Montana Knapweeds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessing Population Sizes, Biological Potential and Mass

1. ASSESSING POPULATION SIZES, BIOCONTROL POTENTIAL AND MASS PRODUCTION OF THE ROOT BORING MOTH AGAPETA ZOEGANA FOR AREWIDE IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING OF SPOTTED KNAPWEED BIOCONTROL 2. PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATORS: Mark Schwarzländer, PSES Department, University of Idaho, 875 Perimeter DR MS 2339, Moscow, ID 83844-2339, (208) 885-9319, FAX (208)885- 7760, [email protected]; Joseph Milan, USDI Bureau of Land Management, 3948 Development Ave., Boise, ID 83705, (208) 384-3487, FAX (208) 384-3326, [email protected]; Paul Brusven, Nez Perce Tribe Bio-Control Center, P.O. Box 365, 22776 Beaver Road, Lapwai, ID 83540, (208) 843-9374, FAX (208) 843-9373, [email protected] 3. COOPERATORS: Dr. Hariet Hinz (CABI Switzerland), Dr. Urs Schaffner (CABI Switzerland, Dr. Sanford Eigenbrode (University of Idaho), Dr. Heinz Müller-Schärer (University of Fribourg, Switzerland), Brian Marschmann (USDA APHIS PPQ State Director, Idaho), Dr. Rich Hansen (USDA APHIS CPHST, Ft. Collins, Colorado), John (Lewis) Cook (USDI BIA Rocky Mountain Region, Billings, Montana), Dr. John Gaskin (USDA ARS NPARL, Sidney, Montana), Idaho County Weed Superintendents and Idaho-based USFS land managers. BCIP CONTACT: Carol Randall, USFS Northern and Intermountain Regions, 2502 E Sherman Ave, Coeur d'Alene, ID 83814, (208) 769-3051, (208) 769-3062, [email protected] 4. REQUESTED FUNDS: USFS $100,000 (Year 1: $34,000; Year 2: $33,000; and Year 3: $33,000), Project Leveraging: University of Idaho $124,329. 5. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: 1) The current status of ecological research suggests that albeit having some impact on spotted knapweed, both, A. zoegana and C. achates have stronger negative effects on native grasses, thus indirectly benefiting one of most devastating invasive plants in the U.S. -

Long-Term Strategy for Russian Olive and Saltcedar Management

LONG-TERM STRATEGY FOR RUSSIAN OLIVE AND SALTCEDAR MANAGEMENT YELLOWSTONE RIVER CONSERVATION DISTRICT COUNCIL Prepared by Thomas L. Pick, Bozeman, Montana May 1, 2013 Cover photo credit: Tom Pick. Left side: Plains cottonwood seedlings on bar following 2011 runoff. Top: Saltcedar and Russian olive infest the shoreline of the Yellowstone River between Hysham and Forsyth, Montana. Bottom: A healthy narrowleaf cottonwood (Populus angustifolia James) stand adjacent to the channel provides benefits for wildlife and livestock in addition to bank stability and storing floodwater for later release. Table of Contents page number Agreement ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….1 Executive Summary …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….2 Long-Term Strategy for Russian Olive and Saltcedar Management 1.0 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………4 1.1 Biology and Ecology of Russian Olive and Saltcedar ……………………………………………………5 1.12 Russian Olive 1.13 Saltcedar 1.2 Distribution and Spread……………………………………………………………………………………………..6 1.3 Summary of Impacts ………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 1.4 Legal Framework ……………………………………………………………………………………………………….7 2.0 Strategic Management Objective and Goals ………………………………………………………………..…..8 2.1 Goal 1: Prevent New Infestations (Control Spread) …………………………………….……….……8 2.2 Goal 2: Eradicate All Infestations Within the River Corridor ………………………………………9 2.3 Goal 3: Manage Populations Outside of the River Corridor ……………………………………….9 3.0 Treatment Strategies and Priorities …………………………………….……………………………………………9 -

Spotted Knapweed Centaurea Stoebe Ssp. Micranthos (Gugler) Hayek

spotted knapweed Centaurea stoebe ssp. micranthos (Gugler) Hayek Synonyms: Acosta maculosa auct. non Holub, Centaurea biebersteinii DC., C. maculosa auct. non Lam, C. maculosa ssp. micranthos G. Gmelin ex Gugler Other common names: None Family: Asteraceae Invasiveness Rank: 86 The invasiveness rank is calculated based on a species’ ecological impacts, biological attributes, distribution, and response to control measures. The ranks are scaled from 0 to 100, with 0 representing a plant that poses no threat to native ecosystems and 100 representing a plant that poses a major threat to native ecosystems. Description Ecological Impact Spotted knapweed is a biennial to short-lived perennial Impact on community composition, structure, and plant. Stems are 30½ to 91 cm tall and generally interactions: Spotted knapweed often forms dense branched. Rosette leaves are compound with several stands in natural communities. Infestations reduce the irregularly lobed segments. Stem leaves are alternate, 5 vigor of native plants, decrease the species diversity of to 15 cm long, more or less hairy, and resin-dotted. plant communities, and degrade the forage quality of Lower stem leaves are narrowly divided, while the wildlife habitats. Winter-ranging elk may avoid foraging upper stem leaves are undivided. Flower heads are 19 to in spotted knapweed dominated communities (Rice et al. 25½ mm wide and are composed of purple disc florets 1997). Knapweeds are allelopathic, inhibiting the (Royer and Dickinson 1999, Whitson et al. 2000). establishment and growth of surrounding vegetation (Whitson et al. 2000). Impact on ecosystem processes: Infestations of spotted knapweed have been shown to increase the erosion of topsoil. -

Influence of Seed Head–Attacking Biological Control Agents

BIOLOGICAL CONTROLÑWEEDS Influence of Seed Head–Attacking Biological Control Agents on Spotted Knapweed Reproductive Potential in Western Montana Over a 30-Year Period 1,2 3 1 1 JIM M. STORY, LINCOLN SMITH, JANELLE G. CORN, AND LINDA J. WHITE Environ. Entomol. 37(2): 510Ð519 (2008) ABSTRACT Five insect biological control agents that attack ßower heads of spotted knapweed, Centaurea stoebe L. subsp. micranthos (Gugler) Hayek, became established in western Montana between 1973 and 1992. In a controlled Þeld experiment in 2006, seed-head insects reduced spotted knapweed seed production per seed head by 84.4%. The seed production at two sites in western Montana where these biological control agents were well established was 91.6Ð93.8% lower in 2004Ð2005 than 1974Ð1975, whereas the number of seed heads per square meter was 70.7% lower, and the reproductive potential (seeds/m2) was 95.9Ð99.0% lower. The average seed bank in 2005 at four sites containing robust spotted knapweed populations was 281 seeds/m2 compared with 19 seeds/m2 at four sites where knapweed density has declined. Seed bank densities were much higher at sites in central Montana (4,218 seeds/m2), where the insects have been established for a shorter period. Urophora affinis Frauenfeld was the most abundant species at eight study sites, infesting 66.7% of the seed heads, followed by a 47.3% infestation by Larinus minutus Gyllenhal and L. obtusus Gyllenhal. From 1974 to 1985, Urophora spp. apparently reduced the number of seeds per seed head by 34.5Ð46.9%; the addition of Larinus spp. further reduced seed numbers 84.2Ð90.5% by 2005. -

Native Plant Establishment Success Influenced Yb Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea Stoebe) Control Method

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Funded Articles Open Access Publishing Support Fund 2014 Native Plant Establishment Success Influenced yb Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea stoebe) Control Method Laurelin M. Martin Grand Valley State University Neil W. MacDonald Grand Valley State University, [email protected] Tami E. Brown Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/oapsf_articles Part of the Biology Commons ScholarWorks Citation Martin, Laurelin M.; MacDonald, Neil W.; and Brown, Tami E., "Native Plant Establishment Success Influenced by Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea stoebe) Control Method" (2014). Funded Articles. 15. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/oapsf_articles/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Publishing Support Fund at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Funded Articles by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESEARCH ARTICLE Native Plant Establishment Success Influenced by Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea stoebe) Control Method Laurelin M. Martin, Neil W. MacDonald and Tami E. Brown ABSTRACT Invasive species frequently need to be controlled as part of efforts to reestablish native species on degraded sites. While the effectiveness of differing control methods are often reported, the impacts these methods have on the establishment of a native plant community are often unknown. To determine methods that effectively reduce spotted knapweed (Cen- taurea stoebe) while enhancing native species establishment, we tested 12 treatment combinations consisting of an initial site preparation (mowing, mowing + clopyralid, or mowing + glyphosate), in factorial combination with annual adult knapweed hand pulling and/or burning. We established 48 plots and applied site preparation treatments during summer 2008, seeded 23 native forbs and grasses during spring 2009, pulled adult knapweed annually from 2009–2012, and burned in the early spring 2012. -

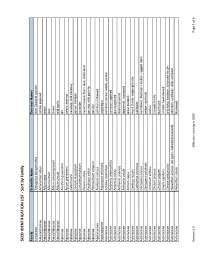

SEED IDENTIFICATION LIST - Sort by Family

SEED IDENTIFICATION LIST - Sort by Family Family Scientific Name Common Names Aizoaceae Tetragonia tetragonoides New Zealand spinach Amaranthaceae Amaranthus albus tumble pigweed Amaryllidaceae Allium cepa onion Amaryllidaceae Allium porrum leek Amaryllidaceae Allium schoenoprasum chives Amaryllidaceae Allium vineale wild garlic Apiaceae Anethum graveolens dill Apiaceae Apium graveolens celery, celeriac Apiaceae Carum carvi caraway; wild caraway Apiaceae Conium maculatum poison hemlock Apiaceae Coriandrum sativum coriander Apiaceae Daucus carota carrot; Queen Ane's lace; wild carrot Apiaceae Pastinaca sativa parsnip; wild parsnip Apiaceae Petroselinum crispum parsley Apocynaceae Asclepias syriaca common milkweed Asparagaceae Asparagus officinalis asparagus Asteraceae Achillea millefolium common yarrow, woolly yarrow Asteraceae Ambrosia artemisiifolia common ragweed Asteraceae Ambrosia trifida giant ragweed Asteraceae Anthemis arvensis field chamomile Asteraceae Anthemis cotula dogfennel, mayweed Asteraceae Arctium lappa great burdock Asteraceae Carduus nutans musk thistle, nodding thistle Asteraceae Carthamus tinctorius safflower Asteraceae Centaurea cyanus cornflower, bachelor's button, ragged robin Asteraceae Centaurea solstitialis yellow starthistle Asteraceae Cichorium endivia endive Asteraceae Cirsium arvense Canada thistle Asteraceae Cirsium vulgare bull thistle Asteraceae Crepis capillaris smooth hawksbeard Asteraceae Cynara cardunculus artichoke, cardoon, artichoke thistle Asteraceae Helianthus annuus (all types, cultivated and -

The Impact of the Flower Mite Aceria Acroptiloni on the Invasive Plant

BioControl (2014) 59:367–375 DOI 10.1007/s10526-014-9573-z The impact of the flower mite Aceria acroptiloni on the invasive plant Russian knapweed, Rhaponticum repens, in its native range Ghorbanali Asadi • Reza Ghorbani • Massimo Cristofaro • Philipp Chetverikov • Radmila Petanovic´ • Biljana Vidovic´ • Urs Schaffner Received: 26 October 2013 / Accepted: 13 March 2014 / Published online: 27 March 2014 Ó International Organization for Biological Control (IOBC) 2014 Abstract Rhaponticum repens (L.) Hidalgo is a clonal field site revealed that A. acroptiloni was by far the Asteraceae plant native to Asia and highly invasive in dominant mite species. We conclude that the mite A. North America. We conducted open-field experiments in acroptiloni is a promising biological control candidate Iran to assess the impact of the biological control inflicting significant impact on the above-ground biomass candidate, Aceria acroptiloni Shevchenko & Kovalev and reproductive output of the invasive plant R. repens. (Acari, Eriophyidae), on the target weed. Using three different experimental approaches, we found that mite Keywords Above-ground biomass Á Acari Á attack reduced the biomass of R. repens shoots by Acroptilon Á Asteraceae Á Classical biological 40–75 %. Except for the initial year of artificial infesta- control Á Pre-release studies Á Seed production tion by A. acroptiloni of R. repens shoots, the number of seed heads was reduced by 60–80 % and the number of seeds by 95–98 %. Morphological investigations of the Introduction mite complex attacking R. repens at the experimental The aim of pre-release studies in classical biological weed control projects is not only to experimentally Handling editor: John Scott. -

Russian Knapweed in the Southwest

United States Department of Agriculture Field Guide for Managing Russian Knapweed in the Southwest Forest Southwestern Service Region TP-R3-16-13 February 2015 Cover Photos Upper left: Steve Dewey, Utah State University, Bugwood.org Upper right: Steve Dewey, Utah State University, Bugwood.org Bottom center: Steve Dewey, Utah State University, Bugwood.org The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Printed on recycled paper Russian knapweed (Rhaponticum repens L., formerly Acroptilon repens L. Sunflower family (Asteraceae) Russian knapweed is an invasive plant that has been listed cloned plants. Also produces seed (50 to 500 seeds as a noxious weed in Arizona and New Mexico. This field per plant; viable for 2 to 3 years). guide serves as the U.S. Forest Service’s recommendations • Releases allelopathic chemicals that can inhibit for management of Russian knapweed in forests, growth of other plants; contains sesquiterpene woodlands, and rangelands associated with its Southwestern lactones that are toxic to horses. -

Checklist of the Vascular Alien Flora of Catalonia (Northeastern Iberian Peninsula, Spain) Pere Aymerich1 & Llorenç Sáez2,3

BOTANICAL CHECKLISTS Mediterranean Botany ISSNe 2603-9109 https://dx.doi.org/10.5209/mbot.63608 Checklist of the vascular alien flora of Catalonia (northeastern Iberian Peninsula, Spain) Pere Aymerich1 & Llorenç Sáez2,3 Received: 7 March 2019 / Accepted: 28 June 2019 / Published online: 7 November 2019 Abstract. This is an inventory of the vascular alien flora of Catalonia (northeastern Iberian Peninsula, Spain) updated to 2018, representing 1068 alien taxa in total. 554 (52.0%) out of them are casual and 514 (48.0%) are established. 87 taxa (8.1% of the total number and 16.8 % of those established) show an invasive behaviour. The geographic zone with more alien plants is the most anthropogenic maritime area. However, the differences among regions decrease when the degree of naturalization of taxa increases and the number of invaders is very similar in all sectors. Only 26.2% of the taxa are more or less abundant, while the rest are rare or they have vanished. The alien flora is represented by 115 families, 87 out of them include naturalised species. The most diverse genera are Opuntia (20 taxa), Amaranthus (18 taxa) and Solanum (15 taxa). Most of the alien plants have been introduced since the beginning of the twentieth century (70.7%), with a strong increase since 1970 (50.3% of the total number). Almost two thirds of alien taxa have their origin in Euro-Mediterranean area and America, while 24.6% come from other geographical areas. The taxa originated in cultivation represent 9.5%, whereas spontaneous hybrids only 1.2%. From the temporal point of view, the rate of Euro-Mediterranean taxa shows a progressive reduction parallel to an increase of those of other origins, which have reached 73.2% of introductions during the last 50 years. -

Multi-Trophic Level Interactions Between the Invasive Plant

MULTI-TROPHIC LEVEL INTERACTIONS BETWEEN THE INVASIVE PLANT CENTAUREA STOEBE, INSECTS AND NATIVE PLANTS by Christina Rachel Herron-Sweet A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Land Resources and Environmental Sciences MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana May 2014 ©COPYRIGHT by Christina Rachel Herron-Sweet 2014 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION To my parents and grandparents, who instilled in me the value of education and have been my biggest supporters along the way. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks go to my two advisers Drs. Jane Mangold and Erik Lehnhoff for all their tremendous support, advice and feedback during my graduate program. My two other committee members Drs. Laura Burkle and Jeff Littlefield also deserve a huge thank you for the time and effort they put into helping me with various aspects of my project. This research would not have been possible without the dedicated crew of field and lab helpers: Torrin Daniels, Darcy Goodson, Daniel France, James Collins, Ann de Meij, Noelle Orloff, Krista Ehlert, and Hally Berg. The following individuals deserve recognition for their patience in teaching me pollinator identification, and for providing parasitoid identifications: Casey Delphia, Mike Simanonok, Justin Runyon, Charles Hart, Stacy Davis, Mike Ivie, Roger Burks, Jim Woolley, David Wahl, Steve Heydon, and Gary Gibson. Hilary Parkinson and Matt Lavin also offered their expertise in plant identification. Statistical advice and R code was generously offered by Megan Higgs, Sean McKenzie, Pamela Santibanez, Dan Bachen, Michael Lerch, Michael Simanonok, Zach Miller and Dave Roberts. Bryce Christiaens, Lyn Huyser, Gil Gale and Craig Campbell provided instrumental consultation on locating field sites, and the Circle H Ranch, Flying D Ranch and the United States Forest Service graciously allowed this research to take place on their property. -

Thistle Identification Referee 2017

Thistle Identification Referee 2017 Welcome to the Thistle Identification Referee. The purpose of the referee is to review morphological characters that are useful for identification of thistle and knapweed fruits, as well as review useful resources for making decisions on identification and classification of species as noxious weed seeds. Using the Identification Guide for Some Common and Noxious Thistle and Knapweed Fruits (Meyer 2017) and other references of your choosing, please answer the questions below (most are multiple choice). Use the last page of this document as your answer sheet for the questions. Please send your answer sheet to Deborah Meyer via email ([email protected]) by May 26, 2017. Be sure to fill in your name, lab name, and email address on the answer sheet to receive CE credit. 1. In the Asteraceae, the pappus represents this floral structure: a. Modified stigma b. Modified corolla c. Modified calyx d. Modified perianth 2. Which of the following species has an epappose fruit? a. Centaurea calcitrapa b. Cirsium vulgare c. Onopordum acaulon d. Cynara cardunculus 3. Which of the following genera has a pappus comprised of plumose bristles? a. Centaurea b. Carduus c. Silybum d. Cirsium 4. Which of the following species has the largest fruits? a. Cirsium arvense b. Cirsium japonicum c. Cirsium undulatum d. Cirsium vulgare 5. Which of the following species has a pappus that hides the style base? a. Volutaria muricata b. Mantisalca salmantica c. Centaurea solstitialis d. Crupina vulgaris 6. Which of the following species is classified as a noxious weed seed somewhere in the United States? a. -

TORTS Newsletter of the Troop of Reputed Tortricid Systematists

Volume 6 13 July 2005 Issue 2 TORTS Newsletter of the Troop of Reputed Tortricid Systematists TORTRICIDAE OF TAIWAN “I ELEN” MEETING IN NOW ON-LINE CAMPINAS, BRAZIL According to Shen-Horn Yen, the on-line I ELEN (I Encontro Sobre Lepidoptera checklist of the Lepidoptera of Taiwan has been Neotropicais), roughly translated as the “First uploaded to the "Taiwan Biodiversity Meeting On The Neotropical Lepidoptera,” was Information Network" (http://taibnet.sinica. held in Campinas, Brazil, 17-21 April 2005. edu.tw/english/home.htm). A recently revised Hosted and organized by two Brazilian and updated checklist of the Tortricidae of lepidopterists, Andre Victor Lucci Freitas and Taiwan can be found there. The literature and Marcelo Duarte, the meeting was attended by image databases are still under construction, over 200 Lepidoptera enthusiasts, primarily and Shen-Horn indicates that those will be Latin Americans, over half of which were completed within about 2 years. students. The large number of young people _____________________________________ was in stark contrast to most North American Lepidoptera meetings in which the crowd is TORTRICID CATALOG dominated by geriatric (or nearly geriatric, as in my case) professionals, with student AVAILABLE FROM participation about 20-30%. Among the APOLLO BOOKS attendees were about 8-10 North Americans and about 5-6 Europeans, with the remainder of the World Catalogue of Insects, Volume 5, audience and presenters from Central and South Lepidoptera, Tortricidae is now available from America, with nearly every Latin American Apollo Books. The catalog treats over 9,100 country represented by one or more participants. valid species and over 15,000 names; it is 741 The talks, presented mostly in Portuguese pages in length.