INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kreisverwaltung

Info Kreisverwaltung 1 Vogelsbergkreis – Der Kreisausschuss – Goldhelg 20 – 36341 Lauterbach/Hessen Telefon: 06641 977-0 – Fax 977-336 – [email protected] – Ausgabe 2009 www.vogelsbergkreis.de vermeiden – verwerten – entsorgen Dienstleistungsfirma ZAV Wir sind für Sie da… und wohin mit dem …wenn es um die umwelt- abfall? gerechte Abfall-Entsorgung geht. Bevor wir uns fragen, wohin mit dem Abfall, müssen wir uns eigentlich fragen, woher kommt denn der Abfall? Mit ca. 150 kg bis 350 kg Abfällen pro Einwohner im Jahr trägt der Verbrau- cher ganz wesentlich zum Müllberg bei. Letztendlich entschei- det jeder Einzelne von uns durch sein Kaufverhalten über die Abfallproduktion. Die Müllsortierung ist ein wichtiger Schritt, um Rohstoffe zu sparen, doch wer es mit dem Umweltschutz ernst nimmt, darf den Müll gar nicht erst entstehen lassen. Regie- rung, Produzenten und Verbraucher sind gleichermaßen aufge- fordert, zu einer nachhaltigen Wirtschaftsweise beizutragen. Verbraucher unterschätzen oftmals ihren Einfluß auf den Markt. Produkte, die nicht gekauft werden, werden bald nicht mehr haben Sie fragen zum abfall hergestellt. Überlegen Sie deshalb bei jedem Einkauf: Brauche ich dieses Produkt überhaupt? Kann ich auf eine Alternative und zur entsorgung im ausweichen, die umweltfreundlicher und abfallärmer ist? Gibt vogelsbergkreis? es ein vergleichbares Produkt, das länger hält, sich besser reparieren oder wiederverwenden läßt? wir sind für sie da! Versuchen Sie, bewusst Abfall zu vermeiden, indem Sie die Ver- meidungsangebote wie Mehrweg-, Nachfüllprodukte und recy- celbare Verpackungen aus Glas, Metall und Papier bevorzugen. Was Sie darüber hinaus aber noch tun können und wie Sie unvermeidbare Abfälle richtig entsorgen, erfahren Sie aus dem eselswörth 23 Abfallratgeber des Zweckverbandes Abfallwirtschaft Vogels- bergkreis (ZAV). -

Sla Ver Y Hinterlandb

SLAVERY HINTERLAND SLAVERY COVER ILLUSTRATIONS Front: Linen bleaching on the banks of the Wupper, ca 1800 (J.H. Bleuler) With permission of Bergischer Geschichtsverein, Bielefeld Back: Vriesenburg Plantation, Suriname Collection Kenneth Boumann (with permission) BRAHM, ROSENHAFT (EDS) ROSENHAFT BRAHM, SLAVERY HINTERLAND explores a neglected aspect of transatlantic slavery: the implication of a continental European hinterland. It focuses on Transatlantic Slavery and historical actors in territories that were not directly involved in the traffic in Africans but linked in various ways with the transatlantic slave business, Continental Europe, 1680-1850 the plantation economies that it fed and the consequences of its abolition. The volume unearths material entanglements of the Continental and Atlantic economies and also proposes a new agenda for the historical study of the relationship between business and morality. Contributors from the US, Britain EDITED BY FELIX BRAHM AND EVE ROSENHAFT and continental Europe examine the ways in which the slave economy touched on individual lives and economic developments in German-speaking Europe, Switzerland, Denmark and Italy. They reveal how these ‘hinterlands’ served as suppliers of investment, labour and trade goods for the slave trade and of materials for the plantation economies, and how involvement in trade networks contributed in turn to key economic developments in the ‘hinterlands’. The chapters range in time from the first, short-lived attempt at establishing a German slave-trading operation in the 1680s to the involvement of textile manufacturers in transatlantic trade in the first quarter of the nineteenth century. A key theme of the volume is the question of conscience, or awareness of being morally implicated in an immoral enterprise. -

Naturschutz Aktuell 169-187 Naturschutz Aktuell Zusammengestellt Von W

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Vogelkundliche Hefte Edertal Jahr/Year: 1987 Band/Volume: 13 Autor(en)/Author(s): Lübcke Wolfgang Artikel/Article: Naturschutz aktuell 169-187 Naturschutz aktuell zusammengestellt von W. Lübcke Kurz_notiert Allendorf: Erfolgreich zur Wehr setzte sich die HGON gegen die von der Gemeinde Allendorf geplante Asphaltierung eines Feldwe ges durch die Ederauen von Rennertehausen. (FZ v. 7* u. 8.1.86) 1984 waren die Feuchtwiesen durch einen Vertrag zwischen BFN und dem Wasser- und Bodenverband Rennertehausen gesichert wor den. (Vergl. Vogelk. Hefte 11 (1985) Bad Wildungen: Die Nachfolge von Falko Emde (Bad Wildungen) als Leiter des Arbeitskreises Waldeck-Frankenberg der HGON trat Harmut Mai (Wega) an. Sein Stellvertreter wurde Bernd Hannover (Lelbach). Schriftführer bleibt Karl Sperner (Wega). (WA vom 11.1.86) Bad Wildungen: Gegen die Zerstörung von Biotopen als "private Fortsetzung der Flurbereinigung" protestierte die DBV-Gruppe Bad Wildungen. Gravierendstes Beispiel ist die Dränierung der Feucht wiesen im Dörnbachtal bei Odershausen. (WLZ v. 14.1.86) Frankenau-Altenlotheim: Ohne Baugenehmigung entstand ein Reit platz in einem Feuchtwiesengelände des Lorfetales. U. a. wurde die Maßnahme durch Kreismittel bezuschußt. Im Rahmen eines Land schaftsplanes sollen Ersatzbiotope geschaffen werden. (WLZ v. 19.3.86) Volkmarsen: Verärgert zeigte sich die Stadt Volkmarsen über die NSG-Verordnung für den Stadtbruch (WLZ v. 20.3- u. 24.7.86). Ein Antrag auf Novellierung der VO wurde von der Obersten Natur- schutzbehörde abgelehnt. Rhoden: Einen Lehrgang zum Thema "Lebensraum Wald" veranstalte te der DBV-Kreisverband vom 20. bis 22. Juni 1986 in der Wald arbeiterschule des FA Diemelstadt. -

Machbarkeitsstudie Nordkreiskommunen 23062020

23.6.2020 KOMMUNEN CÖLBE MACHBARKEITSSTUDIE : „V ERTIEFTE LAHNTAL MÜNCHHAUSEN INTE RKOMMUNALE ZUSAMMENARBEIT “ WETTER Komprax Result: Carmen Möller | Machbarkeitsstudie: „Vertiefte interkommunale Zusammenarbeit“ Inhalt 1 Präambel ....................................................................................................................................... 14 2 Zusammenfassende Ergebnisse .................................................................................................... 15 3 Anlass und Auftrag ........................................................................................................................ 16 3.1 Beschlüsse der Gemeindevertretungen / Stadtverordnetenversammlung .......................... 16 3.2 Beauftragung ......................................................................................................................... 17 3.3 Projektorganisation ............................................................................................................... 17 3.4 Mitarbeiterbeteiligung .......................................................................................................... 20 3.5 Zeitplan .................................................................................................................................. 20 3.6 Fördermittel für die Studienerstellung .................................................................................. 22 4 Ausgangslage ................................................................................................................................ -

Interkommunale Kooperationen: Interkommunale Kooperation Stadt-Land-Schloss (Alsfeld, Antrifttal, Romrod)

Interkommunale Kooperationen: Interkommunale Kooperation Stadt-Land-Schloss (Alsfeld, Antrifttal, Romrod) - Alsfeld - Kernstadt - Antrifttal - Ruhlkirchen Romrod - Kernstadt; Bahnhof Romrod - Zell Kommunale Arbeitsgemeinschaft Hessisches Kegelspiel (Burghaun, Hünfeld, Nüsttal, Rasdorf) - Burghaun - Ortskern; Sport- Freizeitanlage Am Weiher Hünfeld - Bahnbereich; Innenstadt Hünfeld - Rasdorf - Ortskern; Sport- und Freizeitanlage Interkommunale Kooperation Hinterland - Bad Laaspe (Angelburg, Bad Endbach, Biedenkopf, Breidenbach, Dautphetal, Gladenbach, Lohra, Steffenberg) - Angelburg - Frechenhausen - Bad Endbach - Verbindung Bad Endbach – Hartenrod - Biedenkopf - Altstadt - Breidenbach - Ortsmitte - Dautphetal - Ortsmitte Dautphe - Gladenbach - Innenstadtinsel - Lohra - Ortsmitte - Steffenberg - Gewerbegebiet Niedereisenhausen Interkommunale Kooperation Bergstraße (Bensheim, Einhausen, Heppenheim, Lautertal (Odenwald), Lorsch, Zwingenberg) - Bensheim - Bensheim Südwest; Westliche Innenstadt - Einhausen - Ortszentrum - Heppenheim - An der Innenstadt Heppenheim - Lautertal - Felsenmeer Reichenbach; Ortsmitte Reichenbach in Lautertal - Lorsch - Stadt- und Kulturzentrum - Zwingenberg - Rund um die historische Markthalle Interkommunale Kooperation Schwalm-Eder-Mitte (Homberg (Efze), Knüllwald, Schwarzenborn) - Homberg (Efze) - Altstadt um den Marktplatz; Stadtteil Mühlhausen - Knüllwald - Remsfeld (in den Bereichen Stuhlfabrik, innerörtliche Siedlungsfläche mit dem entwidmeten Gebäude/ Grundstück der katholischen Kirche); Niederbeisheim (mit -

Martin Luther Extended Timeline Session 1

TIMELINES: MARTIN LUTHER & CHRISTIAN HISTORY A. LUTHER the MAN (1483 – 1546) 1502: Receives B.A. at University of Erfurt 1505: Earns M.A. at Erfurt; begins to study law 1505 Luther “struck by lightning” and vows to become a monk 1505 Luther enters the Order of Augustinian Hermits 1507: Luther is ordained and celebrates his first Mass; he panics during the ceremony 1510: Luther visits Rome as representative of Augustinians 1511: Luther transfers to Wittenberg to teach at the new university. 1512: Luther earns his doctorate of theology 1513: Luther begins lecturing on The Psalms 1515: Luther lectures on Paul’s Epistles to the Romans 1517: October 31, he posts his “95 Theses (points to debate)” concerning indulgences on Wittenberg Church door. 1518: At meeting in Augsburg, Luther defends his theology & refuses to recant 1518: Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony places Luther under his protection. 1519: In debates with Professor John Eck at Leipzig, Luther denies supreme authority of popes and councils 1520: Papal bull (Exsurge Domine) gives Luther 60 days to recant or be excommunicated 1520: Luther burns the papal bull and writes 3 seminal documents: “To the Christian Nobility,” “On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church,” & “The Freedom of a Christian” 1521: Luther is excommunicated by the papal bull Decet Romanum Pontificem 1521: He refuses to recant his writings at the Diet of Worms 1521: New HRE Charles V condemns Luther as heretic and outlaw Luther is “kidnapped” and hidden in Wartburg Castle Luther begins translating the New Testament -

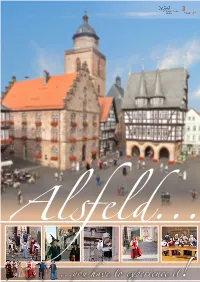

You Have to Experience

Alsfeld... ...you have to experience it! Bücking House on the Market Place (1893) Market Place with Wine House and Town Hall (1878) South side of the Market Place (approx.. 1870) If walls and arches could speak, they would tell the visitor many tales about the history of Alsfeld… Originally called “Adelesfelt”, Alsfeld was founded in 8th - 9th century as the seat of the Carolingian Court. It was first documented in 1069. In 1605, the Chronicles of “Hessica von Dillich” describe Alsfeld as a distinguished place and as the capital city of Hesse. This was due to the favourable geographical position on the trade routes leading from Frankfurt to Thuringia, thus cementing Alsfeld’s importance. Alsfeld had its own royal mint, market privileges and in 1222 acquired city status. 2 HistoricalA living reflection of history Tradition welcomes the future 3 European model city for heritage building Attractionsconservation. The famous Market Place Trio of the Town Hall, The Wedding House, The Stumpf House The Walpurgis Church, the main parish the Wine House and No.2 Market Place and The Bücking House church of Alsfeld Welcome to a town where the wood timbered architecture is a feast for your eyes! In 1878 the town councillors wanted to have the Town Hall pulled down. Luckily their plans were stopped. Since then no such thoughts have been entertained. On the contrary: preserve, maintain and renovate has become the motto of Alsfeld. The results were so exemplary and convincing that in 1975, the European Council selected Alsfeld as a European Model Town. An exciting excursion back in time is to walk through the town with its over 400 half-timbered buildings, spanning 700 years of history. -

Reinhardshausen Frankenau Schmittlotheim Herzhausen

Montag - Freitag Verkehrsbeschränkungen S S S S F 1-35S 4S S F F F F S S F Anmerkungen i i i Frankenau-Louisendorf, Schulbushaltestelle 7.05 Frankenau-Ellershausen 7.09 b 590.1 Bad Wildungen, Treffpunkt ab 9.50 11.50 13.50 521 b 590.1 Bad Wild.-Reinhardshsn. Friedhof an 10.17 12.17 14.17 Bad Wildungen-Reinhardshsn., Friedhof - 10.20 12.20 14.20 Bad Wildungen-Albertshausen - 10.22 12.22 14.22 b Edertal-Gellershausen, Sportplatz - 10.28 12.28 14.28 0 Försterei - 10.29 12.29 14.29 Bad Wildungen-Frebershausen, Forsthaus - 10.32 12.32 14.32 Bad Wildungen-Frebershausen - 10.33 12.33 14.33 Frankenau-Allendorf 7.12 - - - Frankenau, Paulsmühle 7.15 - - - Frankenberger Straße 7.17 - - - Kellerwaldschule - 8.17 - - 13.19 14.35 - b 520 Frankenberg, Bahnhof ab 5.30 6.26 7.30 7.30 8.24 8.24 9.30 9.30 9.30 11.30 11.30 12.30 13.30 13.30 b 520 Frankenau, Kindergarten an 5.54 6.50 7.54 7.54 8.54 8.54 9.54 9.54 9.54 11.54 11.54 12.54 13.54 13.54 b 520 Bad Wildungen, Bahnhof ab 6.00 6.30 7.30 8.30 8.30 9.30 9.30 9.30 11.30 11.30 12.28 13.36 13.30 b 520 Frankenau, Kindergarten an 6.29 6.59 7.59 8.59 8.59 9.59 9.59 9.59 11.59 11.59 12.59 14.05 13.59 Kindergarten 6.30 7.18 8.18 38.40 9.15 9.15 10.15 10.40 310.40 12.40 312.40 13.20 14.36 14.40 b 520 Frankenau, Kindergarten ab 7.54 8.54 10.54 12.54 13.54 14.54 14.54 b 520 Bad Wildungen, Bahnhof an 8.24 9.24 11.24 13.24 14.24 15.34 15.24 b 520 Frankenau, Kindergarten ab 7.54 8.59 10.59 12.59 14.05 14.59 14.59 b 520 Frankenberg, Bahnhof an 8.22 9.21 11.21 13.21 14.33 15.21 15.21 Feriendorf 6.31 7.19 8.19 8.41 9.16 -

Defending Faith

Spätmittelalter, Humanismus, Reformation Studies in the Late Middle Ages, Humanism and the Reformation herausgegeben von Volker Leppin (Tübingen) in Verbindung mit Amy Nelson Burnett (Lincoln, NE), Berndt Hamm (Erlangen) Johannes Helmrath (Berlin), Matthias Pohlig (Münster) Eva Schlotheuber (Düsseldorf) 65 Timothy J. Wengert Defending Faith Lutheran Responses to Andreas Osiander’s Doctrine of Justification, 1551– 1559 Mohr Siebeck Timothy J. Wengert, born 1950; studied at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor), Luther Seminary (St. Paul, MN), Duke University; 1984 received Ph. D. in Religion; since 1989 professor of Church History at The Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia. ISBN 978-3-16-151798-3 ISSN 1865-2840 (Spätmittelalter, Humanismus, Reformation) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2012 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproduc- tions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Martin Fischer in Tübingen using Minion typeface, printed by Gulde- Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. Acknowledgements Thanks is due especially to Bernd Hamm for accepting this manuscript into the series, “Spätmittelalter, Humanismus und Reformation.” A special debt of grati- tude is also owed to Robert Kolb, my dear friend and colleague, whose advice and corrections to the manuscript have made every aspect of it better and also to my doctoral student and Flacius expert, Luka Ilic, for help in tracking down every last publication by Matthias Flacius. -

Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530

PALPABLE POLITICS AND EMBODIED PASSIONS: TERRACOTTA TABLEAU SCULPTURE IN ITALY, 1450-1530 by Betsy Bennett Purvis A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto ©Copyright by Betsy Bennett Purvis 2012 Palpable Politics and Embodied Passions: Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530 Doctorate of Philosophy 2012 Betsy Bennett Purvis Department of Art University of Toronto ABSTRACT Polychrome terracotta tableau sculpture is one of the most unique genres of 15th- century Italian Renaissance sculpture. In particular, Lamentation tableaux by Niccolò dell’Arca and Guido Mazzoni, with their intense sense of realism and expressive pathos, are among the most potent representatives of the Renaissance fascination with life-like imagery and its use as a powerful means of conveying psychologically and emotionally moving narratives. This dissertation examines the versatility of terracotta within the artistic economy of Italian Renaissance sculpture as well as its distinct mimetic qualities and expressive capacities. It casts new light on the historical conditions surrounding the development of the Lamentation tableau and repositions this particular genre of sculpture as a significant form of figurative sculpture, rather than simply an artifact of popular culture. In terms of historical context, this dissertation explores overlooked links between the theme of the Lamentation, the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, codes of chivalric honor and piety, and resurgent crusade rhetoric spurred by the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Reconnected to its religious and political history rooted in medieval forms of Sepulchre devotion, the terracotta Lamentation tableau emerges as a key monument that both ii reflected and directed the cultural and political tensions surrounding East-West relations in later 15th-century Italy. -

Allmbl-2018-01.Pdf

AllgemeinesMinisterialblatt DER BAYERISCHEN STAATSREGIERUNG DES BAYERISCHEN MINISTERPRÄSIDENTEN · DER BAYERISCHEN STAATSKANZLEI DES BAYERISCHEN STAATSMINISTERIUMS DES INNERN, FÜR BAU UND VERKEHR DES BAYERISCHEN STAATSMINISTERIUMS FÜR WIRTSCHAFT UND MEDIEN, ENERGIE UND TECHNOLOGIE DES BAYERISCHEN STAATSMINISTERIUMS FÜR UMWELT UND VERBRAUCHERSCHUTZ DES BAYERISCHEN STAATSMINISTERIUMS FÜR ERNÄHRUNG, LANDWIRTSCHAFT UND FORSTEN DES BAYERISCHEN STAATSMINISTERIUMS FÜR ARBEIT UND SOZIALES, FAMILIE UND INTEGRATION DES BAYERISCHEN STAATSMINISTERIUMS FÜR GESUNDHEIT UND PFLEGE Nr. 1 München, 31. Januar 2018 31. Jahrgang Inhaltsübersicht Datum Seite I. Veröffentlichungen, die in den Fortführungsnachweis des Allgemeinen Ministerialblatts aufgenommen werden Bayerisches Staatsministerium des Innern, für Bau und Verkehr 12 .12 .2017 2030 .13-I Dienstliche Beurteilung, Leistungsfeststellungen nach Art . 30 und 66 BayBesG in Verbindung mit Art . 62 LlbG für die Beamten und Beamtinnen der Bayerischen Polizei und des Bayerischen Landesamtes für Verfassungsschutz (Beurteilungsbekanntmachung Polizei und Verfassungsschutz – BUBek-Pol/VS) . 3 22 .12 .2017 2330-I Richtlinie für das Kommunalinvestitionsprogramm zur Verbesserung der Schulinfrastruktur fi nanzschwacher Kommunen in Bayern (Kommunalinvestitionsprogramm Schulinfrastruktur – KIP-S) . 18 28 .12 .2017 913-I Richtlinie zur Ermittlung der Vergütung für die statische und konstruktive Prüfung von Ingenieur- bauwerken für Verkehrsanlagen, RVP (Ausgabe 2016) . 21 Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Ernährung, Landwirtschaft -

A FRISIAN MODEL Henryk Sjaardema

THE INDIVIDUATED SOCIETY: A FRISIAN MODEL Henryk Sjaardema Preface It has long seemed to me that the dynamic of human activity is directly related to ecological variables within the society. It is the intimate rela- tionship of-the individual to the requirements of his society that not only channels human energies, but provides a framework for value orientations as well. It is as if society were a vast complex of machinery and man the kinetic force driving it. As machinery falls into social disuse, malfunction and inoperation, man must turn to new or alternative avenues or see his kinetic energy fall into disuse. When the crucial social machinery becomes patterned and routinized a surplus of human energy is made available. The stable society has a way of rechanneling these energies into other roles. Where these addi- tional roles are not present-where energy becomes constricted--social revolu- tions transpire. This study has been directed toward one socio-economic segment of Western man in which the role of the individual has been measured against the ecological requirements of the society. This pilot study is an attempt to probe variables which seem crucial to the rise of the individuated society. Introduction Purpose. To investigate the individuated basis for Frisian society. If the total society can be considered in its broadest sense, as a social configuration which transcends the normal limits of thinking built into political conceptions of the totalitarian state, my meaning will be made clear- er. This social configuration is one which places the requirements of the commun'ity on all levels above that of the commnity's individual constituents.