Dispersal and Vagrancy in the Pyrrhuloxia Michael A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lower Gila Region, Arizona

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR HUBERT WORK, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Water-Supply Paper 498 THE LOWER GILA REGION, ARIZONA A GEOGBAPHIC, GEOLOGIC, AND HTDBOLOGIC BECONNAISSANCE WITH A GUIDE TO DESEET WATEEING PIACES BY CLYDE P. ROSS WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1923 ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION MAT BE PROCURED FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 50 CENTS PEE COPY PURCHASER AGREES NOT TO RESELL OR DISTRIBUTE THIS COPT FOR PROFIT. PUB. RES. 57, APPROVED MAT 11, 1822 CONTENTS. I Page. Preface, by O. E. Melnzer_____________ __ xr Introduction_ _ ___ __ _ 1 Location and extent of the region_____._________ _ J. Scope of the report- 1 Plan _________________________________ 1 General chapters _ __ ___ _ '. , 1 ' Route'descriptions and logs ___ __ _ 2 Chapter on watering places _ , 3 Maps_____________,_______,_______._____ 3 Acknowledgments ______________'- __________,______ 4 General features of the region___ _ ______ _ ., _ _ 4 Climate__,_______________________________ 4 History _____'_____________________________,_ 7 Industrial development___ ____ _ _ _ __ _ 12 Mining __________________________________ 12 Agriculture__-_______'.____________________ 13 Stock raising __ 15 Flora _____________________________________ 15 Fauna _________________________ ,_________ 16 Topography . _ ___ _, 17 Geology_____________ _ _ '. ___ 19 Bock formations. _ _ '. __ '_ ----,----- 20 Basal complex___________, _____ 1 L __. 20 Tertiary lavas ___________________ _____ 21 Tertiary sedimentary formations___T_____1___,r 23 Quaternary sedimentary formations _'__ _ r- 24 > Quaternary basalt ______________._________ 27 Structure _______________________ ______ 27 Geologic history _____ _____________ _ _____ 28 Early pre-Cambrian time______________________ . -

Bill Shape As a Generic Character in the Cardinals

BILL SHAPE AS A GENERIC CHARACTER IN THE CARDINALS WALTER J. BOCK ANY genera in birds and other animal groups have been based essentially M upon a single character. This character may be a single morphological feature, such as the presence or absence of the hallux, or it may be a complex of characters which are all closely correlated functionally, such as the bones, muscles, and ligaments of the jaw apparatus. The validity of many of these genera has been questioned in recent years with the general acceptance of the polytypic species concept and the increasing acknowledgment of the grouping service at low taxonomic levels provided by the genus. An example is the North American passerine genus Pyrrhuloxia, which is distinguished from Richmondena essentially on the basis of bill shape. The overall similarity of Pyrrhuloxia sinuata to the two species of Richmondena in morphology and in general life history (Gould, 1961) has led several recent authors to synony- mize Richmondena with Pyrrhuloxia. Other workers have maintained the validity of the generic separation, basing their decision largely on the dif- ference in bill shape. The object of this paper is to ascertain the importance of this difference as a taxonomic character and whether the difference if con- firmed is of generic significance. THE JAW APPARATUS Ridgway (19013624-625) described the bill of P. sinuata (see Figs. 1 and 2) as follows: “Bill very short, thick and deep, with culmen strongly convex and maxillary tomium deeply and angularly incised a little posterior to the middle -

Spring 2009 RURAL LIVING in ARIZONA Volume 3, Number 2

ARIZONA COOPERATIVE E TENSION THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND LIFE SCIENCES Backyards& Beyond Spring 2009 RURAL LIVING IN ARIZONA Volume 3, Number 2 Spring 2009 1 Common Name: Globemallow Scientific Name: Sphaeralcea spp. Globemallow is a common native wildflower found throughout most of Arizona. There are 16 species (and several varieties) occurring in the state, the majority of which are perennials. They are found between 1,000 and 6,000 feet in elevation and grow on a variety of soil types. Depending on the species, globemallows are either herbaceous or slightly woody at the base of the plant and grow between 2-3 feet in height (annual species may only grow to 6 inches). The leaves are three-lobed, and while the shape varies by species, they are similar enough to help identify the plant as a globemallow. The leaves have star-shaped hairs that give the foliage a gray-green color. Flower color Plant Susan Pater varies from apricot (the most common) to red, pink, lavender, pale yellow and white. Many of the globemallows flower in spring and again in summer. Another common name for globemallow is sore-eye poppy (mal de ojos in Spanish), from claims that the plant irritates the eyes. In southern California globemallows are known as plantas muy malas, translated to mean very bad plants. Ironically, the Pima Indian name for globemallow means a cure for sore eyes. The Hopi Indians used the plant for healing certain ailments and the stems as a type of chewing gum, and call the plant kopona. -

Variability and Distribution of the Golden-Headed Weevil Compsus Auricephalus (Say) (Curculionidae: Entiminae: Eustylini)

Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e55474 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.8.e55474 Single Taxon Treatment Variability and distribution of the golden-headed weevil Compsus auricephalus (Say) (Curculionidae: Entiminae: Eustylini) Jennifer C. Girón‡, M. Lourdes Chamorro§ ‡ Natural Science Research Laboratory, Museum of Texas Tech University, Lubbock, United States of America § Systematic Entomology Laboratory, ARS, USDA, c/o National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, United States of America Corresponding author: Jennifer C. Girón ([email protected]) Academic editor: Li Ren Received: 15 Jun 2020 | Accepted: 03 Jul 2020 | Published: 09 Jul 2020 Citation: Girón JC, Chamorro ML (2020) Variability and distribution of the golden-headed weevil Compsus auricephalus (Say) (Curculionidae: Entiminae: Eustylini). Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e55474. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.8.e55474 Abstract Background The golden-headed weevil Compsus auricephalus is a native and fairly widespread species across the southern U.S.A. extending through Central America south to Panama. There are two recognised morphotypes of the species: the typical green form, with pink to cupreous head and part of the legs and the uniformly white to pale brown form. There are other Central and South American species of Compsus and related genera of similar appearance that make it challenging to provide accurate identifications of introduced species at ports of entry. New information Here, we re-describe the species, provide images of the habitus, miscellaneous morphological structures and male and female genitalia. We discuss the morphological variation of Compsus auricephalus across its distributional range, by revising and updating This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC0 Public Domain Dedication. -

Flora and Fauna List.Xlsx

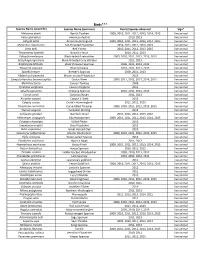

Birds*** Species Name (scientific) Species Name (common) Year(s) Species observed Sign* Melozone aberti Abert's Towhee 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Falco sparverius American Kestrel 2010, 2013 live animal Calypte anna Anna's Hummingbird 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Myiarchus cinerascens Ash‐throated Flycatcher 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Vireo bellii Bell's Vireo 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Thryomanes bewickii Bewick's Wren 2010, 2011, 2013 live animal Polioptila melanura Black‐tailed Gnatcatcher 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Setophaga nigrescens Black‐throated Gray Warbler 2011, 2013 live animal Amphispiza bilineata Black‐throated Sparrow 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Passerina caerulea Blue Grosbeak 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Spizella breweri Brewer's Sparrow 2009, 2011, 2013 live animal Myiarchus tryannulus Brown‐crested Flycatcher 2013 live animal Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus Cactus Wren 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Melozone fusca Canyon Towhee 2009 live animal Tyrannus vociferans Cassin's Kingbird 2011 live animal Spizella passerina Chipping Sparrow 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Corvus corax Common Raven 2011, 2013 live animal Accipiter cooperii Cooper's Hawk 2013 live animal Calypte costae Costa's Hummingbird 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Toxostoma curvirostre Curve‐billed Thrasher 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Sturnus vulgaris European Starling 2012 live animal Callipepla gambelii Gambel's -

Status and Occurrence of Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis Cardinalis) in British Columbia

Status and Occurrence of Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) in British Columbia. By Rick Toochin and Don Cecile. Submitted: April 15, 2018. Introduction and Distribution The Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) is a charismatic passerine found throughout eastern Canada, the eastern United States, throughout Mexico, Belize and the Petén part of northern Guatemala (Halkin and Linville 1999, Howell and Webb 2010). This species is a year round resident throughout its range, but is slowly expanding its range northward and westward across North America (Halkin and Linville 1999). Nearly 90% of banded individuals that were found dead came from same 10-minute block of latitude and longitude where they were initially banded, and those found dead at greater distances show no directional pattern in movements (Dow and Scott 1971). Reports of possible migration may be accounted for by dispersing juveniles (Halkin and Linville 1999). There is no known record of a breeding bird recovered at great distance in the following winter (Halkin and Linville 1999). The Northern Cardinal is found in areas with shrubs, small trees, including forest edges and interior, shrubby areas in logged and second-growth forests, marsh edges, grasslands with shrubs, successional fields, hedgerows in agricultural fields, and plantings around buildings (Dow 1969a, Dow 1969b, Emlen 1972a). In general, this species’ breeding range has expanded northward since the mid- 1800s, owing to 3 probable factors: warmer climate, resulting in lesser snow depth and greater winter foraging opportunities; human encroachment into forested areas, increasing suitable edge habitat; and establishment of winter feeding stations, increasing food availability (Halkin and Linville 1999). There are 18 subspecies of the Northern Cardinal; most are found in Mexico (Clements et al. -

Arizona's Wildlife Linkages Assessment

ARIZONAARIZONA’’SS WILDLIFEWILDLIFE LINKAGESLINKAGES ASSESSMENTASSESSMENT Workgroup Prepared by: The Arizona Wildlife Linkages ARIZONA’S WILDLIFE LINKAGES ASSESSMENT 2006 ARIZONA’S WILDLIFE LINKAGES ASSESSMENT Arizona’s Wildlife Linkages Assessment Prepared by: The Arizona Wildlife Linkages Workgroup Siobhan E. Nordhaugen, Arizona Department of Transportation, Natural Resources Management Group Evelyn Erlandsen, Arizona Game and Fish Department, Habitat Branch Paul Beier, Northern Arizona University, School of Forestry Bruce D. Eilerts, Arizona Department of Transportation, Natural Resources Management Group Ray Schweinsburg, Arizona Game and Fish Department, Research Branch Terry Brennan, USDA Forest Service, Tonto National Forest Ted Cordery, Bureau of Land Management Norris Dodd, Arizona Game and Fish Department, Research Branch Melissa Maiefski, Arizona Department of Transportation, Environmental Planning Group Janice Przybyl, The Sky Island Alliance Steve Thomas, Federal Highway Administration Kim Vacariu, The Wildlands Project Stuart Wells, US Fish and Wildlife Service 2006 ARIZONA’S WILDLIFE LINKAGES ASSESSMENT First Printing Date: December, 2006 Copyright © 2006 The Arizona Wildlife Linkages Workgroup Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written consent from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written consent of the copyright holder. Additional copies may be obtained by submitting a request to: The Arizona Wildlife Linkages Workgroup E-mail: [email protected] 2006 ARIZONA’S WILDLIFE LINKAGES ASSESSMENT The Arizona Wildlife Linkages Workgroup Mission Statement “To identify and promote wildlife habitat connectivity using a collaborative, science based effort to provide safe passage for people and wildlife” 2006 ARIZONA’S WILDLIFE LINKAGES ASSESSMENT Primary Contacts: Bruce D. -

Bird List of San Bernardino Ranch in Agua Prieta, Sonora, Mexico

Bird List of San Bernardino Ranch in Agua Prieta, Sonora, Mexico Melinda Cárdenas-García and Mónica C. Olguín-Villa Universidad de Sonora, Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico Abstract—Interest and investigation of birds has been increasing over the last decades due to the loss of their habitats, and declination and fragmentation of their populations. San Bernardino Ranch is located in the desert grassland region of northeastern Sonora, México. Over the last decade, restoration efforts have tried to address the effects of long deteriorating economic activities, like agriculture and livestock, that used to take place there. The generation of annual lists of the wildlife (flora and fauna) will be important information as we monitor the progress of restoration of this area. As part of our professional training, during the summer and winter (2011-2012) a taxonomic list of bird species of the ranch was made. During this season, a total of 85 species and 65 genera, distributed over 30 families were found. We found that five species are on a risk category in NOM-059-ECOL-2010 and 76 species are included in the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It will be important to continue this type of study in places that are at- tempting restoration and conservation techniques. We have observed a huge change, because of restoration activities, in the lands in the San Bernardino Ranch. Introduction migratory (Villaseñor-Gómez et al., 2010). Twenty-eight of those species are considered at risk on a global scale, and are included in Birds represent one of the most remarkable elements of our en- the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature vironment, because they’re easy to observe and it’s possible to find (IUCN). -

Section Four—Open Space Element

Open Space Element Section Four—Open Space Element 4.1 Introduction There are many ways that open space can be defined, but the following definition of open space is the one used in the Yuma County 2020 Comprehensive Plan. Open space is defined as any publicly owned and publicly accessible space or area characterized by great natural scenic beauty or whose existing openness, natural condition or present state of use, if retained, would maintain or enhance the conservation of natural or scenic resources. Arizona Revised Statutes §11-821(D)(1) requires that an open space element contained in a comprehensive plan have the following components: A comprehensive inventory of open space areas, recreational resources and designation of access points to open space areas and resources; an analysis of forecasted needs, policies for managing and protecting open space areas and re- sources and implementation strategies to acquire open space areas and further establish recrea- tional resources; and policies and implementation strategies designed to promote a regional sys- tem of integrated open space and recreational resources and a consideration of any existing re- gional open space plan. A rich variety of open spaces exists within Yuma County. Only a very small portion of the County is urbanized and over 91% of the unincorporated Yuma County is publicly owned. Much of the federally owned land and a small portion of state owned land in Yuma County is specifically designated and managed as open space areas. A comprehensive inventory of these designated open space areas as required under ARS §11-821(D)(1)(a) is contained in this ele- ment. -

Comments on the Status of Revived Old Names for Some North American Birds

The Auk 112(3):633-648, 1995 COMMENTS ON THE STATUS OF REVIVED OLD NAMES FOR SOME NORTH AMERICAN BIRDS RICHARD C. BANKS AND M. RALPH BROWNING NationalBiological Service, National Museum of Natural History, MRC 111, Washington,D.C. 20560, USA AnSTRACT.--Wediscuss 44 instancesof the use of generic, specific,or subspecificnames that differ from those generally in use for North American (sensuAOU 1957) birds. These namesare generally older than the namespresently used and have been revived on the basis of priority. We examine the basisfor the proposedchanges and make recommendationsas to which namesshould properlybe usedin an effort to promotenomenclatural stability in accordancewith the InternationalCode of ZoologicalNomenclature. Received 22 February1994, accepted5 September1994. THEINTERNATIONAL COMMISSION of Zoological su AmericanOrnithologists' Union [AOU] 1957) Nomenclature (I.C.Z.N. 1985) promotesstabil- birds. ity in scientificnames of animals through the We do not discuss the use of old names that use of the InternationalCode of ZoologicalNo- are necessarilyrevived becausea taxon is di- menclature(hereinafter the Code). A primary vided into two or more taxa, unless there is an tenet of the Codeis the principle of priority, additional problem involved. Those situations which statesthat the earliestvalidly proposed are no less important, but require an analysis name for a genus or speciesshould be used, of validity of the basisof the "split," which is although some exceptionsare possible.There beyondthe scopeof this study.We do not dis- are, however, differencesof opinion about the cusschanges necessitated by decisionsof the validity and applicability of some early-pro- International Commissionon Zoological No- posednames. Furthermore, some sources of sci- menclature (hereinafter, the Commission) not- entific nameswere published before or after the ed by and incorporatedby the AOU (1973,1983) generally accepteddate of publication (Brown- unlessthe decisionhas been violated by an au- ing and Monroe 1991), a situation that can alter thor after 1973. -

February 2018 Volume 36 Issue I

February 2018 Chestnut-bellied Seed Finch (Sporophila angolensis) | Brazil 2017 Volume 36 Issue I Photo by LSUMNS graduate student Marco Rego February 2018 Volume 36, Issue 1 Letter from the Director... Museum of I am pleased to announce that legendary LSU ornithologist Natural Science Theodore “Ted” A. Parker, III (1953-1993) will be inducted into Director and the LSU College of Science Hall of Distinction at a ceremony on April 20th, 2018. Although I only knew Ted for a brief time, his Curators charisma, enthusiasm, and encyclopedic knowledge of birds were inspiring. Here I’ve posted an abridged version of the nomination letter that Gregg Gorton, Van Remsen, and I submitted. __________________________________________________________________ Robb T. Brumfield Director, Roy Paul Daniels Professor and Curator of Ted was already a legendary figure in ornithology and conservation before Genetic Resources his untimely death 25 years ago at age 40 on a cloud-enshrouded mountain in Ecuador while surveying habitats for establishing parks. The arc of his life and career Frederick H. Sheldon encompassed in breathtakingly rapid fashion a range of notable accomplishments. George H. Lowery, Jr., Professor and Curator of Genetic As a youngster, Ted was a birding prodigy with a nearly audiographic memory Resources whom some referred to as “the Mozart of ornithology,” and who broke the record for birds seen in one year in the United States while he was only 18 years old. He then Christopher C. Austin displayed field-ornithological genius by mastering the most challenging avifauna Curator of in the world--the 3500 bird species of South America--within a few years of going Amphibians & Reptiles there. -

Final Environmental Impact Statement MX: Buried Trench Construction

ADV-AI0 352 AIR FORCE SYSTEMS COMMAND WASHINGTON OC F/G 13/2 NOV 77ENVIRONMENTALIMPACT STATEMENT MX: BURIED TRENCH CONSTRUCTION A--ETCttI) UNCLASSIF IED AFSC-TP-81-50 1 EIIIIlNL *IMENMONEEl IIIIiiiiii EIIhIhIhIoE- Unclassified SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF THIS PAGE (When Dal. Enftered) REPORT DOCUMENTATIDN PAPE RFAD INSTRUCTIONS 'EFORFCOMPILETING FORM It REPORT 64UMaER " 2 GOVT ACCESSION NO. 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NUMBER // AFSC-TR-81-50 . TIT.LE (and Subtitle) 5. TYPE OF REPORT & PERIOD COVERED Fina"l_ Environmental Impact Statement Final 1977-78 MX: Buried Trench Construction and Test Project- 6 PERFORMING O1G. REPORT NUMBER 7 AUTHOR(s) / B. CONTRACT 0R GRANT NUBER(s) Henningson, Durham & Richardson -- Santa Barbara CA 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS AREAQRK UNIT NUMBERS 63305 6,_, 1 CONTROLLING OFFICE NAME AND ADDRESS 12. REPORT DATE Deputy for Environment and Safety N// Office of the Secretary of the AF(SAF/MIQ) 50- Washington DC 20330 14 MONITORING AGENCY NAME & ADDRESS(,f different fron (,o-troIiing Office) 15. SECURITY CLASS. (of this report) ICBM System Program office Unclassified Space & Missile Systems Organization (SAMS),. DECLASSI FCATON DOWNGRADING Norton AFB California SCHEDULE 16. DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT (of thi, Report) Unclassified Unlimited J 17 DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT (of the abstract entered ,, Block 20, if different from Report) IS. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 19. KEY WORDS (Continue on reverse side if necessary and Identify by block number) Environmental Impact Statements Air Force MX Buried Trench Concept 20. ABSTRACT (Continue on reverse side If necessary and Identify by block number) The United States Air Force proposes to construct two sections of underground tunnel in the San Cristobal Valley on the Luke Air Force Range in Yuma County, Arizona.