Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Money, History and Energy Accounting Essay Author: Skip Sievert June 2008 Open Source Information

Some Historic aspects of money... Money, History and Energy accounting Essay author: Skip Sievert June 2008 open source information. The Technocracy Technate design uses Energy accounting as the viable alternative to the current Price System. Energy Accounting- Fezer. The Emergence of money The use of barter like methods may date back to at least 100,000 years ago. To organize production and to distribute goods and services among their populations, pre- market economies relied on tradition, top-down command, or community cooperation. Relations of reciprocity and/or redistribution substituted for market exchange. Trading in red ochre is attested in Swaziland. Shell jewellery in the form of strung beads also dates back to this period and had the basic attributes needed of commodity money. In cultures where metal working was unknown... shell or ivory jewellery was the most divisible, easily stored and transportable, relatively scarce, and impossible to counterfeit type of object that could be made into a coveted stylized ornament or trading object. It is highly unlikely that there were formal markets in 100,000 B.P. Nevertheless... something akin to our currently used concept of money was useful in frequent transactions of hunter-gatherer cultures, possibly for such things as bride purchase, prostitution, splitting possessions upon death, tribute, obtaining otherwise scarce objects or material, inter-tribal trade in hunting ground rights.. and acquiring handcrafted implements. All of these transactions suffer from some basic problems of barter — they require an improbable coincidence of wants or events. History of the beginnings of our current system Sumerian shell money below. Sumer was a collection of city states around the Lower Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what is now southern Iraq. -

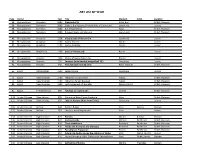

Art List by Year

ART LIST BY YEAR Page Period Year Title Medium Artist Location 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Standard of Ur Inlaid Box British Museum 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Stele of the Vultures (Victory Stele of Eannatum) Limestone Louvre 38 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Bull Headed Harp Harp British Museum 39 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Banquet Scene cylinder seal Lapis Lazoli British Museum 40 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2254 Victory Stele of Narum-Sin Sandstone Louvre 42 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Seated Diorite Louvre 43 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Standing Calcite Louvre 44 Mesopotamia Babylonian 1780 Stele of Hammurabi Basalt Louvre 45 Mesopotamia Assyrian 1350 Statue of Queen Napir-Asu Bronze Louvre 46 Mesopotamia Assyrian 750 Lamassu (man headed winged bull 13') Limestone Louvre 48 Mesopotamia Assyrian 640 Ashurbanipal hunting lions Relief Gypsum British Museum 65 Egypt Old Kingdom 2500 Seated Scribe Limestone Louvre 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun hunting fowl Fresco British Museum 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun funery banquet Fresco British Museum 80 Egypt New Kingdom 1300 Last Judgement of Hunefer Papyrus Scroll British Museum 81 Egypt First Millenium 680 Taharqo as a sphinx (2') Granite British Museum 110 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Corinthian Black Figure Amphora Vase British Museum 111 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Lady of Auxerre (Kore from Crete) Limestone Louvre 121 Ancient Greece Archaic 540 Achilles & Ajax Vase Execias Vatican 122 Ancient Greece Archaic 510 Herakles wrestling Antaios Vase Louvre 133 Ancient Greece High -

After the Battle Is Over: the Stele of the Vultures and the Beginning Of

To raise the ofthe natureof narrative is to invite After the Battle Is Over: The Stele question reflectionon the verynature of culture. Hayden White, "The Value of Narrativity . ," 1981 of the Vultures and the Beginning of Historical Narrative in the Art Definitions of narrative, generallyfalling within the purviewof literarycriticism, are nonethelessimportant to of the Ancient Near East arthistorians. From the simpleststarting point, "for writing to be narrative,no moreand no less thana tellerand a tale are required.'1 Narrativeis, in otherwords, a solutionto " 2 the problemof "how to translateknowing into telling. In general,narrative may be said to make use ofthird-person cases and of past tenses, such that the teller of the story standssomehow outside and separatefrom the action.3But IRENE J. WINTER what is importantis thatnarrative cannot be equated with thestory alone; it is content(story) structured by the telling, University of Pennsylvania forthe organization of the story is whatturns it into narrative.4 Such a definitionwould seem to providefertile ground forart-historical inquiry; for what, after all, is a paintingor relief,if not contentordered by the telling(composition)? Yet, not all figuraiworks "tell" a story.Sometimes they "refer"to a story;and sometimesthey embody an abstract concept withoutthe necessaryaction and settingof a tale at all. For an investigationof visual representation, it seems importantto distinguishbetween instancesin which the narrativeis vested in a verbal text- the images servingas but illustrationsof the text,not necessarily"narrative" in themselves,but ratherreferences to the narrative- and instancesin whichthe narrativeis located in the represen- tations,the storyreadable throughthe images. In the specificcase of the ancientNear East, instances in whichnarrative is carriedthrough the imageryitself are rare,reflecting a situationfundamentally different from that foundsubsequently in the West, and oftenfrom that found in the furtherEast as well. -

DESENVOLVIMENTO DO ESQUEMA DECORATIVO DAS SALAS DO TRONO DO PERÍODO NEO-ASSÍRIO (934-609 A.C.): IMAGEM TEXTO E ESPAÇO COMO VE

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO MUSEU DE ARQUEOLOGIA E ETNOLOGIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ARQUEOLOGIA DESENVOLVIMENTO DO ESQUEMA DECORATIVO DAS SALAS DO TRONO DO PERÍODO NEO-ASSÍRIO (934-609 a.C.): IMAGEM TEXTO E ESPAÇO COMO VEÍCULOS DA RETÓRICA REAL VOLUME I PHILIPPE RACY TAKLA Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arqueologia do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia da Universidade de São Paulo para obtenção do título de Mestre em Arqueologia. Orientadora: Profª. Drª. ELAINE FARIAS VELOSO HIRATA Linha de Pesquisa: REPRESENTAÇÕES SIMBÓLICAS EM ARQUEOLOGIA São Paulo 2008 RESUMO Este trabalho busca a elaboração de um quadro interpretativo que possibilite analisar o desenvolvimento do esquema decorativo presente nas salas do trono dos palácios construídos pelos reis assírios durante o período que veio a ser conhecido como neo- assírio (934 – 609 a.C.). Entendemos como esquema decorativo a presença de imagens e textos inseridos em um contexto arquitetural. Temos por objetivo demonstrar que a evolução do esquema decorativo, dada sua importância como veículo da retórica real, reflete a transformação da política e da ideologia imperial, bem como das fronteiras do império, ao longo do período neo-assírio. Palavras-chave: Assíria, Palácio, Iconografia, Arqueologia, Ideologia. 2 ABSTRACT The aim of this work is the elaboration of a interpretative framework that allow us to analyze the development of the decorative scheme of the throne rooms located at the palaces built by the Assyrians kings during the period that become known as Neo- Assyrian (934 – 609 BC). We consider decorative scheme as being the presence of texts and images in an architectural setting. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49596-7 — the Amorites and the Bronze Age Near East Aaron A

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49596-7 — The Amorites and the Bronze Age Near East Aaron A. Burke Index More Information INDEX ꜤꜢmw (Egyptian term), 145–47 See also Asiatics “communities of practice,” 18–20, 38–40, 42, (Egypt) 347–48 decline of, 350–51 A’ali, 226 during Early Bronze Age, 31 ‘Aa-zeh-Re’ Nehesy, 316–17 Ebla, 38–40, 56, 178 Abarsal, 45 emergence of, 23, 346–47 Abda-El (Amorite), 153–54 extensification of, 18–20 Abi-eshuh, 297, 334–35 hollow cities, 178–79 Abisare (Larsa), 160 Jazira, 38, 177 Abishemu I (Byblos), 175 “land rush,” 177–78 Abraham, 6 Mari, 38–40, 56, 177–79, 227–28 abu as symbolic kinship, 268–70 Nawar, 38, 40, 42 Abu en-Ni’aj, Tell, 65 Northern Levant, 177 Abu Hamad, 54 Qatna, 179 Abu Salabikh, 100 revival of, 176–80, 357 Abusch, Tzvi, 186 Shubat Enlil, 177–78, 180 Abydos, 220 social identity of Amorites and, 10 Achaemenid Empire, 12 Urkesh, 38, 42 Achsaph, 176 wool trade and, 23 ‘Adabal (deity), 40 Yamḫ ad, 179 Adad/Hadad (deity), 58–59, 134, 209–10, 228–29, zone of uncertainty and, 24, 174 264, 309–11, 338, 364 Ahbabu, 131 Adams, Robert, 128 Ahbutum (tribe), 97 Adamsah, 109 Ahktoy III, 147 Adba-El (Mari), 153–54 Ahmar, Tell, 51–53, 56, 136, 228 Addahushu (Elam), 320 Ahmose, 341–42 Ader, 50 ‘Ai, 33 Admonitions of Ipuwer, 172 ‘Ain Zurekiyeh, 237–38 aDNA. See DNA Ajjul, Tell el-, 142, 237–38, 326, 329, 341–42 Adnigkudu (deity), 254–55 Akkadian Empire. -

The Quest for Order O Mesopotamia: “The Land Between the Rivers”

A wall relief from an Assyrian palace of the eighth century B.C.E. depicts Gilgamesh as a heroic figure holding a lion. Page 25 • The Quest for Order o Mesopotamia: “The Land between the Rivers” o The Course of Empire o The Later Mesopotamian Empires • The Formation of a Complex Society and Sophisticated Cultural Traditions o Economic Specialization and Trade o The Emergence of a Stratified Patriarchal Society o The Development of Written Cultural Traditions • The Broader Influence of Mesopotamian Society o Hebrews, Israelites, and Jews o The Phoenicians • The Indo-European Migrations o Indo-European Origins o Indo-European Expansion and Its Effects o EYEWITNESS: Gilgamesh: The Man and the Myth B y far the best-known individual of ancient Mesopotamian society was a man named Gilgamesh. According to historical sources, Gilgamesh was the fifth king of the city of Uruk. He ruled about 2750 B.C.E.—for a period of 126 years, according to one semilegendary source—and he led his community in its conflicts with Kish, a nearby city that was the principal rival of Uruk. Historical sources record little additional detail about Gilgamesh's life and deeds. But Gilgamesh was a figure of Mesopotamian mythology and folklore as well as history. He was the subject of numerous poems and legends, and Mesopotamian bards made him the central figure in a cycle of stories known collectively as theEpic of Gilgamesh. As a figure of legend, Gilgamesh became the greatest hero figure of ancient Mesopotamia. According to the stories, the gods granted Gilgamesh a perfect body and endowed him with superhuman strength and courage. -

The Lagash-Umma Border Conflict 9

CHAPTER I Introduction: Early Civilization and Political Organization in Babylonia' The earliest large urban agglomoration in Mesopotamia was the city known as Uruk in later texts. There, around 3000 B.C., certain distinctive features of historic Mesopotamian civilization emerged: the cylinder seal, a system of writing that soon became cuneiform, a repertoire of religious symbolism, and various artistic and architectural motifs and conven- tions.' Another feature of Mesopotamian civilization in the early historic periods, the con- stellation of more or less independent city-states resistant to the establishment of a strong central political force, was probably characteristic of this proto-historic period as well. Uruk, by virtue of its size, must have played a dominant role in southern Babylonia, and the city of Kish probably played a similar role in the north. From the period that archaeologists call Early Dynastic I1 (ED 11), beginning about 2700 B.c.,~the appearance of walls around Babylonian cities suggests that inter-city warfare had become institutionalized. The earliest royal inscriptions, which date to this period, belong to kings of Kish, a northern Babylonian city, but were found in the Diyala region, at Nippur, at Adab and at Girsu. Those at Adab and Girsu are from the later part of ED I1 and are in the name of Mesalim, king of Kish, accompanied by the names of the respective local ruler^.^ The king of Kish thus exercised hegemony far beyond the walls of his own city, and the memory of this particular king survived in native historical traditions for centuries: the Lagash-Umma border was represented in the inscriptions from Lagash as having been determined by the god Enlil, but actually drawn by Mesalim, king of Kish (IV.1). -

Chapter 2 the Rise of Civilization: the Art of the Ancient Near East

Chapter 2 The Rise of Civilization: The Art of the Ancient Near East Multiple Choice Select the response that best answers the question or completes the statement. 1. The change in the nature of daily life, from hunter and gatherer to farmer and herder, first occurred in ______________. a. Mesopotamia c. Africa b. Europe d. Asia 2. Mesopotamia is known as the __________ ___________. a. River Crescent c. Fertile Crescent b. Delta Crescent d. Pearl Crescent 3. The ___________ ruled the northern Mesopotamian empire during the ninth through seventh centuries BCE. a. Sumerians c. Akkadians b. Assyrians d. Sasanians 4. What site did Leonard Woolley excavate in the 1920s in southern Mesopotamia? a. Royal Cemetery at Giza c. Royal Palace at Nineveh b. Ziggurat of Ur d. Royal Cemetery at Ur 5. The ___________ are credited with developing the first known writing system. a. Assyrians c. Sumerians b. Babylonians d. Elamites 6. The most famous Sumerian work of literature is the _____________________. a. Illiad c. Odyssey b. Tale of Gilgamesh d. Tale of Urnanshe 7. In Sumerian cities the ________ formed the nucleus of the city. a. temple c. palace b. market d. treasury 8. The temples of Sumer were placed on high platforms or ___________. a. pyramids c. daises b. ziggurats d. towers 9. What is the theme of the Stele of the Vultures? a. warfare c. trade b. prayer d. royal contract 7 10. The earliest known name of an author is _____________. a. Nanna c. Sargon b. Enheduanna d. Gudea 11. Hammurabi is most famous for his ____________. -

Ancient Near East Art

ANCIENT NEAR EAST ART ANCIENT NEAR EAST ANCIENT NEAR EAST IRAQ ANCIENT NEAR EAST “Some Apples, Bananas And Peaches…” -- Mr. Curless ANCIENT NEAR EAST City of UR (first independent city-state) – Anu and Nanna Ziggurats – developed 1st writing system – VOTIVE SUMERIAN FIGURES – Cylinder seals for stamping – EPIC OF GILGAMESH – invention of the wheel Sargon I defeats Sumerians – Stele of Naramsin – AKKADIAN heiratic scale – brutality in art Neo-Sumerian – Gudea of Lagash United Sumer under Hammurabi (1792 – 1750 BCE) BABYLONIAN – Stele of Hammurabi with his Code of Laws – Creation Myths Took control around 1400 BCE – King Assurbanipal – kept library, ziggurat form & Sumerian texts – Human-head lion LAMASSUs ASSYRIAN guard palace Neo-Babylonian – Nebuchadnezzar II PERSIAN Cyrus & the citadel at Persepolis (built between 521-465 BCE) ANCIENT NEAR EAST Sumerian Art White Temple and its ziggurat at Ur. Uruk (now Warka, Iraq), 3500-3000 BCE. Sun-dried and fired mudbrick. SUMERIAN The temple is named after its whitewashed walls and it stands atop a ziggurat, a high platform. Sumerian builders did not have access to stone quarries and instead formed mud bricks for the superstructures of their temples and other buildings. Almost all these structures have eroded over the course of time. The fragile nature of the building materials did not, however, prevent the Sumerians from erecting towering works, such as the Uruk temple, several centuries before the Egyptians built their stone pyramids. Enough of the Uruk complex remains to permit a fairly reliable reconstruction drawing. The temple (most likely dedicated to the sky god Anu) stands on top of a high platform, or ziggurat, 40 feet above street level in the city center. -

An AZ Companion to Ancient Egyptian Architecture Free

FREE THE MONUMENTS OF EGYPT: AN A-Z COMPANION TO ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE PDF Dieter Arnold | 288 pages | 30 Nov 2009 | I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd | 9781848850422 | English | London, United Kingdom Art of ancient Egypt - Wikipedia Egyptian inventions and discoveries are objects, processes or techniques which owe their existence either partially or entirely to an Egyptian person. Often, things which are discovered for the first time, are also called "inventions", and in many cases, there is no clear line between the two. Below is a list of such inventions. Furniture became common first in Ancient Egypt during the Naqada culture. During that period a wide variety of furniture pieces were invented and used. Atalla and Dawon Kahng at Bell Labs in[] enabled the practical use of metal—oxide—semiconductor MOS transistors as memory cell storage elements, a function previously served by magnetic cores. MOSFET scaling and miniaturization see List of semiconductor scale examples have been the primary factors behind the rapid exponential growth of electronic semiconductor technology since the s, [] as the rapid miniaturization of MOSFETs has been largely responsible for the increasing The Monuments of Egypt: An A-Z Companion to Ancient Egyptian Architecture densityincreasing performance and decreasing power consumption of integrated circuit chips and electronic devices since the s. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Redirected from List of egyptian inventions and discoveries. This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. June Archived from the original on Archived from the original PDF on January A history of ancient Egypt. Shaw, Ian, —. Oxford, UK: — Mark 4 November Ancient History Encyclopedia. -

Hittite Rock Reliefs in Southeastern Anatolia As a Religious Manifestation of the Late Bronze and Iron Ages

HITTITE ROCK RELIEFS IN SOUTHEASTERN ANATOLIA AS A RELIGIOUS MANIFESTATION OF THE LATE BRONZE AND IRON AGES A Master’s Thesis by HANDE KÖPÜRLÜOĞLU Department of Archaeology İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University Ankara September 2016 HITTITE ROCK RELIEFS IN SOUTHEASTERN ANATOLIA AS A RELIGIOUS MANIFESTATION OF THE LATE BRONZE AND IRON AGES The Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University by Hande KÖPÜRLÜOĞLU In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY September 2016 ABSTRACT HITTITE ROCK RELIEFS IN SOUTHEASTERN ANATOLIA AS A RELIGIOUS MANIFASTATION OF THE LATE BRONZE AND IRON AGES Köpürlüoğlu, Hande M.A., Department of Archaeology Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Marie-Henriette Gates September 2016 The LBA rock reliefs are the works of the last three or four generations of the Hittite Empire. The first appearance of the Hittite rock relief is dated to the reign of Muwatalli II who not only sets up an image on a living rock but also shows his own image on his seals with his tutelary deity, the Storm-god. The ex-urban settings of the LBA rock reliefs and the sacred nature of the religion make the work on this subject harder because it also requires philosophical and theological evaluations. The purpose of this thesis is to evaluate the reasons for executing rock reliefs, understanding the depicted scenes, revealing the subject of the depicted figures, and to interpret the purposes of the rock reliefs in LBA and IA. Furthermore, the meaning behind the visualized religious statements will be investigated. -

A HISTORY of the WORLD in 100 OBJECTS Neil Macgregor

A HISTORY OF THE WORLD IN 100 OBJECTS Neil MacGregor THE EBB RADI a BRITISH ° MUSEUM 92-95 FM ALLEN LANE an imprint of PENGUIN BOOKS Contents Preface: Mission Impossible xiii Introduction: Signals from the Past xv PART ONE Making us Human 2,000,000-9000 BC 1. Mummy of Hornedj itef 2 2. Olduvai Stone Chopping Tool 9 3. Olduvai Handaxe 15 4. Swimming Reindeer 19 5. Clovis Spear Point 26 PART TWO After the Ice Age: Food and Sex 9000-3500 BC 6. Bird-shaped Pestle 32 7. Ain Sakhri Lovers Figurine 37 8. Egyptian Clay Model of Cattle 43 9. Maya Maize God Statue 49 10. JomonPot 55 PART THREE The First Cities and States 4OOO-2OOO BC 11. King Den's Sandal Label 62 12. Standard of Ur 68 i). Indus Seal 78 14. Jade Axe 84 ij\ Early Writing Tablet 90 Vll CONTENTS PART FOUR The Beginnings of Science and Literature 2000-700 BC 16. Flood Tablet 96 iy. Rhind Mathematical Papyrus 102 18. Minoan Bull-leaper 111 19. Mold Gold Cape 117 20. Statue of Ramesses II 124 PART FIVE Old World, New Powers IIOO-3OO BC 21. Lachish Reliefs 132 22. Sphinx of Taharqo 140 23. Chinese Zhou Ritual Vessel 146 24. ParacasTextile 153 25. Gold Coin of Croesus 158 PART six The World in the Age of Confucius 500-300 BC 2.6. Oxus Chariot Model 164 27. Parthenon Sculpture: Centaur and Lapith 171 28. Basse-Yutz Flagons 177 29. Olmec Stone Mask 183 30. Chinese Bronze Bell 190 PART SEVEN Empire Builders 300 BC-AD 10 31.