Final Programmatic Environmental Assessment: Wildfire Hazard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long-Term Strategy for Russian Olive and Saltcedar Management

LONG-TERM STRATEGY FOR RUSSIAN OLIVE AND SALTCEDAR MANAGEMENT YELLOWSTONE RIVER CONSERVATION DISTRICT COUNCIL Prepared by Thomas L. Pick, Bozeman, Montana May 1, 2013 Cover photo credit: Tom Pick. Left side: Plains cottonwood seedlings on bar following 2011 runoff. Top: Saltcedar and Russian olive infest the shoreline of the Yellowstone River between Hysham and Forsyth, Montana. Bottom: A healthy narrowleaf cottonwood (Populus angustifolia James) stand adjacent to the channel provides benefits for wildlife and livestock in addition to bank stability and storing floodwater for later release. Table of Contents page number Agreement ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….1 Executive Summary …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….2 Long-Term Strategy for Russian Olive and Saltcedar Management 1.0 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………4 1.1 Biology and Ecology of Russian Olive and Saltcedar ……………………………………………………5 1.12 Russian Olive 1.13 Saltcedar 1.2 Distribution and Spread……………………………………………………………………………………………..6 1.3 Summary of Impacts ………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 1.4 Legal Framework ……………………………………………………………………………………………………….7 2.0 Strategic Management Objective and Goals ………………………………………………………………..…..8 2.1 Goal 1: Prevent New Infestations (Control Spread) …………………………………….……….……8 2.2 Goal 2: Eradicate All Infestations Within the River Corridor ………………………………………9 2.3 Goal 3: Manage Populations Outside of the River Corridor ……………………………………….9 3.0 Treatment Strategies and Priorities …………………………………….……………………………………………9 -

Castilleja Publication of the Wyoming Native Plant Society December 2012, Volume 31(4) Posted at Castilleja Linariifolia

Castilleja Publication of the Wyoming Native Plant Society December 2012, Volume 31(4) Posted at www.wynps.org Castilleja linariifolia In this issue: Desert Yellowhead . 1 Botanists Bookshelf - Intermountain Flora 2A . 3 Growing Native Plants – Short Shrubs . 4 Pocket Guide to Native Plants of Teton County . 6 GLORIA in Wyoming: Beartooth Mtns. and Yellowstone National Park. 6 Halfway Down, Halfway to Go . 8 Desert Yellowhead - One Decade Later By Bonnie Heidel Every plant has a story and some have tomes, if only we could read them start-to-finish! The Desert yellowhead (Yermo xanthocephalus) is the only federally listed plant that is endemic to Wyoming. It was discovered and described by Robert Dorn (Dorn 1991, 2006). Desert yellowhead was listed as Threatened ten years ago (Fish & Wildlife Above: Desert yellowhead (Yermo xanthocephalus) by Jane Service 2002) and critical habitat was designated Dorn. From Dorn (1991). Reprinted with permission from at the one known site not long afterward (Fish & Madroño (California Botanical Society). Wildlife Service 2004). More recently, mining developments in the vicinity have lead to a 20- completed it two years later (Fish & Wildlife year mineral withdrawal and road closures by Service 2010). Subsequently, the Service began the land-managing agency, Bureau of Land to compile information since the time of listing, Management (BLM 2008). called a 5-year review. It was completed and In 2004, a nine-year monitoring saga to posted this fall (Fish & Wildlife Service 2012). annually census the entire population of Desert These reviews revived questions about yellowhead was completed by Richard and species’ habitat requirements and survey Beverly Scott (2009). -

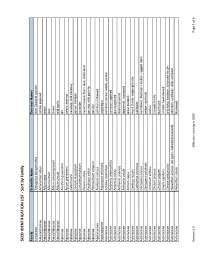

SEED IDENTIFICATION LIST - Sort by Family

SEED IDENTIFICATION LIST - Sort by Family Family Scientific Name Common Names Aizoaceae Tetragonia tetragonoides New Zealand spinach Amaranthaceae Amaranthus albus tumble pigweed Amaryllidaceae Allium cepa onion Amaryllidaceae Allium porrum leek Amaryllidaceae Allium schoenoprasum chives Amaryllidaceae Allium vineale wild garlic Apiaceae Anethum graveolens dill Apiaceae Apium graveolens celery, celeriac Apiaceae Carum carvi caraway; wild caraway Apiaceae Conium maculatum poison hemlock Apiaceae Coriandrum sativum coriander Apiaceae Daucus carota carrot; Queen Ane's lace; wild carrot Apiaceae Pastinaca sativa parsnip; wild parsnip Apiaceae Petroselinum crispum parsley Apocynaceae Asclepias syriaca common milkweed Asparagaceae Asparagus officinalis asparagus Asteraceae Achillea millefolium common yarrow, woolly yarrow Asteraceae Ambrosia artemisiifolia common ragweed Asteraceae Ambrosia trifida giant ragweed Asteraceae Anthemis arvensis field chamomile Asteraceae Anthemis cotula dogfennel, mayweed Asteraceae Arctium lappa great burdock Asteraceae Carduus nutans musk thistle, nodding thistle Asteraceae Carthamus tinctorius safflower Asteraceae Centaurea cyanus cornflower, bachelor's button, ragged robin Asteraceae Centaurea solstitialis yellow starthistle Asteraceae Cichorium endivia endive Asteraceae Cirsium arvense Canada thistle Asteraceae Cirsium vulgare bull thistle Asteraceae Crepis capillaris smooth hawksbeard Asteraceae Cynara cardunculus artichoke, cardoon, artichoke thistle Asteraceae Helianthus annuus (all types, cultivated and -

The Impact of the Flower Mite Aceria Acroptiloni on the Invasive Plant

BioControl (2014) 59:367–375 DOI 10.1007/s10526-014-9573-z The impact of the flower mite Aceria acroptiloni on the invasive plant Russian knapweed, Rhaponticum repens, in its native range Ghorbanali Asadi • Reza Ghorbani • Massimo Cristofaro • Philipp Chetverikov • Radmila Petanovic´ • Biljana Vidovic´ • Urs Schaffner Received: 26 October 2013 / Accepted: 13 March 2014 / Published online: 27 March 2014 Ó International Organization for Biological Control (IOBC) 2014 Abstract Rhaponticum repens (L.) Hidalgo is a clonal field site revealed that A. acroptiloni was by far the Asteraceae plant native to Asia and highly invasive in dominant mite species. We conclude that the mite A. North America. We conducted open-field experiments in acroptiloni is a promising biological control candidate Iran to assess the impact of the biological control inflicting significant impact on the above-ground biomass candidate, Aceria acroptiloni Shevchenko & Kovalev and reproductive output of the invasive plant R. repens. (Acari, Eriophyidae), on the target weed. Using three different experimental approaches, we found that mite Keywords Above-ground biomass Á Acari Á attack reduced the biomass of R. repens shoots by Acroptilon Á Asteraceae Á Classical biological 40–75 %. Except for the initial year of artificial infesta- control Á Pre-release studies Á Seed production tion by A. acroptiloni of R. repens shoots, the number of seed heads was reduced by 60–80 % and the number of seeds by 95–98 %. Morphological investigations of the Introduction mite complex attacking R. repens at the experimental The aim of pre-release studies in classical biological weed control projects is not only to experimentally Handling editor: John Scott. -

Status Report on Desert Yellowhead (Yermo Xanthocephalus)

STATUS REPORT ON DESERT YELLOWHEAD (YERMO XANTHOCEPHALUS) IN WYOMING Illustration by Jane L. Dorn Prepared for the Bureau of Land Management Wyoming State Office and Rawlins District Bonnie Heidel, Botanist Wyoming Natural Diversity Database University of Wyoming P.O. Box 3381 Laramie, WY 82071-3381 30 March 2002 COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT NO. KAA990027 TASK ORDER 4 Acknowledgements Walter Fertig initiated this Yermo xanthocephalus survey and status report update as the original Wyoming Natural Diversity Database (WYNDD) botanist, provided all available WYNDD information resources on the species, and provided comments on the draft of this report. His original status report on the species is reflected throughout. Richard Scott (Central Wyoming College, Fremont County Weed Board) conveyed unpublished data and observations on the species and contributed detailed review of the draft of this report. Robert Dorn (Mountain West) patiently discussed his original work on the species. The Yermo illustration by Jane Dorn is reprinted from the Madrono monograph by Robert Dorn. Jeff Carroll (Bureau of Land Management ) helped secure funding for the project. Frank Blomquist (Bureau of Land Management) provided fieldwork coordination. Connie Breckenridge (Bureau of Land Management) and Mary Jennings (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service) provided opportunities to discuss their technical reports on the species. Scott Laursen (WYNDD) prepared the maps of the species’ location and the model of potential distribution. Jennifer Whipple and Charmaine Refsdal provided copies of their Yermo slides for technical use. Gary Beauvais, Director and WYNDD colleagues provided logistical support. This report is a challenge cost-share project of the Bureau of Land Management and the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database. -

March 2000 Volume 19, No. 1

March 2000 Volume 19, No. 1 In this issue: WNPS News . 2 Botany Briefs Arabis pusilla Dropped from Candidate List . 2 C.L. Porter . 2 New Research Natural Areas . 3 Revolutionary New Taxonomy . 3 On the Germination and Viability of Yermo xanthocephalus akenes . 4 Noteworthy Discoveries . 7 Quotes (John C. Fremont) . 8 Bighorn Native Plant Society . 8 Moonwort (Botrychium lunaria) is one of nearly a dozen species of Botrychium known or reported for Wyoming. It can be recognized by its overlapping, fan-shaped fleshy leaflets and bead- like fertile leaf segments. In Wyoming, moonwort is uncommonly seen in moist meadows forest edges, and alpine scree slopes in the Absaroka, Gros Ventre, Wind River, Bighorn, and Medicine Bow ranges. Moonworts were a specialty of the late Dr. Warren “Herb” Wagner of the University of Michigan, who described 13 of the 30 taxa recognized in the 1993 treatment of the genus in the Flora of North America. Wagner was also famous for unraveling many of the intricacies of hybridization and reticulate evolution in Asplenium and other plants and for conceptual advances in systematics, such as the “Wagner Groundplan- Divergence” method of assessing phylogenetic relationships. Wagner passed away in January at the age of 79. Illustration by Walter Fertig. WNPS NEWS We’re looking for new members: Do you know someone who would be interested in joining WNPS? Scholarship Winners: The WNPS Board is pleased to Send their name or encourage them to contact the announce that three University of Wyoming botany Society for a complimentary newsletter. graduate students have been awarded scholarships for the 1999-2000 academic year. -

ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names 7Th Edition

ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names th 7 Edition ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. M. Schori Published by All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be The Internation Seed Testing Association (ISTA) reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted Zürichstr. 50, CH-8303 Bassersdorf, Switzerland in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior ©2020 International Seed Testing Association (ISTA) permission in writing from ISTA. ISBN 978-3-906549-77-4 ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names 1st Edition 1966 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Prof P. A. Linehan 2nd Edition 1983 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. H. Pirson 3rd Edition 1988 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. W. A. Brandenburg 4th Edition 2001 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 5th Edition 2007 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 6th Edition 2013 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 7th Edition 2019 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. M. Schori 2 7th Edition ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names Content Preface .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Symbols and Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................... -

Alien Plant Species in the Agricultural Habitats of Ukraine: Diversity and Risk Assessment

Ekológia (Bratislava) Vol. 37, No. 1, p. 24–31, 2018 DOI:10.2478/eko-2018-0003 ALIEN PLANT SPECIES IN THE AGRICULTURAL HABITATS OF UKRAINE: DIVERSITY AND RISK ASSESSMENT RAISA BURDA Institute for Evolutionary Ecology, NAS of Ukraine, 37, Lebedeva Str., 03143 Kyiv, Ukraine; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Burda R.: Alien plant species in the agricultural habitats of Ukraine: diversity and risk assessment. Ekológia (Bratislava), Vol. 37, No. 1, p. 24–31, 2018. This paper is the first critical review of the diversity of the Ukrainian adventive flora, which has spread in agricultural habitats in the 21st century. The author’s annotated checklist con- tains the data on 740 species, subspecies and hybrids from 362 genera and 79 families of non-native weeds. The floristic comparative method was used, and the information was gen- eralised into some categories of five characteristic features: climamorphotype (life form), time and method of introduction, level of naturalisation, and distribution into 22 classes of three habitat types according to European Nature Information System (EUNIS). Two assess- ments of the ecological risk of alien plants were first conducted in Ukraine according to the European methods: the risk of overcoming natural migration barriers and the risk of their impact on the environment. The exposed impact of invasive alien plants on ecosystems has a convertible character; the obtained information confirms a high level of phytobiotic contami- nation of agricultural habitats in Ukraine. It is necessary to implement European and national documents regarding the legislative and regulative policy on invasive alien species as one of the threats to biotic diversity. -

Nuclear and Plastid DNA Phylogeny of the Tribe Cardueae (Compositae

1 Nuclear and plastid DNA phylogeny of the tribe Cardueae 2 (Compositae) with Hyb-Seq data: A new subtribal classification and a 3 temporal framework for the origin of the tribe and the subtribes 4 5 Sonia Herrando-Morairaa,*, Juan Antonio Callejab, Mercè Galbany-Casalsb, Núria Garcia-Jacasa, Jian- 6 Quan Liuc, Javier López-Alvaradob, Jordi López-Pujola, Jennifer R. Mandeld, Noemí Montes-Morenoa, 7 Cristina Roquetb,e, Llorenç Sáezb, Alexander Sennikovf, Alfonso Susannaa, Roser Vilatersanaa 8 9 a Botanic Institute of Barcelona (IBB, CSIC-ICUB), Pg. del Migdia, s.n., 08038 Barcelona, Spain 10 b Systematics and Evolution of Vascular Plants (UAB) – Associated Unit to CSIC, Departament de 11 Biologia Animal, Biologia Vegetal i Ecologia, Facultat de Biociències, Universitat Autònoma de 12 Barcelona, ES-08193 Bellaterra, Spain 13 c Key Laboratory for Bio-Resources and Eco-Environment, College of Life Sciences, Sichuan University, 14 Chengdu, China 15 d Department of Biological Sciences, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN 38152, USA 16 e Univ. Grenoble Alpes, Univ. Savoie Mont Blanc, CNRS, LECA (Laboratoire d’Ecologie Alpine), FR- 17 38000 Grenoble, France 18 f Botanical Museum, Finnish Museum of Natural History, PO Box 7, FI-00014 University of Helsinki, 19 Finland; and Herbarium, Komarov Botanical Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences, Prof. Popov str. 20 2, 197376 St. Petersburg, Russia 21 22 *Corresponding author at: Botanic Institute of Barcelona (IBB, CSIC-ICUB), Pg. del Migdia, s. n., ES- 23 08038 Barcelona, Spain. E-mail address: [email protected] (S. Herrando-Moraira). 24 25 Abstract 26 Classification of the tribe Cardueae in natural subtribes has always been a challenge due to the lack of 27 support of some critical branches in previous phylogenies based on traditional Sanger markers. -

Montana Knapweeds

Biology, Ecology and Management of Montana Knapweeds EB0204 revised August 2017 Celestine Duncan, Consultant, Weed Management Services, Helena, MT Jim Story, Research Professor, retired, MSU Western Ag Research Center, Corvallis, MT Roger Sheley, former MSU Extension Weed Specialist, Bozeman, MT revised by Hilary Parkinson, former MSU Research Associate, and Jane Mangold, MSU Extension Invasive Plant Specialist Table of Contents Plant Biology . 3 SpeedyWeed ID . 5 Ecology . 4 Habitat . 4 Spread and Establishment Potential . 6 Damage Potential . 7 Origins, Current Status and Distribution . 8 Management Alternatives . 8 Prevention . 8 Mechanical Control . .9 Cultural Control . .10 Biological Control . .11 Chemical Control . .14 Integrated Weed Management (IWM) . 16 Additional Resources . 17 Acknowledgements . .19 COVER PHOTOS large - spotted knapweed by Marisa Williams, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, bugwood.org top inset - diffuse knapweed by Cindy Roche, bugwood.org bottom inset - Russain knapweed by Steve Dewey, Utah State University, bugwood.org Any mention of products in this publication does not constitute a recommendation by Montana State University Extension. It is a violation of Federal law to use herbicides in a manner inconsistent with their labeling. Copyright © 2017 MSU Extension The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Montana State University and Montana State University Extension prohibit discrimination in all of their programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital and family status. Issued in furtherance of cooperative extension work in agriculture and home economics, acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Jeff Bader, Director of Extension, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT 59717. -

Nigropallidal Encephalomalacia in Horses Grazing Rhaponticum Repens

EQUINE CASE REPORT AND CLINICAL REVIEW Nigropallidal encephalomalacia in horses grazing Rhaponticum repens (creeping knapweed)avj_879 151..154 EQUINE CRB Elliotta* and CI McCowanb treatment options for this disease. Affected horses will die of starva- Nigropallidal encephalomalacia was diagnosed in two horses in tion and dehydration if they are not euthanased. Pathology typically northern Victoria that had a history of long-term pasture access to involves bilaterally symmetrical malacia of the globus pallidus and/or a dense growth of Rhaponticum repens. The region in which the 1–7 affected horses lived had received well above average rainfall for the substantia nigra regions within the thalamus. The only previous several months preceding the poisoning. Affected horses had Australian case was documented in five Spring-drop foals and one sudden onset of subcutaneous oedema of the head, impaired pre- 9-month-old foal with signs of lethargy, inability to graze or drink and hension and mastication, dullness, lethargy and repeated chewing- paresis of the tongue with the lateral edges curling upwards to form an 8 like jaw movements. Diagnosis was confirmed at necropsy, with open tube. characteristic malacic lesions in the substantia nigra and globus The toxin causing equine NPEM remains uncertain. Tyramine and the pallidus of the brain. This is the first documented case of nigro- pallidal encephalomalacia in Australian horses associated with sesquiterpene lactone repin have both been proposed as causative 2,10 R. repens. agents. The characteristics -

2003-2004 Recovery Report to Congress

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Report to Congress on the Recovery of Threatened and Endangered Species Fiscal Years 2003-2004 U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Endangered Species Program www.fws.gov/endangered December 2006 The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is responsible under the Endangered Species Act for conserving and recovering our nation’s rarest plant and animal species and their habitats, working in cooperation with other public and private partners. From the Director Endangered Species Program Contacts Do you want more information on a particular threatened or endangered species or recovery effort near you? Please contact the Regional Office that covers the This 2004 report provides an update on the State(s) you are interested in. If they cannot help you, they will gladly direct you recovery of threatened and endangered species to the nearest Service office. for the period between October 1, 2002, and Region Six — Mountain-Prairie September 30, 2004, and chronicles the progress Washington D.C. Office Region Four — Southeast 134 Union Boulevard, Suite 650 of efforts by the Fish and Wildlife Service and Endangered Species Program 1875 Century Boulevard, Suite 200 Lakewood, CO 80228 the many partners involved in recovery efforts. 4401 N. Fairfax Drive, Room 420 Atlanta, GA 30345 http://mountain-prairie.fws.gov/endspp Arlington, VA 22203 http://www.fws.gov/southeast/es/ During this time, recovery efforts enabled three http://www.fws.gov/endangered Chief, Division of Ecological Services: species to be removed from the Endangered and Chief,