1-Ancestry and Early Years (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE HISTORY of GERMANY T H E U N Co Mm E N Do N E Pope , Thro Gh His Talented Uncio , , Made Several Extremely Touch I Ng Representations to the Assembly

T HE HIST O R Y O F GE R MA N Y PA R T X v l l WAR O F: L IBE R AT IO N IN T HE N E T HE R L A N D S Pre o n der an ce o the S an ia rds an d CXCVIII . p f p — Jes uits Co ur tly Vic es HE false peace co ncluded at A ugsb urg was imm e di ’ T ately followed by Charles V . s abdication of his nu r o m e ro us c o wns . He w uld willingly have resigned m r h that of the e pi e to his son Philip , had not the Spanis o r o o m o educati n of that p ince , his gl y and big ted character, inspired the Germans with an aversi o n as un c o nque rable as h . m o r o t at with which he beheld them Ferdinand had , e ver, o r n . r n e e rt he gained the fav of the Germa princes Cha les , v f o so n o o less , influenced by a fection t ward his , best wed up n h im m o N one of the finest of the Ger an pr vinces , the ether W lands , besides Spain , Milan , Naples , and the est Indies r m (Am erica) . Fe dinand received the rest of the Ger an o o m hereditary possessi ns of his h use , besides Bohe ia and r r Hungary . -

A History of German-Scandinavian Relations

A History of German – Scandinavian Relations A History of German-Scandinavian Relations By Raimund Wolfert A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Raimund Wolfert 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Table of contents 1. The Rise and Fall of the Hanseatic League.............................................................5 2. The Thirty Years’ War............................................................................................11 3. Prussia en route to becoming a Great Power........................................................15 4. After the Napoleonic Wars.....................................................................................18 5. The German Empire..............................................................................................23 6. The Interwar Period...............................................................................................29 7. The Aftermath of War............................................................................................33 First version 12/2006 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations This essay contemplates the history of German-Scandinavian relations from the Hanseatic period through to the present day, focussing upon the Berlin- Brandenburg region and the northeastern part of Germany that lies to the south of the Baltic Sea. A geographic area whose topography has been shaped by the great Scandinavian glacier of the Vistula ice age from 20000 BC to 13 000 BC will thus be reflected upon. According to the linguistic usage of the term -

'This Thing's for Real'

The Westfield NewsSearch for The Westfield News Westfield350.com The WestfieldNews Serving Westfield, Southwick, and surrounding Hilltowns “TIME IS THE ONLY WEATHER CRITIC WITHOUT TONIGHT AMBITION.” Partly Cloudy. JOHN STEINBECK Low of 55. www.thewestfieldnews.com VOL. 86 NO. 151 $1.00 THURSDAY,TUESDAY, DECEMBER JUNE 27, 2017 17, 2020 VOL. 75 cents 89 NO. 302 Southwick Gov. Baker: schools keeping ‘This thing’s ‘Snow Days’ for real’ By HOPE E. TREMBLAY Editor SOUTHWICK – The Southwick- Tolland-Granville Regional School Residents urged Committee has not changed its “Snow Day” policy and when a snow day is declared, there will be no in-person or not to gather remote learning. Superintendent Jennifer C. Willard said Dec. 15 that with the pending for holidays snowstorm this week, many families By HOPE E. TREMBLAY were asking if there would be snow Editor days. BOSTON – Gov. Charlie D. Baker Dec. 15 implored “We’re going forward with good, It’s Santa! Massachusetts residents to remain vigilant in the fight old-fashioned snow days,” she said Above, Aurora Thielen hands letters to Santa to one of Santa’s helpers at against COVID-19 and to learn from the post-Thanks- during the regional School Committee Sunday’s drive-by event held by the Pottery Cellar. The Pottery Cellar at Mill at giving spike and stay home for the holidays. meeting Tuesday. Crane Pond hosted a drive-by Santa event Dec. 13. Children left letters for Baker, along with Secretary of Health and Human Some neighboring communities Santa and enjoyed hot cocoa and donuts. Collections were also taken for the Services Marylou Sudders and Massachusetts General have created a COVID policy and food pantry. -

Archbp. = Archbishop/Archbishopric; B

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88909-4 - German Histories in the Age of Reformations, 1400-1650 Thomas A. Brady Index More information Index Abbreviations: archbp. = archbishop/archbishopric; b. = born; bp. = bishop/bishopric; d. = died; r. = reigned/ruled Aachen, 89, 207, 252, 303, 312 Albert V ‘‘the Magnanimous’’ (b. 1528,r. absolutism, 7. See also European imperial 1550–79), duke of Bavaria, 294 nation-state Albert ‘‘the Stout-hearted’’ (1443–1500), duke academies: Bremen, 253; Herborn, 253, 279 of Saxony, 244 Acceptance of Mainz, 92n13 Albertine Saxony. See Saxony, Albertine acculturation, 289n101 Alcala´de Henares (Castile), 210 accumulation, benefices, 57n25 Alexander VI (r. 1492–1503), pope, 144 Adalbero (d. 1030), bp. of Laon, 29–30, 34, 49 Alexander VII (r. 1655–67), pope, 401n83, 410 Admont, abbey (Styria), 81 Alfonso I (b. 1396,r.1442–58), king of Naples, Adrian VI (r. 1522–23), pope, 145n63, 208 93 AEIOU, 91 Allga¨u, 193 Agnes (1551–1637), countess of Mansfeld- alliances, confessional: Catholics 1525, 215; Eisleben, 365 League of Gotha 1526, 215; Protestants 1529, Agricola, Gregor, pastor of Hatzendorf 216; Swiss cities with Strasbourg and Hesse (Styria), 344 1530, 217. See also Smalkaldic League Agricola, Johannes (1494–1566), 39 Alsace, 18, 23, 190; religious wars, 239; Swabian agriculture, 31 War, 119 Agrippa of Nettesheim, Cornelius (1486–1535), Alt, Salome (1568–1633), domestic partner of 54n10 Archbp. Wolf Dietrich von Raitenau, 306 Ahausen (Franconia), 368 Alte Veste, battle 1632, 382 Alba, duke of, Francisco Alvarez de Toledo Altenstetter, David (1547–1617), goldsmith of (1507–82), 238n41, 250n80 Augsburg, 332 Alber, Erasmus (1500–53), 264, 281 Alto¨ tting, shrine (Bavaria), 286 Albert (b. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI film s the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough* substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproductioiL In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these wül be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Nnsaber 9816176 ‘‘Ordo et lîbertas”: Church discipline and the makers of church order in sixteenth century North Germany Jaynes, JefiErey Philip, Ph.D. -

Vauban!S Siege Legacy In

VAUBAN’S SIEGE LEGACY IN THE WAR OF THE SPANISH SUCCESSION, 1702-1712 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jamel M. Ostwald, M.A. The Ohio State University 2002 Approved by Dissertation Committee: Professor John Rule, Co-Adviser Co-Adviser Professor John Guilmartin, Jr., Co-Adviser Department of History Professor Geoffrey Parker Professor John Lynn Co-Adviser Department of History UMI Number: 3081952 ________________________________________________________ UMI Microform 3081952 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ____________________________________________________________ ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ABSTRACT Over the course of Louis XIV’s fifty-four year reign (1661-1715), Western Europe witnessed thirty-six years of conflict. Siege warfare figures significantly in this accounting, for extended sieges quickly consumed short campaign seasons and prevented decisive victory. The resulting prolongation of wars and the cost of besieging dozens of fortresses with tens of thousands of men forced “fiscal- military” states to continue to elevate short-term financial considerations above long-term political reforms; Louis’s wars consumed 75% or more of the annual royal budget. Historians of 17th century Europe credit one French engineer – Sébastien le Prestre de Vauban – with significantly reducing these costs by toppling the impregnability of 16th century artillery fortresses. Vauban perfected and promoted an efficient siege, a “scientific” method of capturing towns that minimized a besieger’s casualties, delays and expenses, while also sparing the town’s civilian populace. -

Ships of Church and State in the Sixteenth-Century Reformation and Counterreformation: Setting Sail for the Modern State

MWP – 2014/05 Max Weber Programme Ships of Church and State in the Sixteenth-Century Reformation and Counterreformation: Setting Sail for the Modern State AuthorStephan Author Leibfried and and Author Wolfgang Author Winter European University Institute Max Weber Programme Ships of Church and State in the Sixteenth-Century Reformation and Counterreformation: Setting Sail for the Modern State Stephan Leibfried and Wolfgang Winter Max Weber Lecture No. 2014/05 This text may be downloaded for personal research purposes only. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper or other series, the year, and the publisher. ISSN 1830-7736 © Stephan Leibfried and Wolfgang Winter, 2014 Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Abstract Depictions of ships of church and state have a long-standing religious and political tradition. Noah’s Ark or the Barque of St. Peter represent the community of the saved and redeemed. However, since Plato at least, the ship also symbolizes the Greek polis and later the Roman Empire. From the fourth century ‒ the Constantinian era ‒ on, these traditions merged. Christianity was made the state religion. Over the course of a millennium, church and state united in a religiously homogeneous, yet not always harmonious, Corpus Christianum. In the sixteenth century, the Reformation led to disenchantment with the sacred character of both church and state as mediators indispensible for religious and secular salvation. -

A Short History of Germany

CTV » |-aill|||lK-4JJ • -^ V •^ VmOO^* «>^ "^ * ©IIS * •< f I * '^ *o • ft *0 * •J' c*- ^oV^ . "^^^O^ 4 o » 3, 9 9^ t^^^ 5^. ^ L^' HISTORY OF GERMANY. A SHORT HISTORY OF GERMANY BY Mrs. H. C. HAWTREY WITH ADDITIONAL CHAPTERS BY AMANDA M. FLATTERY 3 4i,> PUBLISHED FOR THE BAY VIEW READING CLUB Central Office, 165 Boston Boulevard DETROIT, MICH. 1903 iTI --0 H^ THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS. Two Copies Received JUL to 1903 •J Copyrigiil Entry Buss OL XXc N» COPY B. Copyright, 1903, by LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO. r t" t KOBERT DRUMMOND, PRINTER, NEW YORK. PREFACE. It would be absurd to suppose that a History of Germany could be written within the compass of 300 pages. The merest outline is all that could be given in this little book, and very much of vast interest and im- portance has necessarily been omitted. But some knowledge of the political events of former days is necessary for all persons—more especially trav- ellers—who desire to understand and appreciate the customs, buildings, paintings, etc., of any country, and it is hoped that short continental histories may be useful to many who have not time or opportunity for closer study. My aim in the present volume has been simply to give one marked characteristic of each King or Emperor's reign, so as to fix it in the memory; and to show how Prussia came to hold its present position of importance amongst the continental powers of Europe. Emily Hawtrey. iiL BOOK I. HISTORY OF GERMANY. INTRODUCTION. CHAPTER I. The mighty Teutonic or German race in Europe did not begin to play its part in history until the decline of the Roman Empire ; but we must all of us feel the warm- est interest in it when it does begin, for it represents not only the central history of Europe in the Middle Ages, but also the rise of our own forefathers in their home and birthplace of Germany. -

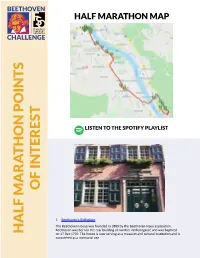

Half Mara Thon Points of Interest

HALF MARATHON MAP LISTEN TO THE SPOTIFY PLAYLIST OF INTEREST 1. Beethoven’s Birthplace The Beethoven House was founded in 1889 by the Beethoven-Haus association. Beethoven was born in the rear building at number 20 Bonngasse and was baptized HALF MARATHON POINTS HALF MARATHON on 17 Dec 1770. The house is now serving as a museum and cultural institution and is considered as a memorial site. 2. The Name of Jesus Church Located in the heart of Bonn city center - between the market and the Beethoven House - the Namen-Jesu-Kirche has been an important place of prayer, remembrance and worship for many Bonn families for three centuries. 3. The Sterntor City Gate The Sterntor City Gate at the edge of Bottlerplatz provides reminders of Bonn’s fortifications in the Middle Ages. It consists of the remainder of Bonn’s old city wall and observers can imagine how imposing the city fortifications must have been in the Middle Ages. 4. Beethoven-Denkmal This large bronze statue of Ludwig van Beethoven, which stands OF INTEREST on the Münsterplatz, was created on the 75th birth anniversary of his birth. The Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV, Queen Victoria of England and Alexander von Humboldt attended its inauguration in 1845. HALF MARATHON POINTS HALF MARATHON 5. Bonner Münster Also in the Münsterplatz square is a large Catholic church, the Bonner Münster. This was formerly the house of the Privy Councilor von Breuning of the German Order of Knights. In 1777, he lost his life in the fire at the electoral prince’s palace. -

Matters of Taste: the Politics of Food and Hunger in Divided Germany 1945-1971

Matters of Taste: The Politics of Food and Hunger in Divided Germany 1945-1971 by Alice Autumn Weinreb A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2009 Doctoral Committee: Professor Kathleen M. Canning, Co-Chair Associate Professor Scott D. Spector, Co-Chair Professor Geoff Eley Associate Professor Alaina M. Lemon Acknowledgements The fact that I would become a German historian had never crossed my mind ten years ago – that the past decade has made me one is entirely due to the remarkable number of people who have helped me in ways that even now I cannot fully grasp. Nonetheless, I suppose that these acknowledgements are as good a place as any to start a lifetime's worth of thanking. It all began at Columbia, where Professor Lisa Tiersten suggested that I go abroad, a suggestion that sent me for the first time to Germany. Five years later, when I first considered going to graduate school, she was the person I turned to for advice; her advice, as always, was excellent – and resulted in my becoming a German historian. During my first chaotic and bizarre years in Berlin, Professors Christina von Braun and Renate Brosch went out of their way to help a confused and hapless young American integrate herself into Humboldt University and get a job to pay the admittedly ridiculously low rent of my coal-heated Kreuzberg apartment. Looking back, it still amazes me how their generosity and willingness to help completely transformed my future. -

Castles and Palaces on the Romantic Rhine

Castles and Palaces on the Romantic Rhine Legendary! On the romantic Rhine, there is a castle landscape which is unique in its density and variety. Between Bingen and Rüdesheim in the south and the Siebengebirge (Seven Hills) in the north, mediaeval knights’ castles, pretty Baroque palaces and impressive fortifi cations unite to make up a unique cultural landscape. The va- riety of the buildings from various epochs is impressive: in this respect, some castles served to levy customs and were therefore important income sources for those in power. Other buildings on the other hand were constructed as safeguards against neighbouring archbishoprics or electorates and yet others fulfi lled purely representative functions. How the scores of castles and palaces on the romantic Rhine appear today could also hardly be more varied. Some of them have remained preserved over the centuries through elaborate restoration and accommodate restaurants, hotels or museums. Others radiate the mystic charm of (almost) crumbled ruins and one can only divine how many wars and revolts they have seen come and go. The count- less palaces, castles and ruins can be ideally experienced on foot, by bike or by ship on the Rhine and in the secondary valleys of the Rhine valley. The historical showpieces and weathered monuments are often linked by hiking paths. And it’s all the same whether they’re in ruined or restored condition: adventurous legends, often based on true facts, are entwined around many of the historical walls... it’s simply legendary! www.romantischer-rhein.de Mäuseturm (Mouse Tower), Bingen Klopp Castle, Bingen The Mouse Tower in Binger Loch is located on an inacces- Klopp Castle, founded in the middle of the 13th century by sible island and is, next to Pfalzgrafenstein Castle, the only the Archbishop of Mainz, Siegfried III, in Bingen, secured the defence tower and watch tower in the middle of the Rhine. -

Ottoman Conquests and European Ecclesiastical Pluralism

IZA DP No. 1973 Ottoman Conquests and European Ecclesiastical Pluralism Murat Iyigun DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES DISCUSSION PAPER February 2006 Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Ottoman Conquests and European Ecclesiastical Pluralism Murat Iyigun University of Colorado, Sabanci University and IZA Bonn Discussion Paper No. 1973 February 2006 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 Email: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of the institute. Research disseminated by IZA may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit company supported by Deutsche Post World Net. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its research networks, research support, and visitors and doctoral programs. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA Discussion Paper No. 1973 February 2006 ABSTRACT Ottoman Conquests and European Ecclesiastical Pluralism* This paper emphasizes that the evolution of religious institutions in Europe was influenced by the expansionary threat posed by the Ottoman Empire five centuries ago.