Collusion in the Turkish Banking Sector Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TÜRKİYE İŞ BANKASI A.Ş. U.S.$5,000,000,000 Global Medium

TÜRKİYE İŞ BANKASI A.Ş. U.S.$5,000,000,000 Global Medium Term Note Program Under this U.S.$5,000,000,000 Global Medium Term Note Program (the "Program"), Türkiye İş Bankası A.Ş., a Turkish banking institution organized as a public joint stock company registered with the Istanbul Trade Registry under number 431112 (the "Bank" or the "Issuer"), may from time to time issue notes (the "Notes") denominated in any currency agreed between the Issuer and the relevant Dealer (as defined below). Notes may be issued in bearer or registered form (respectively "Bearer Notes" and "Registered Notes"). The maximum aggregate nominal amount of all Notes from time to time outstanding under the Program will not exceed U.S.$5,000,000,000 (or its equivalent in other currencies calculated as described in the Program Agreement described herein), subject to increase as described herein. The Notes may be issued on a continuing basis to: (a) one or more of the Dealers specified under "Overview of the Group and the Program" and any additional Dealer appointed under the Program from time to time by the Issuer (each a "Dealer" and together the "Dealers"), which appointment may be for a specific issue or on an ongoing basis, and/or (b) one or more investors purchasing Notes directly from the Issuer. References in this Base Prospectus to the "relevant Dealer" shall, in the case of an issue of Notes being (or intended to be) subscribed by more than one Dealer, be to all Dealers agreeing to subscribe such Notes. An investment in Notes issued under the Program involves certain risks. -

Akbank ESG Presentation 2Q21

Our ESG World’s Best Bank in the Emerging Markets Journey EUROMONEY (2020) October 2021 ESG Strategy: Mitigate environmental footprint while increasing positive impact Sustainable Finance Ecosystems Management Responsible Products & Services ‣ ‣ Digitalization Impact Investing ‣ ‣ Financial Inclusion To be the leading bank that drives Turkey into the future People & Community Climate Change Future of Work ‣ ‣ Operational Emissions Diversity & Inclusion ‣ ‣ Portfolio Impact Community Investment ‣ ‣ Portfolio Exposure Integrated Governance Financial Performance 2 Actionable targets for positive impact SUSTAINABLE TL 200 bn TL 15 bn AuM ECOSYSTEMS Extend digital & innovative FINANCE Sustainable loan Sustainable MANAGEMENT products & services financing until investment funds Supporting a more Enhancing businesses sustainable economy 2030 2030 & financial health Increase sustainable financing Increase number of financially secured by the bank until 2030 empowered people PEOPLE & Improve the Increase Social CLIMATE Become a carbon- Decrease impact of effectiveness of Return on neutral bank loan portfolio on COMMUNITY investment on our CHANGE Investments for through eliminating climate change Empowering our people people community Mitigating operational operational emission & portfolio until 2030 and communities investments emissions until 2025 impact Enhance the effectiveness of Akbank Mitigate climate-related risks & impact volunteerism in community investments on portfolio 3 Sustainability Governance Committee Members: Executive Board Member, -

Investor Presentation

Investor Presentation TAS Bank Only Results 2006 YE March, 2007 1 History Established in April 1954 under the special law “Türkiye Vakıflar Bankasi Türk Anonim Ortaklığı Kanunu” to manage cash derived from revenues and expenditures of charitable organisations set up during the Ottoman Empire period, conducting banking activities with branch offices in Ankara, Istanbul and Izmir In 1957, made its first venture towards broadening its sevices by establishing Güneş Insurance Company Over the next 20 years continued to expand its geographic presence in Turkey reaching 206 branches by 1977 Since the early 1990s, Vakifbank has increased the scope of its retail banking and diversified its loan portfolio by including equipment financing, enterprise loans, auto loans, mortgage loans, and credit cards. In 2000, Vakifbank began offering internet banking services Vakifbank is now a full service commercial and retail bank headquartered in Ankara, providing retail, commercial and investment banking services through a network of 311 branches, 116 satellite branches and five mobile branches, covering 81 Turkish cities Internationally, Vakifbank has subsidiaries in Austria (which operates a branch in Frankfurt and a branch in Köln) and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus and two branches in New York and Bahrain. 2 Following successful IPO in November 2005, c. 25% of Vakifbank of is now listed Main Shareholders Ownership structure General Directorate of Foundations The GDF manages foundations owning 58.45% of the shares General in the Bank (43.0% in the form of Class A shares and 15.45% Free float Directorate in the form of Class B shares). The GDF was established in 25,18% of Foundations 1924 to administer and regulate existing and future Turkish 58,45% charitable foundations as a state entity directly reporting to the Prime Minister. -

Banks in Turkey 2018 Banks in Turkey 2018

JUNE 2019 BANKS IN TURKEY 2018 BANKS IN TURKEY 2018 Publication No : 332 June 2019 ,661 SULQWHG ,661 RQOLQH ,6%1 SULQWHG ,6%1 RQOLQH &RS\ULJKW7KH%DQNV$VVRFLDWLRQRI7XUNH\ 3XEOLFDWLRQ1DPH %DQNVLQ7XUNH\ 3XEOLFDWLRQ7\SH /RFDO3HULRGLFDO 3XEOLFDWLRQ3HULRG $QQXDO 3XEOLFDWLRQ'DWH -XQH 2ZQHURIWKH3XEOLFDWLRQ 7KH%DQNV$VVRFLDWLRQRI7XUNH\ 0DQDJLQJ'LUHFWRU 'U(NUHP.HVNLQ $GGUHVV 1LVSHWL\H&DG$NPHUNH]%%ORN.DW(WLOHUøVWDQEXO 3KRQH )D[ (PDLO WEE#WEERUJWU 85/ ZZZWEERUJWUHQKRPH 3ULQWHGLQ *00DWEDDFÕOÕNYH7LFDUHW$ù $GGUHVV <ÕO0DK0$66ø7&DGGH1R%D÷FÕODUøVWDQEXO 3KRQH SE[ )D[ $OO ULJKWV UHVHUYHG 1R SDUW RI WKLV UHSRUW PD\ EH UHSURGXFHG RU WUDQVPLWWHG LQ DQ\ IRUP RU E\ DQ\ PHDQV HOHFWURQLF SKRWRFRS\LQJ RU RWKHUZLVH ZLWKRXW WKH SULRU ZULWWHQ SHUPLVVLRQ RI WKH %DQNV $VVRFLDWLRQ RI 7XUNH\ :KLOVW HYHU\ HIIRUW KDV EHHQ PDGH WR HQVXUH WKDW WKH LQIRUPDWLRQ FRQWDLQHG LQ WKLV ERRN LV FRUUHFW WKH %DQNV $VVRFLDWLRQ RI 7XUNH\ GRHV QRW DVVXPH DQ\ UHVSRQVLELOLW\ IRU DQ\ HUURUV RU RPLVVLRQV RU IRU DQ\ FRQVHTXHQFHVUHVXOWLQJWKHUHIURP 7KLV ERRN LV SUHSDUHG IURP WKH \HDUHQG DXGLWHG DQG QRQFRQVROLGDWHG 7KH &RPPRQ 'DWD 6HW RI GHSRVLW EDQNV DQG GHYHORSPHQW DQG LQYHVWPHQW EDQNV WKDW DUH SUHSDUHG LQ DFFRUGDQFH ZLWK %56$ V UHODWHG &RPPXQLTXH RI )LQDQFLDO 6WDWHPHQWV DQG 5HODWHG ([SODQDWLRQ DQG )RRWQRWHV RI %DQNV 7KDW LV 'LVFORVHG WR WKH3XEOLF &HUWLILFDWH1R < &RQWHQWV 3DJH1R 3UHIDFH«««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««« Y 0DLQ(FRQRPLF,QGLFDWRUV««««««««««««««««««««« YL (FRQRPLF'HYHORSPHQWVDQG%DQNLQJ6\VWHP««««««««««««« , *OREDO(FRQRP\«««««««««««««««««««««««««««« , 7XUNLVK(FRQRP\«««««««««««««««« -

Integrated Annual Review 2020

INTEGRATED ANNUAL REVIEW 2020 'The Meaning We Attach Please scan the QR to access the online report. to Words...' INTEGRATED ANNUAL REVIEW 2020 Content available on the website to watch, listen and read. Texts are linked to related website when clicked. Texts are linked to related pages in the report when clicked. Number of words used in the section Reading time of the section 'The Meaning Number of pages of the section We Attach The most used word in the section to Words...' in the banking sector to date. With our SUSTAINABILITY initiatives, we truly live up to this concept; we shape sustainability with our Contents Foreword commitment to create a robust and successful business model for the future by sharing long-lasting values with our stakeholders. 'THE MEANING WE ATTACH TO WORDS...' We feel responsible, primarily, for the world we live in, for our Finance and banking are associated first and foremost with environment, our employees, our customers, and most of all, for numbers, figures and ratios. Performance and goals are expressed our own operations. We act with this sense of RESPONSIBILITY 3 Foreword 92 OUR 2020 MATERIAL ISSUE: COVID-19 in numbers; so are current position and status. Yes, the finance at all times. According to us, AGILITY, taking action swiftly, being 4 About the Report sector likes numbers, because things that are quantifiable have dynamic and effective in the digitalizing order that races against 2020 PERFORMANCE IN STRATEGIC PRIORITIES priority and talking about measurement means talking about time, leading innovation while empowering our employees, flexibility INTRODUCTION AND OUTLOOK numbers since those that are not measured cannot be improved. -

Fitch Downgrades 14 Turkish Banks; Outlook Negative

7/22/2019 [ Press Release ] Fitch Downgrades 14 Turkish Banks; Outlook Negative Fitch Downgrades 14 Turkish Banks; Outlook Negative Link to Fitch Ratings' Report(s): Fitch Downgrades 14 Turkish Banks; Outlook Negative Fitch Ratings-London-19 July 2019: Fitch Ratings has downgraded the support-driven Long-Term Foreign Currency Issuer Default Ratings (LTFC IDRs) of 12 foreign-owned Turkish banks and their subsidiaries, and two state-owned development banks, Turkiye Ihracat Kredi Bankasi A.S. (Turk Eximbank) and Turkiye Kalkinma Bankasi A.S. (TKYB). The agency has also downgraded the Long-Term Local Currency IDRs of 22 banks and their subsidiaries. The Outlooks on all banks' Long-Term IDRs are Negative. Viability Ratings (VRs) are not affected as a result of these rating actions. A full list of rating actions is available at www.fitchratings.com or via the link above. The rating actions follow the downgrade of Turkey's sovereign rating on 12 July 2019 (see "Fitch Downgrades Turkey to 'BB-'; Outlook Negative" at www.fitchratings.com). In Fitch's view, the dismissal of Turkey's central bank governor heightens doubts about the authorities' tolerance for a period of sustained below-trend growth and disinflation that Fitch considers consistent with a rebalancing and stabilisation of the economy, and highlights a deterioration in Turkey's institutional independence and economic policy coherence and credibility. The downgrades of the foreign-owned Turkish banks' LTFC IDRs to 'B+' from 'BB-' reflects increased risk of government intervention in the banking sector in case of a marked deterioration in Turkey's external finances. We continue to view the risk of intervention that would prevent banks from servicing their FC obligations to be slightly higher than that of a sovereign default, and this result in these ratings being capped one notch below the sovereign LTFC IDR. -

Citigroup Reports Second Quarter 2012 Earnings Per

For Immediate Release Citigroup Inc. (NYSE: C) July 16, 2012 CITIGROUP REPORTS SECOND QUARTER 2012 EARNINGS PER SHARE1 OF $0.95; $1.00 EXCLUDING THE IMPACT OF POSITIVE CVA/DVA2 AND A NET LOSS ON THE SALE OF A 10.1% STAKE IN AKBANK T.A.S.3 CITIGROUP NET INCOME OF $2.9 BILLION; $3.1 BILLION EXCLUDING CVA/DVA AND THE LOSS ON AKBANK CITIGROUP REVENUES OF $18.6 BILLION; $18.8 BILLION EXCLUDING $219 MILLION OF CVA/DVA AND THE $424 MILLION LOSS ON AKBANK BASEL I TIER 1 COMMON RATIO INCREASED TO 12.7% ESTIMATED BASEL III TIER 1 COMMON RATIO INCREASED TO 7.9%4 BOOK VALUE PER SHARE INCREASED TO $62.61 TANGIBLE BOOK VALUE PER SHARE5 INCREASED TO $51.81 LOAN LOSS RESERVE RELEASE OF $984 MILLION IN SECOND QUARTER, DOWN 50% FROM THE PRIOR YEAR PERIOD CITIGROUP QUARTER-END DEPOSITS OF $914 BILLION, 6% ABOVE PRIOR YEAR PERIOD CITICORP LOANS OF $527 BILLION GREW 10% VERSUS PRIOR YEAR PERIOD CITI HOLDINGS LOANS OF $128 BILLION DECLINED 24% VERSUS PRIOR YEAR PERIOD CITI HOLDINGS ASSETS OF $191 BILLION DECLINED 28% FROM PRIOR YEAR PERIOD – REPRESENT 10% OF TOTAL CITIGROUP ASSETS New York, July 16, 2012 – Citigroup Inc. today reported net income for the second quarter 2012 of $2.9 billion, or $0.95 per diluted share, on revenues of $18.6 billion. CVA/DVA was a positive $219 million in the second quarter, resulting from the widening of Citi’s credit spreads, compared to a positive $164 million in the prior year period. -

CTF Impact on EE and RE Private Sector Financing Via Local Financial Institutions in Turkey

CTF Impact on EE and RE Private Sector Financing via Local Financial Institutions in Turkey Adonai Herrera-Martínez Energy Efficiency and Climate Change (E2C2) European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) on behalf of the Turkey CTF MDB team: OUTLINE All data refers to end of Q3 of 2012 CTF IMPACT ON EE/RE INVESTMENTS IP Stage 1 IP Stage 1 IP Stage 1 Planned Expected Difference Achieved 3Q-2012 Planned vs. Expected (end of 2012) Total Investment 1,650 1,377 2,154 18% (million $) CTF Investment 200* 150 172 -14% (million $) Co-Finance (million $) 1,450 1,227 1,982 20% CTF Leverage 8.2 9.2 10.8 31% (invested $/CTF $) GHG Savings (million 3.2 2.3 4.0 25% tons of CO2-e/yr) (1.6% of Turkey’s in 2009) Total investment: 56% in Renewable Energy and 44% in Energy Efficiency + Transformational impact: quantitative (e.g. MidSEFF) and non-quantitative (e.g. increased environmental and social standards, awareness raising) * Including $28 million to be utilised by IFC for RE direct investments CTF IMPACT ON THE EE/RE INVESTMENTS › Project Investment Breakdown Project Investment Breakdown by Bank Project Investment Breakdown by Bank $900 $800 IFC Millions $78 milion EBRD 6% $700 YapiKreditLeasing $446 million Vakifbank 32% $600 $568 TSKB $500 TKB Is Bank $400 $71 $59 Garant Bank $300 FinansLeasing $137 Denizbank IBRD $200 $853 million $65 $285 Akbank $100 62% $113 $25 $52 $0 EBRD IBRD IFC CTF IMPACT ON THE EE/RE INVESTMENTS › Total Number of Projects Invested • EE Projects – 375 (87%) Number of Projects Grand EE RE Total • RE Projects – 55 -

Citigroup Reports Fourth Quarter 2013 Earnings Per Share of $0.85; $0.82 Excluding Cva/Dva1 and Impact of the Credicard Divestiture2

For Immediate Release Citigroup Inc. (NYSE: C) January 16, 2014 CITIGROUP REPORTS FOURTH QUARTER 2013 EARNINGS PER SHARE OF $0.85; $0.82 EXCLUDING CVA/DVA1 AND IMPACT OF THE CREDICARD DIVESTITURE2 FOURTH QUARTER NET INCOME OF $2.7 BILLION; $2.6 BILLION EXCLUDING CVA/DVA AND IMPACT OF THE CREDICARD DIVESTITURE FOURTH QUARTER REVENUES OF $17.8 BILLION; $17.9 BILLION EXCLUDING CVA/DVA FOURTH QUARTER NET CREDIT LOSSES OF $2.5 BILLION DECLINED 15% VERSUS PRIOR YEAR PERIOD UTILIZED APPROXIMATELY $600 MILLION OF DEFERRED TAX ASSETS ESTIMATED BASEL III TIER 1 COMMON RATIO OF 10.5%3 ESTIMATED BASEL III SUPPLEMENTARY LEVERAGE RATIO OF 5.4%4 BOOK VALUE PER SHARE INCREASED TO $65.31 TANGIBLE BOOK VALUE PER SHARE5 INCREASED TO $55.38 CITIGROUP DEPOSITS OF $968 BILLION GREW 4% VERSUS PRIOR YEAR PERIOD CITICORP LOANS OF $575 BILLION GREW 7% VERSUS PRIOR YEAR PERIOD CITI HOLDINGS ASSETS OF $117 BILLION DECLINED 25% FROM PRIOR YEAR PERIOD AND REPRESENTED 6% OF TOTAL CITIGROUP ASSETS AT YEAR END 2013 New York, January 16, 2014 – Citigroup Inc. today reported net income for the fourth quarter 2013 of $2.7 billion, or $0.85 per diluted share, on revenues of $17.8 billion. This compared to net income of $1.2 billion, or $0.38 per diluted share, on revenues of $17.9 billion for the fourth quarter 2012. CVA/DVA was a negative $164 million ($100 million after-tax) in the fourth quarter, mainly resulting from the improvement in Citigroup’s credit spreads, compared to negative $485 million ($301 million after-tax) in the prior year period. -

Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Ziraat Bankasi A.Ş

BASE PROSPECTUS TÜRKİYE CUMHURİYETİ ZİRAAT BANKASI A.Ş. U.S.$4,000,000,000 Global Medium Term Note Programme Under this U.S.$4,000,000,000 Global Medium Term Note Programme (the "Programme"), Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Ziraat Bankası A.Ş., a banking institution organised as a joint stock company under the laws of Turkey and registered with the Ankara Trade Registry under number 1148 (the "Bank" or the "Issuer"), may from time to time issue notes (the "Notes") denominated in any currency agreed between the Issuer and the relevant Dealer (as defined below). Notes may be issued in bearer or registered form (respectively "Bearer Notes" and "Registered Notes"). The maximum aggregate nominal amount of all Notes from time to time outstanding under the Programme will not exceed U.S.$4,000,000,000 (or its equivalent in other currencies calculated as described in the Programme Agreement described herein), subject to increase as described herein. The Notes may be issued on a continuing basis to: (a) one or more of the Dealers specified under "Overview of the Bank and the Programme" and any additional Dealer appointed under the Programme from time to time by the Issuer (each a "Dealer" and together the "Dealers"), which appointment may be for a specific issue or on an ongoing basis, and/or (b) one or more investors purchasing Notes directly from the Issuer. References in this Base Prospectus ("Base Prospectus") to the "relevant Dealer" shall, in the case of an issue of Notes being (or intended to be) subscribed by more than one Dealer, be to all Dealers agreeing to subscribe such Notes. -

Banking Track

BANKING TRACK Organized by the BankingTechnology Club during the Economic Mission led by HRH Prince Philippe to Turkey 15-17 October 2012 In cooperation with 1. CONTACT PERSONS Agoria BankingTechnology Club Agoria International Business Debbie Thys Peter Demuynck +32.494.46.43.30 +32.477.52.72.82 [email protected] [email protected] More information: www.bankingtechnologyclub.be 2. PROGRAM TUESDAY 16 OCTOBER - ISTANBUL 10.00 Visit to Ziraat Bankasi - http://www.ziraat.com.tr Meeting with the Payment Systems Group President Ziraat bank is the second largest Bank in Turkey, after Is Bank. The bank has a strong focus on servicing its customers, having the largest service network in Turkey including ATM’s, Call Centers, Online Banking, Mobile Banking, etc. Ziraat Bank has a strategy to grow not only domestically, but also to enlarge its global footprint. Today Ziraat Bank has 76 service points in 16 countries. 12.00 Power Lunch ‘Banking’ in the Presence of HRH Prince Philippe from Belgium at the Residence of the Consul General in Istanbul Power lunch to promote the know how of Belgian IT companies, all suppliers for the financial industry, towards the decision makers of the Turkish Banks. Keynote from Minister Benoît CereXhe, followed by an introduction of the members of the Banking Technology Club. For more info on the Turkish participants, see addendum 1. Economic Mission led by HRH Prince Philippe to Turkey - Banking Track ______________________________________________ 1 15u00 Visit to Is Bankasi – http://www.isbank.com .tr Meeting with the Division Head Information Technologies Is Bankasi is Turkey’s first public bank and premier national financial institution. -

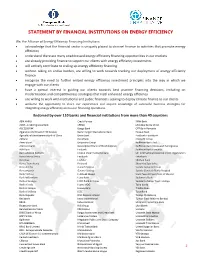

Statement by Financial Institutions on Energy Efficiency

STATEMENT BY FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS ON ENERGY EFFICIENCY We, the Alliance of Energy Efficiency Financing Institutions: acknowledge that the financial sector is uniquely placed to channel finance to activities that promote energy efficiency understand there are many unaddressed energy efficiency financing opportunities in our markets are already providing finance to support our clients with energy efficiency investments will actively contribute to scaling up energy efficiency financing without taking on undue burden, are willing to work towards tracking our deployment of energy efficiency finance recognise the need to further embed energy efficiency investment principles into the way in which we engage with our clients have a special interest in guiding our clients towards best practice financing decisions, including on modernisation and competitiveness strategies that instil enhanced energy efficiency are willing to work with institutional and public financiers seeking to deploy climate finance to our clients welcome the opportunity to share our experiences and acquire knowledge of successful business strategies for integrating energy efficiency across our financing operations. Endorsed by over 110 banks and financial institutions from more than 40 countries ABN AMRO Credit Foncier NRW Bank ACBA - Credit Agricole Bank CREDO Ohridska Banka Ohrid ACCESSBANK Daegu Bank OTP Bank Romania Agjencioni Per Financim NE Kosove Demir Kyrgyz International Bank Pireaus Bank Agricultural Development Bank of China Demirbank Postbank—Eurobank