Riparian Research and Management: Past, Present, Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fitness Costs and Benefits of Egg Ejection by Gray Catbirds

FITNESS COSTS AND BENEFITS OF EGG EJECTION BY GRAY CATBIRDS BY JANICE C. LORENZANA Ajhesis presented to the University of Manitoba in fulfillment of the thesis requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Department of Zoology Winnipeg, Manitoba Janice C. Lorenzana (C) April 1999 National Library Bibfiot hèque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395,rue Wellington Ottawa ON K 1A ON4 Onawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your ble Vorre derence Our fi& Narre fetefmce The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microforni. vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fi-orn it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Canada THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STZTDIES ***** COPYRIGEIT PERMISSION PAGE Fitness Costs and Benefits of Egg Ejection by Gray Catbirds BY Janice C. Lorenzana A Thesis/Practicurn submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial Mfiilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Permission has been granted to the Library of The University of Manitoba to lend QB sell copies of this thesis/practicum, to the National Library of Canada to microfilm this thesis and to lend or seli copies of the film, and to Dissertations Abstracts International to publish an abstract of this thesis/practicum. -

Rare Birds of California Now Available! Price $54.00 for WFO Members, $59.99 for Nonmembers

Volume 40, Number 3, 2009 The 33rd Report of the California Bird Records Committee: 2007 Records Daniel S. Singer and Scott B. Terrill .........................158 Distribution, Abundance, and Survival of Nesting American Dippers Near Juneau, Alaska Mary F. Willson, Grey W. Pendleton, and Katherine M. Hocker ........................................................191 Changes in the Winter Distribution of the Rough-legged Hawk in North America Edward R. Pandolfino and Kimberly Suedkamp Wells .....................................................210 Nesting Success of California Least Terns at the Guerrero Negro Saltworks, Baja California Sur, Mexico, 2005 Antonio Gutiérrez-Aguilar, Roberto Carmona, and Andrea Cuellar ..................................... 225 NOTES Sandwich Terns on Isla Rasa, Gulf of California, Mexico Enriqueta Velarde and Marisol Tordesillas ...............................230 Curve-billed Thrasher Reproductive Success after a Wet Winter in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona Carroll D. Littlefield ............234 First North American Records of the Rufous-tailed Robin (Luscinia sibilans) Lucas H. DeCicco, Steven C. Heinl, and David W. Sonneborn ........................................................237 Book Reviews Rich Hoyer and Alan Contreras ...........................242 Featured Photo: Juvenal Plumage of the Aztec Thrush Kurt A. Radamaker .................................................................247 Front cover photo by © Bob Lewis of Berkeley, California: Dusky Warbler (Phylloscopus fuscatus), Richmond, Contra Costa County, California, 9 October 2008, discovered by Emilie Strauss. Known in North America including Alaska from over 30 records, the Dusky is the Old World Warbler most frequent in western North America south of Alaska, with 13 records from California and 2 from Baja California. Back cover “Featured Photos” by © Kurt A. Radamaker of Fountain Hills, Arizona: Aztec Thrush (Ridgwayia pinicola), re- cently fledged juvenile, Mesa del Campanero, about 20 km west of Yecora, Sonora, Mexico, 1 September 2007. -

Godbois-222-227.Pdf

222 Author’s name Bobcat Diet on an Area Managed for Northern Bobwhite Ivy A. Godbois, Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center, Newton, GA 39870 L. Mike Conner, Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center, Newton, GA 39870 Robert J. Warren, Warnell School of Forest Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602 Abstract: We quantified bobcat (Lynx rufus) diet on a longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) dominated area managed for northern bobwhite (Colinus virginianus), hereafter quail. We sorted prey items to species when possible, but for analysis we categorized them into 1 of 5 classes: rodent, bird, deer, rabbit, and other species. Bobcat diet did not dif- fer seasonally (X2 = 17.82, P = 0.1213). Most scats (91%) contained rodent, 14% con- tained bird, 9% contained deer (Odocoileus virginianus), 6% contained rabbit (Sylvila- gus sp.), and 12% contained other. Quail remains were detected in only 2 of 135 bobcat scats examined. Because of low occurrence of quail (approximately 1.4%) in bobcat scats we suggest that bobcats are not a serious predator of quail. Key Words: bobcat, diet, Georgia, Lynx rufus Proc. Annu. Conf. Southeast. Assoc. Fish and Wildl. Agencies 57:222–227 Bobcats are opportunistic in their feeding habits, and their diet often reflects prey availability (Latham 1951). In the Southeast, bobcats prey most heavily on small mammals such as rabbits and cotton rats (Davis 1955, Beasom and Moore 1977, Miller and Speake 1978, Maehr and Brady 1986, Baker et al. 2001). In some regions, bobcats also consume deer. Deer consumption is often highest during fall- winter when there is the possibility for hunter-wounded deer to be consumed and during spring-summer when fawns are available as prey (Buttrey 1979, Story et al. -

Chihuahuan Raven)

REGION 2 SENSITIVE SPECIES EVALUATION FORM Species: (Corvus cryptoleucus/Chihuahuan Raven) Criteria Rank Rationale Literature Citations • Andrews & Righter 1 A High. The Chihuahuan Raven is limited in breeding distribution to the great plains of southeastern Colorado • Kingery Distribution and extreme southwestern Kansas. • Busby & Zimmerman within R2 • Ehrlich et al. 2 C High. This species breeds from southeastern Colorado, south through western Texas, southern Arizona • National Geographic Society Distribution and New Mexico to southern Mexico. outside R2 • Andrews & Righter 3 C High. Population expansions and contractions have been documented over the past 150 years. This • Busby & Zimmerman Dispersal species is relatively mobile. They tend to move in roving flocks after the nesting season. • Kingery Capability • Andrews & Righter 4 A High. Small, relatively isolated populations are confined primarily to southeastern Colorado and • Carter et al. Abundance in southwestern Kansas. In southwestern Kansas only 12 known nest sites have been located and several of • Busby & Zimmerman R2 those are on or near the Cimarron National Grasslands. A significant percentage of the population in Colorado occurs on the Comanche National Grasslands. • Carter et al. 5 A Low. The breeding bird survey shows nearly an eight percent decline from 1966 to 1999. However the • Kingery Population amount of data is seriously lacking to provide accurate projections. One report observed a decline of 10 • Breeding Bird Survey Trend in R2 active nests in a colony to only one active nest in Colorado from 1990 to 1995. The Partners In Flight analysis shows a moderate decline for this species in R2. • Carter et al. 6 C High. -

Columbina Minuta (Plain-Breasted Ground Dove) Family: Columbidae (Pigeons and Doves) Order: Columbiformes (Pigeons, Doves and Dodos) Class: Aves (Birds)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology Columbina minuta (Plain-breasted Ground Dove) Family: Columbidae (Pigeons and Doves) Order: Columbiformes (Pigeons, Doves and Dodos) Class: Aves (Birds) Fig. 1. Plain-breasted ground dove, Columbina minuta. [http://neotropical.birds.cornell.edu/portal/species/overview?p_p_spp=173941, downloaded 21 February 2017] TRAITS. Columbina minuta is a species of ground-dwelling dove which measures 14.5-16.0cm long and weighs 26-42g (Soberanes-Gonzalez et al., 2010). It has reddish eyes, and dark grey and brown feathers, with the wings paler and with dark violet spots (Fig. 1) and mostly rufous (reddish) underwings. Tail feathers to the centre are grey-brown with the outer being very dark and narrowly tipped white. Pink legs. There is a distinction between males and females. Male: blue-grey nape and crown with bill being grey and tipped black. The neck, face, chest and belly areas are grey. Female: overall appear duller than males. Nape and crown are grey. Grey bill. Neck face and chest are pale grey with the area of the throat and belly being much paler. Juveniles display similar characteristics to females. This species may be confused with the ruddy ground dove Columbina talpacoti and the common ground dove Columbina passerina but there are distinctions, with the former being duller and not as rufous and the latter having a speckled neck and head. DISTRIBUTION. Although it has a very wide distribution, it is very discontinuous and occurs from the south of Mexico, through Central America to Colombia, over the north of South America onto Trinidad and the Guianas. -

Landbird Monitoring Protocol and Standard Operating

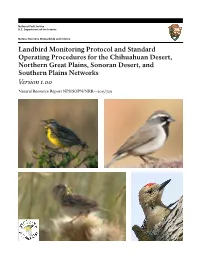

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Landbird Monitoring Protocol and Standard Operating Procedures for the Chihuahuan Desert, Northern Great Plains, Sonoran Desert, and Southern Plains Networks Version 1.00 Natural Resource Report NPS/SOPN/NRR—2013/729 ON THE COVER Upper left: Western Meadowlark (Sturnella neglecta)1, one of the most common species for SOPN. Upper right: Black-throated Sparrow (Amphispiza bilineata)2, one of the most common species for CHDN. Lower left: Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum)3, one of the most common species for NGPN. Lower right: Gila Woodpecker (Melanerpes uropygialis)2, one of the most common species for SODN. 1Photo © John and Karen Hollingsworth 2Photo © Robert Shantz 3Photographer Dan Licht - NPS. Landbird Monitoring Protocol and Standard Operating Procedures for the Chihuahuan Desert, Northern Great Plains, Sonoran Desert, and Southern Plains Networks Version 1.00 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SOPN/NRTR—2013/729 Authors (listed alphabetically) 4National Park Service Kristen Beaupré1 Chihuahuan Desert Network Robert E. Bennetts2 New Mexico State University Jennifer A. Blakesley3 3655 Research Dr., Genesis Building D Kirsten Gallo4 Las Cruces, NM 88003 David Hanni3 Andy Hubbard1 5USGS Southwest Biological Science Center Ross Lock3 Sonoran Desert Research Station Brian F. Powell5 School of Natural Resources Heidi Sosinski2 University of Arizona Patricia Valentine-Darby6 Tucson, Arizona 85721 Chris White3 Marcia Wilson7 6University of West Florida Department of Biology 11000 University Parkway 1National Park Service Pensacola, Florida 32514 Sonoran Desert Network 7660 E. Broadway Blvd., Suite #303 7National Park Service Tucson, Arizona 85710 Northern Great Plains Network 231 East St. -

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

Riqueza De Espécies E Relevância Para a Conservação

O Brasil é reconhecidamente um dos países de megadiversidade de mamíferos do mundo, abrigando cerca de 12% de todas as espécies desse grupo existentes no nosso planeta, distribuídas em 12 Ordens e 50 Famílias. Dentre as espécies que ocorrem no País, 210 (30% do total) são exclusivas do território brasileiro. Esses números não só indicam a importância do País para a conservação mundial desses animais como também trazem para a mastozoologia brasileira a responsabilidade de produzir e disseminar conhecimento científico de qualidade sobre um grupo carismático, bastante ameaçado pela ação antrópica e importante componente dos ecossistemas naturais. O próprio aumento no número de espécies reconhecidas para o Brasil nos últimos 15 anos já é um indicativo da resposta que vem sendo dada pelos pesquisadores do País a esse desafio de gerar conhecimento científico de qualidade sobre os mamíferos. Na publicação pioneira de Fonseca e colaboradores (Lista Anotada dos Mamíferos do Brasil, 1996), houve a indicação de 524 espécies brasileiras de mamíferos. Na compilação mais recente, de 2012, esse número passou para 701, o que representa um aumento de quase 34% em 16 anos (Paglia et al., Lista Anotada dos Mamíferos do Brasil , 2a ed., 2012). Visando contribuir para essa produção de conhecimento científico de qualidade sobre mamíferos, há alguns anos atrás nós organizamos uma publicação que reunia estudos científicos inéditos sobre vários aspectos da biologia do grupo, intitulada Mamíferos do Brasil: Genética, Sistemática, Ecologia e Conservação. Esse livro, publicado em 2006, contou com a participação de vários mastozoólogos brasileiros de destaque. A nossa intenção, com o mesmo, era contribuir para a produção e divulgação da informação científica para um público mais amplo, incluindo alunos de graduação e não-acadêmicos interessados em mastozoologia, além é claro dos pesquisadores especialistas na área. -

October–December 2014 Vermilion Flycatcher Tucson Audubon 3 the Sky Island Habitat

THE QUARTERLY NEWS MAGAZINE OF TUCSON AUDUBON SOCIETY | TUCSONAUDUBON.ORG VermFLYCATCHERilion October–December 2014 | Volume 59, Number 4 Adaptation Stormy Weather ● Urban Oases ● Cactus Ferruginous Pygmy-Owl What’s in a Name: Crissal Thrasher ● What Do Owls Need for Habitat ● Tucson Meet Your Birds Features THE QUARTERLY NEWS MAGAZINE OF TUCSON AUDUBON SOCIETY | TUCSONAUDUBON.ORG 12 What’s in a Name: Crissal Thrasher 13 What Do Owls Need for Habitat? VermFLYCATCHERilion 14 Stormy Weather October–December 2014 | Volume 59, Number 4 16 Urban Oases: Battleground for the Tucson Audubon Society is dedicated to improving the Birds quality of the environment by providing environmental 18 The Cactus Ferruginous Pygmy- leadership, information, and programs for education, conservation, and recreation. Tucson Audubon is Owl—A Prime Candidate for Climate a non-profit volunteer organization of people with a Adaptation common interest in birding and natural history. Tucson 19 Tucson Meet Your Birds Audubon maintains offices, a library, nature centers, and nature shops, the proceeds of which benefit all of its programs. Departments Tucson Audubon Society 4 Events and Classes 300 E. University Blvd. #120, Tucson, AZ 85705 629-0510 (voice) or 623-3476 (fax) 5 Events Calendar Adaptation All phone numbers are area code 520 unless otherwise stated. 6 Living with Nature Lecture Series Stormy Weather ● Urban Oases ● Cactus Ferruginous Pygmy-Owl tucsonaudubon.org What’s in a Name: Crissal Thrasher ● What Do Owls Need for Habitat ● Tucson Meet Your Birds 7 News Roundup Board Officers & Directors President—Cynthia Pruett Secretary—Ruth Russell 20 Conservation and Education News FRONT COVER: Western Screech-Owl by Vice President—Bob Hernbrode Treasurer—Richard Carlson 24 Birding Travel from Our Business Partners Guy Schmickle. -

Effects of Experimental Noise Exposure on Songbird Nesting Behaviors and Nest Success

EFFECTS OF EXPERIMENTAL NOISE EXPOSURE ON SONGBIRD NESTING BEHAVIORS AND NEST SUCCESS A Thesis presented to the Faculty of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters of Science in Biological Sciences by Tracy Irene Mulholland August 2016 © 2016 Tracy Irene Mulholland ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP TITLE: Effects of Experimental Noise Exposure on Songbird Nesting Behaviors and Nest Success AUTHOR: Tracy Irene Mulholland DATE SUBMITTED: August 2016 COMMITTEE CHAIR: Clinton D. Francis, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences COMMITTEE MEMBER: Emily Taylor, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Biological Sciences COMMITTEE MEMBER: Sean Lema, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Biological Sciences iii ABSTRACT Effects of Experimental Noise Exposure on Songbird Nesting Behaviors and Nest Success Tracy Irene Mulholland Anthropogenic noise is an increasingly prevalent global disturbance. Animals that rely on the acoustical environment, such as songbirds, are especially vulnerable to these sounds. Traffic noise, in particular, overlaps with the frequency range of songbirds, creating masking effects. We investigated the effects of chronic traffic noise on provisioning behaviors and breeding success of nesting western bluebirds (Sialia mexicana) and ash-throated flycatchers (Myiarchus cinerascens). Because anthropogenic noise exposure has the potential to interrupt parent-offspring communication and alter vigilance behaviors, we predicted that traffic noise would lead to changes in provisioning behaviors, such as fewer visits to the nest box, for each species. We also predicted the noise to negatively influence one or more metrics reflective of reproductive success, such as nest success, clutch size, number of nestlings or number of fledglings. -

The Status and Occurrence of Black Phoebe (Sayornis Nigricans) in British Columbia

The Status and Occurrence of Black Phoebe (Sayornis nigricans) in British Columbia. By Rick Toochin. Introduction and Distribution The Black Phoebe (Sayornis nigricans) is a small passerine belonging to the tyrant-flycatcher family. The Black Phoebe occurs as a year-round resident throughout most of its range; however, its northern populations are partially migratory (Wahl et al. 2005). It is a species found throughout the year from southwestern Oregon south, through California including the Baja Peninsula (excluding the central regions of the Peninsula), east through Arizona, New Mexico, southern Colorado, west Texas, south through Mexico, Central America to Panama (excluding El Salvador) and in South America from the coastal mountains of Venezuela, through Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, to western Bolivia and northwestern Argentina (Sibley 2000, Howell and Webb 2010, Hoyo et al. 2006). In the past couple of decades the Black Phoebe has been slowly expanding its known range northward into northern Oregon and southern Washington where it is still considered a very rare visitor, but with records increasing every year (Wahl et al. 2005, WBRC 2012). The Black Phoebe has been recorded from Idaho, Nevada, Utah, southern Oklahoma and Florida (Sibley 2000). The Black Phoebe is an accidental visitor to south-central Alaska (Gibson et al. 2013). In British Columbia this species is considered a casual visitor but Provincial records, like those of Washington State, are on the rise and the status of this species in British Columbia could change in the near future. Identification and Similar Species The Black Phoebe has a huge range that encompasses two continents. -

Landbird Monitoring in the Sonoran Desert Network 2012 Annual Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Landbird Monitoring in the Sonoran Desert Network 2012 Annual Report Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SODN/NRTR—2013/744 ON THE COVER Hooded Oriole (Icterus cucullatus). Photo by Moez Ali. Landbird Monitoring in the Sonoran Desert Network 2012 Annual Report Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SODN/NRTR—2013/744 Authors Moez Ali Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory 230 Cherry Street, Suite 150 Fort Collins, Colorado 80521 Kristen Beaupré National Park Service Sonoran Desert Network 7660 E. Broadway Blvd, Suite 303 Tucson, Arizona 85710 Patricia Valentine-Darby University of West Florida Department of Biology 11000 University Parkway Pensacola, Florida 32514 Chris White Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory 230 Cherry Street, Suite 150 Fort Collins, Colorado 80521 Project Contact Robert E. Bennetts National Park Service Southern Plains Network Capulin Volcano National Monument PO Box 40 Des Moines, New Mexico 88418 May 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colora- do, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource manage- ment, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission.