Jacobson 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EARLY MUSIC NOW with SARA SCHNEIDER Broadcast Schedule — Summer 2020

EARLY MUSIC NOW WITH SARA SCHNEIDER Broadcast Schedule — Summer 2020 PROGRAM #: EMN 20-01 RELEASE: June 22, 2020 Treasures from Wolfenbüttel Starting in the late Renaissance, the court at Wolfenbüttel in northern Germany emerged as a cultural center. The dukes of the house of Welf employed high-profile composers like Michael Praetorius to increase their prestige, but lesser masters like Daniel Selichius made their mark as well. In this edition of Early Music Now, we'll hear from both composers, with performances by the Huelgas Ensemble and Weser-Renaissance Bremen. PROGRAM #: EMN 20-02 RELEASE: June 29, 2020 Those Talented Purcells This week's show focuses on Henry Purcell, and his lesser-known brother (or cousin) Daniel. We'll hear chamber music by both composers, plus selections from the semiopera they worked on together: The Indian Queen, from a 2015 release by The Sixteen. PROGRAM #: EMN 20-03 RELEASE: July 6, 2020 The Lost Voices of Hagia Sophia This week's program showcases an extraordinary recent release from the Portland-based ensemble Cappella Romana. This recording of medieval Byzantine chant composed for Hagia Sophia was recorded entirely in live, virtual acoustics, and soared to #1 on Billboard's Traditional Classical chart! These evocative sounds linger in the soul long after the music fades. PROGRAM #: EMN 20-04 RELEASE: July 13, 2020 Salomone Rossi: Revolutionary Jewish composer Salomone Rossi was a musician who served the Gonzaga court in Mantua. They valued him so highly that he was given a relatively large amount of personal freedom, while other members of the Jewish faith were restricted. -

Early Music Review EDITIONS of MUSIC Here Are Thirteen Works in the Present Volume

Early Music Review EDITIONS OF MUSIC here are thirteen works in the present volume. The first two are masses by John Bedingham, while the others are anonymous mass movements (either New from Stainer & Bell T single or somehow related). Previous titles in the series have been reviewed by Clifford Bartlett, and I confess this English Thirteenth-century Polyphony is the first time I have looked at repertory from this period A Facsimile Edition by William J. Summers & Peter M. since I studied Du Fay at university! At that time I also Lefferts sang quite a lot of (slightly later) English music, so I am not Stainer & Bell, 2016. Early English Church Music, 57 completely unfamiliar with it. I was immediately struck 53pp+349 plates. by the rhythmic complexity and delighted to see that the ISMN 979 0 2202 2405 8; ISBN 978 0 85249 940 5 editions preserve the original note values and avoids bar £180 lines - one might expect this to complicate matters with ligatures and coloration to contend with, but actually it is his extraordinarily opulent volume (approx. 12 laid out in such a beautiful way that everything miraculously inches by 17 and weighing more than seven pounds makes perfect sense. Most of the pieces are in two or three T- apologies for the old school measurements!) is a parts (a fourth part – called “Tenor bassus” – is added to marvel to behold. The publisher has had to use glossy paper the Credo of Bedingham’s Mass Dueil angoisseux in only in order to give the best possible colour reproductions of one of the sources). -

Psalms of Praise: “Pesukei Dezimra ”

Dr. Yael Ziegler Pardes The Psalms 1 Psalms of Praise: “Pesukei DeZimra” 1) Shabbat 118b אמר רבי יוסי: יהא חלקי מגומרי הלל בכל יום. איני? והאמר מר: הקורא הלל בכל יום - הרי זה מחרף ומגדף! - כי קאמרינן - בפסוקי דזמרא R. Yosi said: May my portion be with those who complete the Hallel every day. Is that so? Did not the master teach: “Whoever recites the Hallel every day, he is blaspheming and scoffing?” [R. Yosi explained:] When I said it, it was regarding Pesukei DeZimra. Rashi Shabbat 118b הרי זה מחרף ומגדף - שנביאים הראשונים תיקנו לומר בפרקים לשבח והודיה, כדאמרינן בערבי פסחים, )קיז, א(, וזה הקוראה תמיד בלא עתה - אינו אלא כמזמר שיר ומתלוצץ. He is blaspheming and scoffing – Because the first prophets establish to say those chapters as praise and thanks… and he who recites it daily not in its proper time is like one who sings a melody playfully. פסוקי דזמרא - שני מזמורים של הילולים הללו את ה' מן השמים הללו אל בקדשו . Pesukei DeZimra – Two Psalms of Praise: “Praise God from the heavens” [Psalm 148]; “Praise God in His holiness” [Psalm 150.] Massechet Soferim 18:1 Dr. Yael Ziegler Pardes The Psalms 2 אבל צריכין לומר אחר יהי כבוד... וששת המזמורים של כל יום; ואמר ר' יוסי יהא חלקי עם המתפללים בכל יום ששת המזמורים הללו 3) Maharsha Shabbat 118b ה"ז מחרף כו'. משום דהלל נתקן בימים מיוחדים על הנס לפרסם כי הקדוש ברוך הוא הוא בעל היכולת לשנות טבע הבריאה ששינה בימים אלו ...ומשני בפסוקי דזמרה כפירש"י ב' מזמורים של הלולים כו' דאינן באים לפרסם נסיו אלא שהם דברי הלול ושבח דבעי בכל יום כדאמרי' לעולם יסדר אדם שבחו של מקום ואח"כ יתפלל וק"ל: He is blaspheming. -

Jazz Psalms Sheet Music

Sheet Music for Featuring: Lead sheets (including melody and chords) Overhead masters Introductory notes Transcribed by Ron Rienstra Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 3 1. Psalm 100 – Make a Joyful Noise ............................................................................. 5 2a. Psalm 139 – You Created My Innermost Being ...................................................... 7 2b. Psalm 139 – You Created My Innermost Being (in a higher key) ...................... 9 3. Psalm 63 – My Soul Thirsts for God ....................................................................... 11 4a. Psalm 119 – Your Promise Preserves My Life ....................................................... 13 4b. Psalm 119 – Your Promise Preserves My Life (in a higher key) ....................... 15 5. Psalm 79 – Help Us, O God Our Savior, ............................................................... 17 6. Psalm 27 – The Lord Is My Light and My Stronghold ....................................... 19 7a. Psalm 92 – Though the Wicked Spring Up Like Grass ....................................... 21 7b. Psalm 92 – Though the Wicked Spring Up Like Grass (in a higher key) ....... 23 8. Psalm 51 – Wash Me, O God ..................................................................................... 25 9a. Psalm 85 – He Promises Peace to His People ....................................................... 27 9b. Psalm 85 – He Promises Peace to His People (in a higher -

Created to Worship by Norma Jewell & Eva Gibson

KEEP CALM AND WORSHIP ON Colossians 3:16-17 ¹⁶Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly, teaching and admonishing one another in all wisdom, singing psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, with thankfulness in your hearts to God. ¹⁷And whatever you do, in word or deed, do everything in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through him. What is Worship? “…our response to God… by our words and actions that He is worthy of our deepest love.” - Created to Worship by Norma Jewell & Eva Gibson “This people honors me with their lips, But their heart is far from me; In vain do they worship me, Teaching as doctrines the commandments of men.” ~Matthew 15:8-9 What is Worship? The heart matters. Triple A: Affection | Attention | Admiration Ways of Worship - Dancing ¹⁴Wearing a linen ephod, David was dancing before the Lord with all his might, ¹⁵while he and all Israel were bringing up the ark of the Lord with shouts and the sounds of trumpets. ~2 Samuel 6:14-15 ESV Ways of Worship - Prayer ⁵“And when you pray, you must not be like the hypocrites. For they love to stand and pray in the synagogues and at the street corners, that they may be seen by others…⁶But when you pray, go into your room and shut the door and pray to your Father…⁹Pray then like this…Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name.” ~ Matthew 6:5-6 & 9 ESV & KJV Ways of Worship - Tithing “Bring the full tithe into the storehouse, that there may be food in my house. -

Programmbuch Festtage Alte Musik Basel

Basel, 23. bis 31. August 2013 Programmbuch Festtage Alte Musik Basel Wege zum Barock – Tradition und Avantgarde um 1600 www.festtage-basel.ch Titel: Pieter Lastman (1583–1633), David im Tempel, 1618, signiert und datiert, Holz, 1 79 cm x 117 cm, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Braunschweig Zum Geleit Mit der grössten Freude stelle ich der zweiten Edition der Festtage Alte Musik Basel diesen Gruss voran! Die Freude betrifft zuerst die Tatsache, dass die «Kulturstadt Basel» mit sol- chen Ereignissen eine «Fes- tivalstadt» par excellence ist, in der ein hervorragen- des Potenzial an Kreativität herrscht. Grund zur Freu- de ist auch die Bereiche- rung des grossen Gebiets Abdruck mit Quellenangabe erwünscht der Alten Musik, die seit © 2013 Paul Sachers Zeiten einen Verein zur Förderung Basler Absolventen Schwerpunkt des hiesigen auf dem Gebiet der Alten Musik Musiklebens darstellt. Aber Dornacherstrasse 161 A, CH-4053 Basel auch das Auftreten vieler Telefon +41 (0)61 361 03 54 berühmter europäischer En- CH17 0840 1016 1968 0160 3 sembles in Basel, die ohne dieses Festival hier nicht [email protected] zu hören wären, ist sehr lo- www.festtage-basel.ch benswert. Besonders erfreu- Redaktion: Jörg Fiedler, Peter Reidemeister lich ist aber das klare Profil Satz, Gestaltung: Buser, Kommunikation GmbH, Basel des Programms, das höchste Dr. Guy Morin, Regierungspräsident Druck: Druckerei Dietrich AG, Basel Qualität mit der Förderung des Kantons Basel-Stadt des Basler Nachwuchses verbindet: Wer in dieser Stadt Festtage Basel seine Ausbildung durchlaufen und diesem hohen Stan- Geschäftsleitung: Renato D. Pessi Künstlerische Leitung: Peter Reidemeister dard standgehalten hat, der hat es auch verdient, dass er hier mit Engagements zu solchen Ereignissen wei- Preis: 10 Franken terhin Unterstützung erfährt. -

ADORATIO.-Over-Heiligen-Martelaren-En-Geliefden.Pdf

Inhoudstafel Voorwoord | Philip Heylen 9 Laus Polyphoniae 2017 | dag aan dag 13 Introductie | Bart Demuyt 23 Essays Verering van de maagd Maria en het Kind in muziek uit de middeleeuwen en de renaissance | David J. Rothenberg 29 Romance met de roos: de minnekunst in het middeleeuwse en renaissancelied | Jane Alden 125 Een andere Petrarca: Italiaanse renaissancemuziek en Petrarca’s poëzie | Marc Vanscheeuwijck 195 Trahe me post te: muziek, gemeenschap en devotie in het vroegmoderne katholicisme | Daniele V. Filippi 305 Concerten VR 18/08/17 20.00 Stile Antico 41 ZA 19/08/17 10.00 IYAP-concertwandeling 53 11.00 Alexandra Aerts, Lieselot De Wilde & Sofie Vanden Eynde 83 16.00 Alexandra Aerts, Lieselot De Wilde & Sofie Vanden Eynde 83 20.00 Patrizia Bovi, Fadia Tomb El-Hage & Friends 85 22.15 Huelgas Ensemble 101 ZO 20/08/17 10.00 IYAP-concertwandeling 53 11.00 Alexandra Aerts, Lieselot De Wilde & Sofie Vanden Eynde 83 16.00 Alexandra Aerts, Lieselot De Wilde & Sofie Vanden Eynde 83 20.00 Cappella Pratensis, Flanders Boys Choir & Wim Diepenhorst 115 4 5 MA 21/08/17 13.00 Ensemble Leones 141 Radio-uitzending, cursussen, lezingen 20.00 Mala Punica 151 KlaraLive@LausPolyphoniae 27 22.15 Stile Antico 149 Ad tempo taci | filmdocumentaire met Marco Beasley 175 Petrarca & music | lezing door Marc Van Scheeuwijck 217 DI 22/08/17 13.00 VivaBiancaLuna Biffi & Pierre Hamon 165 Mariadevotie en heiligenverering in de late middeleeuwen | cursus 253 20.00 Vox Luminis 179 Isola Idola | muziekvakantie voor kinderen & jongeren 303 22.15 Zefiro Torna & Frank -

The Daily Morning Service

The Daily Morning Service - Bir-kot Ha-Shachar, Blessings of Dawn This section contains the blessings for the ritual garments usually worn during prayer – tallit and tefilin. SS Hebrew Name Description/Thoughts 2 Modeh Ani, I Give Thanks 4 …L’hit-a-teyf Ba-tzit-tzit, To engulf oneself in tzitzit 4 …L’ha-niach tefilin, to place tefilin (for the arm) 4 …Al Mitzvat tefilin, concerning the mitzvah of tefilin (for the head) 6 V’ay-ris-tich Li L’Olam, I will betroth you to me forever 6 ...Asher Yatzar, Who formed (humanity with wisdom) 6 …La-Asok B’Divrei Torah, To be occupied with words of Torah 8 Elohai Neshama, Almighty, the soul (which you have given me is pure) 10 …Asher Natan La-Shich-vei…, Who has Given to the rooster (the ability to distinguish day from night) 23 Shir Shel Yom. A different Psalm for each day of the week. Sunday’s is on Page 23 of Sim Shalom 50 (Psalm 30) Mizmor Shir Hanukat Ha Bayit, A Song for the Dedication of the Temple 52 Kadish Yitom, Mourners Kaddish P’sukei d’Zimra, Verses of Song SS Hebrew Name Description/Thoughts 54 Baruch she’amar, Blessed is the One who spoke (and the world came into being) 54 Chronicles 16:8-36, which describes David bringing the Ark into Jerusalem 58 A mixture of verses from psalms, beginning with Romemu (exalt God) 60 (Psalm 100) Mizmor L’Todah, A Song of Thanks 80 Mixture of Biblical Verses 80 (Psalm 145) Ashrei; For its use in the liturgy, two lines are added to Psalm 145. -

An Italian Tune in the Synagogue: an Unexplored Contrafactum by Leon Modena∗

Kedem G OLDEN AN ITALIAN TUNE IN THE SYNAGOGUE: AN UNEXPLORED CONTRAFACTUM BY LEON MODENA∗ ABSTRACT Leon Modena, one of the celebrated personalities of Italian Jewry in the early modern period, is known for his extensive, life-long involvement with music in its various theoretical and practical aspects. The article presents additional evidence that has gone unnoticed in previous studies of Modena’s musical endeavors: his adaption of a polyphonic, secular Italian melody, for the singing of a liturgical hymn. After identifying the melody and suggesting a possible date for the compo- sition of the Hebrew text, the article proceeds to discuss it in a broader context of the Jewish musical culture at the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, in particular contemporary Jewish views to the use of “foreign” melodies in the syna- gogue. The article concludes with an attempt to situate it as part of Modena’s thought of art music. RÉSUMÉ Léon Modène, une des personnalités célèbres du judaïsme italien du début de la période moderne, est connu pour s’être impliqué de près dans le monde de la musique et ses divers aspects, aussi bien théoriques que pratiques. Le présent article présente un exemple supplémentaire de cette implication, passé inaperçu dans les études antérieures: l’adaptation par Modène d’une mélodie polyphonique profane italienne en un hymne liturgique. Après avoir identifié la mélodie et suggéré la date éventuelle de la composition du texte hébreu, l’article analyse cet hymne dans le contexte plus large de la culture musicale juive au tournant des XVIe et XVIIe siècles, notamment en tenant compte des opinions juives contemporaines sur l’usage de chants «étrangers «dans la synagogue. -

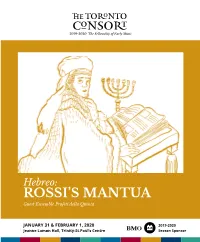

Hebreo: Rossi's Mantua House Program

2019-2020: The Fellowship of Early Music Hebreo: ROSSI’S MANTUA Guest Ensemble Profeti della Quinta JANUARY 31 & FEBRUARY 1, 2020 2019-2020 Jeanne Lamon Hall, Trinity-St.Paul’s Centre Season Sponsor THANK YOU! This production is made possible by The David Fallis Fund for Culture Bridging Programming It is with sincere appreciation and gratitude that we salute the following supporters of this fund: Anonymous (2) Matthew & Phyllis Airhart Michelle & Robert Knight Rita-Anne Piquet The Pluralism Fund Join us at our Intermission Café! The Toronto Consort is happy to offer a wide range of refreshments: BEVERAGES SNACKS PREMIUM ($2) ($2) BAKED GOODS ($2.50) Coffee Assortment of Chips Assortment by Tea Assortment of Candy Bars Harbord Bakery Coke Breathsavers Diet Coke Halls San Pellegrino Apple Juice Pre-order in the lobby! Back by popular demand, pre-order your refreshments in the lobby and skip the line at intermission! PROGRAM The Songs of Salomon HaShirim asher liShlomo Music by Salomone Rossi and Elam Rotem Salomone Rossi Lamnatséah ‘al hagitít Psalm 8 (c.1570-1630) Elohím hashivénu Psalm 80:4, 8, 20 Elam Rotem Kol dodí hineh-zéh bá Song of Songs 2: 8-13 Siméni chachotám al libécha Song of Songs 8: 6-7 Girolamo Kapsperger Passacaglia (ca. 1580-1651) Salomone Rossi Shir hama’alót, ashréy kol yeré Adonái Psalm 128 Hashkivénu Evening prayer Elam Rotem Shechoráh aní venaváh Song of Songs 1: 5-7 Aní yeshenáh velibí er Song of Songs 5:2-16, 6:1-3 INTERMISSION – Join us for the Intermission Café, located in the gym. -

Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs: the Master Musician’S Melodies

Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs: The Master Musician’s Melodies Bereans Adult Bible Fellowship Placerita Baptist Church 2009 by William D. Barrick, Th.D. Professor of OT, The Master’s Seminary Psalm 146 — Entering the Final Hallel 1.0 Introducing Psalm 146 y The Psalter’s “Final Hallel” consists of five psalms (Pss 146–150) that each begin and end with “Hallelujah” (= “Praise the LORD”). y Psalm 146’s praise focuses on the trustworthiness of the LORD Who, in contrast to transient human leaders, always controls His creation for the good of His people. 2.0 Reading Psalm 146 (NAU) 146:1 Praise the LORD! Praise the LORD, O my soul! 146:2 I will praise the LORD while I live; I will sing praises to my God while I have my being. 146:3 Do not trust in princes, In mortal man, in whom there is no salvation. 146:4 His spirit departs, he returns to the earth; In that very day his thoughts perish. 146:5 How blessed is he whose help is the God of Jacob, Whose hope is in the LORD his God, 146:6 Who made heaven and earth, The sea and all that is in them; Who keeps faith forever; 146:7 Who executes justice for the oppressed; Who gives food to the hungry. The LORD sets the prisoners free. Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs 2 Barrick, Placerita Baptist Church 2009 146:8 The LORD opens the eyes of the blind; The LORD raises up those who are bowed down; The LORD loves the righteous; 146:9 The LORD protects the strangers; He supports the fatherless and the widow, But He thwarts the way of the wicked. -

Know His Character Praising, Trusting, & Imitating the God of Justice & Mercy

Know His Character Praising, Trusting, & Imitating the God of Justice & Mercy Psalm 146 This week I’ve been reading about Martin Luther King Jr. Though I don’t agree with everything that Dr. King believed, said, or did, he continues to inspire me. His particular belief in the imago dei (the name of our church and title of this series) drove much of the civil rights movement, as noted by Richard Willis’ book Martin Luther King Jr. and the Image of God. Dr. King believed that every person was created by God, and worthy of dignity, love, basic human rights, and fair and just treatment. He fought for equality and called out those who discriminated against races. He said of the imago dei: “You see the founding fathers were really influenced by the Bible. The whole concept of the imago dei … is the idea that all men have something within them that God injected. Not that they have substantial unity with God, but that every man has a capacity to have fellowship with God. And this gives him uniqueness…. There are no gradations in the image of God. Every man from a treble white to a bass black is significant on God’s keyboard, precisely because every man is made in the image of God. One day we will learn that. We will know one day that God made us to live together as brothers and to respect the dignity and worth of every man. This is why we must fight segregation with all of our non-violent might.” (sermon, 1965, Ebenezer Baptist Church) He called out the church for not living out this belief, and for not worshiping together.