A Display of Acadian Perseverance and Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antonine Maillets La Sagouine : Interdisziplinäre Begegnungen in Der Akadie Georg A

Antonine Maillets La Sagouine : Interdisziplinäre Begegnungen in der Akadie Georg A. Kaiser & Florian Freitag 1 (Konstanz/Mainz) 1. Einleitung In diesem Beitrag möchten wir zeigen, dass bestimmte Texte der America Romana an Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaftler besondere Herausforde- rungen stellen und eine Herangehensweise erfordern, die die institutiona- lisierte disziplinäre Trennung zwischen Sprachwissenschaften einerseits und Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaften andererseits überwindet. Die Idee für diesen Beitrag entstand durch eine solche Überwindung dieser Trennung in der Lehre, im Rahmen zweier z.T. gemeinsam, z.T. parallel unterrichteter Seminare „Das Französische in Nordamerika“ und „Intro- duction à l’Amérique française“ im Wintersemester 2010/2011 an der Universität Konstanz. In diesen Seminaren erwiesen sich v.a. diejenigen Texte als eine be- sondere Herausforderung (für die Studierenden wie auch für die Lehren- den), die sich durch eine dezidierte Oralität auszeichnen, die also in ver- schiedenen, vom Frankreichfranzösischen teilweise stark abweichenden, dialektalen und soziolektalen Varietäten des nordamerikanischen Franzö- sisch verfasst sind. Dazu zählen z.B. sogenannte romans de la terre aus Québec wie etwa Ringuets Trente arpents (1938), in denen zwar die Erzäh- lerstimme Frankreichfranzösisch, die einzelnen Charaktere in direkter Rede jedoch Québec-Französisch verwenden. Insbesondere zählen hier- zu aber Werke des mundartlichen Theaters Frankokanadas wie etwa Mi- chel Tremblays im Montréaler Arbeiterdialekt joual verfasster Skandaler- folg Les belles-sœurs (1968) sowie das nur drei Jahre später veröffentlichte und im akadischen Französisch verfasste La Sagouine der aus New Brunswick stammenden Autorin Antonine Maillet, auf das wir uns im Folgenden konzentrieren möchten. 1 Die Autoren bedanken sich bei Stefano Quaglia, Sandra Tinner und Michael Zimmermann für hilfreiche Kommentare. Antonine Maillets La Sagouine : Interdisziplinäre Begegnungen in der Akadie 2. -

Queer(Y)Ing Quaintness: Destabilizing Atlantic Canadian Identity Through Its Theatre

QUEER(Y)ING QUAINTNESS: DESTABILIZING ATLANTIC CANADIAN IDENTITY THROUGH ITS THEATRE LUKE BROWN Thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in Theatre Theory & Dramaturgy Department of Theatre Faculty of Graduate Studies University of Ottawa © Luke Brown, Ottawa, Canada, 2019 Brown ii Abstract The Atlantic Canadian provinces (Newfoundland, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia) have long been associated with agricultural romanticism. Economically and culturally entrenched in a stereotype of quaintness (Anne of Green Gables is just one of many examples), the region continuously falls into a cycle of inferiority. In this thesis, I argue that queer theory can be infused into performance analysis to better situate local theatre practice as a site of mobilization. Using terms and concepts from queer geographers and other scholars, particularly those who address capitalism (Gibson-Graham, Massey), this research outlines a methodology of performance analysis that looks through a queer lens in order to destabilize normative assumptions about Atlantic Canada. Three contemporary performances are studied in detail: Christian Barry, Ben Caplan, and Hannah Moscovitch's Old Stock: A Refugee Love Story, Ryan Griffith's The Boat, and Xavier Gould‘s digital personality ―Jass-Sainte Bourque‖. Combining Ric Knowles' "dramaturgy of the perverse" (The Theatre of Form 1999) with Sara Ahmed's "queer phenomenology" (Queer Phenomenology 2006) allows for a thorough queer analysis of these three performances. I argue that such an approach positions new Atlantic Canadian performances and dramaturgies as sites of aesthetic and semantic disorientation. Building on Jill Dolan's "utopian performatives" (Utopia in Performance 2005), wherein the audiences experience a collective "lifting above" of normative dramaturgical structures, my use of "queer phenomenology" fosters a plurality of unique perspectives. -

Provincial Solidarities: a History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour

provincial solidarities Working Canadians: Books from the cclh Series editors: Alvin Finkel and Greg Kealey The Canadian Committee on Labour History is Canada’s organization of historians and other scholars interested in the study of the lives and struggles of working people throughout Canada’s past. Since 1976, the cclh has published Labour / Le Travail, Canada’s pre-eminent scholarly journal of labour studies. It also publishes books, now in conjunction with AU Press, that focus on the history of Canada’s working people and their organizations. The emphasis in this series is on materials that are accessible to labour audiences as well as university audiences rather than simply on scholarly studies in the labour area. This includes documentary collections, oral histories, autobiographies, biographies, and provincial and local labour movement histories with a popular bent. series titles Champagne and Meatballs: Adventures of a Canadian Communist Bert Whyte, edited and with an introduction by Larry Hannant Working People in Alberta: A History Alvin Finkel, with contributions by Jason Foster, Winston Gereluk, Jennifer Kelly and Dan Cui, James Muir, Joan Schiebelbein, Jim Selby, and Eric Strikwerda Union Power: Solidarity and Struggle in Niagara Carmela Patrias and Larry Savage The Wages of Relief: Cities and the Unemployed in Prairie Canada, 1929–39 Eric Strikwerda Provincial Solidarities: A History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour / Solidarités provinciales: Histoire de la Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Nouveau-Brunswick David Frank A History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour david fra nk canadian committee on labour history Copyright © 2013 David Frank Published by AU Press, Athabasca University 1200, 10011 – 109 Street, Edmonton, ab t5j 3s8 isbn 978-1-927356-23-4 (print) 978-1-927356-24-1 (pdf) 978-1-927356-25-8 (epub) A volume in Working Canadians: Books from the cclh issn 1925-1831 (print) 1925-184x (digital) Cover and interior design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design. -

A Comparative Study of French-Canadian and Mexican-American Contemporary Poetry

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF FRENCH-CANADIAN AND MEXICAN-AMERICAN CONTEMPORARY POETRY by RODERICK JAMES MACINTOSH, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN SPANISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY Approved Accepted May, 1981 /V<9/J^ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am T«ry grateful to Dr. Edmundo Garcia-Giron for his direction of this dissertation and to the other mem bers of my committee, Dr. Norwood Andrews, Dr. Alfred Cismaru, Dr. Aldo Finco and Dr. Faye L. Bianpass, for their helpful criticism and advice. 11 ' V^-^'s;-^' CONTENTS ACKNOWI£DGMENTS n I. k BRIEF HISTORY OF QUE3EC 1 II• A BRIEF HISTORY OF MEXICAN-AMERICANS ^9 III. A LITERARY HISTORY OF QUEBEC 109 IV. A BRIEF OUTLINE OF ^MEXICAN LITERATURE 164 7» A LITERARY HISTORY OF HffiXICAN-AT/lERICANS 190 ' VI. A COMPARATIVE LOOK AT CANADZkll FRENCH AND MEXICAN-AMERICAN SPANISH 228 VII- CONTEMPORARY PRSNCK-CANADIAN POETRY 2^7 VIII. CONTEMPORARY TffiCICAN-AMERICAN POETRY 26? NOTES 330 BIBLIOGRAPHY 356 111 A BRIEF HISTORY OF QUEBEC In 153^ Jacques Cartier landed on the Gaspe Penin sula and established French sovereignty in North America. Nevertheless, the French did not take effective control of their foothold on this continent until 7^ years later when Samuel de Champlain founded the settlement of Quebec in 1608, at the foot of Cape Diamond on the St. Laurence River. At first, the settlement was conceived of as a trading post for the lucrative fur trade, but two difficul ties soon becam,e apparent—problems that have plagued French Canada to the present day—the difficulty of comirunication across trackless forests and m.ountainous terrain and the rigors of the Great Canadian Winter. -

Birds of the Nova Scotia— New Brunswick Border Region by George F

Birds of the Nova Scotia— New Brunswick border region by George F. Boyer Occasional Paper Number 8 Second edition Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Environnement Canada Wildlife Service Service de la Faune Birds of the Nova Scotia - New Brunswick border region by George F. Boyer With addendum by A. J. Erskine and A. D. Smith Canadian Wildlife Service Occasional Paper Number 8 Second edition Issued under the authority of the Honourable Jack Davis, PC, MP Minister of the Environment John S. Tener, Director Canadian Wildlife Service 5 Information Canada, Ottawa, 1972 Catalogue No. CW69-1/8 First edition 1966 Design: Gottschalk-)-Ash Ltd. 4 George Boyer banding a barn swallow in June 1952. The author George Boyer was born in Woodstock, New Brunswick, on August 24, 1916. He graduated in Forestry from the University of New Brunswick in 1938 and served with the Canadian Army from 1939 to 1945. He joined the Canadian Wildlife Service in 1947, and worked out of the Sackville office until 1956. During that time he obtained an M.S. in zoology from the University of Illinois. He car ried on private research from April 1956 until July 1957, when he rejoined CWS. He worked out of Maple, Ontario, until his death, while on a field trip near Aultsville. While at Sackville, Mr. Boyer worked chiefly on waterfowl of the Nova Scotia-New Brunswick border region, with special emphasis on Pintails and Black Ducks. He also studied merganser- salmon interrelationships on the Miramichi River system, Woodcock, and the effects on bird popu lations of spruce budworm control spraying in the Upsalquitch area. -

Acadiens and Cajuns.Indb

canadiana oenipontana 9 Ursula Mathis-Moser, Günter Bischof (dirs.) Acadians and Cajuns. The Politics and Culture of French Minorities in North America Acadiens et Cajuns. Politique et culture de minorités francophones en Amérique du Nord innsbruck university press SERIES canadiana oenipontana 9 iup • innsbruck university press © innsbruck university press, 2009 Universität Innsbruck, Vizerektorat für Forschung 1. Auflage Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Umschlag: Gregor Sailer Umschlagmotiv: Herménégilde Chiasson, “Evangeline Beach, an American Tragedy, peinture no. 3“ Satz: Palli & Palli OEG, Innsbruck Produktion: Fred Steiner, Rinn www.uibk.ac.at/iup ISBN 978-3-902571-93-9 Ursula Mathis-Moser, Günter Bischof (dirs.) Acadians and Cajuns. The Politics and Culture of French Minorities in North America Acadiens et Cajuns. Politique et culture de minorités francophones en Amérique du Nord Contents — Table des matières Introduction Avant-propos ....................................................................................................... 7 Ursula Mathis-Moser – Günter Bischof des matières Table — By Way of an Introduction En guise d’introduction ................................................................................... 23 Contents Herménégilde Chiasson Beatitudes – BéatitudeS ................................................................................................. 23 Maurice Basque, Université de Moncton Acadiens, Cadiens et Cajuns: identités communes ou distinctes? ............................ 27 History and Politics Histoire -

Mise En Place D'un Dispositif Hybride Visant La Pratique De L'oral

Mise en place d’un dispositif hybride visant la pratique de l’oral asynchrone dans une université coréenne Boris Labianca To cite this version: Boris Labianca. Mise en place d’un dispositif hybride visant la pratique de l’oral asynchrone dans une université coréenne. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2016. dumas-01340122 HAL Id: dumas-01340122 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01340122 Submitted on 30 Jun 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Mise en place d’un dispositif hybride visant la pratique de l’oral asynchrone dans une université coréenne LABIANCA Boris Sous la direction de M. François MANGENOT UFR Langage, lettres et arts du spectacle, information et communication (LLASIC) Département Sciences du langage et français langue étrangère (FLE) Mémoire de master 2 professionnel - 30 crédits - Mention Sciences du langage Spécialité : Français Langue Etrangère Année universitaire 2015-2016 Mise en place d’un dispositif hybride visant la pratique de l’oral asynchrone dans une université coréenne LABIANCA Boris Sous la direction de M. François MANGENOT UFR Langage, lettres et arts du spectacle, information et communication (LLASIC) Département Sciences du langage et français langue étrangère (FLE) Mémoire de master 2 professionnel - 30 crédits - Mention Sciences du langage Spécialité : Français Langue Etrangère Année universitaire 2015-2016 Remerciements Je tiens à remercier mon directeur de mémoire, M. -

New Zealand Meets South Korea: Strategies for Film Co-Productions Between Two Countries

http://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. New Zealand meets South Korea: Strategies for film co-productions between two countries A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Screen and Media Studies Department at The University of Waikato by JuHee Kim Year of submission 2017 Abstract This study investigates the state of international film co-productions between New Zealand and South Korea and whether such co-productions are possible, and if so, which modes or types of film co-productions are likely to succeed. The study is framed in the context of the two countries as well as the rapidly changing global marketplace. Increasingly, international film co-productions have gained importance in the film industry paralleling a growing tendency towards cross- border filmmaking. However, the phenomenon of international film co- productions, specifically between New Zealand and South Korea, has not been fully investigated to date. -

2019 Spring/Summer Communication

2019 Spring/ Summer edition A message from the Editor Bonjour chères lectrices et chers lecteurs, I am delighted to introduce our members to the new Board of Directors for 2019-2020. This group of diverse professionals volunteer their time during the day, at night and on weekends to keep this association vibrant, current and serving the needs of their members in regards to FSL and International Languages in Ontario. Our association is proud to have a wonderful team of directors with a variety of teaching experiences, language backgrounds, and great strengths and from all over our province working on our collective behalf. I encourage you, our readers, to enhance your network and broaden your knowledge by actively using your OMLTA membership. Your membership provides you with free access to resources, leadership opportunities and discounted events. We encourage members to support networking and collaboration by contributing their expertise to our Communication; consider submitting ideas, strategies, resources or articles that support the modern language classroom. Also, this year we will be introducing our activity of the month where we welcome members from across the province to submit classroom strategies and tools to be featured on our website. Other exciting initiatives are being planned, so be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to keep informed. Je suis tellement fière de faire partie d’une équipe si travaillante et positive. Entrez en contact avec vos directrices/directeurs, venez nous connaitre cette année et profitez de votre adhésion. Suivez-nous sur les médias sociaux. Inscrivez-vous à une de nos conférences ou à un de nos événements. -

Calling All Cajuns!

CALLING ALL CAJUNS! A Publication of The Acadian Memorial Foundation March 2011 Saturday, March 19th 10 am - 4pm It’s festival time: Evangeline Blvd & S New Market St 7th Annual A quick mention about the special presentations we have Acadian Memorial Festival March 19, 2011 lined up for this year’s festival, honoring the families FREE ADMISSION Boudreaux and Guillotte: They’ll be honored during the 1 p.m. Reenactment of the Arrival of the Acadians. Evangeline Queen 9 am: CAFA meeting, AM Hall upstairs Maddison Bahry (Plaquemine’s 2010 International Acadian Festival) will be here. Don Arceneaux will speak about “18th 10 am: Opening ceremonies and flag raising: Gazebo & City Century Male and Female Boudreaux Immigration to Colonial Hall Porch Louisiana,” and “The Life of Francois Boudreaux.” Dr. Charles 10:30 am: Renaissance R. Brassieur will give a talk on “Les Vacheurs, The Cattle Cadienne Dance Troupe: Ranchers of the Marsh.” Ray Trahan has information to share Evangeline Blvd & S New about the GRA. Wooden boat enthusiasts will display and Market St. parade antique wooden pirogues, Putt Putts, and other “Old "Babineaux Fuselier Band.” 11 am: Cheri Armentor, Kids’ Time” water craft items. Don’t miss performances by Théâtre Gracie Babineaux, Julie Mardi Gras Theater: City Hall Babineaux, Scotty Cormier, Acadien, Renaissance Cadienne Dancers and the Babineaux Zachary Fuselier, & Mark 11 am-1 pm: The Babineaux Fuselier Band! Clara Darbonne, Kathy Mier and Cheri Comeaux Submitted photo Fuselier Cajun Band: corner of Evangeline Blvd & S New Mkt Armentor will be here too (see page 2 for more info)! 11:15 am: GRA Presentation by Ray Trahan: AM Hall upstairs Acadian memorial festival 2011: 11:30 am: Putt Putt Parade on Bayou Teche “Gearing up for GRA!” 11:45 am: Théâtre Acadien performs (in french): AM Hall Qu’est-ce que c’est, GRA? It’s the first ever Grand downstairs Réveil Acadien (Great Acadian Awakening), which is going 12 pm: Kathy Mier presents Kids’ Stories & Tintamarre: take place October 7-16 throughout South Louisiana. -

L U N C H E O N S M O R G Is B A

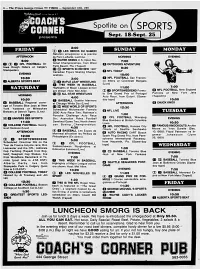

2 : 0 0 MONDAY FRIDAY (D G LES HEROS DU SAMEDI SUNDAY Natation enregistree a la piscine AFTERNOON du Parc LaSalle, Lachine. MORNING ‘ EVENING 5:00 Q WATER SKIING U S Open Na 7:00 tional Championships, from West O d lO C F L FOOTBALL Ot G OUTDOORS ADVENTURE tawa Rough Riders at Calgary Palm Beach. Fla. (Taped) 9:30 Stampeders (D © SPORTS IN REVIEW 1987 Canadian Figure Skating Champi O NFL TODAY EVENING onships. 1 0 : 0 0 10:30 3:00 O NFL FOOTBALL San Francis O ALBERTA SPORTS BEAT (D Q MAPLE LEAF WRESTLING co 49ers at Cincinnati Bengals O THIS WEEK IN BASEBALL (Live) SATURDAY Highlights of Major League action 1 1 : 0 0 7:00 are shown. Host: Mel Allen. © G SPORTSWEEKEND Formu O NFL FOOTBALL New England la One Grand Prix of Portugal Patriots at New York Jets MORNING (D © ALL-STAR WRESTLING 4:00 Auto Race, from Estoril. (Same- (Ta p e d )p 10:30 O BASEBALL Seattle Mariners day tape) 1 0 : 0 0 O BASEBALL Regional cover at Chicago White Sox (Live) AFTERNOON G CHUCK KNOX age of Toronto Blue Jays at New (D © WIDE WORLD OF SPORTS 12:30 York Yankees or Milwaukee Scheduled: Motomaster Formula Q NFL LIVE TUESDAY Brewers at Detroit Tigers. (Live) 2000 Auto Race Two; Rothman's 1 : 0 0 1 1 : 0 0 Porsche Challenge Auto Race ( 3 G UNI VERS DES SPORTS Six; Australian Rules Football G CFL FOOTBALL Winnipeg EVENING Semifinal Game Two; North Ameri Blue Bombers at British Columbia 11:30 Lions 10:30 O COLLEGE FOOTBALL Georg can Boxing Championships. -

Proquest Dissertations

University of Alberta L'Acadie communautaire: The Inclusion and Exclusion of New Brunswick Francophones by Christina Lynn Keppie © A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Modern Languages and Cultural Studies Edmonton, Alberta Fall 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-46343-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-46343-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation.