknowledgment of the grouping service at low taxonomic levels provided by the genus. An example is the North American passerine genus Pyrrhuloxia, which is distinguished from Richmondena essentially on the basis of bill shape. The overall similarity of Pyrrhuloxia sinuata to the two species of Richmondena in morphology and in general life history (Gould, 1961) has led several recent authors to synony- mize Richmondena with Pyrrhuloxia. Other workers have maintained the validity of the generic separation, basing their decision largely on the dif- ference in bill shape. The object of this paper is to ascertain the importance of this difference as a taxonomic character and whether the difference if con- firmed is of generic significance. THE JAW APPARATUS Ridgway (19013624-625) described the bill of P. sinuata (see Figs. 1 and 2) as follows: “Bill very short, thick and deep, with culmen strongly convex and maxillary tomium deeply and angularly incised a little posterior to the middle -

The Northern Cardinal Margaret Murphy, Horticulture Educator and Regional Food Coordinator

Week of February 2, 2015 For Immediate Release The Northern Cardinal Margaret Murphy, Horticulture Educator and Regional Food Coordinator The northern cardinal is probably the most recognizable bird in the back yard – at least the male. He wears brilliant red plumage throughout the year. It is this amazing color that has made him the subject in many photographs and artists’ drawings, especially in winter and often on Christmas cards. Nothing is quite as cheery as seeing this holiday red bird sitting on a tree branch with a snowy scene in the background. But let’s not forget the female cardinal. While she lacks the bright red feathers, she does hold the distinction of being one of few female songbirds in North America who sing. She often does so while sitting on the nest. According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology All About Birds website, a mated pair of northern cardinals will share song phrases. Northern cardinals are found in our region throughout the year. They are common to back yards and are frequently heard, though not always seen, perched in the higher branches of trees or shrubs while singing. They nest in shrubs, thickets or sometimes in low areas of evergreens and build their nests in the forks of small branches hidden in the dense foliage. The female builds a cup-shaped nest made of twigs. She will crush the twigs with her beak and bend them around her while she turns in the nest. She then pushes the twigs into the cup shape with her feet. The nest is lined with finer materials such as grasses or hair. -

Northern Cardinal - Cardinalis Cardinalis

Northern Cardinal - Cardinalis cardinalis Photo credit: commons.wikimedia.com. Female in left photo, male in right photo. The Northern cardinal is easily distinguishable from other birds by their bright red color and prominent crest, the Northern Cardinal is a territorial songbird often found in gardens as well as around the Garden City Bird Sanctuary. They prefer nesting in shrubs and trees. Bird Statistics Description Scientific name- Cardinalis cardinalis Size and Shape- Mid-sized songbird with a Family- Cardinalidae short and stout beak, a long tail, and a crested Conservation Status- Least concern head Length- 8.3-9.1 in (21-23 cm) Color Pattern- Males are mostly bright red Wingspan- 9.8-12.2 in (25-31 cm) with darker red wings. Females are more Weight- 1.5-1.7 oz (42-48 g) grayish tinged with red. Both sexes have a reddish beak and black around the beak Egg Statistics Behavior- Often found foraging on or near the Color- Brownish or grayish white speckled with ground near shrubbery. Males are territorial dark brown and can be aggressive Nest- Bowl-shaped that consists of twigs, leaves, Song- Series of high-pitched chirps and grasses Habitat- Live in dense and brushy areas such Clutch size- 2-5 eggs as edges of woodlands, thickets, swamps, Number of broods- 1-2 overgrown fields, and gardens Length- 0.9-1.1 in (1.7-2 cm) Range- Year-round in northern and central Width- 0.7-0.8 in (1.7-2 cm) part of the US, parts of southern Canada, Incubation period- 11-13 days Mexico, and around the Gulf of Mexico Nestling period- 7-13 days Diet- Mostly grains, seeds, and fruits from bird feeders and the ground supplemented with Additional Information: insects such as grasshoppers and cicadas http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Northern_cardinal http://birds.audubon.org/birds/northern- cardinal Thanks to Crystal Chang for this bird data page. -

Determining the Dominant Bird Species Among the Northern

Determining the Dominant Bird Species among the Northern Cardinal, Dark- eyed Junco, Tufted Titmouse, and the American Goldfinch in Lonaconing, Maryland Bird Communication • Transmit information – Food – Mates – Attacks – Escapes – Territory – Identifications • Displays – Visual Displays – Vocal Displays Agonistic Behaviors • Behaviors used when two birds interact – Hostile – Cooperative • Threat Displays (TD) – Display wings and beak – Move towards – Attacks • Submissive Displays (SD) – Turn head and beak away – Move away – Flee Dominant Bird • Use more TDs • Assert status • Move without hesitation to feeders or perch • Rank higher • Reserve access to mates, space, and food • Take fewer risks • Survive longer Subordinate Birds • Use more SDs • Move tentatively • Attacked by dominants • Have less access food • Displaced by dominant birds • Move to new locations • Have higher risk of death Dominant Interactions • Intraspecies Interactions – Older dominate younger – Males dominate females – Larger dominate smaller • Interspecies Interactions – Larger dominate smaller – More dominant depending on brain chemistry Purpose of the Study Look at the interactions between four different species of birds (Northern Cardinal, Dark-eyed Junco, Tufted Titmouse, and American Goldfinch) to determine which species is the most dominate in these interactions. Northern Cardinal • Is the largest bird – 42-48 g – 21-23 cm • Is sexually dimorphic – Males red – Females brown with red tinges • Eats seeds and fruit • Flock with other cardinals in the winter Dark-eyed -

Winter Bird Highlights 2015, Is Brought to You by U.S

Winter Bird Highlights FROM PROJECT FEEDERWATCH 2014–15 FOCUS ON CITIZEN SCIENCE • VOLUME 11 Focus on Citizen Science is a publication highlight- FeederWatch welcomes new ing the contributions of citizen scientists. This is- sue, Winter Bird Highlights 2015, is brought to you by U.S. project assistant Project FeederWatch, a research and education proj- ect of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Bird Studies Canada. Project FeederWatch is made possible by the e are pleased to have a new efforts and support of thousands of citizen scientists. Wteam member on board! Meet Chelsea Benson, a new as- Project FeederWatch Staff sistant for Project FeederWatch. Chelsea will also be assisting with Cornell Lab of Ornithology NestWatch, another Cornell Lab Janis Dickinson citizen-science project. She will Director of Citizen Science be responding to your emails and Emma Greig phone calls and helping to keep Project Leader and Editor the website and social media pages Anne Marie Johnson Project Assistant up-to-date. Chelsea comes to us with a back- Chelsea Benson Project Assistant ground in environmental educa- Wesley Hochachka tion and conservation. She has worked with schools, community Senior Research Associate organizations, and local governments in her previous positions. Diane Tessaglia-Hymes She incorporated citizen science into her programming and into Design Director regional events like Day in the Life of the Hudson River. Chelsea holds a dual B.A. in psychology and English from Bird Studies Canada Allegheny College and an M.A. in Social Science, Environment Kerrie Wilcox and Community, from Humboldt State University. Project Leader We are excited that Chelsea has brought her energy and en- Rosie Kirton thusiasm to the Cornell Lab, where she will no doubt mobilize Project Support even more people to monitor bird feeders (and bird nests) for Kristine Dobney Project Assistant science. -

Ornamentation, Behavior, and Maternal Effects in the Female Northern Cardinal

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Summer 8-2011 Ornamentation, Behavior, and Maternal Effects in the Female Northern Cardinal Caitlin Winters University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Part of the Biology Commons, and the Ornithology Commons Recommended Citation Winters, Caitlin, "Ornamentation, Behavior, and Maternal Effects in the Female Northern Cardinal" (2011). Master's Theses. 240. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/240 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi ORNAMENTATION, BEHAVIOR, AND MATERNAL EFFECTS IN THE FEMALE NORTHERN CARDINAL by Caitlin Winters A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Approved: _Jodie M. Jawor_____________________ Director _Frank R. Moore_____________________ _Robert H. Diehl_____________________ _Susan A. Siltanen____________________ Dean of the Graduate School August 2011 ABSTRACT ORNAMENTATION, BEHAVIOR, AND MATERNAL EFFECTS IN THE FEMALE NORTHERN CARDINAL by Caitlin Winters August 2011 This study seeks to understand the relationship between ornamentation, maternal effects, and behavior in the female Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis). Female birds possess ornaments that indicate a number of important known aspects of quality and are usually costly to maintain. However, the extent to which female specific traits, such as maternal effects, are indicated is less clear. It is predicted by the Good Parent Hypothesis that this information should be displayed through intraspecific signal communication. -

Washita Battlefield National Historic Site Bird Checklist

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Southern Plains Inventory & Monitoring Network Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Washita Battlefield National Historic Monument Bird Checklist EXPERIENCE YOUR AMERICATM Washita Battlefield National Historic Site preserves and protects the site of the Battle of the Washita when the 7th US Cavalry under Lt. Col. George A. Custer attacked the Southern Cheyenne village of Peace Chief Black Kettle along the Washita River on November 27, 1868. The historic site promotes public understanding of the attack and the importance of the diverse perspectives related to the struggles that transpired between the Southern Great Plains tribes and the US government. The site’s natural landscape and cultural heritage are intertwined; both are managed to evoke a sense of place and reflect the setting of the Cheyenne encampment. The grasslands Northern and river bottoms were home to native cultures, and the native flora Cardinal and fauna were essential to the way of life for plains tribes. The park’s landscape contains a diversity of bird habitats ranging from the riparian area along the Washita River to grasslands and shrublands on the floodplain and uplands. At least 132 different species of birds have been documented in the historic site. Walking the park’s trail is the best way to view birds in the historic site. The 1.5-mile trail passes through grassland with sand sage and yucca before dropping down to the floodplain and the Washita River and then returning to the parking lot. Most of the wildlife that inhabit the Washita area are secretive in their activities. -

Passerines: Perching Birds

3.9 Orders 9: Passerines – perching birds - Atlas of Birds uncorrected proofs 3.9 Atlas of Birds - Uncorrected proofs Copyrighted Material Passerines: Perching Birds he Passeriformes is by far the largest order of birds, comprising close to 6,000 P Size of order Cardinal virtues Insect-eating voyager Multi-purpose passerine Tspecies. Known loosely as “perching birds”, its members differ from other Number of species in order The Northern or Common Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) The Common Redstart (Phoenicurus phoenicurus) was The Common Magpie (Pica pica) belongs to the crow family orders in various fine anatomical details, and are themselves divided into suborders. Percentage of total bird species belongs to the cardinal family (Cardinalidae) of passerines. once thought to be a member of the thrush family (Corvidae), which includes many of the larger passerines. In simple terms, however, and with a few exceptions, passerines can be described Like the various tanagers, grosbeaks and other members (Turdidae), but is now known to belong to the Old World Like many crows, it is a generalist, with a robust bill adapted of this diverse group, it has a thick, strong bill adapted to flycatchers (Muscicapidae). Its narrow bill is adapted to to feeding on anything from small animals to eggs, carrion, as small birds that sing. feeding on seeds and fruit. Males, from whose vivid red eating insects, and like many insect-eaters that breed in insects, and grain. Crows are among the most intelligent of The word passerine derives from the Latin passer, for sparrow, and indeed a sparrow plumage the family is named, are much more colourful northern Europe and Asia, this species migrates to Sub- birds, and this species is the only non-mammal ever to have is a typical passerine. -

Spring 2009 RURAL LIVING in ARIZONA Volume 3, Number 2

ARIZONA COOPERATIVE E TENSION THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND LIFE SCIENCES Backyards& Beyond Spring 2009 RURAL LIVING IN ARIZONA Volume 3, Number 2 Spring 2009 1 Common Name: Globemallow Scientific Name: Sphaeralcea spp. Globemallow is a common native wildflower found throughout most of Arizona. There are 16 species (and several varieties) occurring in the state, the majority of which are perennials. They are found between 1,000 and 6,000 feet in elevation and grow on a variety of soil types. Depending on the species, globemallows are either herbaceous or slightly woody at the base of the plant and grow between 2-3 feet in height (annual species may only grow to 6 inches). The leaves are three-lobed, and while the shape varies by species, they are similar enough to help identify the plant as a globemallow. The leaves have star-shaped hairs that give the foliage a gray-green color. Flower color Plant Susan Pater varies from apricot (the most common) to red, pink, lavender, pale yellow and white. Many of the globemallows flower in spring and again in summer. Another common name for globemallow is sore-eye poppy (mal de ojos in Spanish), from claims that the plant irritates the eyes. In southern California globemallows are known as plantas muy malas, translated to mean very bad plants. Ironically, the Pima Indian name for globemallow means a cure for sore eyes. The Hopi Indians used the plant for healing certain ailments and the stems as a type of chewing gum, and call the plant kopona. -

Variability and Distribution of the Golden-Headed Weevil Compsus Auricephalus (Say) (Curculionidae: Entiminae: Eustylini)

Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e55474 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.8.e55474 Single Taxon Treatment Variability and distribution of the golden-headed weevil Compsus auricephalus (Say) (Curculionidae: Entiminae: Eustylini) Jennifer C. Girón‡, M. Lourdes Chamorro§ ‡ Natural Science Research Laboratory, Museum of Texas Tech University, Lubbock, United States of America § Systematic Entomology Laboratory, ARS, USDA, c/o National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, United States of America Corresponding author: Jennifer C. Girón ([email protected]) Academic editor: Li Ren Received: 15 Jun 2020 | Accepted: 03 Jul 2020 | Published: 09 Jul 2020 Citation: Girón JC, Chamorro ML (2020) Variability and distribution of the golden-headed weevil Compsus auricephalus (Say) (Curculionidae: Entiminae: Eustylini). Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e55474. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.8.e55474 Abstract Background The golden-headed weevil Compsus auricephalus is a native and fairly widespread species across the southern U.S.A. extending through Central America south to Panama. There are two recognised morphotypes of the species: the typical green form, with pink to cupreous head and part of the legs and the uniformly white to pale brown form. There are other Central and South American species of Compsus and related genera of similar appearance that make it challenging to provide accurate identifications of introduced species at ports of entry. New information Here, we re-describe the species, provide images of the habitus, miscellaneous morphological structures and male and female genitalia. We discuss the morphological variation of Compsus auricephalus across its distributional range, by revising and updating This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC0 Public Domain Dedication. -

Northern Cardinal

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Northern Cardinal The bright red northern cardinal is the their favored black oil sunflower seeds U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service state bird in seven states – more than any are offered. Their large beak is especially National Wildlife Refuge System other species (Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, useful for crushing seeds. They also http://www.fws.gov/refuges North Carolina, Ohio, Virginia, West eat fruits and insects. Cardinals may Virginia). It is a year-round resident of lose their head feathers if they become June 2009 the Eastern United States, though it only infested with feather mites. They are not moved into the Northeast in the middle of able to preen on their heads, but when Find out More: the 20th century. the mites are gone, the feathers return. Cornell Lab of Ornithology www.birds.cornell.edu Cardinals will mate for life and stay together throughout the year. They don’t Wild Birds Forever migrate and often come to birdfeeders as www.birdsforever.com a couple. A male northern cardinal sings and leans from side to side to display his Orvis Beginner’s Guide to Birdwatching wings while attracting a female. Males by Alicia King (Rockport Publishers, fiercely defend their territory – if a male 2008) cardinal sees his reflection in glass, he will spend hours banging the class and The Young Birder’s Guide to Birds fighting the imaginary foe. of Eastern North America by Bill Thompson and Julie Zickefoose The male cardinal is entirely bright red (Houghton Mifflin, 2008) with a large crest on his head. The female is grayish-tan with red tail and wings. -

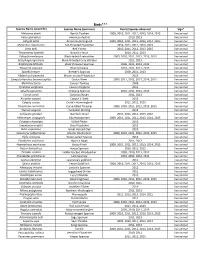

Flora and Fauna List.Xlsx

Birds*** Species Name (scientific) Species Name (common) Year(s) Species observed Sign* Melozone aberti Abert's Towhee 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Falco sparverius American Kestrel 2010, 2013 live animal Calypte anna Anna's Hummingbird 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Myiarchus cinerascens Ash‐throated Flycatcher 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Vireo bellii Bell's Vireo 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Thryomanes bewickii Bewick's Wren 2010, 2011, 2013 live animal Polioptila melanura Black‐tailed Gnatcatcher 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Setophaga nigrescens Black‐throated Gray Warbler 2011, 2013 live animal Amphispiza bilineata Black‐throated Sparrow 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Passerina caerulea Blue Grosbeak 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Spizella breweri Brewer's Sparrow 2009, 2011, 2013 live animal Myiarchus tryannulus Brown‐crested Flycatcher 2013 live animal Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus Cactus Wren 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Melozone fusca Canyon Towhee 2009 live animal Tyrannus vociferans Cassin's Kingbird 2011 live animal Spizella passerina Chipping Sparrow 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Corvus corax Common Raven 2011, 2013 live animal Accipiter cooperii Cooper's Hawk 2013 live animal Calypte costae Costa's Hummingbird 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Toxostoma curvirostre Curve‐billed Thrasher 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Sturnus vulgaris European Starling 2012 live animal Callipepla gambelii Gambel's