Bill Shape As a Generic Character in the Cardinals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2009 RURAL LIVING in ARIZONA Volume 3, Number 2

ARIZONA COOPERATIVE E TENSION THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND LIFE SCIENCES Backyards& Beyond Spring 2009 RURAL LIVING IN ARIZONA Volume 3, Number 2 Spring 2009 1 Common Name: Globemallow Scientific Name: Sphaeralcea spp. Globemallow is a common native wildflower found throughout most of Arizona. There are 16 species (and several varieties) occurring in the state, the majority of which are perennials. They are found between 1,000 and 6,000 feet in elevation and grow on a variety of soil types. Depending on the species, globemallows are either herbaceous or slightly woody at the base of the plant and grow between 2-3 feet in height (annual species may only grow to 6 inches). The leaves are three-lobed, and while the shape varies by species, they are similar enough to help identify the plant as a globemallow. The leaves have star-shaped hairs that give the foliage a gray-green color. Flower color Plant Susan Pater varies from apricot (the most common) to red, pink, lavender, pale yellow and white. Many of the globemallows flower in spring and again in summer. Another common name for globemallow is sore-eye poppy (mal de ojos in Spanish), from claims that the plant irritates the eyes. In southern California globemallows are known as plantas muy malas, translated to mean very bad plants. Ironically, the Pima Indian name for globemallow means a cure for sore eyes. The Hopi Indians used the plant for healing certain ailments and the stems as a type of chewing gum, and call the plant kopona. -

Variability and Distribution of the Golden-Headed Weevil Compsus Auricephalus (Say) (Curculionidae: Entiminae: Eustylini)

Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e55474 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.8.e55474 Single Taxon Treatment Variability and distribution of the golden-headed weevil Compsus auricephalus (Say) (Curculionidae: Entiminae: Eustylini) Jennifer C. Girón‡, M. Lourdes Chamorro§ ‡ Natural Science Research Laboratory, Museum of Texas Tech University, Lubbock, United States of America § Systematic Entomology Laboratory, ARS, USDA, c/o National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, United States of America Corresponding author: Jennifer C. Girón ([email protected]) Academic editor: Li Ren Received: 15 Jun 2020 | Accepted: 03 Jul 2020 | Published: 09 Jul 2020 Citation: Girón JC, Chamorro ML (2020) Variability and distribution of the golden-headed weevil Compsus auricephalus (Say) (Curculionidae: Entiminae: Eustylini). Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e55474. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.8.e55474 Abstract Background The golden-headed weevil Compsus auricephalus is a native and fairly widespread species across the southern U.S.A. extending through Central America south to Panama. There are two recognised morphotypes of the species: the typical green form, with pink to cupreous head and part of the legs and the uniformly white to pale brown form. There are other Central and South American species of Compsus and related genera of similar appearance that make it challenging to provide accurate identifications of introduced species at ports of entry. New information Here, we re-describe the species, provide images of the habitus, miscellaneous morphological structures and male and female genitalia. We discuss the morphological variation of Compsus auricephalus across its distributional range, by revising and updating This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC0 Public Domain Dedication. -

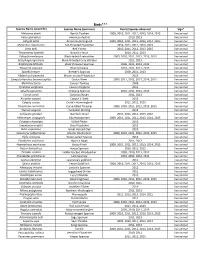

Flora and Fauna List.Xlsx

Birds*** Species Name (scientific) Species Name (common) Year(s) Species observed Sign* Melozone aberti Abert's Towhee 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Falco sparverius American Kestrel 2010, 2013 live animal Calypte anna Anna's Hummingbird 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Myiarchus cinerascens Ash‐throated Flycatcher 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Vireo bellii Bell's Vireo 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Thryomanes bewickii Bewick's Wren 2010, 2011, 2013 live animal Polioptila melanura Black‐tailed Gnatcatcher 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Setophaga nigrescens Black‐throated Gray Warbler 2011, 2013 live animal Amphispiza bilineata Black‐throated Sparrow 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Passerina caerulea Blue Grosbeak 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Spizella breweri Brewer's Sparrow 2009, 2011, 2013 live animal Myiarchus tryannulus Brown‐crested Flycatcher 2013 live animal Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus Cactus Wren 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Melozone fusca Canyon Towhee 2009 live animal Tyrannus vociferans Cassin's Kingbird 2011 live animal Spizella passerina Chipping Sparrow 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Corvus corax Common Raven 2011, 2013 live animal Accipiter cooperii Cooper's Hawk 2013 live animal Calypte costae Costa's Hummingbird 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Toxostoma curvirostre Curve‐billed Thrasher 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Sturnus vulgaris European Starling 2012 live animal Callipepla gambelii Gambel's -

Status and Occurrence of Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis Cardinalis) in British Columbia

Status and Occurrence of Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) in British Columbia. By Rick Toochin and Don Cecile. Submitted: April 15, 2018. Introduction and Distribution The Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) is a charismatic passerine found throughout eastern Canada, the eastern United States, throughout Mexico, Belize and the Petén part of northern Guatemala (Halkin and Linville 1999, Howell and Webb 2010). This species is a year round resident throughout its range, but is slowly expanding its range northward and westward across North America (Halkin and Linville 1999). Nearly 90% of banded individuals that were found dead came from same 10-minute block of latitude and longitude where they were initially banded, and those found dead at greater distances show no directional pattern in movements (Dow and Scott 1971). Reports of possible migration may be accounted for by dispersing juveniles (Halkin and Linville 1999). There is no known record of a breeding bird recovered at great distance in the following winter (Halkin and Linville 1999). The Northern Cardinal is found in areas with shrubs, small trees, including forest edges and interior, shrubby areas in logged and second-growth forests, marsh edges, grasslands with shrubs, successional fields, hedgerows in agricultural fields, and plantings around buildings (Dow 1969a, Dow 1969b, Emlen 1972a). In general, this species’ breeding range has expanded northward since the mid- 1800s, owing to 3 probable factors: warmer climate, resulting in lesser snow depth and greater winter foraging opportunities; human encroachment into forested areas, increasing suitable edge habitat; and establishment of winter feeding stations, increasing food availability (Halkin and Linville 1999). There are 18 subspecies of the Northern Cardinal; most are found in Mexico (Clements et al. -

Bird List of San Bernardino Ranch in Agua Prieta, Sonora, Mexico

Bird List of San Bernardino Ranch in Agua Prieta, Sonora, Mexico Melinda Cárdenas-García and Mónica C. Olguín-Villa Universidad de Sonora, Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico Abstract—Interest and investigation of birds has been increasing over the last decades due to the loss of their habitats, and declination and fragmentation of their populations. San Bernardino Ranch is located in the desert grassland region of northeastern Sonora, México. Over the last decade, restoration efforts have tried to address the effects of long deteriorating economic activities, like agriculture and livestock, that used to take place there. The generation of annual lists of the wildlife (flora and fauna) will be important information as we monitor the progress of restoration of this area. As part of our professional training, during the summer and winter (2011-2012) a taxonomic list of bird species of the ranch was made. During this season, a total of 85 species and 65 genera, distributed over 30 families were found. We found that five species are on a risk category in NOM-059-ECOL-2010 and 76 species are included in the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It will be important to continue this type of study in places that are at- tempting restoration and conservation techniques. We have observed a huge change, because of restoration activities, in the lands in the San Bernardino Ranch. Introduction migratory (Villaseñor-Gómez et al., 2010). Twenty-eight of those species are considered at risk on a global scale, and are included in Birds represent one of the most remarkable elements of our en- the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature vironment, because they’re easy to observe and it’s possible to find (IUCN). -

Comments on the Status of Revived Old Names for Some North American Birds

The Auk 112(3):633-648, 1995 COMMENTS ON THE STATUS OF REVIVED OLD NAMES FOR SOME NORTH AMERICAN BIRDS RICHARD C. BANKS AND M. RALPH BROWNING NationalBiological Service, National Museum of Natural History, MRC 111, Washington,D.C. 20560, USA AnSTRACT.--Wediscuss 44 instancesof the use of generic, specific,or subspecificnames that differ from those generally in use for North American (sensuAOU 1957) birds. These namesare generally older than the namespresently used and have been revived on the basis of priority. We examine the basisfor the proposedchanges and make recommendationsas to which namesshould properlybe usedin an effort to promotenomenclatural stability in accordancewith the InternationalCode of ZoologicalNomenclature. Received 22 February1994, accepted5 September1994. THEINTERNATIONAL COMMISSION of Zoological su AmericanOrnithologists' Union [AOU] 1957) Nomenclature (I.C.Z.N. 1985) promotesstabil- birds. ity in scientificnames of animals through the We do not discuss the use of old names that use of the InternationalCode of ZoologicalNo- are necessarilyrevived becausea taxon is di- menclature(hereinafter the Code). A primary vided into two or more taxa, unless there is an tenet of the Codeis the principle of priority, additional problem involved. Those situations which statesthat the earliestvalidly proposed are no less important, but require an analysis name for a genus or speciesshould be used, of validity of the basisof the "split," which is although some exceptionsare possible.There beyondthe scopeof this study.We do not dis- are, however, differencesof opinion about the cusschanges necessitated by decisionsof the validity and applicability of some early-pro- International Commissionon Zoological No- posednames. Furthermore, some sources of sci- menclature (hereinafter, the Commission) not- entific nameswere published before or after the ed by and incorporatedby the AOU (1973,1983) generally accepteddate of publication (Brown- unlessthe decisionhas been violated by an au- ing and Monroe 1991), a situation that can alter thor after 1973. -

February 2018 Volume 36 Issue I

February 2018 Chestnut-bellied Seed Finch (Sporophila angolensis) | Brazil 2017 Volume 36 Issue I Photo by LSUMNS graduate student Marco Rego February 2018 Volume 36, Issue 1 Letter from the Director... Museum of I am pleased to announce that legendary LSU ornithologist Natural Science Theodore “Ted” A. Parker, III (1953-1993) will be inducted into Director and the LSU College of Science Hall of Distinction at a ceremony on April 20th, 2018. Although I only knew Ted for a brief time, his Curators charisma, enthusiasm, and encyclopedic knowledge of birds were inspiring. Here I’ve posted an abridged version of the nomination letter that Gregg Gorton, Van Remsen, and I submitted. __________________________________________________________________ Robb T. Brumfield Director, Roy Paul Daniels Professor and Curator of Ted was already a legendary figure in ornithology and conservation before Genetic Resources his untimely death 25 years ago at age 40 on a cloud-enshrouded mountain in Ecuador while surveying habitats for establishing parks. The arc of his life and career Frederick H. Sheldon encompassed in breathtakingly rapid fashion a range of notable accomplishments. George H. Lowery, Jr., Professor and Curator of Genetic As a youngster, Ted was a birding prodigy with a nearly audiographic memory Resources whom some referred to as “the Mozart of ornithology,” and who broke the record for birds seen in one year in the United States while he was only 18 years old. He then Christopher C. Austin displayed field-ornithological genius by mastering the most challenging avifauna Curator of in the world--the 3500 bird species of South America--within a few years of going Amphibians & Reptiles there. -

Cardinal and Pyrrhuloxia

Friends of Ironwood Forest is a local non-profit organization that works for the permanent protection of the biological, geological, archaeological, and historical resources and values for which the Ironwood Forest National Monument was established. The Friends provide critical volunteer labor for projects on the Monument, working with the Bureau of Land Management and many other partners, and to increase community awareness through education, public outreach, and advocacy. Cardinal and Pyrrhuloxia by Young Cage Friends of Ironwood Forest Board of Directors from left: Pyrrhuloxia and cardinal. below: Phainopepla. © Young Cage Both newcomers and visitors to southern Arizona Tucson than the Cardinal, but still easily seen. I are often surprised to see Northern Cardinals also find them every bit as pretty with colors that (Cardinalis cardinalis) flying about in our desert. might be less brilliant than the Cardinal but very They seem out of place without the deep green forest pleasing and complimentary. Female Pyrrhuloxias foliage of the north and east United States. Yet they are brown, and not always easy to distinguish from thrive here, and are always a beautiful sight to see as the female Northern Cardinals. I use the bill shape they move about the Mesquites, Ironwoods, and and color to distinguish them. Their food even Cacti. While they may not be the state bird, (an preferences are similar to the Cardinals. honor reserved for the Cactus Wren) they are likely still our most recognizable bird and even have a A third bird that can be sports franchise named after them (the Arizona confusing is the Phainopepla, a Cardinals). -

Survey Protocol and Habitat Evaluation for Leconte's

Survey Protocol and Habitat Evaluation for LeConte’s (Toxostoma lecontei) and Bendire’s (Toxostoma bendirei) Thrasher Prepared by: The Desert Thrasher Working Group Survey Protocol and Habitat Evaluation Contents Objective 3 Field Gear and Materials Checklist: 4 Conducting the Survey 6 Thrasher Survey Form 8 Target Species Sighting Form 10 Habitat Evaluation Form 12 Data entry 16 Analysis of Area Search Data: Site-Level Models 17 Appendix 1. Species Descriptions 19 LeConte’s Thrasher 19 Bendire’s Thrasher 20 Appendix 2. Training Materials 22 Appendix 3. Bird and Plant Abbreviations and Codes 25 Appendix 4. Sample Survey Form 33 Appendix 5. Sample Sighting Form 34 Appendix 6. Group Code Examples 35 Appendix 7. Sample Habitat Evaluation Form 37 Appendix 8. Invasive Plant Identification Resources. 38 Recommended Citation: DTWG, the Desert Thrasher Working Group. 2018. Survey Protocol and Habitat Evaluation for LeConte’s and Bendire’sThrashers. The Protocol Subteam with the Desert Thrasher Working Group included: Dawn M. Fletcher, Lauren B. Harter, Christina L. Kondrat-Smith, Christofolos L. McCreedy and Collin A. Woolley. Cover photo art by: Christina Kondrat-Smith 2 Survey Protocol and Habitat Evaluation Objective The objectives of these surveys are to estimate distribution, determine population trends over time, and to identify habitat preferences for Bendire’s and LeConte’s Thrashers. Recommended Survey Times: Consider local elevation and latitude when designing a survey schedule, as researchers will need to balance surveying early (which helps to minimize confusion of adults with juveniles, and which may maximize exposure to peak singing season) with surveying late (which can minimize the possibility of completely missing late-arriving, migratory Bendire’s Thrashers). -

Learn About Texas Birds Activity Book

Learn about . A Learning and Activity Book Color your own guide to the birds that wing their way across the plains, hills, forests, deserts and mountains of Texas. Text Mark W. Lockwood Conservation Biologist, Natural Resource Program Editorial Direction Georg Zappler Art Director Elena T. Ivy Educational Consultants Juliann Pool Beverly Morrell © 1997 Texas Parks and Wildlife 4200 Smith School Road Austin, Texas 78744 PWD BK P4000-038 10/97 All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems – without written permission of the publisher. Another "Learn about Texas" publication from TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE PRESS ISBN- 1-885696-17-5 Key to the Cover 4 8 1 2 5 9 3 6 7 14 16 10 13 20 19 15 11 12 17 18 19 21 24 23 20 22 26 28 31 25 29 27 30 ©TPWPress 1997 1 Great Kiskadee 16 Blue Jay 2 Carolina Wren 17 Pyrrhuloxia 3 Carolina Chickadee 18 Pyrrhuloxia 4 Altamira Oriole 19 Northern Cardinal 5 Black-capped Vireo 20 Ovenbird 6 Black-capped Vireo 21 Brown Thrasher 7Tufted Titmouse 22 Belted Kingfisher 8 Painted Bunting 23 Belted Kingfisher 9 Indigo Bunting 24 Scissor-tailed Flycatcher 10 Green Jay 25 Wood Thrush 11 Green Kingfisher 26 Ruddy Turnstone 12 Green Kingfisher 27 Long-billed Thrasher 13 Vermillion Flycatcher 28 Killdeer 14 Vermillion Flycatcher 29 Olive Sparrow 15 Blue Jay 30 Olive Sparrow 31 Great Horned Owl =female =male Texas Birds More kinds of birds have been found in Texas than any other state in the United States: just over 600 species. -

Desert Birding in Arizona with a Focus on Urban Birds

Desert Birding in Arizona With a Focus on Urban Birds By Doris Evans Illustrations by Doris Evans and Kim Duffek A Curriculum Guide for Elementary Grades Tucson Audubon Society Urban Biology Program Funded by: Arizona Game & Fish Department Heritage Fund Grant Tucson Water Tucson Audubon Society Desert Birding in Arizona With a Focus on Urban Birds By Doris Evans Illustrations by Doris Evans and Kim Duffek A Curriculum Guide for Elementary Grades Tucson Audubon Society Urban Biology Program Funded by: Arizona Game & Fish Department Heritage Fund Grant Tucson Water Tucson Audubon Society Tucson Audubon Society Urban Biology Education Program Urban Birding is the third of several projected curriculum guides in Tucson Audubon Society’s Urban Biology Education Program. The goal of the program is to provide educators with information and curriculum tools for teaching biological and ecological concepts to their students through the studies of the wildlife that share their urban neighborhoods and schoolyards. This project was funded by an Arizona Game and Fish Department Heritage Fund Grant, Tucson Water, and Tucson Audubon Society. Copyright 2001 All rights reserved Tucson Audubon Society Arizona Game and Fish Department 300 East University Boulevard, Suite 120 2221 West Greenway Road Tucson, Arizona 85705-7849 Phoenix, Arizona 85023 Urban Birding Curriculum Guide Page Table of Contents Acknowledgements i Preface ii Section An Introduction to the Lessons One Why study birds? 1 Overview of the lessons and sections Lesson What’s That Bird? 3 One -

Standard Abbreviations for Common Names of Birds M

Standard abbreviations for common names of birds M. Kathleen Klirnkiewicz I and Chandler $. I•obbins 2 During the past two decadesbanders have taken The system we proposefollows five simple rules their work more seriouslyand have begun record- for abbreviating: ing more and more informationregarding the birds they are banding. To facilitate orderly record- 1. If the commonname is a singleword, use the keeping,bird observatories(especially Manomet first four letters,e.g., Canvasback, CANV. and Point Reyes)have developedstandard record- 2. If the common name consistsof two words, use ing forms that are now available to banders.These the first two lettersof the firstword, followed by forms are convenientfor recordingbanding data the first two letters of the last word, e.g., manually, and they are designed to facilitate Common Loon, COLO. automateddata processing. 3. If the common name consists of three words Because errors in species codes are frequently (with or without hyphens),use the first letter of detectedduring editing of bandingschedules, the the first word, the first letter of the secondword, Bird BandingOffices feel that bandersshould use and the first two lettersof the third word, e.g., speciesnames or abbreviationsthereof rather than Pied-billed Grebe, PBGR. only the AOU or speciescode numbers on their field sheets.Thus, it is essentialthat any recording 4. If the common name consists of four words form have provision for either common names, (with or without hypens), use the first letter of Latin names, or a suitable abbreviation. Most each word, •.g., Great Black-backed Gull, recordingforms presentlyin use have a 4-digit GBBG.