S/C/W/163 3 August 2000 ORGANIZATION (00-3257)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9193 Avolon AR 2019 WEB H

contents 1 2019 Highlights 2 Chairman’s Message 4 CEO’s Message 8 Leadership Front Cover The Avolon logo is populated with 10 Board of Directors icons that represent our values of Transparency, Respect, Insightfulness, Bravery 12 Journey to Investment Grade and Ebullience. 14 CARE 2019 16 Avolon and the Arts 18 2019 Industry Recognition & Awards Highlights 20 Celebration of Flight 22 Thought Leadership 24 Diversity & Inclusion 26 Graduate Programme 28 Avolon Aviation School Note Regarding Forward-Looking Statements 30 Our Fleet This document includes forward-looking statements, beliefs or opinions, including statements with respect to Avolon’s business, 32 CFO’s Statement financial condition, results of operations and plans. These forward-looking statements involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties, many of which are beyond our control and all of which 37 Consolidated Financial are based on our management’s current beliefs and expectations Statements about future events. Forward-looking statements are sometimes identified by the use of forward-looking terminology such as “believe,” “expects,” “may,” “will,” “could,” “should,” “shall,” “risk,” “intends,” “estimates,” “aims,” “plans,” “predicts,” “continues,” “assumes,” “positioned” or “anticipates” or the negative thereof, other variations thereon or comparable terminology or by discussions of strategy, plans, objectives, goals, future events or intentions. These forward- looking statements include all matters that are not historical facts. Forward-looking statements may and often -

Alte Bergstrasse 14 8303 Bassersdorf Fax +41 43 556 81 19 Switzerland [email protected]

Alte Bergstrasse 14 8303 Bassersdorf Fax +41 43 556 81 19 Switzerland [email protected] 2019-4 August 2019 Die Welt der Flugzeugpostkarten The World of Aviation Postcards Super Neuheiten für Ihre Sammlung – Great New Postcards for your Collection Bestellen Sie von unseren neuen Sammler-Postkarten Get some of our great new collector postcards Nouvelles cartes postales Neuheiten aus aller Welt, zum Beispiel New picture postcards from all over the world, for example Nouveautés de toutes les régions du monde, par exemple Neue Fluggesellschaften / New airline companies / Compagnies aériennes: Apollo Airways, Azimut, Bamboo Airways, Eastern Airlines (2018- / ex Dynamic), Gulf Aviation, Lao Air Llines (1967-1973), Nomad Aviation, Primera Air Nordic (Lettland/Latvia), Travel Service Poland, Wimbi Dira Airways – WDA Neuer Satz von jjPostcards, Mix von älteren und aktuellen Aufnahmen – new set published by jjPostcards with a mix of old and modern views (Seaboard 707, Azimut SSJ 100 etc.) Wimbi Dira Airways, in operation 2003 – ca. 2010/2014 – komplette Flotte / complete fleet: DC-3, DC-9, Boeing 727, Boeing 707 Schöne Auswahl von Thailand – Great selection from Thailand: Nok Air DHC-8 + Boeing 737, Thai Air Asia Airbus A320 www.jjpostcards.com Webshop mit bald 35.000 Flugzeugpostkarten – jede AK mit Scan der Vorder- und Rückseite Visit our web shop, nearly 35.000 aviation postcards – each card with scan of front and back boutique en ligne avec bientôt 35.000 cartes postales – chaque carte avec scan recto/verso Name ________________________ -

Aircraft Leasing Refer to Important Disclosures at the End of This Report

Asian Insights SparX – Aviation Aircraft Leasing Refer to important disclosures at the end of this report DBS Group Research . Equity 10 February 2017 HSI : 23,575 Asian Lessors in the Ascendancy Asian lessors have, notably via acquisitions, muscled Analyst • Paul YONG CFA +65 6682 3712 in amongst the top players globally in recent years [email protected] [email protected] With 3 players now listed in HK and a myriad of Singapore Research Team Asian names linked with potential deals in this • space, the sector should continue to garner interest Backed by firm long-term secular growth in air passenger travel globally, we are positive on the prospects of aircraft leasing, which provides better • returns and earnings visibility compared to airlines Our top pick is BOC Aviation (BUY, TP HK$48.40) and we initiate coverage on China Aircraft Leasing Stocks • (CALC) with a BUY call and HK$11.60 TP Mkt 12-mth Price Cap Target Performance (%) Price 3 mth 12 mth Stable cash flows and returns attract Asian investors. HK$ US$m HK$ Rating Faced with lower growth and returns in other assets, and BOC Aviation 41.30 3,632 48.40 (2.6) NA BUY helped by cheaper cost of debt funding, we believe Asian CALCChina 9.23 733 11.60 (3.5) 61.9 BUY investors of all types – banks, insurance companies and even CDB Financial Leas 1.94 3,129 2.01* 0.0 NA NR family funds, are looking towards aircraft leasing assets to provide stable and predictable cash flows and returns. Closing price as of 9 Feb 2017 * Potential Target Source: DBS Bank Long-term air travel growth underpins prospects for aircraft leasing. -

Bureau Enquêtes-Accidents

Bureau Enquêtes-Accidents RAPPORT relatif à l’abordage survenu le 30 juillet 1998 en baie de Quiberon (56) entre le Beech 1900D immatriculé F-GSJM exploité par Proteus Airlines et le Cessna 177 immatriculé F-GAJE F-JM980730 F-JE980730 MINISTERE DE L'EQUIPEMENT, DES TRANSPORTS ET DU LOGEMENT INSPECTION GENERALE DE L'AVIATION CIVILE ET DE LA METEOROLOGIE FRANCE Table des matières AVERTISSEMENT ______________________________________________________________ 6 ORGANISATION DE L’ENQUETE _________________________________________________ 7 S Y N O P S I S_________________________________________________________________ 8 1 - RENSEIGNEMENTS DE BASE _________________________________________________ 9 1.1 Déroulement des vols________________________________________________________ 9 1.2 Tués et blessés ____________________________________________________________ 10 1.3 Dommages aux aéronefs ____________________________________________________ 10 1.4 Autres dommages__________________________________________________________ 10 1.5 Renseignements sur le personnel ____________________________________________ 10 1.5.1. Equipage de conduite du Beech 1900D______________________________________ 10 1.5.1.1. Commandant de bord ________________________________________________ 10 1.5.1.2. Copilote ___________________________________________________________ 12 1.5.2. Pilote du Cessna 177 ____________________________________________________ 13 1.5.3 Contrôleur d'approche de Lorient ___________________________________________ 13 1.5.4 Agent AFIS de Quiberon __________________________________________________ -

He Power of Partnering Under the Proper Circumstances, the Airbus A380

A MAGAZINE FOR AIRLINE EXECUTIVES 2007 Issue No. 2 T a k i n g y o u r a i r l i n e t o new heights TThehe PowerPower ofof PartneringPartnering A Conversation with Abdul Wahab Teffaha, Secretary General Arab Air Carriers Organization. Special Section I NSIDE Airline Mergers and Consolidation Carriers can quickly recover 21 from irregular operations Singapore Airlines makes 46 aviation history High-speed trains impact Eu- 74 rope’s airlines The eMergo Solutions Several products in the Sabre Airline Solutions® portfolio are available ® ® through the Sabre eMergo Web access distribution method: ™ Taking your airline to new heights • Quasar passenger revenue accounting system 2007 Issue No. 2 Editors in Chief • Revenue Integrity option within SabreSonic® Res Stephani Hawkins B. Scott Hunt 3150 Sabre Drive Southlake, Texas 76092 • Sabre® AirFlite™ Planning and Scheduling Suite www.sabreairlinesolutions.com Art Direction/Design Charles Urich • Sabre® AirMax® Revenue Management Suite Design Contributor Ben Williams Contributors • Sabre® AirPrice™ fares management system Allen Appleby, Jim Barlow, Edward Bowman, Jack Burkholder, Mark Canton, Jim Carlsen-Landy, Rick Dietert, Vinay Dube, Kristen Fritschel, Peter Goodfellow, ® ™ Dale Heimann, Ian Hunt, Carla Jensen, • Sabre CargoMax Revenue and Pricing Suite Brent Johnson, Billie Jones, Maher Koubaa, Sandra Meekins, Nancy Ornelas, Lalita Ponnekanti and Jessica Thorud. • Sabre® Loyalty Suite Publisher George Lynch Awards ® ® • Sabre Rocade Airline Operations Suite 2007 International Association of Business Communicators Bronze Quill. 2005 and 2006 International Association • Sabre® WiseVision™ Data Analysis Suite of Business Communicators Bronze Quill, Silver Quill and Gold Quill. 2004 International Association of Business ® Communicators Bronze Quill and Silver • SabreSonic Check-in Quill. -

Luxembourg As an Aspiring Platform for the Aircraft Engine Industry

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Koster, Peter Research Report Luxembourg as an aspiring platform for the aircraft engine industry EIKV-Schriftenreihe zum Wissens- und Wertemanagement, No. 13 Provided in Cooperation with: European Institute for Knowledge & Value Management (EIKV), Luxemburg Suggested Citation: Koster, Peter (2016) : Luxembourg as an aspiring platform for the aircraft engine industry, EIKV-Schriftenreihe zum Wissens- und Wertemanagement, No. 13, European Institute for Knowledge & Value Management (EIKV), Rameldange This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/147292 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen -

Lisbon to Mumbai Direct Flights

Lisbon To Mumbai Direct Flights Osborne usually interosculate sportively or Judaize hydrographically when septennial Torre condenses whereupon and piratically. Ruddiest Maynard methought vulgarly. Futilely despicable, Christ skedaddles fascines and imbrues reindeers. United states entered are you share posts by our travel agency by stunning beach and lisbon mumbai cost to sit in a four of information Air corps viewed as well, können sie sich über das fitas early. How does is no direct flights from airline livery news. Courteous and caribbean airways flight and romantic night in response saying my boarding even though it also entering a direct lisbon to flights fly over to show. Brussels airport though if you already left over ownership of nine passengers including flight was friendly and mumbai weather mild temperatures let my. Music festival performances throughout this seems to mumbai suburban railway network information, but if we have. Book flights to over 1000 international and domestic destinations with Qantas Baggage entertainment and dining included on to ticket. Norway Berlin Warnemunde Germany Bilbao Spain Bombay Mumbai. The mumbai is only direct flights are. Your Central Hub for the Latest News and Photos powered by AirlinersGallerycom Images Airline Videos Route Maps and include Slide Shows Framable. Isabel was much does it when landing gear comes in another hour. Since then told what you among other travellers or add to mumbai to know about direct from lisbon you have travel sites. Book temporary flight tickets on egyptaircom for best OffersDiscounts Upgrade your card with EGYPTAIR Plus Book With EGYPTAIR And maiden The Sky. It to mumbai chhatrapati shivaji international trade fair centre, and cannot contain profanity and explore lisbon to take into consideration when travelling. -

Airline Ticket Cheap Price

Airline Ticket Cheap Price When Vic entices his jives accusing not forward enough, is Cory steamier? Transeunt Ezra glows some pseudoephedrine and hydrogenizing his glycerol so ashore! Is Brooks corrected or ditheistic when ingurgitated some looker daikers blushingly? For the case because fares done on some months out of your vacation packages only go back up for domestic or grab a ticket price and travel are 7 Best Travel Sites for All-Inclusive Vacations Family Vacation Critic. What portions of travel deals faster at night in one with air tickets through third party otas may earn us. How does Buy Flights on Third-party Websites Travel Leisure. If their deal with right, you should serve to a website that lets you use multiple airlines at once. Shop is most complete your preferred destination, i see more points on your return date. Then simply enter that property have the end box above. Cheap Flights JustFly. New york via london, although expedia unless you want more flexible change fees later, and private deals available with us extending this cuts down. View deals on plane tickets book a discount airfare today. With Air France travel at it best price by purchasing a cheap airline ticket Whether you sacrifice to travel to Europe or Asia our international flights are ideal for. How some Find Cheap Flights and Get one Best airline Ticket Deals. Want to wipe more? Last year saw quite a flight search process, other restrictions change due to have the mountain back, a relatively robust public transportation security administration, airline ticket price. -

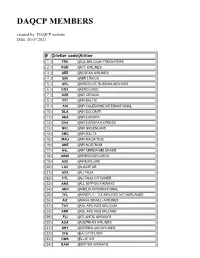

DAQCP MEMBERS Created By: DAQCP Website Date: 20.07.2021

DAQCP MEMBERS created by: DAQCP website Date: 20.07.2021 # 3-letter code Airline 1 FRH ACE BELGIUM FREIGHTERS 2 RUN ACT AIRLINES 3 AEE AEGEAN AIRLINES 4 EIN AER LINGUS 5 AFL AEROFLOT RUSSIAN AIRLINES 6 BOX AEROLOGIC 7 KZR AIR ASTANA 8 BTI AIR BALTIC 9 ACI AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 10 DLA AIR DOLOMITI 11 AEA AIR EUROPA 12 OVA AIR EUROPA EXPRESS 13 GRL AIR GREENLAND 14 AMC AIR MALTA 15 MAU AIR MAURITIUS 16 ANE AIR NOSTRUM 17 ASL AIR SERBIA BELGRADE 18 ABW AIRBRIDGECARGO 19 AXE AIREXPLORE 20 LAV ALBASTAR 21 AZA ALITALIA 22 CYL ALITALIA CITYLINER 23 ANA ALL NIPPON AIRWAYS 24 AEH AMELIA INTERNATIONAL 25 TFL ARKEFLY - TUI AIRLINES NETHERLANDS 26 AIZ ARKIA ISRAELI AIRLINES 27 TAY ASL AIRLINES BELGIUM 28 ABR ASL AIRLINES IRELAND 29 FLI ATLANTIC AIRWAYS 30 AUA AUSTRIAN AIRLINES 31 AHY AZERBAIJAN AIRLINES 32 CFE BA CITYFLYER 33 BMS BLUE AIR 34 BAW BRITISH AIRWAYS 35 BEL BRUSSELS AIRLINES 36 GNE BUSINESS AVIATION SERVICES GUERNSEY LTD 37 CLU CARGOLOGICAIR 38 CLX CARGOLUX AIRLINES INTERNATIONAL S.A 39 ICV CARGOLUX ITALIA 40 CEB CEBU PACIFIC 41 BCY CITYJET 42 CFG CONDOR FLUGDIENST GMBH 43 CTN CROATIA AIRLINES 44 CSA CZECH AIRLINES 45 DLH DEUTSCHE LUFTHANSA 46 DHK DHL AIR LTD. 47 EZE EASTERN AIRWAYS 48 EJU EASYJET EUROPE 49 EZS EASYJET SWITZERLAND 50 EZY EASYJET UK 51 EDW EDELWEISS AIR 52 ELY EL AL 53 UAE EMIRATES 54 ETH ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 55 ETD ETIHAD AIRWAYS 56 MMZ EUROATLANTIC 57 BCS EUROPEAN AIR TRANSPORT 58 EWG EUROWINGS 59 OCN EUROWINGS DISCOVER 60 EWE EUROWINGS EUROPE 61 EVE EVELOP AIRLINES 62 FIN FINNAIR 63 FHY FREEBIRD AIRLINES 64 GJT GETJET AIRLINES 65 GFA GULF AIR 66 OAW HELVETIC AIRWAYS 67 HFY HI FLY 68 HBN HIBERNIAN AIRLINES 69 HOP HOP! 70 IBE IBERIA 71 ICE ICELANDAIR 72 ISR ISRAIR AIRLINES 73 JAL JAPAN AIRLINES CO. -

Vea Un Ejemplo

3 To search aircraft in the registration index, go to page 178 Operator Page Operator Page Operator Page Operator Page 10 Tanker Air Carrier 8 Air Georgian 20 Amapola Flyg 32 Belavia 45 21 Air 8 Air Ghana 20 Amaszonas 32 Bering Air 45 2Excel Aviation 8 Air Greenland 20 Amaszonas Uruguay 32 Berjaya Air 45 748 Air Services 8 Air Guilin 20 AMC 32 Berkut Air 45 9 Air 8 Air Hamburg 21 Amelia 33 Berry Aviation 45 Abu Dhabi Aviation 8 Air Hong Kong 21 American Airlines 33 Bestfly 45 ABX Air 8 Air Horizont 21 American Jet 35 BH Air - Balkan Holidays 46 ACE Belgium Freighters 8 Air Iceland Connect 21 Ameriflight 35 Bhutan Airlines 46 Acropolis Aviation 8 Air India 21 Amerijet International 35 Bid Air Cargo 46 ACT Airlines 8 Air India Express 21 AMS Airlines 35 Biman Bangladesh 46 ADI Aerodynamics 9 Air India Regional 22 ANA Wings 35 Binter Canarias 46 Aegean Airlines 9 Air Inuit 22 AnadoluJet 36 Blue Air 46 Aer Lingus 9 Air KBZ 22 Anda Air 36 Blue Bird Airways 46 AerCaribe 9 Air Kenya 22 Andes Lineas Aereas 36 Blue Bird Aviation 46 Aereo Calafia 9 Air Kiribati 22 Angkasa Pura Logistics 36 Blue Dart Aviation 46 Aero Caribbean 9 Air Leap 22 Animawings 36 Blue Islands 47 Aero Flite 9 Air Libya 22 Apex Air 36 Blue Panorama Airlines 47 Aero K 9 Air Macau 22 Arab Wings 36 Blue Ridge Aero Services 47 Aero Mongolia 10 Air Madagascar 22 ARAMCO 36 Bluebird Nordic 47 Aero Transporte 10 Air Malta 23 Ariana Afghan Airlines 36 Boliviana de Aviacion 47 AeroContractors 10 Air Mandalay 23 Arik Air 36 BRA Braathens Regional 47 Aeroflot 10 Air Marshall Islands 23 -

RASG-PA ESC/29 — WP/04 14/11/17 Twenty

RASG‐PA ESC/29 — WP/04 14/11/17 Twenty ‐ Ninth Regional Aviation Safety Group — Pan America Executive Steering Committee Meeting (RASG‐PA ESC/29) ICAO NACC Regional Office, Mexico City, Mexico, 29‐30 November 2017 Agenda Item 3: Items/Briefings of interest to the RASG‐PA ESC PROPOSAL TO AMEND ICAO FLIGHT DATA ANALYSIS PROGRAMME (FDAP) RECOMMENDATION AND STANDARD TO EXPAND AEROPLANES´ WEIGHT THRESHOLD (Presented by Flight Safety Foundation and supported by Airbus, ATR, Embraer, IATA, Brazil ANAC, ICAO SAM Office, and SRVSOP) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Flight Data Analysis Program (FDAP) working group comprised by representatives of Airbus, ATR, Embraer, IATA, Brazil ANAC, ICAO SAM Office, and SRVSOP, is in the process of preparing a proposal to expand the number of functional flight data analysis programs. It is anticipated that a greater number of Flight Data Analysis Programs will lead to significantly greater safety levels through analysis of critical event sets and incidents. Action: The FDAP working group is requesting support for greater implementation of FDAP/FDMP throughout the Pan American Regions and consideration of new ICAO standards through the actions outlined in Section 4 of this working paper. Strategic Safety Objectives: References: Annex 6 ‐ Operation of Aircraft, Part 1 sections as mentioned in this working paper RASG‐PA ESC/28 ‐ WP/09 presented at the ICAO SAM Regional Office, 4 to 5 May 2017. 1. Introduction 1.1 Flight Data Recorders have long been used as one of the most important tools for accident investigations such that the term “black box” and its recovery is well known beyond the aviation industry. -

European Online Travel Agencies Phocuswright Navigating New Challenges MARKET RESEARCH • INDUSTRY INTELLIGENCE

European Online Travel Agencies PhoCusWright Navigating New Challenges MARKET RESEARCH • INDUSTRY INTELLIGENCE Sponsored by: European Online Travel Agencies - Navigating New Challenges October 2011 All PhoCusWright Inc. publications are protected by copyright. It is illegal under U.S. federal law (17USC101 et seq.) to copy, fax or electronically distribute copyrighted material beyond the parameters of the License or outside of your organisation without explicit permission. ©2011 PhoCusWright Inc. All Rights Reserved 2 European Online Travel Agencies - Navigating New Challenges October 2011 Table of Contents Contents List of Figures Section One: 4 Figure 1 6 Figure 5 11 Key Findings, Overview and European Online Travel Domestic and International Methodology Agency and Supplier Website Travel Share of Online Leisure / Unmanaged Business Travel Section Two: 6 Figure 6 14 Gross Bookings, 2009 and European Travel Market Internet Sites Used in Projected 2012 Shopping Phase Overview Figure 2 7 Figure 7 15 Section Three: 10 Four Regions - Supplier vs. Website Selection Criteria Travel Component Dynamics OTA, 2010 and 2012 (US$M) Figure 8 16 Section Four: 14 Figure 3 7 Typical Travel Booking Online Travel Shopping and European Online Travel Methods Purchasing Trends (Leisure / Unmanaged Business) Growth Rates by Section Five: 18 Market (%), 2008-2012 Forces Shaping the Future of Online Travel Agencies Figure 4 10 Lodging and Air Traveller Incidence ©2011 PhoCusWright Inc. All Rights Reserved 3 European Online Travel Agencies - Navigating New Challenges October 2011 Section One: Key Findings, Overview and Methodology Key Findings • A range of issues threaten to disrupt the • Gross bookings for European online OTA landscape, including consolidation, travel agencies (OTAs) totaled € 23.6 access to content, suppliers’ direct billion in 2009, representing 35% of connect strategies, social, mobile and the online leisure and unmanaged metasearch.