Il Mantovano Hebreo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EARLY MUSIC NOW with SARA SCHNEIDER Broadcast Schedule — Summer 2020

EARLY MUSIC NOW WITH SARA SCHNEIDER Broadcast Schedule — Summer 2020 PROGRAM #: EMN 20-01 RELEASE: June 22, 2020 Treasures from Wolfenbüttel Starting in the late Renaissance, the court at Wolfenbüttel in northern Germany emerged as a cultural center. The dukes of the house of Welf employed high-profile composers like Michael Praetorius to increase their prestige, but lesser masters like Daniel Selichius made their mark as well. In this edition of Early Music Now, we'll hear from both composers, with performances by the Huelgas Ensemble and Weser-Renaissance Bremen. PROGRAM #: EMN 20-02 RELEASE: June 29, 2020 Those Talented Purcells This week's show focuses on Henry Purcell, and his lesser-known brother (or cousin) Daniel. We'll hear chamber music by both composers, plus selections from the semiopera they worked on together: The Indian Queen, from a 2015 release by The Sixteen. PROGRAM #: EMN 20-03 RELEASE: July 6, 2020 The Lost Voices of Hagia Sophia This week's program showcases an extraordinary recent release from the Portland-based ensemble Cappella Romana. This recording of medieval Byzantine chant composed for Hagia Sophia was recorded entirely in live, virtual acoustics, and soared to #1 on Billboard's Traditional Classical chart! These evocative sounds linger in the soul long after the music fades. PROGRAM #: EMN 20-04 RELEASE: July 13, 2020 Salomone Rossi: Revolutionary Jewish composer Salomone Rossi was a musician who served the Gonzaga court in Mantua. They valued him so highly that he was given a relatively large amount of personal freedom, while other members of the Jewish faith were restricted. -

Early Music Review EDITIONS of MUSIC Here Are Thirteen Works in the Present Volume

Early Music Review EDITIONS OF MUSIC here are thirteen works in the present volume. The first two are masses by John Bedingham, while the others are anonymous mass movements (either New from Stainer & Bell T single or somehow related). Previous titles in the series have been reviewed by Clifford Bartlett, and I confess this English Thirteenth-century Polyphony is the first time I have looked at repertory from this period A Facsimile Edition by William J. Summers & Peter M. since I studied Du Fay at university! At that time I also Lefferts sang quite a lot of (slightly later) English music, so I am not Stainer & Bell, 2016. Early English Church Music, 57 completely unfamiliar with it. I was immediately struck 53pp+349 plates. by the rhythmic complexity and delighted to see that the ISMN 979 0 2202 2405 8; ISBN 978 0 85249 940 5 editions preserve the original note values and avoids bar £180 lines - one might expect this to complicate matters with ligatures and coloration to contend with, but actually it is his extraordinarily opulent volume (approx. 12 laid out in such a beautiful way that everything miraculously inches by 17 and weighing more than seven pounds makes perfect sense. Most of the pieces are in two or three T- apologies for the old school measurements!) is a parts (a fourth part – called “Tenor bassus” – is added to marvel to behold. The publisher has had to use glossy paper the Credo of Bedingham’s Mass Dueil angoisseux in only in order to give the best possible colour reproductions of one of the sources). -

Programmbuch Festtage Alte Musik Basel

Basel, 23. bis 31. August 2013 Programmbuch Festtage Alte Musik Basel Wege zum Barock – Tradition und Avantgarde um 1600 www.festtage-basel.ch Titel: Pieter Lastman (1583–1633), David im Tempel, 1618, signiert und datiert, Holz, 1 79 cm x 117 cm, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Braunschweig Zum Geleit Mit der grössten Freude stelle ich der zweiten Edition der Festtage Alte Musik Basel diesen Gruss voran! Die Freude betrifft zuerst die Tatsache, dass die «Kulturstadt Basel» mit sol- chen Ereignissen eine «Fes- tivalstadt» par excellence ist, in der ein hervorragen- des Potenzial an Kreativität herrscht. Grund zur Freu- de ist auch die Bereiche- rung des grossen Gebiets Abdruck mit Quellenangabe erwünscht der Alten Musik, die seit © 2013 Paul Sachers Zeiten einen Verein zur Förderung Basler Absolventen Schwerpunkt des hiesigen auf dem Gebiet der Alten Musik Musiklebens darstellt. Aber Dornacherstrasse 161 A, CH-4053 Basel auch das Auftreten vieler Telefon +41 (0)61 361 03 54 berühmter europäischer En- CH17 0840 1016 1968 0160 3 sembles in Basel, die ohne dieses Festival hier nicht [email protected] zu hören wären, ist sehr lo- www.festtage-basel.ch benswert. Besonders erfreu- Redaktion: Jörg Fiedler, Peter Reidemeister lich ist aber das klare Profil Satz, Gestaltung: Buser, Kommunikation GmbH, Basel des Programms, das höchste Dr. Guy Morin, Regierungspräsident Druck: Druckerei Dietrich AG, Basel Qualität mit der Förderung des Kantons Basel-Stadt des Basler Nachwuchses verbindet: Wer in dieser Stadt Festtage Basel seine Ausbildung durchlaufen und diesem hohen Stan- Geschäftsleitung: Renato D. Pessi Künstlerische Leitung: Peter Reidemeister dard standgehalten hat, der hat es auch verdient, dass er hier mit Engagements zu solchen Ereignissen wei- Preis: 10 Franken terhin Unterstützung erfährt. -

ADORATIO.-Over-Heiligen-Martelaren-En-Geliefden.Pdf

Inhoudstafel Voorwoord | Philip Heylen 9 Laus Polyphoniae 2017 | dag aan dag 13 Introductie | Bart Demuyt 23 Essays Verering van de maagd Maria en het Kind in muziek uit de middeleeuwen en de renaissance | David J. Rothenberg 29 Romance met de roos: de minnekunst in het middeleeuwse en renaissancelied | Jane Alden 125 Een andere Petrarca: Italiaanse renaissancemuziek en Petrarca’s poëzie | Marc Vanscheeuwijck 195 Trahe me post te: muziek, gemeenschap en devotie in het vroegmoderne katholicisme | Daniele V. Filippi 305 Concerten VR 18/08/17 20.00 Stile Antico 41 ZA 19/08/17 10.00 IYAP-concertwandeling 53 11.00 Alexandra Aerts, Lieselot De Wilde & Sofie Vanden Eynde 83 16.00 Alexandra Aerts, Lieselot De Wilde & Sofie Vanden Eynde 83 20.00 Patrizia Bovi, Fadia Tomb El-Hage & Friends 85 22.15 Huelgas Ensemble 101 ZO 20/08/17 10.00 IYAP-concertwandeling 53 11.00 Alexandra Aerts, Lieselot De Wilde & Sofie Vanden Eynde 83 16.00 Alexandra Aerts, Lieselot De Wilde & Sofie Vanden Eynde 83 20.00 Cappella Pratensis, Flanders Boys Choir & Wim Diepenhorst 115 4 5 MA 21/08/17 13.00 Ensemble Leones 141 Radio-uitzending, cursussen, lezingen 20.00 Mala Punica 151 KlaraLive@LausPolyphoniae 27 22.15 Stile Antico 149 Ad tempo taci | filmdocumentaire met Marco Beasley 175 Petrarca & music | lezing door Marc Van Scheeuwijck 217 DI 22/08/17 13.00 VivaBiancaLuna Biffi & Pierre Hamon 165 Mariadevotie en heiligenverering in de late middeleeuwen | cursus 253 20.00 Vox Luminis 179 Isola Idola | muziekvakantie voor kinderen & jongeren 303 22.15 Zefiro Torna & Frank -

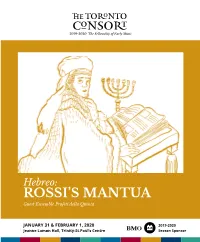

Hebreo: Rossi's Mantua House Program

2019-2020: The Fellowship of Early Music Hebreo: ROSSI’S MANTUA Guest Ensemble Profeti della Quinta JANUARY 31 & FEBRUARY 1, 2020 2019-2020 Jeanne Lamon Hall, Trinity-St.Paul’s Centre Season Sponsor THANK YOU! This production is made possible by The David Fallis Fund for Culture Bridging Programming It is with sincere appreciation and gratitude that we salute the following supporters of this fund: Anonymous (2) Matthew & Phyllis Airhart Michelle & Robert Knight Rita-Anne Piquet The Pluralism Fund Join us at our Intermission Café! The Toronto Consort is happy to offer a wide range of refreshments: BEVERAGES SNACKS PREMIUM ($2) ($2) BAKED GOODS ($2.50) Coffee Assortment of Chips Assortment by Tea Assortment of Candy Bars Harbord Bakery Coke Breathsavers Diet Coke Halls San Pellegrino Apple Juice Pre-order in the lobby! Back by popular demand, pre-order your refreshments in the lobby and skip the line at intermission! PROGRAM The Songs of Salomon HaShirim asher liShlomo Music by Salomone Rossi and Elam Rotem Salomone Rossi Lamnatséah ‘al hagitít Psalm 8 (c.1570-1630) Elohím hashivénu Psalm 80:4, 8, 20 Elam Rotem Kol dodí hineh-zéh bá Song of Songs 2: 8-13 Siméni chachotám al libécha Song of Songs 8: 6-7 Girolamo Kapsperger Passacaglia (ca. 1580-1651) Salomone Rossi Shir hama’alót, ashréy kol yeré Adonái Psalm 128 Hashkivénu Evening prayer Elam Rotem Shechoráh aní venaváh Song of Songs 1: 5-7 Aní yeshenáh velibí er Song of Songs 5:2-16, 6:1-3 INTERMISSION – Join us for the Intermission Café, located in the gym. -

Profeti Della Quinta

Profeti della Quinta „Renaissancemusik zum Verlieben!“ titelten die Potsdamer Neueste Nachrichten und bestätigten damit, dass man mit dem Repertoire des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts begeistern kann. Das Vokalensemble Profeti della Quinta hat sich eben dieser Musik verschrieben und sein Ausgangspunkt ist das fundierte Musizieren nach der Aufführungspraxis der jeweiligen Zeit, gepaart mit dem Bewusstsein für das heutige Publikum und dessen Hörgewohnheiten. Das Ensemble wurde in Galiläa in Israel von Elam Rotem, Bassist und Cembalist, gegründet. Mittlerweile ist es in der Schweiz ansässig, wo alle seine Mitglieder weiterführende Studien an der Schola Cantorum Basiliensis absolvierten. Wie der Name schon sagt, besteht das Ensemble im Kern aus fünf Sängern, die nach Bedarf mit befreundeten InstrumentalistInnen und SängerInnen aus der Schweiz, Japan und Australien zusammenarbeiten. Erste Bekanntheit erlangten die „Profeti“ durch Emilio de Cavalieris Lamentationen (1600) sowie Salomone Rossis Hashirim asher li’Shlomo (1623), der ersten Veröffentlichung hebräischer, polyphoner Musik. Mit der CD-Einspielung dieses Werks und eines Dokumentarfilms über Salomone Rossi, gefilmt an den Originalorten in Mantua, wurde dann auch die internationale Presse auf das schweizerisch-israelische Ensemble aufmerksam. Und zusammen mit dem Preis des York Early Music Young Artists Competition (2011) kamen dann die ersten wichtigen Einladungen aus Europa, Nordamerika, Israel, China und Japan. Zu den wichtigsten internationalen Festivals und Reihen gehören u.a. das Oude Muziek Festival Utrecht, das Rheingau Musik Festival, die Musikfestspiele Potsdam, die Beethovenfest Bonn, das London Festival of Baroque Music, die Einladung in das Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York oder in die Shanghai Concert Hall. 2019 begeisterte Profeti della Quinta gemeinsam mit etwa 15 Gästen unter der musikalischen Leitung von Elam Rotem das Publikum der Trigonale im österreichischen St. -

Jacobson 2020

Editing Rossi Preparing the synagogue music of Salamone Rossi —published in 1622— for modern performers -Joshua R. Jacobson 2020 Editing Rossi Joshua Jacobson page 2 In 1622 Bragadini Publishers in Venice issued a collection of polyphonic motets the likes of which had never been seen before. This was an anthology of motets not for the church, but for the synagogue, with lyrics not in Latin but in Hebrew. Composed by the Mantuan Jew Salamone Rossi, this unique collection was destined to remain the only one of its kind for several centuries. We don’t know much about Salamone Rossi. He was born circa 1570. His first published music is a book of nineteen canzonets printed in 1589.1 His last published music is dated 1628, a book of two-part madrigaletti. And after that there is nothing. Perhaps he died in the plague of 1628. Perhaps he died during the Austrian invasion in 1630. We just don’t know. His published output consists of six books of madrigals, one book of canzonets, one balletto from an opera, one book of madrigaletti, four books of instrumental works (sonatas, sinfonias, and various dance pieces), and the path-breaking collection of synagogue motets: in all, some 313 compositions published between 1589 and 1628. Rossi also composed music for a renowned Jewish theatre ensemble, but, alas, none of it was published, none has survived.2 Rossi was employed at the ducal palace in Mantua, where he served as a violinist and composer. He was quite the avant garde composer. His trio sonatas are among the first to appear in print.3 Rossi’s -

AEC Early Music Platform 2017 at the Royal Conservatoire the Hague

AEC Early Music Platform 2017 at the Royal Conservatoire The Hague 23rd – 24th March 2017 Curious about Curricula? Early Music study programmes today and tomorrow 1 The AEC would like to express deep gratitude to the Royal Conservatoire The Hague for hosting and co-organising the EMP Meeting 2017. The AEC team would also like to express special thanks to the members of the EMP preparatory working group, EUBO and REMA for their tremendous support in organising the platform programme. 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION: Curious about Curricula? Early Music study programmes today and tomorrow ............................................................................................................................................................ 5 PROGRAMME ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 THURSDAY 23rd MARCH .......................................................................................................................... 6 FRIDAY 24th MARCH ................................................................................................................................. 8 KC Concert Programme - Friday 24th March,17:45 Oude Katholieke Kerk .................. 9 Pascal Bertin, Counter-tenor ....................................................................................................... 10 ABSTRACTS of the SESSIONS and SPEAKERS’ BIOGRAPHIES .................................................... 11 Plenary Keynote -

The Monteverdi Festival Programme

THE MONTEVERDI FESTIVAL PROGRAMME Saturday 5th May, 9.00 pm – Chiesa S. Marcellino GLORIA E IMENEO Musiche di A. Vivaldi EUROPA GALANTE Sonia Prina, mezzosoprano Vivica Genaux, mezzosoprano Fabio Biondi, direzione Commissioned in 1725 by the French Ambassador in Venice to commemorate the nuptials of Louis XV and the Polish princess Maria Leszczynska, the serenata Gloria e Imeneo contains some of Vivaldi’s finest music, alternating virtuosity with elegance, poignancy, and dramatic fervour. Hymen and Glory compete each other in celebrating the radiant future of the French monarchy, and in congratulating the young royal couple in the most extravagant style, to join in a grand finale. The inaugurating battle of the Festival will be fought by two ravishing Baroque heroines, Sonia Prina and Vivica Genaux, accompanied by Fabio Biondi’s exciting Europa Galante. Sunday 6th May, 6.00 pm – Auditorium Giovanni Arvedi (Museo del Violino) PROLOGUE Prologhi e Sinfonie di G. Caccini, F. Cavalli, A. Cesti, C. Monteverdi, A. Stradella IL POMO D’ORO Francesca Aspromonte, soprano Enrico Onofri, violino e direzione Eurydice, Dido, Venus, the Austrian Glory, the Peace, Art of Painting, Music…. Nymphs, queens, gods and allegorical characters used to introduce the audience to 17th century operas; themes and feeling were quickly set, anticipating the meaning of the plot they would soon learn. A selection of the most beautiful prologues and symphonies by Cavalli, Cesti, Monteverdi and Stradella are embodied here by rising star Francesca Aspromonte and the fresh and dynamic ensemble Il Pomo d’Oro lead by Enrico Onofri. Tuesday 8th May, 9.00 p.m. – Palcoscenico del Teatro Ponchielli MADRIGALI, MOTTETTI, CANZONI DA SONAR Musica strumentale a Venezia tra Cinque e Seicento di G.Gabrieli, L. -

Wege Zum Barock – Tradition Und Avantgarde Um 1600 Freitag, 23

Festtage Alte Musik Basel, 23. bis 31. August 2013 Wege zum Barock – Tradition und Avantgarde um 1600 Freitag, 23. August 2013 20.15 Uhr Eröffnungskonzert Martinskirche Il Concerto sacro – Doppelchörigkeit alla Milanese e alla Veneziana Eintritt: 50/40/30 CHF nummerierte Plätze Concerto Palatino, Bruce Dickey, Charles Toet Samstag, 24. August 2013 12.15 Uhr Alumni 1, Mittagskonzert Klingental «Concerto delle dame» – Solomadrigale für 1, 2 und 3 Soprane, Eintritt frei, Kollekte Werke von Luzzasco Luzzaschi, Claudio Monteverdi, Girolamo Frescobaldi u.a. Ensemble Il Zabaione Musicale 18 Uhr Vortrag 1 Kunstmuseum, Vortragssaal Fünf Stimmen für das Ich? Wie das Individuum Eingang in den Tonsatz fand Eintritt frei Prof. Dr. Silke Leopold 20.15 Uhr Il Ballo del Granduca – Vom Renaissance- zum Barocktanz Martinskirche Tanz und Tanzmusik aus Italien und Frankreich von Malvezzi bis Lully Eintritt: 50/40/30 CHF nummerierte Plätze Tanzduo Il Ballarino Ensemble Musica Fiorita, Daniela Dolci Sonntag, 25. August 2013 10 Uhr Musik im Gottesdienst, mit Abendmahl Münster zu Basel Cypriano de Rore, Missa «Doulce memoire» Eintritt frei, Kollekte Brabant Ensemble, Oxford Stephen Rice 15 Uhr und 17 Uhr Stadtführung mit Mitarbeitern der kantonalen Denkmalpflege Basel-Stadt Besammlungsort Dr. Thomas Lutz, Dr. Martin Möhle Innenhof des Rathauses Eintritt frei 19 Uhr Benefizveranstaltung zugunsten des Vereins zur Förderung von Basler Absolventen auf dem Gebiet der Alten Musik Schützenhaus Nuove Musiche – Italienische und spanische Musik um 1600 300 CHF Ensemble Diminuito, Rolf Lislevand Festessen nach historischen Rezepten Montag, 26. August 2013 18 Uhr Vortrag 2 Kunstmuseum, Vortragssaal Sozusagen ein Instrument der Götter – Die Lyra und ihre Metamorphosen Eintritt frei Dr. -

Almanach Der Tage Alter Musik Regensburg 2015

ALMANACH 22. BIS 25. MAI 2015 MUSIK VOM MITTELALTER BIS ZUR ROMANTIK KONZERTE AN HISTORISCHEN STÄTTEN 2015 PRO MUSICA ANTIQUA präsentiert Freitag, 13. Mai 2016, 20.00 Uhr Sonntag, 15. Mai 2016, 22.45 Uhr Dreieinigkeitskirche Dominikanerkirche REGENSBURGER DOMSPATZEN CUT CIRCLE (USA) & L’ORFEO BAROCKORCHESTER Leitung: (Österreich) Jesse Rodin Leitung: Roland Büchner My Fair Lady – Joseph Haydn – Missa in tempo- Guillaume Du Fay – re belli C-Dur „Paukenmesse“ – Missa Ecce ancilla Salve Regina g-Moll – Sinfonie Domini/ Beata es Nr. 30 C-Dur „Alleluja“ Maria & Marienmo- tetten von Josquin, Freitag, 13. Mai 2016, 22.45 Uhr Busnoys, Ockeghem Schottenkirche St. Jakob 13. - 16. MAI 2016 Montag, 16. Mai 2016, 11.00 Uhr TIBURTINA ENSEMBLE (Tschechien) Musik vom Mittelalter bis zur Romantik – Thon Dittmer Palais (bzw. Reichssaal) Leitung: Konzerte an historischen Stätten Barbora Kabátková ZEFIRO (Italien) Regina Lucti – Samstag, 14. Mai 2016, 22.45 Uhr Leitung & Königin der Trauer – Minoritenkirche Oboe: Alfredo Gesang & Poesie Bernardini LA COMPAGNIA DEL am Hofe Wenzes- Harmoniemusik MADRIGALE (Italien) laus II. um 1300 & Türkenmode – Carlo Gesualdo da Bläsermusik für Venosa – Ausge- Samstag, 14. Mai 2016, 11.00 Uhr Hof, Kirche und wählte Madrigale Reichssaal Militär um aus den sechs Ma- 1800 LA RITIRATA (Spanien) drigalbüchern Il spiritillo brando – Montag, 16. Mai 2016, 14.00 Uhr Tänze am Hof der Sonntag, 15. Mai 2016, 11.00 Uhr Minoritenkirche spanischen Vize- Reichssaal könige in Neapel CLUB MEDIÉVAL L’ACHÉRON (17. Jh.) (Belgien) (Luxemburg) Leitung: Leitung: Thomas Baeté Anthony Holborne – Josetxu Obregón „Amor, tu solo’l sai“ – The Fruit of Love – Ballate, Madrigale & Englische Tanzmusik für Samstag, 14. Mai 2016, 14.00 Uhr Instrumentalmusik Gambenconsort Neuhaussaal von Paolo da Firenze Leitung & Viola da gamba: (1355-1436) ENSEMBLE SINN & TON (Deutschland) François Joubert-Caillet „Der Sturm“ nach Montag, 16. -

Profeti Della Quinta

Profeti della Quinta Philippe Verdelot: vierstimmige Madrigale BR Klassik, 25. April 2021 // Thorsten Preuß Eine Stunde Verdelot-Madrigale – das verspricht brave Gleichförmigkeit, gediegene Öde. Dachte ich. Bis ich die CD dann doch einlegte – und mich verliebte. (…) Gleich zu Beginn ein Wohlfühl-Bad zum Hineinlegen: Was für ein fülliger, homogener Klang, warm, weich und ausgewogen. Was für eine einfache, aber wirkungsvolle Harmonik. (…) Durchhörbar ist der Klang, glasklar die Artikulation, der Text so deutlich gesungen, als wäre er gesprochen. Und so fallen auch die ersten zaghaften Versuche von Tonmalerei auf, die Verdelot wagt: wenn er zum Beispiel mit raschen Notenwerten den Wind imitiert. Keine Frage: die Profeti della Quinta haben das Beste aus der Corona-Situation gemacht – für sich, für uns, für Verdelot. erika esslinger konzertagentur, Werfmershalde 13, 70190 Stuttgart Fon +49 (0)711 722 3440, Fax: +49 (0)711 722 34411, [email protected], www.konzertagentur.de Profeti della Quinta Monteverdis "L'Orfeo" Glasklarer Gesang bei der Trigonale in St. Veit/Glan Opera Online, 27. Oktober 2019 // Dr. Helmut Christian Mayer (...) großartigen Musik von Claudio Monteverdi (...) Und diese ist bei Elam Rotem, der vom Cembalo, Orgel oder Regal aus seine rund 20 musikalischen Mitstreiter leitet und zudem noch beim Chor mitsingt, in besten Händen: Denn frisch, stilsicher und nuancenreich wird die Partitur von den engagierten Musikern, die alle in grünen T-Shirts mit der Aufschrift „Orpheus and the Lyres“ stecken, wiedergegeben. Und hierbei passiert das Wichtigste: Es gelingt ihnen, das Publikum damit sehr zu berühren. (...) Das Publikum im ausverkauften Innenhof zeigt sich restlos begeistert und spendet stehende Ovationen! erika esslinger konzertagentur, Werfmershalde 13, 70190 Stuttgart Fon +49 (0)711 722 3440, Fax: +49 (0)711 722 34411, [email protected], www.konzertagentur.de Profeti della Quinta Sinnlichkeit in Klang und Wort Die Oberbadische, 17.