Nigropallidal Encephalomalacia in Horses Grazing Rhaponticum Repens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long-Term Strategy for Russian Olive and Saltcedar Management

LONG-TERM STRATEGY FOR RUSSIAN OLIVE AND SALTCEDAR MANAGEMENT YELLOWSTONE RIVER CONSERVATION DISTRICT COUNCIL Prepared by Thomas L. Pick, Bozeman, Montana May 1, 2013 Cover photo credit: Tom Pick. Left side: Plains cottonwood seedlings on bar following 2011 runoff. Top: Saltcedar and Russian olive infest the shoreline of the Yellowstone River between Hysham and Forsyth, Montana. Bottom: A healthy narrowleaf cottonwood (Populus angustifolia James) stand adjacent to the channel provides benefits for wildlife and livestock in addition to bank stability and storing floodwater for later release. Table of Contents page number Agreement ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….1 Executive Summary …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….2 Long-Term Strategy for Russian Olive and Saltcedar Management 1.0 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………4 1.1 Biology and Ecology of Russian Olive and Saltcedar ……………………………………………………5 1.12 Russian Olive 1.13 Saltcedar 1.2 Distribution and Spread……………………………………………………………………………………………..6 1.3 Summary of Impacts ………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 1.4 Legal Framework ……………………………………………………………………………………………………….7 2.0 Strategic Management Objective and Goals ………………………………………………………………..…..8 2.1 Goal 1: Prevent New Infestations (Control Spread) …………………………………….……….……8 2.2 Goal 2: Eradicate All Infestations Within the River Corridor ………………………………………9 2.3 Goal 3: Manage Populations Outside of the River Corridor ……………………………………….9 3.0 Treatment Strategies and Priorities …………………………………….……………………………………………9 -

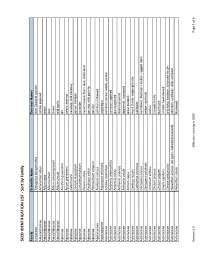

SEED IDENTIFICATION LIST - Sort by Family

SEED IDENTIFICATION LIST - Sort by Family Family Scientific Name Common Names Aizoaceae Tetragonia tetragonoides New Zealand spinach Amaranthaceae Amaranthus albus tumble pigweed Amaryllidaceae Allium cepa onion Amaryllidaceae Allium porrum leek Amaryllidaceae Allium schoenoprasum chives Amaryllidaceae Allium vineale wild garlic Apiaceae Anethum graveolens dill Apiaceae Apium graveolens celery, celeriac Apiaceae Carum carvi caraway; wild caraway Apiaceae Conium maculatum poison hemlock Apiaceae Coriandrum sativum coriander Apiaceae Daucus carota carrot; Queen Ane's lace; wild carrot Apiaceae Pastinaca sativa parsnip; wild parsnip Apiaceae Petroselinum crispum parsley Apocynaceae Asclepias syriaca common milkweed Asparagaceae Asparagus officinalis asparagus Asteraceae Achillea millefolium common yarrow, woolly yarrow Asteraceae Ambrosia artemisiifolia common ragweed Asteraceae Ambrosia trifida giant ragweed Asteraceae Anthemis arvensis field chamomile Asteraceae Anthemis cotula dogfennel, mayweed Asteraceae Arctium lappa great burdock Asteraceae Carduus nutans musk thistle, nodding thistle Asteraceae Carthamus tinctorius safflower Asteraceae Centaurea cyanus cornflower, bachelor's button, ragged robin Asteraceae Centaurea solstitialis yellow starthistle Asteraceae Cichorium endivia endive Asteraceae Cirsium arvense Canada thistle Asteraceae Cirsium vulgare bull thistle Asteraceae Crepis capillaris smooth hawksbeard Asteraceae Cynara cardunculus artichoke, cardoon, artichoke thistle Asteraceae Helianthus annuus (all types, cultivated and -

The Impact of the Flower Mite Aceria Acroptiloni on the Invasive Plant

BioControl (2014) 59:367–375 DOI 10.1007/s10526-014-9573-z The impact of the flower mite Aceria acroptiloni on the invasive plant Russian knapweed, Rhaponticum repens, in its native range Ghorbanali Asadi • Reza Ghorbani • Massimo Cristofaro • Philipp Chetverikov • Radmila Petanovic´ • Biljana Vidovic´ • Urs Schaffner Received: 26 October 2013 / Accepted: 13 March 2014 / Published online: 27 March 2014 Ó International Organization for Biological Control (IOBC) 2014 Abstract Rhaponticum repens (L.) Hidalgo is a clonal field site revealed that A. acroptiloni was by far the Asteraceae plant native to Asia and highly invasive in dominant mite species. We conclude that the mite A. North America. We conducted open-field experiments in acroptiloni is a promising biological control candidate Iran to assess the impact of the biological control inflicting significant impact on the above-ground biomass candidate, Aceria acroptiloni Shevchenko & Kovalev and reproductive output of the invasive plant R. repens. (Acari, Eriophyidae), on the target weed. Using three different experimental approaches, we found that mite Keywords Above-ground biomass Á Acari Á attack reduced the biomass of R. repens shoots by Acroptilon Á Asteraceae Á Classical biological 40–75 %. Except for the initial year of artificial infesta- control Á Pre-release studies Á Seed production tion by A. acroptiloni of R. repens shoots, the number of seed heads was reduced by 60–80 % and the number of seeds by 95–98 %. Morphological investigations of the Introduction mite complex attacking R. repens at the experimental The aim of pre-release studies in classical biological weed control projects is not only to experimentally Handling editor: John Scott. -

Russian Knapweed in the Southwest

United States Department of Agriculture Field Guide for Managing Russian Knapweed in the Southwest Forest Southwestern Service Region TP-R3-16-13 February 2015 Cover Photos Upper left: Steve Dewey, Utah State University, Bugwood.org Upper right: Steve Dewey, Utah State University, Bugwood.org Bottom center: Steve Dewey, Utah State University, Bugwood.org The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Printed on recycled paper Russian knapweed (Rhaponticum repens L., formerly Acroptilon repens L. Sunflower family (Asteraceae) Russian knapweed is an invasive plant that has been listed cloned plants. Also produces seed (50 to 500 seeds as a noxious weed in Arizona and New Mexico. This field per plant; viable for 2 to 3 years). guide serves as the U.S. Forest Service’s recommendations • Releases allelopathic chemicals that can inhibit for management of Russian knapweed in forests, growth of other plants; contains sesquiterpene woodlands, and rangelands associated with its Southwestern lactones that are toxic to horses. -

Checklist of the Vascular Alien Flora of Catalonia (Northeastern Iberian Peninsula, Spain) Pere Aymerich1 & Llorenç Sáez2,3

BOTANICAL CHECKLISTS Mediterranean Botany ISSNe 2603-9109 https://dx.doi.org/10.5209/mbot.63608 Checklist of the vascular alien flora of Catalonia (northeastern Iberian Peninsula, Spain) Pere Aymerich1 & Llorenç Sáez2,3 Received: 7 March 2019 / Accepted: 28 June 2019 / Published online: 7 November 2019 Abstract. This is an inventory of the vascular alien flora of Catalonia (northeastern Iberian Peninsula, Spain) updated to 2018, representing 1068 alien taxa in total. 554 (52.0%) out of them are casual and 514 (48.0%) are established. 87 taxa (8.1% of the total number and 16.8 % of those established) show an invasive behaviour. The geographic zone with more alien plants is the most anthropogenic maritime area. However, the differences among regions decrease when the degree of naturalization of taxa increases and the number of invaders is very similar in all sectors. Only 26.2% of the taxa are more or less abundant, while the rest are rare or they have vanished. The alien flora is represented by 115 families, 87 out of them include naturalised species. The most diverse genera are Opuntia (20 taxa), Amaranthus (18 taxa) and Solanum (15 taxa). Most of the alien plants have been introduced since the beginning of the twentieth century (70.7%), with a strong increase since 1970 (50.3% of the total number). Almost two thirds of alien taxa have their origin in Euro-Mediterranean area and America, while 24.6% come from other geographical areas. The taxa originated in cultivation represent 9.5%, whereas spontaneous hybrids only 1.2%. From the temporal point of view, the rate of Euro-Mediterranean taxa shows a progressive reduction parallel to an increase of those of other origins, which have reached 73.2% of introductions during the last 50 years. -

ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names 7Th Edition

ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names th 7 Edition ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. M. Schori Published by All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be The Internation Seed Testing Association (ISTA) reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted Zürichstr. 50, CH-8303 Bassersdorf, Switzerland in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior ©2020 International Seed Testing Association (ISTA) permission in writing from ISTA. ISBN 978-3-906549-77-4 ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names 1st Edition 1966 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Prof P. A. Linehan 2nd Edition 1983 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. H. Pirson 3rd Edition 1988 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. W. A. Brandenburg 4th Edition 2001 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 5th Edition 2007 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 6th Edition 2013 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 7th Edition 2019 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. M. Schori 2 7th Edition ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names Content Preface .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Symbols and Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................... -

Thistle Identification Referee 2017

Thistle Identification Referee 2017 Welcome to the Thistle Identification Referee. The purpose of the referee is to review morphological characters that are useful for identification of thistle and knapweed fruits, as well as review useful resources for making decisions on identification and classification of species as noxious weed seeds. Using the Identification Guide for Some Common and Noxious Thistle and Knapweed Fruits (Meyer 2017) and other references of your choosing, please answer the questions below (most are multiple choice). Use the last page of this document as your answer sheet for the questions. Please send your answer sheet to Deborah Meyer via email ([email protected]) by May 26, 2017. Be sure to fill in your name, lab name, and email address on the answer sheet to receive CE credit. 1. In the Asteraceae, the pappus represents this floral structure: a. Modified stigma b. Modified corolla c. Modified calyx d. Modified perianth 2. Which of the following species has an epappose fruit? a. Centaurea calcitrapa b. Cirsium vulgare c. Onopordum acaulon d. Cynara cardunculus 3. Which of the following genera has a pappus comprised of plumose bristles? a. Centaurea b. Carduus c. Silybum d. Cirsium 4. Which of the following species has the largest fruits? a. Cirsium arvense b. Cirsium japonicum c. Cirsium undulatum d. Cirsium vulgare 5. Which of the following species has a pappus that hides the style base? a. Volutaria muricata b. Mantisalca salmantica c. Centaurea solstitialis d. Crupina vulgaris 6. Which of the following species is classified as a noxious weed seed somewhere in the United States? a. -

Alien Plant Species in the Agricultural Habitats of Ukraine: Diversity and Risk Assessment

Ekológia (Bratislava) Vol. 37, No. 1, p. 24–31, 2018 DOI:10.2478/eko-2018-0003 ALIEN PLANT SPECIES IN THE AGRICULTURAL HABITATS OF UKRAINE: DIVERSITY AND RISK ASSESSMENT RAISA BURDA Institute for Evolutionary Ecology, NAS of Ukraine, 37, Lebedeva Str., 03143 Kyiv, Ukraine; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Burda R.: Alien plant species in the agricultural habitats of Ukraine: diversity and risk assessment. Ekológia (Bratislava), Vol. 37, No. 1, p. 24–31, 2018. This paper is the first critical review of the diversity of the Ukrainian adventive flora, which has spread in agricultural habitats in the 21st century. The author’s annotated checklist con- tains the data on 740 species, subspecies and hybrids from 362 genera and 79 families of non-native weeds. The floristic comparative method was used, and the information was gen- eralised into some categories of five characteristic features: climamorphotype (life form), time and method of introduction, level of naturalisation, and distribution into 22 classes of three habitat types according to European Nature Information System (EUNIS). Two assess- ments of the ecological risk of alien plants were first conducted in Ukraine according to the European methods: the risk of overcoming natural migration barriers and the risk of their impact on the environment. The exposed impact of invasive alien plants on ecosystems has a convertible character; the obtained information confirms a high level of phytobiotic contami- nation of agricultural habitats in Ukraine. It is necessary to implement European and national documents regarding the legislative and regulative policy on invasive alien species as one of the threats to biotic diversity. -

Nuclear and Plastid DNA Phylogeny of the Tribe Cardueae (Compositae

1 Nuclear and plastid DNA phylogeny of the tribe Cardueae 2 (Compositae) with Hyb-Seq data: A new subtribal classification and a 3 temporal framework for the origin of the tribe and the subtribes 4 5 Sonia Herrando-Morairaa,*, Juan Antonio Callejab, Mercè Galbany-Casalsb, Núria Garcia-Jacasa, Jian- 6 Quan Liuc, Javier López-Alvaradob, Jordi López-Pujola, Jennifer R. Mandeld, Noemí Montes-Morenoa, 7 Cristina Roquetb,e, Llorenç Sáezb, Alexander Sennikovf, Alfonso Susannaa, Roser Vilatersanaa 8 9 a Botanic Institute of Barcelona (IBB, CSIC-ICUB), Pg. del Migdia, s.n., 08038 Barcelona, Spain 10 b Systematics and Evolution of Vascular Plants (UAB) – Associated Unit to CSIC, Departament de 11 Biologia Animal, Biologia Vegetal i Ecologia, Facultat de Biociències, Universitat Autònoma de 12 Barcelona, ES-08193 Bellaterra, Spain 13 c Key Laboratory for Bio-Resources and Eco-Environment, College of Life Sciences, Sichuan University, 14 Chengdu, China 15 d Department of Biological Sciences, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN 38152, USA 16 e Univ. Grenoble Alpes, Univ. Savoie Mont Blanc, CNRS, LECA (Laboratoire d’Ecologie Alpine), FR- 17 38000 Grenoble, France 18 f Botanical Museum, Finnish Museum of Natural History, PO Box 7, FI-00014 University of Helsinki, 19 Finland; and Herbarium, Komarov Botanical Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences, Prof. Popov str. 20 2, 197376 St. Petersburg, Russia 21 22 *Corresponding author at: Botanic Institute of Barcelona (IBB, CSIC-ICUB), Pg. del Migdia, s. n., ES- 23 08038 Barcelona, Spain. E-mail address: [email protected] (S. Herrando-Moraira). 24 25 Abstract 26 Classification of the tribe Cardueae in natural subtribes has always been a challenge due to the lack of 27 support of some critical branches in previous phylogenies based on traditional Sanger markers. -

Montana Knapweeds

Biology, Ecology and Management of Montana Knapweeds EB0204 revised August 2017 Celestine Duncan, Consultant, Weed Management Services, Helena, MT Jim Story, Research Professor, retired, MSU Western Ag Research Center, Corvallis, MT Roger Sheley, former MSU Extension Weed Specialist, Bozeman, MT revised by Hilary Parkinson, former MSU Research Associate, and Jane Mangold, MSU Extension Invasive Plant Specialist Table of Contents Plant Biology . 3 SpeedyWeed ID . 5 Ecology . 4 Habitat . 4 Spread and Establishment Potential . 6 Damage Potential . 7 Origins, Current Status and Distribution . 8 Management Alternatives . 8 Prevention . 8 Mechanical Control . .9 Cultural Control . .10 Biological Control . .11 Chemical Control . .14 Integrated Weed Management (IWM) . 16 Additional Resources . 17 Acknowledgements . .19 COVER PHOTOS large - spotted knapweed by Marisa Williams, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, bugwood.org top inset - diffuse knapweed by Cindy Roche, bugwood.org bottom inset - Russain knapweed by Steve Dewey, Utah State University, bugwood.org Any mention of products in this publication does not constitute a recommendation by Montana State University Extension. It is a violation of Federal law to use herbicides in a manner inconsistent with their labeling. Copyright © 2017 MSU Extension The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Montana State University and Montana State University Extension prohibit discrimination in all of their programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital and family status. Issued in furtherance of cooperative extension work in agriculture and home economics, acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Jeff Bader, Director of Extension, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT 59717. -

Sustainable Sourcing : Markets for Certified Chinese

SUSTAINABLE SOURCING: MARKETS FOR CERTIFIED CHINESE MEDICINAL AND AROMATIC PLANTS In collaboration with SUSTAINABLE SOURCING: MARKETS FOR CERTIFIED CHINESE MEDICINAL AND AROMATIC PLANTS SUSTAINABLE SOURCING: MARKETS FOR CERTIFIED CHINESE MEDICINAL AND AROMATIC PLANTS Abstract for trade information services ID=43163 2016 SITC-292.4 SUS International Trade Centre (ITC) Sustainable Sourcing: Markets for Certified Chinese Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Geneva: ITC, 2016. xvi, 141 pages (Technical paper) Doc. No. SC-2016-5.E This study on the market potential of sustainably wild-collected botanical ingredients originating from the People’s Republic of China with fair and organic certifications provides an overview of current export trade in both wild-collected and cultivated botanical, algal and fungal ingredients from China, market segments such as the fair trade and organic sectors, and the market trends for certified ingredients. It also investigates which international standards would be the most appropriate and applicable to the special case of China in consideration of its biodiversity conservation efforts in traditional wild collection communities and regions, and includes bibliographical references (pp. 139–140). Descriptors: Medicinal Plants, Spices, Certification, Organic Products, Fair Trade, China, Market Research English For further information on this technical paper, contact Mr. Alexander Kasterine ([email protected]) The International Trade Centre (ITC) is the joint agency of the World Trade Organization and the United Nations. ITC, Palais des Nations, 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland (www.intracen.org) Suggested citation: International Trade Centre (2016). Sustainable Sourcing: Markets for Certified Chinese Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, International Trade Centre, Geneva, Switzerland. This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. -

Antimicrobial Activity of Rhaponticum Acaule and Scorzonera Undulata Growing Wild in Tunisia

African Journal of Microbiology Research Vol. 4(19) pp. 1954-1958, 4 October, 2010 Available online http://www.academicjournals.org/ajmr ISSN 1996-0808 ©2010 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Antimicrobial activity of Rhaponticum acaule and Scorzonera undulata growing wild in Tunisia Houda Ben Abdelkader1*, Karima Bel Haj Salah2, Kaouthar Liouane1, Olfa Boussaada3, Karima Gafsi1, Mohamed Ali Mahjoub1, Mahjoub Aouni2, Ahmed Nourreddine Hellal3 and Zine Mighri1 1Laboratory of Natural Substances, Chemistry and Organic Synthesis, Faculty of Science, 5000 Monastir, Tunisia (99/UR/12-26). 2Laboratory of Transmissible Diseases and Biologically Active Substances, Faculty of Pharmacy, 5000 Monastir, Tunisia. 3Laboratory of Conservation and Valorisation of Plant Resources, Faculty of Pharmacy, 5000 Monastir, Tunisia. Accepted 3 August, 2010 This study examined the in vitro antibacterial and antifungal activities of the extracts (butanolic, ethyl acetate, petroleum ether and the product H2) of 2 plants belonging to the Asteraceae family: Rhaponticum acaule L. and Scorzonera undulata L. Butanolic and ethyl acetate extracts of the Rhaponticum acaule plant showed a moderate antibacterial activity against 3 of the tested strains; Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli and Enterococcus fecalis while Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Citrobacter freundeï were resistant to the extracts. The product H2 showed an antibacterial activity against S. aureus, C. freundeï and E. fecalis. From the results of the antifungal activity, we observed that butanolic and ethyl acetate extracts of R. acaule showed a strong inhibition against Trichophyton rubrum with inhibition percentage of 56.25 and 78.75%, respectively. Butanolic extract showed a moderate inhibition of Microsporum canis, Scopulariopsis brevicaulis and Aspergillus fumigatus while ethyl acetate extract showed low inhibition.