Next NB/Avenir N-B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provincial Solidarities: a History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour

provincial solidarities Working Canadians: Books from the cclh Series editors: Alvin Finkel and Greg Kealey The Canadian Committee on Labour History is Canada’s organization of historians and other scholars interested in the study of the lives and struggles of working people throughout Canada’s past. Since 1976, the cclh has published Labour / Le Travail, Canada’s pre-eminent scholarly journal of labour studies. It also publishes books, now in conjunction with AU Press, that focus on the history of Canada’s working people and their organizations. The emphasis in this series is on materials that are accessible to labour audiences as well as university audiences rather than simply on scholarly studies in the labour area. This includes documentary collections, oral histories, autobiographies, biographies, and provincial and local labour movement histories with a popular bent. series titles Champagne and Meatballs: Adventures of a Canadian Communist Bert Whyte, edited and with an introduction by Larry Hannant Working People in Alberta: A History Alvin Finkel, with contributions by Jason Foster, Winston Gereluk, Jennifer Kelly and Dan Cui, James Muir, Joan Schiebelbein, Jim Selby, and Eric Strikwerda Union Power: Solidarity and Struggle in Niagara Carmela Patrias and Larry Savage The Wages of Relief: Cities and the Unemployed in Prairie Canada, 1929–39 Eric Strikwerda Provincial Solidarities: A History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour / Solidarités provinciales: Histoire de la Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Nouveau-Brunswick David Frank A History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour david fra nk canadian committee on labour history Copyright © 2013 David Frank Published by AU Press, Athabasca University 1200, 10011 – 109 Street, Edmonton, ab t5j 3s8 isbn 978-1-927356-23-4 (print) 978-1-927356-24-1 (pdf) 978-1-927356-25-8 (epub) A volume in Working Canadians: Books from the cclh issn 1925-1831 (print) 1925-184x (digital) Cover and interior design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design. -

RS24 S1- S43 Introduction

The General Assembly of New Brunswick: Its History and Records The Beginnings The History The Records in Context The History of the Sessional Records (RS24) The Organization of the Sessional Records (RS24) A Note on Spellings Notes on Place Names List of Lieutenant-Governors and Administrators Guide to Sessional Records (RS24) on Microfilm 1 The Beginnings: On August 18, 1784, two months after the new province of New Brunswick was established, Governor Thomas Carleton was instructed by Royal Commission from King George III to summon and call a General Assembly. The steps taken by Governor Carleton in calling this assembly are detailed in his letter of October 25, 1785, to Lord Stanley in the Colonial Office at London: "My Lord, I have the honor to inform your Lordship that having completed such arrangements as appeared to be previously requested, I directed writs to issue on the 15th instant for convening a General Assembly to meet on the first Tuesday in January next. In this first election it has been thought advisable to admit all males of full age who have been inhabitants of the province for no less than three months to the privilege of voting, as otherwise many industrious and meritorious settlers, who are improving the lands allotted to them but have not yet received the King's Grant, must have been excluded. … The House of Representatives will consist of 26 members, who are chosen by their respective counties, no Boroughs or cities being allowed a distinct Representation. The county of St. John is to send six members, Westmorland, Charlotte, and York four members each, Kings, Queens, Sunbury and Northumberland, each two members. -

Famous New Brunswickers A

FAMOUS NEW BRUNSWICKERS A - C James H. Ganong co-founder ganong bros. chocolate Joseph M. Augustine native leader, historian Charles Gorman speed skater Julia Catherine Beckwith author Shawn Graham former premier Richard Bedford Bennett politician, Phyllis Grant artist philanthropist Julia Catherine Hart author Andrew Blair politician Richard Hatfield politician Winnifred Blair first miss canada Sir John Douglas Hazen politician Miller Brittain artist Jack Humphrey artist Edith Butler singer, songwriter John Peters Humphrey jurist, human Dalton Camp journalist, political rights advocate strategist I - L William "Bliss" Carman poet Kenneth Cohn Irving industrialist Hermenegilde Chiasson poet, playwright George Edwin King jurist, politician Nathan Cummings founder Pierre-Amand Landry lawyer, jurist consolidated foods (sara lee) Andrew Bonar Law statesman, british D - H prime minister Samuel "Sam" De Grasse actor Arthur LeBlanc violinist, composer Gordon "Gordie" Drillon hockey player Romeo LeBlanc politician, statesman Yvon Durelle boxing champion M Sarah Emma Edmonds union army spy Antonine Maillet author, playwright Muriel McQueen Fergusson first Anna Malenfant opera singer, woman speaker of the canadian senate composer, teacher Gilbert Finn politician Louis B. Mayer producer, co-founder Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (born in Russia) Gilbert Ganong co-founder ganong bros. chocolate Harrison McCain co-founder mccain Louis Robichaud politician foods Daniel "Dan" Ross author Wallace McCain co-founder mccain foods -

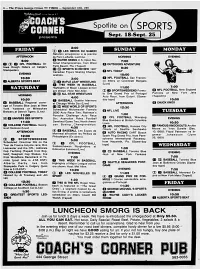

L U N C H E O N S M O R G Is B A

2 : 0 0 MONDAY FRIDAY (D G LES HEROS DU SAMEDI SUNDAY Natation enregistree a la piscine AFTERNOON du Parc LaSalle, Lachine. MORNING ‘ EVENING 5:00 Q WATER SKIING U S Open Na 7:00 tional Championships, from West O d lO C F L FOOTBALL Ot G OUTDOORS ADVENTURE tawa Rough Riders at Calgary Palm Beach. Fla. (Taped) 9:30 Stampeders (D © SPORTS IN REVIEW 1987 Canadian Figure Skating Champi O NFL TODAY EVENING onships. 1 0 : 0 0 10:30 3:00 O NFL FOOTBALL San Francis O ALBERTA SPORTS BEAT (D Q MAPLE LEAF WRESTLING co 49ers at Cincinnati Bengals O THIS WEEK IN BASEBALL (Live) SATURDAY Highlights of Major League action 1 1 : 0 0 7:00 are shown. Host: Mel Allen. © G SPORTSWEEKEND Formu O NFL FOOTBALL New England la One Grand Prix of Portugal Patriots at New York Jets MORNING (D © ALL-STAR WRESTLING 4:00 Auto Race, from Estoril. (Same- (Ta p e d )p 10:30 O BASEBALL Seattle Mariners day tape) 1 0 : 0 0 O BASEBALL Regional cover at Chicago White Sox (Live) AFTERNOON G CHUCK KNOX age of Toronto Blue Jays at New (D © WIDE WORLD OF SPORTS 12:30 York Yankees or Milwaukee Scheduled: Motomaster Formula Q NFL LIVE TUESDAY Brewers at Detroit Tigers. (Live) 2000 Auto Race Two; Rothman's 1 : 0 0 1 1 : 0 0 Porsche Challenge Auto Race ( 3 G UNI VERS DES SPORTS Six; Australian Rules Football G CFL FOOTBALL Winnipeg EVENING Semifinal Game Two; North Ameri Blue Bombers at British Columbia 11:30 Lions 10:30 O COLLEGE FOOTBALL Georg can Boxing Championships. -

Chapter 11 the Middle Years In

Spray & Rhinelander, History of St. Thomas University: The Formative Years 1860-1990 -- page 595 CHAPTER 11 THE MIDDLE YEARS IN FREDERICTON: ST. THOMAS 1975-1990 THE NEW PRESIDENCY The Martin Presidency The years 1975 to 1990 represented not only St. Thomas University's middle years in Fredericton but also its “Martin Years,” the period of the presidency of Rev. (Msgr. from 1985) George Martin. His presidency came as something of a respite from the tumultuous regime of Msgr. Donald Duffie, the president who preceded him at St. Thomas. Duffie had extracted St. Thomas from its old home in Chatham on the Miramichi and transplanted it to its new existence on the UNB campus in Fredericton, leaving it ten years later still in a relatively chaotic state consisting of recently-constructed buildings, a recently hired and fractious (and increasingly non-Catholic) faculty, an uncertain relationship with UNB, and indeed a tenuous or at least as-yet undefined position within the structure of post-secondary educational institutions in the province. Martin, who was no stranger to St. Thomas's situation, having officially been the university's registrar throughout Duffie's regime, spent the next decade and a half repairing relations with the faculty and embarking on an ambitious plan to carve out a special niche for St. Thomas among the province's other universities by creating new academic programmes. For all his modest assessment of his administrative abilities at the start, he proved to be an astute and talented constructor of a flexible Spray & Rhinelander, History of St. Thomas University: The Formative Years 1860-1990 -- page 596 institutional framework that not only took the university through its “middle period” in Fredericton but provided a basis for the complete modernization that followed under his successor presidents. -

Listening and Getting Things Done

from Speech the Throne Third session of the 58th Legislative Assembly of New Brunswick The Honourable Jocelyne Roy Vienneau, Lieutenant-Governor Listening and getting things done November 2, 2016 Speech from the Throne Third session of the 58th Legislative Assembly of New Brunswick Province of New Brunswick PO 6000, Fredericton NB E3B 5H1 CANADA www.gnb.ca ISBN 978-1- 4605-1156-5 (bilingual print edition) ISBN 978-1-4605-1157-2 (PDF: English edition) ISBN 978-1-4605-1158-9 (PDF: French edition) Cover photo: Hopewell Cape, Demoiselle Beach (Kevin Snair, Creative Imagery) 10858 | 2016.11 | Printed in New Brunswick Speech from the Throne 2016 General Opening Remarks Mr. Speaker, Honourable Members of the Legislative Assembly, invited guests and all New Brunswickers. Welcome to the opening of the Third Session of the 58th Legislative Assembly of the Province of New Brunswick. We are now just past the midway point of this current government’s mandate. This government has listened closely to the concerns of the people of this great province. New Brunswickers have provided this government with guidance by bringing many ideas to the table that will help improve this province and the lives of our residents. Your government recognizes that New Brunswickers expect their leaders to listen to their concerns, understand their needs, and then deliver results. This has been the approach of your government. Your government understands that New Brunswickers want more economic growth and a stronger health care system. To accomplish economic growth and a vibrant health care system your government’s main focus over the next year will be education. -

This Week in New Brunswick History

This Week in New Brunswick History In Fredericton, Lieutenant-Governor Sir Howard Douglas officially opens Kings January 1, 1829 College (University of New Brunswick), and the Old Arts building (Sir Howard Douglas Hall) – Canada’s oldest university building. The first Baptist seminary in New Brunswick is opened on York Street in January 1, 1836 Fredericton, with the Rev. Frederick W. Miles appointed Principal. Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) becomes responsible for all lines formerly January 1, 1912 operated by the Dominion Atlantic Railway (DAR) - according to a 999 year lease arrangement. January 1, 1952 The town of Dieppe is incorporated. January 1, 1958 The city of Campbellton and town of Shippagan become incorporated January 1, 1966 The city of Bathurst and town of Tracadie become incorporated. Louis B. Mayer, one of the founders of MGM Studios (Hollywood, California), January 2, 1904 leaves his family home in Saint John, destined for Boston (Massachusetts). New Brunswick is officially divided into eight counties of Saint John, Westmorland, Charlotte, Northumberland, King’s, Queen’s, York and Sunbury. January 3, 1786 Within each county a Shire Town is designated, and civil parishes are also established. The first meeting of the New Brunswick Legislature is held at the Mallard House January 3, 1786 on King Street in Saint John. The historic opening marks the official business of developing the new province of New Brunswick. Lévite Thériault is elected to the House of Assembly representing Victoria January 3, 1868 County. In 1871 he is appointed a Minister without Portfolio in the administration of the Honourable George L. Hatheway. -

Ring Magazine

The Boxing Collector’s Index Book By Mike DeLisa ●Boxing Magazine Checklist & Cover Guide ●Boxing Films ●Boxing Cards ●Record Books BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK INSERT INTRODUCTION Comments, Critiques, or Questions -- write to [email protected] 2 BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK INDEX MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS Ring Magazine Boxing Illustrated-Wrestling News, Boxing Illustrated Ringside News; Boxing Illustrated; International Boxing Digest; Boxing Digest Boxing News (USA) The Arena The Ring Magazine Hank Kaplan’s Boxing Digest Fight game Flash Bang Marie Waxman’s Fight Facts Boxing Kayo Magazine World Boxing World Champion RECORD BOOKS Comments, Critiques, or Questions -- write to [email protected] 3 BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK RING MAGAZINE [ ] Nov Sammy Mandell [ ] Dec Frankie Jerome 1924 [ ] Jan Jack Bernstein [ ] Feb Joe Scoppotune [ ] Mar Carl Duane [ ] Apr Bobby Wolgast [ ] May Abe Goldstein [ ] Jun Jack Delaney [ ] Jul Sid Terris [ ] Aug Fistic Stars of J. Bronson & L.Brown [ ] Sep Tony Vaccarelli [ ] Oct Young Stribling & Parents [ ] Nov Ad Stone [ ] Dec Sid Barbarian 1925 [ ] Jan T. Gibbons and Sammy Mandell [ ] Feb Corp. Izzy Schwartz [ ] Mar Babe Herman [ ] Apr Harry Felix [ ] May Charley Phil Rosenberg [ ] Jun Tom Gibbons, Gene Tunney [ ] Jul Weinert, Wells, Walker, Greb [ ] Aug Jimmy Goodrich [ ] Sep Solly Seeman [ ] Oct Ruby Goldstein [ ] Nov Mayor Jimmy Walker 1922 [ ] Dec Tommy Milligan & Frank Moody [ ] Feb Vol. 1 #1 Tex Rickard & Lord Lonsdale [ ] Mar McAuliffe, Dempsey & Non Pareil 1926 Dempsey [ ] Jan -

L'assemblée Législative Du Nouveau-Brunswick À L'ère Du XXI Siècle

L’Assemblée législative du Nouveau-Brunswick à l’ère du XXIe siècle Donald Desserud, Institut des études urbaines et communautaires Stewart Hyson, Département d’histoire et de sciences politiques Université du Nouveau-Brunswick (campus de Saint John) Saint John (Nouveau-Brunswick) E2L 4L5 Courriels : [email protected] et [email protected] Produit pour le Groupe canadien d’étude des parlements, Ottawa, 20111 Groupe canadien d’étude des parlements Introduction Lorsque le Nouveau-Brunswick est entré dans la Confédération, en 1867, les fondations du modèle de Westminster de démocratie législative (à savoir un gouvernement représentatif et responsable) étaient déjà en place. De telles institutions étaient typiques dans les colonies britanniques de l’époque, caractérisées par un électorat relativement restreint, une activité gouvernementale de portée limitée et des méthodes de prise de décisions élitistes. Toutefois, si les institutions parlementaires et la culture politique d’autres anciennes colonies britanniques ont évolué de la fin du XIXe siècle au début du XXe siècle, il semble que le Nouveau-Brunswick, lui, se soit figé dans le temps. Au sujet de la propension au clientélisme et à la corruption dans la province, Patrick Fitzpatrick a écrit, en 1972, qu’on pourrait décrire la politique provinciale au Nouveau-Brunswick comme fermée, stagnante et anachronique et qu’elle rappelle, sous certains abords, la politique qui avait cours au XIXe siècle en Grande-Bretagne avant le mouvement de réforme (116; voir également Doyle, 1976, et Thorburn, 1961). Quoi qu’il en soit, les bases de la réforme avaient déjà été jetées. Les années 1960, en particulier, ont été balayées par de grands changements sur le plan de la gouvernance, des services sociaux, de l’éducation et de la redistribution des revenus, grâce au programme visionnaire « Chances égales pour tous » du premier ministre libéral Louis Robichaud, au pouvoir de 1960 à 1970 (Stanley, 1984; Young, 1986, 1987; ICRDR, 2001; Cormier, 2004). -

Maps of Upper St. John and Madawaska Rivers in 1778 and Land Requested by the Natives and Kelly’S Lot, 1787 from Library and Archives Canada MCC-00502

Maps of Upper St. John and Madawaska Rivers in 1778 and land requested by the Natives and Kelly’s lot, 1787 from Library and Archives Canada MCC-00502 Finding Aid Prepared by Anne Chamberland, March 2021 Acadian Archives/Archives acadiennes University of Maine at Fort Kent Fort Kent, Maine Title: Maps of Upper St. John and Madawaska Rivers in 1778 and land requested by the Natives and Kelly’s lot, 1787 from Library and Archives Canada Creator/Collector: Library and Archives Canada Collection number: MCC-00502 Shelf list number: K-502 (cylinder) Dates: 1778 & 1787 Extent: 1 map tube (0.35 cubic feet) Provenance: Material was bought on Compact Disc format from Library and Archives Canada in 2010. Language: English Conservation notes: Maps were printed on vinyl for exhibit Access restrictions: No restrictions on access. Physical restrictions: None. Technical restrictions: None. Copyright: Copyright has not been assigned to the Acadian Archives/Archives acadiennes. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Acadian Archives/Archives acadiennes Citation: Maps of Upper St. John and Madawaska Rivers in 1778 and land requested by the Natives and Kelly’s lot, 1787 from Library and Archives Canada, MCC-00502, Acadian Archives/Archives acadiennes, University of Maine at Fort Kent. Separated materials: Not applicable. Related materials: Not applicable. Location of originals: Library and Archives Canada Location of copies: Not applicable. Published in: Not applicable. Biographical information: SPROULE (Sprowle), GEORGE, army officer, surveyor, office holder, and politician; b. c. 1743 in Athlone (Republic of Ireland), eldest son of Adam Sproule and Prudence Lloyd; d. -

Revolutionary New Hampshire and the Loyalist Experience: "Surely We Have Deserved a Better Fate"

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 1983 REVOLUTIONARY NEW HAMPSHIRE AND THE LOYALIST EXPERIENCE: "SURELY WE HAVE DESERVED A BETTER FATE" ROBERT MUNRO BROWN Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation BROWN, ROBERT MUNRO, "REVOLUTIONARY NEW HAMPSHIRE AND THE LOYALIST EXPERIENCE: "SURELY WE HAVE DESERVED A BETTER FATE"" (1983). Doctoral Dissertations. 1351. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1351 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. -

The Florida Society of the Sons of the American Revolution Fort Lauderdale Chapter Newsletter

The Florida Society of the Sons of the American Revolution Fort Lauderdale Chapter Newsletter website: www.learnwebskills.com/sar/index.html MAR 2012 Fort Lauderdale Chapter chartered December 8, 1966 Volume 45 Number 3 President’s Message Dear Compatriots: We had an enjoyable February meeting. The highlights of the meeting included a presentation by Florida DAR State Lineage Research Chairman, Dr. Debbie Duay on various hereditary societies that SAR members might be eligible to join, as well as a celebration of Compatriot George Dennis’ 98 th birthday complete with cake and a champagne toast. Those who could not attend the meeting missed a real treat. At the meeting, the members voted on a few items of Debbie Duay is presented a Certificate of Appreci- business. First, as Compatriot Jim Lohmeyer was ap- ation for her presentation at our February meeting. proved to be SAR’s representative to the local Veteran’s Clinic, $100 was allocated to him for the year for the purchase of coffee, donuts, and any other items needed for joint activities at the clinic for the benefit of the veterans. Second, the monthly chapter newsletter will now be mailed to all members instead of being electron- ically sent by e-mail, as there was concern that not all members were receiving the electronic version and were missing out on chapter news. Third, it was decided that our April meeting would be at the Seawatch Restaurant in Lauderdale By the Sea. The Seawatch restaurant has a great menu and a phenomenal view of the ocean. It is hoped that a change in meeting location will encourage Certificates of Appreciation were presented to our more members to attend.