Justin's Epitome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

341 BC the THIRD PHILIPPIC Demosthenes Translated By

1 341 BC THE THIRD PHILIPPIC Demosthenes translated by Thomas Leland, D.D. Notes and Introduction by Thomas Leland, D.D. 2 Demosthenes (383-322 BC) - Athenian statesman and the most famous of Greek orators. He was leader of a patriotic party opposing Philip of Macedon. The Third Philippic (341 BC) - The third in a series of speeches in which Demosthenes attacks Philip of Macedon. Demosthenes urged the Athenians to oppose Philip’s conquests of independent Greek states. Cicero later used the name “Philippic” to label his bitter speeches against Mark Antony; the word has since come to stand for any harsh invective. 3 THE THIRD PHILIPPIC INTRODUCTION To the Third Philippic THE former oration (The Oration on the State of the Chersonesus) has its effect: for, instead of punishing Diopithes, the Athenians supplied him with money, in order to put him in a condition of continuing his expeditions. In the mean time Philip pursued his Thracian conquests, and made himself master of several places, which, though of little importance in themselves, yet opened him a way to the cities of the Propontis, and, above all, to Byzantium, which he had always intended to annex to his dominions. He at first tried the way of negotiation, in order to gain the Byzantines into the number of his allies; but this proving ineffectual, he resolved to proceed in another manner. He had a party in the city at whose head was the orator Python, that engaged to deliver him up one of the gates: but while he was on his march towards the city the conspiracy was discovered, which immediately determined him to take another route. -

Eunuchs in the East, Men in the West? 147

Eunuchs in the East, Men in the West? 147 Chapter 8 Eunuchs in the East, Men in the West? Dis/unity, Gender and Orientalism in the Fourth Century Shaun Tougher Introduction In the narrative of relations between East and West in the Roman Empire in the fourth century AD, the tensions between the eastern and western imperial courts at the end of the century loom large. The decision of Theodosius I to “split” the empire between his young sons Arcadius and Honorius (the teenage Arcadius in the east and the ten-year-old Honorius in the west) ushered in a period of intense hostility and competition between the courts, famously fo- cused on the figure of Stilicho.1 Stilicho, half-Vandal general and son-in-law of Theodosius I (Stilicho was married to Serena, Theodosius’ niece and adopted daughter), had been left as guardian of Honorius, but claimed guardianship of Arcadius too and concomitant authority over the east. In the political manoeu- vrings which followed the death of Theodosius I in 395, Stilicho was branded a public enemy by the eastern court. In the war of words between east and west a key figure was the (probably Alexandrian) poet Claudian, who acted as a ‘pro- pagandist’ (through panegyric and invective) for the western court, or rather Stilicho. Famously, Claudian wrote invectives on leading officials at the eastern court, namely Rufinus the praetorian prefect and Eutropius, the grand cham- berlain (praepositus sacri cubiculi), who was a eunuch. It is Claudian’s two at- tacks on Eutropius that are the inspiration and central focus of this paper which will examine the significance of the figure of the eunuch for the topic of the end of unity between east and west in the Roman Empire. -

The Olynthiacs and the Phillippics of Demosthenes

The Olynthiacs and the Phillippics of Demosthenes Charles Rann Kennedy The Olynthiacs and the Phillippics of Demosthenes Table of Contents The Olynthiacs and the Phillippics of Demosthenes..............................................................................................1 Charles Rann Kennedy...................................................................................................................................1 THE FIRST OLYNTHIAC............................................................................................................................1 THE SECOND OLYNTHIAC.......................................................................................................................6 THE THIRD OLYNTHIAC........................................................................................................................10 THE FIRST PHILIPPIC..............................................................................................................................14 THE SECOND PHILIPPIC.........................................................................................................................21 THE THIRD PHILIPPIC.............................................................................................................................25 THE FOURTH PHILIPPIC.........................................................................................................................34 i The Olynthiacs and the Phillippics of Demosthenes Charles Rann Kennedy This page copyright © 2002 Blackmask Online. -

The History of Egypt Under the Ptolemies

UC-NRLF $C lb EbE THE HISTORY OF EGYPT THE PTOLEMIES. BY SAMUEL SHARPE. LONDON: EDWARD MOXON, DOVER STREET. 1838. 65 Printed by Arthur Taylor, Coleman Street. TO THE READER. The Author has given neither the arguments nor the whole of the authorities on which the sketch of the earlier history in the Introduction rests, as it would have had too much of the dryness of an antiquarian enquiry, and as he has already published them in his Early History of Egypt. In the rest of the book he has in every case pointed out in the margin the sources from which he has drawn his information. » Canonbury, 12th November, 1838. Works published by the same Author. The EARLY HISTORY of EGYPT, from the Old Testament, Herodotus, Manetho, and the Hieroglyphieal Inscriptions. EGYPTIAN INSCRIPTIONS, from the British Museum and other sources. Sixty Plates in folio. Rudiments of a VOCABULARY of EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPHICS. M451 42 ERRATA. Page 103, line 23, for Syria read Macedonia. Page 104, line 4, for Syrians read Macedonians. CONTENTS. Introduction. Abraham : shepherd kings : Joseph : kings of Thebes : era ofMenophres, exodus of the Jews, Rameses the Great, buildings, conquests, popu- lation, mines: Shishank, B.C. 970: Solomon: kings of Tanis : Bocchoris of Sais : kings of Ethiopia, B. c. 730 .- kings ofSais : Africa is sailed round, Greek mercenaries and settlers, Solon and Pythagoras : Persian conquest, B.C. 525 .- Inarus rebels : Herodotus and Hellanicus : Amyrtaus, Nectanebo : Eudoxus, Chrysippus, and Plato : Alexander the Great : oasis of Ammon, native judges, -

Seleucid Coinage and the Legend of the Horned Bucephalas

Seleucid coinage and the legend of the horned Bucephalas Autor(en): Miller, Richard P. / Walters, Kenneth R. Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Schweizerische numismatische Rundschau = Revue suisse de numismatique = Rivista svizzera di numismatica Band (Jahr): 83 (2004) PDF erstellt am: 04.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-175883 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch RICHARD P. MILLER AND KENNETH R.WALTERS SELEUCID COINAGE AND THE LEGEND OF THE HORNED BUCEPHALAS* Plate 8 [21] Balaxian est provincia quedam, gentes cuius Macometi legem observant et per se loquelam habent. Magnum quidem regnum est. Per successionem hereditariam regitur, quae progenies a rege Alexandra descendit et a filia regis Darii Magni Persarum... -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

Johnny Okane (Order #7165245) Introduction to the Hurlbat Publishing Edition

johnny okane (order #7165245) Introduction to the Hurlbat Publishing Edition Weloe to the Hurlat Pulishig editio of Miro Warfare “eries: Miro Ancients This series of games was original published by Tabletop Games in the 1970s with this title being published in 1976. Each game in the series aims to recreate the feel of tabletop wargaming with large numbers of miniatures but using printed counters and terrain so that games can be played in a small space and are very cost-effective. In these new editions we have kept the rules and most of the illustrations unchanged but have modernised the layout and counter designs to refresh the game. These basic rules can be further enhanced through the use of the expansion sets below, which each add new sets of army counters and rules to the core game: Product Subject Additional Armies Expansion I Chariot Era & Far East Assyrian; Chinese; Egyptian Expansion II Classical Era Indian; Macedonian; Persian; Selucid Expansion III Enemies of Rome Britons; Gallic; Goth Expansion IV Fall of Rome Byzantine; Hun; Late Roman; Sassanid Expansion V The Dark Ages Norman; Saxon; Viking Happy gaming! Kris & Dave Hurlbat July 2012 © Copyright 2012 Hurlbat Publishing Edited by Kris Whitmore Contents Introduction to the Hurlbat Publishing Edition ................................................................................................................................... 2 Move Procedures ............................................................................................................................................................................... -

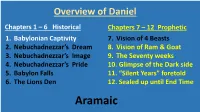

Aramaic Chapter 22 Chapter 7 Chapter 8

Overview of Daniel Chapters 1 – 6 Historical Chapters 7 – 12 Prophetic 1. Babylonian Captivity 7. Vision of 4 Beasts 2. Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream 8. Vision of Ram & Goat 3. Nebuchadnezzar’s Image 9. The Seventy weeks 4. Nebuchadnezzar’s Pride 10. Glimpse of the Dark side 5. Babylon Falls 11. “Silent Years” foretold 6. The Lions Den 12. Sealed up until End Time Aramaic Chapter 22 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Babylon Medo- Persia Greece Rome Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Persians Medes Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 8 Greek Empire Alexander The Great Lysimachus Cassander Ptolemy Seleucus Greek Empire Chapter 8 Alexander The Great King of the South King of the North 1. Ptolemy I Soter 1. Seleucus I Nicator 2. Antiochus I Soter 2. Ptolemy II Philadelphus 3. Antiochus II Theos 3. Ptolemy III Euergetes 4. Seleucus II Callinicus 5. Seleucus III Ceraunus 4. Ptolemy IV Philopator 6. Antiochus III Great 5. Ptolemy V Epiphanes 7. Seleucus IV Philopator 6. Ptolemy VI Philometor 8. Antiochus IV Epiphanes The account in 1 Maccabees continues: “Mothers who had allowed their babies to be circumcised were put to death in accordance with the king’s decree. Their babies were hung around their necks, and their families and those who had circumcised them were put to death” (1:60, TEV). ROME 10 11 8 D.T. BEAST 10 HORNS LITTLE HORN ANTI-CHRIST 3 FELL EYES & MOUTH LARGER THAN ASSOCIATES How Long? 2300 evenings & mornings = 167 BC 164 BC Antiochus Antiochus dies sacrificed a pig on the altar Start of Temple Maccabean Rededicated / Revolt cleansed He who has an ear, let him hear what the Spirit says to the churches.‘ Rev 2:7 Rev 2:11 Rev 2:17 Rev 2:29 Rev 3:6 Rev 3:13 Rev 3:22 To Gorsley in 2011 The Lord is sharpening the focus of the church and wants you to respond: with prayer and fasting and repentance and have ears to hear what the Spirit is saying and hearts and wills to respond to His leading and directing. -

A Literary Sources

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82860-4 — The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest 2nd Edition Index More Information Index A Literary sources Livy XXVI.24.7–15: 77 (a); XXIX.12.11–16: 80; XXXI.44.2–9: 11 Aeschines III.132–4: 82; XXXIII.38: 195; XXXVII.40–1: Appian, Syrian Wars 52–5, 57–8, 62–3: 203; XXXVIII.34: 87; 57 XXXIX.24.1–4: 89; XLI.20: 209 (b); ‘Aristeas to Philocrates’ I.9–11 and XLII.29–30.7: 92; XLII.51: 94; 261 V.35–40: XLV.29.3–30 and 32.1–7: 96 15 [Aristotle] Oeconomica II.2.33: I Maccabees 1.1–9: 24; 1.10–25 and 5 7 Arrian, Alexander I.17: ; II.14: ; 41–56: 217; 15.1–9: 221 8 9 III.1.5–2.2: (a); III.3–4: ; II Maccabees 3.1–3: 216 12 13 IV.10.5–12.5: ; V.28–29.1: ; Memnon, FGrH 434 F 11 §§5.7–11: 159 14 20 V1.27.3–5: ; VII.1.1–4: ; Menander, The Sicyonian lines 3–15: 104 17 18 VII.4.4–5: ; VII.8–9 and 11: Menecles of Barca FGrHist 270F9:322 26 Arrian, FGrH 156 F 1, §§1–8: (a); F 9, Pausanias I.7: 254; I.9.4: 254; I.9.5–10: 30 §§34–8: 56; I.25.3–6: 28; VII.16.7–17.1: Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae V.201b–f, 100 258 43 202f–203e: ; VI.253b–f: Plutarch, Agis 5–6.1 and 7.5–8: 69 23 Augustine, City of God 4.4: Alexander 10.6–11: 3 (a); 15: 4 (a); Demetrius of Phalerum, FGrH 228 F 39: 26.3–10: 8 (b); 68.3: cf. -

A Chronological Particular Timeline of Near East and Europe History

Introduction This compilation was begun merely to be a synthesized, occasional source for other writings, primarily for familiarization with European world development. Gradually, however, it was forced to come to grips with the elephantine amount of historical detail in certain classical sources. Recording the numbers of reported war deaths in previous history (many thousands, here and there!) initially was done with little contemplation but eventually, with the near‐exponential number of Humankind battles (not just major ones; inter‐tribal, dynastic, and inter‐regional), mind was caused to pause and ask itself, “Why?” Awed by the numbers killed in battles over recorded time, one falls subject to believing the very occupation in war was a naturally occurring ancient inclination, no longer possessed by ‘enlightened’ Humankind. In our synthesized histories, however, details are confined to generals, geography, battle strategies and formations, victories and defeats, with precious little revealed of the highly complicated and combined subjective forces that generate and fuel war. Two territories of human existence are involved: material and psychological. Material includes land, resources, and freedom to maintain a life to which one feels entitled. It fuels war by emotions arising from either deprivation or conditioned expectations. Psychological embraces Egalitarian and Egoistical arenas. Egalitarian is fueled by emotions arising from either a need to improve conditions or defend what it has. To that category also belongs the individual for whom revenge becomes an end in itself. Egoistical is fueled by emotions arising from material possessiveness and self‐aggrandizations. To that category also belongs the individual for whom worldly power is an end in itself. -

Intertestamental Period Dynasties

Intertestamental Chronologies* Year Egypt Asia Judea Texts Persian rule Persian-appointed 360 Artaxerxes II 404–358 governors Job, Jonah Artaxerxes III post-exilic 358–338 350 340 Arses 338–336 Darius III 336–331 330 Macedonian rule Alexander the Great 333–323 Greek control Wars for Succession Ptolemaic–Seleucid 320 Ptolemaic rule control (disputed) Ptolemy I Soter Zadokite High Priests 323–285 Onias I c. 320–280 310 Seleucid rule Esther Seleucus I fourth–third cent. 312–280 (Palestine) 300 Ptolemaic rule (300?) Ecclesiastes early third cent. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - (Palestine) 290 (Zadokites) 1 Enoch third to first cent. Ptolemy II 280 Philadelphus 285–246 Antiochus I Soter Simon I 280–261 c. 280–260 270 260 Antiochus II Theus Eleazar 261–246 c. 260–245 Septuagint 250 ca. 250 (Alexandria) Ptolemy III Evegetes Seleucus II Callinicus Manasseh c. 245–240 240 246–221 246–226 Onias II c. 240–218 230 Tobit late third cent. Seleucus III Ceraunus 226–223 (Palestine) 220 Ptolemy IV Philopator Antiochus III the Great 221–203 223–187 Simeon II 210 c. 218–185 200 Ptolemy V Epiphanes 203–181 Seleucid rule (200) (Simon II) Jubilees 190 third–second cent. (Palestine) Seleucus IV Philopator 187–175 Onias III Sirach 180 185–175 early second cent. Ptolemy VI (Palestine) Philometor Antiochus IV Epiphanes Jason 175–172 181–145 170 175–163 Menelaus Ptolemy VIII 172–162 169–164 Daniel Cleopatra II 160 Antiochus V 163–162 Alcimus 162–159 mid-second cent. 163–127 (Palestine) Demetrius I (unknown) 162–150 150 Hasmoneans Alexander Balas 150–145 Jonathan Apphus 152–143 Ptolemy VIII 145–131 Demetrius II Nicator 145–139 140 Cleopatra III 142–131 Antiochus VI Dionysus145–142 Simeon Tassi Diodotus Tryphon 142–139 142–134 Antiochus VII Sidetes 138–129 John Hyrcanus I 130 134–104 Demetrius II Nicator 129–126 Alexander II Zabinas 129–123 Ptolemy VIII 120 127–116 Cleopatra Thea 125–121 2 Maccabees Antiochus VIII Grypus late second cent. -

Chapter 8 Antiochus I, Antiochus IV And

Dodd, Rebecca (2009) Coinage and conflict: the manipulation of Seleucid political imagery. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/938/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Coinage and Conflict: The Manipulation of Seleucid Political Imagery Rebecca Dodd University of Glasgow Department of Classics Degree of PhD Table of Contents Abstract Introduction………………………………………………………………….………..…4 Chapter 1 Civic Autonomy and the Seleucid Kings: The Numismatic Evidence ………14 Chapter 2 Alexander’s Influence on Seleucid Portraiture ……………………………...49 Chapter 3 Warfare and Seleucid Coinage ………………………………………...…….57 Chapter 4 Coinages of the Seleucid Usurpers …………………………………...……..65 Chapter 5 Variation in Seleucid Portraiture: Politics, War, Usurpation, and Local Autonomy ………………………………………………………………………….……121 Chapter 6 Parthians, Apotheosis and political unrest: the beards of Seleucus II and Demetrius II ……………………………………………………………………….……131 Chapter 7 Antiochus III and Antiochus