Seleucid Coinage and the Legend of the Horned Bucephalas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander the Great and Hephaestion

2019-3337-AJHIS-HIS 1 Alexander the Great and Hephaestion: 2 Censorship and Bisexual Erasure in Post-Macedonian 3 Society 4 5 6 Same-sex relations were common in ancient Greece and having both male and female 7 physical relationships was a cultural norm. However, Alexander the Great is almost 8 always portrayed in modern depictions as heterosexual, and the disappearance of his 9 life-partner Hephaestion is all but complete in ancient literature. Five full primary 10 source biographies of Alexander have survived from antiquity, making it possible to 11 observe the way scholars, popular writers and filmmakers from the Victorian era 12 forward have interpreted this evidence. This research borrows an approach from 13 gender studies, using the phenomenon of bisexual erasure to contribute a new 14 understanding for missing information regarding the relationship between Alexander 15 and his life-partner Hephaestion. In Greek and Macedonian society, pederasty was the 16 norm, and boys and men did not have relations with others of the same age because 17 there was almost always a financial and power difference. Hephaestion was taller and 18 more handsome than Alexander, so it might have appeared that he held the power in 19 their relationship. The hypothesis put forward here suggests that writers have erased 20 the sexual partnership between Alexander and Hephaestion because their relationship 21 did not fit the norm of acceptable pederasty as practiced in Greek and Macedonian 22 culture or was no longer socially acceptable in the Roman contexts of the ancient 23 historians. Ancient biographers may have conducted censorship to conceal any 24 implication of femininity or submissiveness in this relationship. -

An Evaluation of Two Recent Theories Concerning the Narmer Palette1

Eras Edition 8, November 2006 – http://www.arts.monash.edu.au/eras An Evaluation of Two Recent Theories Concerning the Narmer Palette1 Benjamin P. Suelzle (Monash University) Abstract: The Narmer Palette is one of the most significant and controversial of the decorated artefacts that have been recovered from the Egyptian Protodynastic period. This article evaluates the arguments of Alan R. Schulman and Jan Assmann, when these arguments dwell on the possible historicity of the palette’s decorative features. These two arguments shall be placed in a theoretical continuum. This continuum ranges from an almost total acceptance of the historical reality of the scenes depicted upon the Narmer Palette to an almost total rejection of an historical event or events that took place at the end of the Naqada IIIC1 period (3100-3000 BCE) and which could have formed the basis for the creation of the same scenes. I have adopted this methodological approach in order to establish whether the arguments of Assmann and Schulman have any theoretical similarities that can be used to locate more accurately the palette in its appropriate historical and ideological context. Five other decorated stone artefacts from the Protodynastic period will also be examined in order to provide historical comparisons between iconography from slightly earlier periods of Egyptian history and the scenes of royal violence found upon the Narmer Palette. Introduction and Methodology Artefacts of iconographical importance rarely survive intact into the present day. The Narmer Palette offers an illuminating opportunity to understand some of the ideological themes present during the political unification of Egypt at the end of the fourth millennium BCE. -

Case 9:14-Cv-00427-MAD-TWD Document 45 Filed 06/02/16 Page 1 of 139

Case 9:14-cv-00427-MAD-TWD Document 45 Filed 06/02/16 Page 1 of 139 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK _____________________________________________ SHABAKA SHAKUR, Plaintiff, 9:14-CV-00427 v. (MAD/TWD) JUSTIN THOMAS, et al., Defendants. _____________________________________________ APPEARANCES: OF COUNSEL: SHABAKA SHAKUR Plaintiff pro se 145-38 106 Avenue Queens, NY 11435 HON. ERIC T. SCHNEIDERMAN NICOLE E. HAIMSON, ESQ. Attorney General for the State of New York Counsel for Defendants The Capitol Albany, NY 12224 THÉRÈSE WILEY DANCKS, United States Magistrate Judge ORDER AND REPORT- RECOMMENDATION This pro se prisoner civil rights action, commenced pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983, has been referred to me for Report and Recommendation by the Honorable Mae A. D’Agostino, United States District Judge, pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 636(b) and Local Rule 72.3(c). Currently before the Court for report and recommendation is Defendants’ motion to dismiss Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint (Dkt. No. 39) for failure to state a claim upon which relief may be granted, pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6). (Dkt. No. 41.) For the reasons that follow, Case 9:14-cv-00427-MAD-TWD Document 45 Filed 06/02/16 Page 2 of 139 the Court recommends that Defendants’ motion to dismiss be granted in part and denied in part. I. PROCEDURAL HISTORY On April 16, 2014, Plaintiff Shabaka Shakur commenced this civil rights action asserting claims for the violation of his rights protected under the First, Eighth, and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution and the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Person Act (“RLUIPA”), 42 U.S.C. -

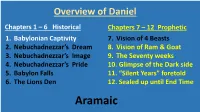

Aramaic Chapter 22 Chapter 7 Chapter 8

Overview of Daniel Chapters 1 – 6 Historical Chapters 7 – 12 Prophetic 1. Babylonian Captivity 7. Vision of 4 Beasts 2. Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream 8. Vision of Ram & Goat 3. Nebuchadnezzar’s Image 9. The Seventy weeks 4. Nebuchadnezzar’s Pride 10. Glimpse of the Dark side 5. Babylon Falls 11. “Silent Years” foretold 6. The Lions Den 12. Sealed up until End Time Aramaic Chapter 22 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Babylon Medo- Persia Greece Rome Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Persians Medes Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 8 Greek Empire Alexander The Great Lysimachus Cassander Ptolemy Seleucus Greek Empire Chapter 8 Alexander The Great King of the South King of the North 1. Ptolemy I Soter 1. Seleucus I Nicator 2. Antiochus I Soter 2. Ptolemy II Philadelphus 3. Antiochus II Theos 3. Ptolemy III Euergetes 4. Seleucus II Callinicus 5. Seleucus III Ceraunus 4. Ptolemy IV Philopator 6. Antiochus III Great 5. Ptolemy V Epiphanes 7. Seleucus IV Philopator 6. Ptolemy VI Philometor 8. Antiochus IV Epiphanes The account in 1 Maccabees continues: “Mothers who had allowed their babies to be circumcised were put to death in accordance with the king’s decree. Their babies were hung around their necks, and their families and those who had circumcised them were put to death” (1:60, TEV). ROME 10 11 8 D.T. BEAST 10 HORNS LITTLE HORN ANTI-CHRIST 3 FELL EYES & MOUTH LARGER THAN ASSOCIATES How Long? 2300 evenings & mornings = 167 BC 164 BC Antiochus Antiochus dies sacrificed a pig on the altar Start of Temple Maccabean Rededicated / Revolt cleansed He who has an ear, let him hear what the Spirit says to the churches.‘ Rev 2:7 Rev 2:11 Rev 2:17 Rev 2:29 Rev 3:6 Rev 3:13 Rev 3:22 To Gorsley in 2011 The Lord is sharpening the focus of the church and wants you to respond: with prayer and fasting and repentance and have ears to hear what the Spirit is saying and hearts and wills to respond to His leading and directing. -

A Chronological Particular Timeline of Near East and Europe History

Introduction This compilation was begun merely to be a synthesized, occasional source for other writings, primarily for familiarization with European world development. Gradually, however, it was forced to come to grips with the elephantine amount of historical detail in certain classical sources. Recording the numbers of reported war deaths in previous history (many thousands, here and there!) initially was done with little contemplation but eventually, with the near‐exponential number of Humankind battles (not just major ones; inter‐tribal, dynastic, and inter‐regional), mind was caused to pause and ask itself, “Why?” Awed by the numbers killed in battles over recorded time, one falls subject to believing the very occupation in war was a naturally occurring ancient inclination, no longer possessed by ‘enlightened’ Humankind. In our synthesized histories, however, details are confined to generals, geography, battle strategies and formations, victories and defeats, with precious little revealed of the highly complicated and combined subjective forces that generate and fuel war. Two territories of human existence are involved: material and psychological. Material includes land, resources, and freedom to maintain a life to which one feels entitled. It fuels war by emotions arising from either deprivation or conditioned expectations. Psychological embraces Egalitarian and Egoistical arenas. Egalitarian is fueled by emotions arising from either a need to improve conditions or defend what it has. To that category also belongs the individual for whom revenge becomes an end in itself. Egoistical is fueled by emotions arising from material possessiveness and self‐aggrandizations. To that category also belongs the individual for whom worldly power is an end in itself. -

Alexander's Empire

4 Alexander’s Empire MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES EMPIRE BUILDING Alexander the Alexander’s empire extended • Philip II •Alexander Great conquered Persia and Egypt across an area that today consists •Macedonia the Great and extended his empire to the of many nations and diverse • Darius III Indus River in northwest India. cultures. SETTING THE STAGE The Peloponnesian War severely weakened several Greek city-states. This caused a rapid decline in their military and economic power. In the nearby kingdom of Macedonia, King Philip II took note. Philip dreamed of taking control of Greece and then moving against Persia to seize its vast wealth. Philip also hoped to avenge the Persian invasion of Greece in 480 B.C. TAKING NOTES Philip Builds Macedonian Power Outlining Use an outline to organize main ideas The kingdom of Macedonia, located just north of Greece, about the growth of had rough terrain and a cold climate. The Macedonians were Alexander's empire. a hardy people who lived in mountain villages rather than city-states. Most Macedonian nobles thought of themselves Alexander's Empire as Greeks. The Greeks, however, looked down on the I. Philip Builds Macedonian Power Macedonians as uncivilized foreigners who had no great A. philosophers, sculptors, or writers. The Macedonians did have one very B. important resource—their shrewd and fearless kings. II. Alexander Conquers Persia Philip’s Army In 359 B.C., Philip II became king of Macedonia. Though only 23 years old, he quickly proved to be a brilliant general and a ruthless politician. Philip transformed the rugged peasants under his command into a well-trained professional army. -

The Aurea Aetas and Octavianic/Augustan Coinage

OMNI N°8 – 10/2014 Book cover: volto della statua di Augusto Togato, su consessione del Ministero dei beni e delle attivitá culturali e del turismo – Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Roma 1 www.omni.wikimoneda.com OMNI N°8 – 11/2014 OMNI n°8 Director: Cédric LOPEZ, OMNI Numismatic (France) Deputy Director: Carlos ALAJARÍN CASCALES, OMNI Numismatic (Spain) Editorial board: Jean-Albert CHEVILLON, Independent Scientist (France) Eduardo DARGENT CHAMOT, Universidad de San Martín de Porres (Peru) Georges DEPEYROT, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (France) Jean-Marc DOYEN, Laboratoire Halma-Ipel, UMR 8164, Université de Lille 3 (France) Alejandro LASCANO, Independent Scientist (Spain) Serge LE GALL, Independent Scientist (France) Claudio LOVALLO, Tuttonumismatica.com (Italy) David FRANCES VAÑÓ, Independent Scientist (Spain) Ginés GOMARIZ CEREZO, OMNI Numismatic (Spain) Michel LHERMET, Independent Scientist (France) Jean-Louis MIRMAND, Independent Scientist (France) Pere Pau RIPOLLÈS, Universidad de Valencia (Spain) Ramón RODRÍGUEZ PEREZ, Independent Scientist (Spain) Pablo Rueda RODRÍGUEZ-VILa, Independent Scientist (Spain) Scientific Committee: Luis AMELA VALVERDE, Universidad de Barcelona (Spain) Almudena ARIZA ARMADA, New York University (USA/Madrid Center) Ermanno A. ARSLAN, Università Popolare di Milano (Italy) Gilles BRANSBOURG, Universidad de New-York (USA) Pedro CANO, Universidad de Sevilla (Spain) Alberto CANTO GARCÍA, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (Spain) Francisco CEBREIRO ARES, Universidade de Santiago -

Download PDF Datastream

City of Praise: The Politics of Encomium in Classical Athens By Mitchell H. Parks B.A., Grinnell College, 2008 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2014 © Copyright 2014 by Mitchell H. Parks This dissertation by Mitchell H. Parks is accepted in its present form by the Department of Classics as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Adele Scafuro, Adviser Recommended to the Graduate Council Date Johanna Hanink, Reader Date Joseph D. Reed, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae Mitchell H. Parks was born on February 16, 1987, in Kearney, NE, and spent his childhood and adolescence in Selma, CA, Glenside, PA, and Kearney, MO (sic). In 2004 he began studying at Grinnell College in Grinnell, IA, and in 2007 he spent a semester in Greece through the College Year in Athens program. He received his B.A. in Classics with honors in 2008, at which time he was also inducted into Phi Beta Kappa and was awarded the Grinnell Classics Department’s Seneca Prize. During his graduate work at Brown University in Providence, RI, he delivered papers at the annual meetings of the Classical Association of the Middle West and South (2012) and the American Philological Association (2014), and in the summer of 2011 he taught ancient Greek for the Hellenic Education & Research Center program in Thouria, Greece, in addition to attending the British School at Athens epigraphy course. -

NW-49 Final FSR Jhelum Report

FEASIBILITY REPORT ON DETAILED HYDROGRAPHIC SURVEY IN JHELUM RIVER (110.27 KM) FROM WULAR LAKE TO DANGPORA VILLAGE (REGION-I, NW- 49) Submitted To INLAND WATERWAYS AUTHORITY OF INDIA A-13, Sector-1, NOIDA DIST-Gautam Buddha Nagar UTTAR PRADESH PIN- 201 301(UP) Email: [email protected] Web: www.iwai.nic.in Submitted By TOJO VIKAS INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD Plot No.4, 1st Floor, Mehrauli Road New Delhi-110074, Tel: +91-11-46739200/217 Fax: +91-11-26852633 Email: [email protected] Web: www.tojovikas.com VOLUME – I MAIN REPORT First Survey: 9 Jan to 5 May 2017 Revised Survey: 2 Dec 2017 to 25 Dec 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Tojo Vikas International Pvt. Ltd. (TVIPL) express their gratitude to Mrs. Nutan Guha Biswas, IAS, Chairperson, for sparing their valuable time and guidance for completing this Project of "Detailed Hydrographic Survey in Ravi River." We would also like to thanks Shri Pravir Pandey, Vice-Chairman (IA&AS), Shri Alok Ranjan, Member (Finance) and Shri S.K.Gangwar, Member (Technical). TVIPL would also like to thank Irrigation & Flood control Department of Srinagar for providing the data utilised in this report. TVIPL wishes to express their gratitude to Shri S.V.K. Reddy Chief Engineer-I, Cdr. P.K. Srivastava, Ex-Hydrographic Chief, IWAI for his guidance and inspiration for this project. We would also like to thank Shri Rajiv Singhal, A.H.S. for invaluable support and suggestions provided throughout the survey period. TVIPL is pleased to place on record their sincere thanks to other staff and officers of IWAI for their excellent support and co-operation through out the survey period. -

Rare Sarcophagus, Egyptian Scarab Found in Israel 9 April 2014, by Daniel Estrin

Rare sarcophagus, Egyptian scarab found in Israel 9 April 2014, by Daniel Estrin Van den Brink said archaeologists dug at Tel Shadud, an archaeological mound in the Jezreel Valley, from December until last month. The archaeologists first uncovered the foot of the sarcophagus and took about three weeks to work their way up the coffin. Only on one of the excavation's last days did they brush away the dirt to uncover the carved face. The lid of the clay sarcophagus is shattered, but the sculpted face remains nearly intact. It features graceful eyebrows, almond-shaped eyes, a long nose and plump lips. Ears are separated from the face, and long-fingered hands are depicted as if the dead man's arms were crossed atop his chest, in a typical Egyptian burial pose. This undated photo released by Israel's Antiquities Authority shows a sarcophagus found at Tel Shadud, an archaeological mound in the Jezreel Valley. Israeli archaeologists have unearthed a rare sarcophagus featuring a slender face and a scarab ring inscribed with the name of an Egyptian pharaoh, Israel's Antiquities Authority said Wednesday April 9, 2014. (AP Photo/ Israel's Antiquities Authority) Israeli archaeologists have unearthed a rare sarcophagus featuring a slender face and a scarab ring inscribed with the name of an Egyptian pharaoh, Israel's Antiquities Authority said Wednesday. The mystery man whose skeleton was found inside the sarcophagus was most likely a local Canaanite official in the service of ancient Egypt, Israeli archaeologists believe, shining a light on a period when pharaohs governed the region. -

Antiochus IV Rome

Chapter 22 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 11 & 12 Babylon Medo- 445BC 4 Persian Kings Persia Alex the Great Greece N&S Kings Antiochus IV Rome Gap of Time Time of the Gentiles 1wk 3 ½ years Opposing king. Greek Empire Chapter 8 Alexander The Great King of the South King of the North 1. Ptolemy I Soter 1. Seleucus I Nicator 2. Antiochus I Soter 2. Ptolemy II Philadelphus 3. Antiochus II Theos 3. Ptolemy III Euergetes 4. Seleucus II Callinicus 5. Seleucus III Ceraunus 4. Ptolemy IV Philopator 6. Antiochus III Great 5. Ptolemy V Epiphanes 7. Seleucus IV Philopator 6. Ptolemy VI Philometor 8. Antiochus IV Epiphanes Daniel 9:27 The 70th Week 1 Week = 7 years 3 ½ years 3 ½ years Apostasy Make a covenant Stop to Temple sacrifice with the many Stop to grain offering Abomination of Desolation Crush the elect (Jews) Jacob’s Distress Jacob’s Trouble Tribulation Daniel 11:35 Some of those who have insight will fall, in order to refine, purge and make them pure until the end time; because it is still to come at the appointed time 1 John 3:2-3 2 Beloved, now we are children of God, and it has not appeared as yet what we will be. We know that when He appears, we will be like Him, because we will see Him just as He is. 3 And everyone who has his hope fixed on Him purifies himself, just as He is pure. Zechariah 13:7-9 8 “It will come about in all the land,” Declares the LORD, “That two parts in it will be cut off and perish; But the third will be left in it. -

An Examination of the Political Philosophy of Plutarch's Alexander

“If I were not Alexander…” An Examination of the Political Philosophy of Plutarch’s Alexander- Caesar Richard Buckley-Gorman A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Classics 2016 School of Art History, Classics and Religious Studies 1 | P a g e Table of Contents Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………………………3 Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 Chapter One: Plutarch’s Methodology…………………………………………………………….8 Chapter Two: The Alexander………………………………………………………………………….18 Chapter Three: Alexander and Caesar……………………………………………………………47 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………………….71 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………………………….73 2 | P a g e Acknowledgements Firstly and foremost to my supervisor Jeff Tatum, for his guidance and patience. Secondly to my office mates James, Julia, Laura, Nikki, and Tim who helped me when I needed it and made research and writing more fun and less productive than it would otherwise have been. I would also like to thank my parents, Sue and Phil, for their continuous support. 3 | P a g e Abstract This thesis examines Plutarch’s Alexander-Caesar. Plutarch’s depiction of Alexander has been long recognised as encompassing many defects, including an overactive thumos and a decline in character as the narrative progresses. In this thesis I examine the way in which Plutarch depicts Alexander’s degeneration, and argue that the defects of Alexander form a discussion on the ethics of kingship. I then examine the implications of pairing the Alexander with the Caesar; I examine how some of the themes of the Alexander are reflected in the Caesar. I argue that the status of Caesar as both a figure from the Republican past and the man who established the Empire gave the pair a unique immediacy to Plutarch’s time.