"Auld Lang Syne" G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF 8.01 MB

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Imagining Scotland in Music: Place, Audience, and Attraction Paul F. Moulton Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC IMAGINING SCOTLAND IN MUSIC: PLACE, AUDIENCE, AND ATTRACTION By Paul F. Moulton A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Paul F. Moulton defended on 15 September, 2008. _____________________________ Douglass Seaton Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Eric C. Walker Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member _____________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Alison iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In working on this project I have greatly benefitted from the valuable criticisms, suggestions, and encouragement of my dissertation committee. Douglass Seaton has served as an amazing advisor, spending many hours thoroughly reading and editing in a way that has shown his genuine desire to improve my skills as a scholar and to improve the final document. Denise Von Glahn, Michael Bakan, and Eric Walker have also asked pointed questions and made comments that have helped shape my thoughts and writing. Less visible in this document has been the constant support of my wife Alison. She has patiently supported me in my work that has taken us across the country. She has also been my best motivator, encouraging me to finish this work in a timely manner, and has been my devoted editor, whose sound judgement I have come to rely on. -

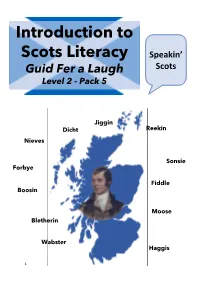

Introduction to Scots Literacy

Introduction to Scots Literacy Speakin’ Scots Guid Fer a Laugh Level 2 - Pack 5 Jiggin Dicht Reekin Nieves Sonsie Forbye Fiddle Boosin Moose Bletherin Wabster Haggis 1 Introduction to Guid Fer A Laugh We are part of the City of Edinburgh Council, South West Adult Learning team and usually deliver ‘Guid Fer a Laugh’ sessions for community groups in South West Edinburgh. Unfortunately, we are unable to meet groups due to Covid-19. Good news though, we have adapted some of the material and we hope you will join in at home. Development of Packs We plan to develop packs from beginner level 1 to 5. Participants will gradually increase in confidence and by level 5, should be able to: read, recognise, understand and write in Scots. Distribution During Covid-19 During Covid-19 restrictions we are emailing packs to community forums, organisations, groups and individuals. Using the packs The packs can be done in pairs, small groups or individually. They are being used by: families, carers, support workers and individuals. The activities are suitable for all adults but particularly those who do not have access to computer and internet. Adapting Packs The packs can be adapted to suit participants needs. For example, the Pilmeny Development Project used The Scot Literacy Pack as part of a St Andrews Day Activity Pack which was posted out to 65 local older people. In the pack they included the Scot Literacy Pack 1 and 2, crosswords, short bread and a blue pen. Please see photo. 2 The Aims of the Session – Whit’s it a’aboot? • it’s about learning Scots language and auld words • takes a look at Scots comedy, songs, poetry and writing • hae a guid laugh at ourselves and others Feedback fae folk This is pack number five and we move on a little to Level 2. -

A Discography of Robert Burns 1948 to 2002 Thomas Keith

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 33 | Issue 1 Article 30 2004 A Discography of Robert Burns 1948 to 2002 Thomas Keith Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Keith, Thomas (2004) "A Discography of Robert Burns 1948 to 2002," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 33: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol33/iss1/30 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas Keith A Discography of Robert Bums 1948 to 2002 After Sir Walter Scott published his edition of border ballads he came to be chastised by the mother of James Hogg, one Margaret Laidlaw, who told him: "There was never ane 0 my sangs prentit till ye prentit them yoursel, and ye hae spoilt them awthegither. They were made for singing an no forreadin: butye hae broken the charm noo, and they'll never be sung mair.'l Mrs. Laidlaw was perhaps unaware that others had been printing Scottish songs from the oral tradition in great numbers for at least the previous hundred years in volumes such as Allan Ramsay's The Tea-Table Miscellany (1723-37), Orpheus Caledonius (1733) compiled by William Thompson, James Oswald's The Cale donian Pocket Companion (1743, 1759), Ancient and Modern Scottish Songs (1767, 1770) edited by David Herd, James Johnson's Scots Musical Museum (1787-1803) and A Select Collection of Original Scotish Airs (1793-1818) compiled by George Thompson-substantial contributions having been made to the latter two collections by Robert Burns. -

ROBERT BURNS and FRIENDS Essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows Presented to G

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Robert Burns and Friends Robert Burns Collections 1-1-2012 ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy Patrick G. Scott University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Kenneth Simpson See next page for additional authors Publication Info 2012, pages 1-192. © The onC tributors, 2012 All rights reserved Printed and distributed by CreateSpace https://www.createspace.com/900002089 Editorial contact address: Patrick Scott, c/o Irvin Department of Rare Books & Special Collections, University of South Carolina Libraries, 1322 Greene Street, Columbia, SC 29208, U.S.A. ISBN 978-1-4392-7097-4 Scott, P., Simpson, K., eds. (2012). Robert Burns & Friends essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy. P. Scott & K. Simpson (Eds.). Columbia, SC: Scottish Literature Series, 2012. This Book - Full Text is brought to you by the Robert Burns Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Burns and Friends by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Author(s) Patrick G. Scott, Kenneth Simpson, Carol Mcguirk, Corey E. Andrews, R. D. S. Jack, Gerard Carruthers, Kirsteen McCue, Fred Freeman, Valentina Bold, David Robb, Douglas S. Mack, Edward J. Cowan, Marco Fazzini, Thomas Keith, and Justin Mellette This book - full text is available at Scholar Commons: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/burns_friends/1 ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy G. Ross Roy as Doctor of Letters, honoris causa June 17, 2009 “The rank is but the guinea’s stamp, The Man’s the gowd for a’ that._” ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. -

November 2020

‘The Vision’ The Robert Burns World Federation Newsletter Issue 47 November 2020 I have decided to give the newsletter the title of ‘The Vision’ as a nod to Burns’s poem of that name in which he bemoans the lack of recognition for poets from his native Ayrshire. His vision involves the appearance the muse Coila. However, the critic David Daiches remarked that ‘the poet does not quite know what to do with her when he brought her in.’ In composing this edition of the newsletter, I felt much the same as I didn’t know what I was going to do about the lack of copy which normally flows in unsolicited from around the world. Fortunately, my colleagues on the Board came up trumps and offered various leads for suitable material. It is a pleasure to report on a very successful Tamfest which explored Burns’s famous poem Tam o’ Shanter in great depth. The importance of music in relation to Burns also comes across strongly with a couple of articles highlighting his continuing influence on contemporary performers. Editor In this Issue: Page Halloween - Profile of President Marc Sherland 1-2 - A New Tartan for the Federation 2 Amang the bonie winding banks, - Lesley McDonald elected at President of LABC 2 Where Doon rins, wimpling, clear; - Tamfest 2020 3 - Simon Lamb Performance Poet 3 Where Bruce ance ruled the martial ranks, - Singer Lauren McQuistin 4-5 An’ shook his Carrick spear; - Heritage Item, Burns’s Mother’s Well 5 Some merry, friendly, country-folks - 200 Club 6 - New Burns Selection for Every Day 6 Together did convene, - St Andrew’s Day Lecture 6 To burns their nits, an’ pou their stocks, - Volunteers for Ellisland 7 An’ haud their Hallowe’en - Habbie Poetry Competition 8 - Federation Yule Concert 9 Fu’ blythe that night. -

Comprehension – Robert Burns – Y5m/Y6d – Brainbox Remembering Burns Robert Burns May Be Gone, but He Will Never Be Forgotten

Robert Burns Who is He? Robert Burns is one of Scotland’s most famous poets and song writers. He is widely regarded as the National Poet of Scotland. He was born in Ayrshire on the 25th January, 1759. Burns was from a large family; he had six other brothers and sisters. He was also known as Rabbie Burns or the Ploughman Poet. Childhood Burns was the son of a tenant farmer. As a child, Burns had to work incredibly long hours on the farm to help out. This meant that he didn’t spend much time at school. Even though his family were poor, his father made sure that Burns had a good education. As a young man, Burns enjoyed reading poetry and listening to music. He also enjoyed listening to his mother sing old Scottish songs to him. He soon discovered that he had a talent for writing and wrote his first song, Handsome Nell, at the age of fifteen. Handsome Nell was a love song, inspired by a farm servant named Nellie Kilpatrick. Becoming Famous In 1786, he planned to emigrate to Jamaica. His plans were changed when a collection of his songs and poems were published. The first edition of his poetry was known as the Kilmarnock edition. They were a huge hit and sold out within a month. Burns suddenly became very popular and famous. That same year, Burns moved to Edinburgh, the capital city of Scotland. He was made very welcome by the wealthy and powerful people who lived there. He enjoyed going to parties and living the life of a celebrity. -

Robert Burns and a Red Red Rose Xiaozhen Liu North China Electric Power University (Baoding), Hebei 071000, China

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 311 1st International Symposium on Education, Culture and Social Sciences (ECSS 2019) Robert Burns and A Red Red Rose Xiaozhen Liu North China Electric Power University (Baoding), Hebei 071000, China. [email protected] Abstract. Robert Burns is a well-known Scottish poet and his poem A Red Red Rose prevails all over the world. This essay will first make a brief introduction of Robert Burns and make an analysis of A Red Red Rose in the aspects of language, imagery and rhetoric. Keywords: Robert Burns; A Red Red Rose; language; imagery; rhetoric. 1. Robert Burns’ Life Experience Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796) is a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is one of the most famous poets of Scotland and is widely regarded as a Scottish national poet. Being considered as a pioneer of the Romantic Movement, Robert Burns became a great source of inspiration to the founders of both liberalism and socialism after his death. Most of his world-renowned works are written in a Scots dialect. And in the meantime, he produced a lot of poems in English. He was born in a peasant’s clay-built cottage, south of Ayr, in Alloway, South Ayrshire, Scotland in 1759 His father, William Burnes (1721–1784), is a self-educated tenant farmer from Dunnottar in the Mearns, and his mother, Agnes Broun (1732–1820), is the daughter of a Kirkoswald tenant farmer. Despite the poor soil and a heavy rent, his father still devoted his whole life to plough the land to support the whole family’s livelihood. -

The Prayer of Holy Willie

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications English Language and Literatures, Department of 7-7-2015 The rP ayer of Holy Willie: A canting, hypocritical, Kirk Elder Patrick G. Scott University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/engl_facpub Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Publication Info Published in 2015. Introduction and editorial matter copyright (c) Patrick Scott nda Scottish Poetry Reprint Series, 2015. This Book is brought to you by the English Language and Literatures, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PRAYER OF HOLY WILLIE by ROBERT BURNS Scottish Poetry Reprints Series An occasional series edited by G. Ross Roy, 1970-1996 1. The Life and Death of the Piper of Kilbarchan, by Robert Semphill, edited by G. Ross Roy (Edinburgh: Tragara Press, 1970). 2. Peblis, to the Play, edited by A. M. Kinghorn (London: Quarto Press, 1974). 3. Archibald Cameron’s Lament, edited by G. Ross Roy (London: Quarto Press, 1977). 4. Tam o’ Shanter, A Tale, by Robert Burns, ed. By G. Ross Roy from the Afton Manuscript (London: Quarto Press, 1979). 5. Auld Lang Syne, by Robert Burns, edited by G. Ross Roy, music transcriptions by Laurel E. Thompson and Jonathan D. Ensiminger (Greenock: Black Pennell Press, 1984). 6. The Origin of Species, by Lord Neaves, ed. Patrick Scott (London: Quarto Press, 1986). 7. Robert Burns, A Poem, by Iain Crichton Smith (Edinburgh: Morning Star, 1996). -

A Poem Ne Ly Sprung in Fairvie

A Poem Ne ly Sprung in Fairvie by CLARK AYCOCK ave you ever sung “Auld Lang therefore able to write in the local Ayrshire Syne” on New Year’s Eve? dialect, as well as in “Standard” English. He Or have you ever uttered the wrote many romantic poems that are still phrase, when frustrated, “the recited and sung today, and some of us may best-laid schemes of mice and men…”? remember his songs more easily than we do Did you know that John Steinbeck’s classic his poetry. in a human book Of Mice and Men was based on a line Robert Burns infl uenced many other head, though I in a poem written “To a Mouse”... or that poets including Wordsworth, Coleridge have seen the most a Tam O’ Shanter cap was named aft er a distinguished men of my time.” and Shelley. Walter Scott was also a great A commemorative plate showing character in a poem by that name? And admirer and wrote this wonderful descrip- In the late 1700s, many Scots migrated did you know that singer and songwriter tion of Burns that provides us with a clear from the Piedmont into the mountains of Robert Burns in the center Bob Dylan said his biggest creative impression of the man. “His person was WNC, bringing with them their country's surrounded by characters from inspiration was the poem and song “A strong and robust; his manners rustic, not culture and craft and inherent connection his poems Red, Red Rose”? Yes, we are talking about clownish, a sort of dignifi ed plainness and with Burns. -

The Coulter Collection of Burns Manuscripts

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 24 | Issue 1 Article 7 1989 The oultC er Collection of Burns Manuscripts lain G. Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Brown, lain G. (1989) "The oultC er Collection of Burns Manuscripts," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 24: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol24/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. lain G. Brown The Coulter Collection of Burns Manuscripts In the Department of Manuscripts of the National Library of Scotland we are fairly used to members of the public bringing in for an opinion documents which they believe to be original manuscripts of Robert Burns. Some of these tum out to be common and well-known facsimiles, often framed behind dirty glass_"Robert Bruce's March to Bannockburn" is an outstanding example. Many are the owners who go away clutching their "Scots wha hae... " from great-granny's living-room wall, disappointed to be told that what they have is only a reproduction. Then there are the cele brated Alexander Howland ('Antique') Smith forgeries. These are more confusing as they are, unlike a facsimile, intended to deceive. They have to be examined patiently for tell-tale details such as the use of a steel pen, or the presence of letter-forms a little too laboured; or until one is sure that the strange, indefinable feeling of the thing being just wrong is indeed the proper judgement. -

The Songs of Robert Burns

— : IX. MISCELLANEOUS 473 have had a personal acquaintance with Clarke, the musical editor of the Museum, and that Stenhouse himself communicated to Hogg the ' genuine copy of the air ' which consists principally in leaving out the accidental sharps. The modem set of the air differs from that of the original as in our text. No. 305. Frae the friends and land I love. Scots Musical Mtiseum, 1792, No. J02. Tune, Carron side. The MS. is in the British Museum. The first of a series of Jacobite songs printed in the fourth volume of the Museum. ' In the Interleaved Mtiseum Burns says of the present verses : I added the four last lines by way of giving a turn to the theme of the poem, such as it is.' No other song of the kind has been discovered, and I have failed to find it. The present verses were printed in the Museum with a bad copy of the tune Can-on side. The music in the text is taken from the Caledonian Pocket Cotn- ' panion, c. 1 756, viii. 10, there designated a plaintive air,' which was originally published in 1740. ITo. 306. A.S I came o'er the Cairney mount. Scots Musical Museum, 1796, No. 46"], signed 'Z.' Centenary Burns, 1897, iii. i']i. The MS. is in the British Museum. The fragment is a much revised version of an old song of four stanzas in the Merry Muses. The tune was first printed as The highland lassie in Oswald's Curious Collection of Scots Tttnes, 1740,^7 ; it is in Caledonian Pocket Companion, 1743, i. -

The Songs of Robert Burns

BIBLIOGRAPHY I. WORKS OF BURNS. [Burns was born January 25, 1759 ; he wrote his first song in the autumn of first 1773 or 1774 ; published the edition of his Works in 1786, and the last in 1794. His connexion with Johnson's Scots Musical Museum began in the spring or summer of 1787, and with Thomson's Scotish Airs in September, 1792, and he continued to contribute to both collections until his death on July 21, 1796. The Bibliography of Burns in the ' Memorial Catalogue of the Bums Exhibition, 1896. Glasgow: Hodge, 1898,' describes 696 editions of the Works of Bums published in the United Kingdom.] Hastie MSS., in the British Museum (No. 22,307), include 162 songs, mostly in the handwriting of Burns, which he contributed to the Scots Musical MtiseufH. Dalhousie MS., in Brechin Castle, consists of Letters to George Thomson, and songs intended for publication in Scotish Airs. Gray's MS. Lists, belonging to George Gray, Esq., of the Coimty Buildings, Glasgow, are a number of detached sheets containing the titles of songs pro- posed for insertion in the second and subsequent volumes of the Scots Musical Museum. The lists are partly in the handwriting of Burns and partly in that of James Johnson. Law's MS. List, lately in the possession of William Law, Littleborough, is a holograph of Burns, entitled ' List of Songs for 3rd Volume of the Scots Musical Mtiseum^ which he sent to Johnson in a letter dated April 24, 1789. This MS., now referred to for the first time, definitely settles the authorship of many songs, some of which in the following pages are printed for the first time as the work of Burns.