The Songs of Robert Burns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Letters of Robert Burns 1

The Letters of Robert Burns 1 The Letters of Robert Burns The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Letters of Robert Burns, by Robert Burns #3 in our series by Robert Burns Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. The Letters of Robert Burns 2 **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: The Letters of Robert Burns Author: Robert Burns Release Date: February, 2006 [EBook #9863] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on October 25, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LETTERS OF ROBERT BURNS *** Produced by Charles Franks, Debra Storr and PG Distributed Proofreaders BURNS'S LETTERS. THE LETTERS OF ROBERT BURNS, SELECTED AND ARRANGED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION, BY J. -

Download PDF 8.01 MB

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Imagining Scotland in Music: Place, Audience, and Attraction Paul F. Moulton Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC IMAGINING SCOTLAND IN MUSIC: PLACE, AUDIENCE, AND ATTRACTION By Paul F. Moulton A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Paul F. Moulton defended on 15 September, 2008. _____________________________ Douglass Seaton Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Eric C. Walker Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member _____________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Alison iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In working on this project I have greatly benefitted from the valuable criticisms, suggestions, and encouragement of my dissertation committee. Douglass Seaton has served as an amazing advisor, spending many hours thoroughly reading and editing in a way that has shown his genuine desire to improve my skills as a scholar and to improve the final document. Denise Von Glahn, Michael Bakan, and Eric Walker have also asked pointed questions and made comments that have helped shape my thoughts and writing. Less visible in this document has been the constant support of my wife Alison. She has patiently supported me in my work that has taken us across the country. She has also been my best motivator, encouraging me to finish this work in a timely manner, and has been my devoted editor, whose sound judgement I have come to rely on. -

INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, Day Department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 Points)

The elective discipline «INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, day department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 points) Task: Select one British folk ballad from the list below, write your name, perform your individual scientific research paper in writing according to the given scheme and hand your work in to the teacher: Titles of British Folk Ballads Students’ Surnames 1. № 58: “Sir Patrick Spens” 2. № 13: “Edward” 3. № 84: “Bonny Barbara Allen” 4. № 12: “Lord Randal” 5. № 169:“Johnie Armstrong” 6. № 243: “James Harris” / “The Daemon Lover” 7. № 173: “Mary Hamilton” 8. № 94: “Young Waters” 9. № 73:“Lord Thomas and Annet” 10. № 95:“The Maid Freed from Gallows” 11. № 162: “The Hunting of the Cheviot” 12. № 157 “Gude Wallace” 13. № 161: “The Battle of Otterburn” 14. № 54: “The Cherry-Tree Carol” 15. № 55: “The Carnal and the Crane” 16. № 65: “Lady Maisry” 17. № 77: “Sweet William's Ghost” 18. № 185: “Dick o the Cow” 19. № 186: “Kinmont Willie” 20. № 187: “Jock o the Side” 21. №192: “The Lochmaben Harper” 22. № 210: “Bonnie James Campbell” 23. № 37 “Thomas The Rhymer” 24. № 178: “Captain Car, or, Edom o Gordon” 25. № 275: “Get Up and Bar the Door” 26. № 278: “The Farmer's Curst Wife” 27. № 279: “The Jolly Beggar” 28. № 167: “Sir Andrew Barton” 29. № 286: “The Sweet Trinity” / “The Golden Vanity” 30. № 1: “Riddles Wisely Expounded” 31. № 31: “The Marriage of Sir Gawain” 32. № 154: “A True Tale of Robin Hood” N.B. You can find the text of the selected British folk ballad in the five-volume edition “The English and Scottish Popular Ballads: five volumes / [edited by Francis James Child]. -

A Discography of Robert Burns 1948 to 2002 Thomas Keith

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 33 | Issue 1 Article 30 2004 A Discography of Robert Burns 1948 to 2002 Thomas Keith Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Keith, Thomas (2004) "A Discography of Robert Burns 1948 to 2002," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 33: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol33/iss1/30 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas Keith A Discography of Robert Bums 1948 to 2002 After Sir Walter Scott published his edition of border ballads he came to be chastised by the mother of James Hogg, one Margaret Laidlaw, who told him: "There was never ane 0 my sangs prentit till ye prentit them yoursel, and ye hae spoilt them awthegither. They were made for singing an no forreadin: butye hae broken the charm noo, and they'll never be sung mair.'l Mrs. Laidlaw was perhaps unaware that others had been printing Scottish songs from the oral tradition in great numbers for at least the previous hundred years in volumes such as Allan Ramsay's The Tea-Table Miscellany (1723-37), Orpheus Caledonius (1733) compiled by William Thompson, James Oswald's The Cale donian Pocket Companion (1743, 1759), Ancient and Modern Scottish Songs (1767, 1770) edited by David Herd, James Johnson's Scots Musical Museum (1787-1803) and A Select Collection of Original Scotish Airs (1793-1818) compiled by George Thompson-substantial contributions having been made to the latter two collections by Robert Burns. -

ROBERT BURNS and FRIENDS Essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows Presented to G

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Robert Burns and Friends Robert Burns Collections 1-1-2012 ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy Patrick G. Scott University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Kenneth Simpson See next page for additional authors Publication Info 2012, pages 1-192. © The onC tributors, 2012 All rights reserved Printed and distributed by CreateSpace https://www.createspace.com/900002089 Editorial contact address: Patrick Scott, c/o Irvin Department of Rare Books & Special Collections, University of South Carolina Libraries, 1322 Greene Street, Columbia, SC 29208, U.S.A. ISBN 978-1-4392-7097-4 Scott, P., Simpson, K., eds. (2012). Robert Burns & Friends essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy. P. Scott & K. Simpson (Eds.). Columbia, SC: Scottish Literature Series, 2012. This Book - Full Text is brought to you by the Robert Burns Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Burns and Friends by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Author(s) Patrick G. Scott, Kenneth Simpson, Carol Mcguirk, Corey E. Andrews, R. D. S. Jack, Gerard Carruthers, Kirsteen McCue, Fred Freeman, Valentina Bold, David Robb, Douglas S. Mack, Edward J. Cowan, Marco Fazzini, Thomas Keith, and Justin Mellette This book - full text is available at Scholar Commons: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/burns_friends/1 ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy G. Ross Roy as Doctor of Letters, honoris causa June 17, 2009 “The rank is but the guinea’s stamp, The Man’s the gowd for a’ that._” ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. -

The Ballads and Songs of Ayrshire

LIBRARY OF THE University of California. Class VZQlo ' i" /// s Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from Microsoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/balladssongsofayOOpaterich THE BALLADS AND SONGS OF AYRSHIRE, ILLUSTRATED WITH SKETCHES, HISTORICAL, TRADITIONAL, NARRATIVE AND BIOGRAPHICAL. Old King Coul was a merry old soul, And a jolly old soul was he ; Old King Coul he had a brown bowl, And they brought him in fiddlers three. EDINBURGH: THOMAS G. STEVENSON, HISTORICAL AND ANTIQUARIAN BOOKSELLER, 87 PRINCES STREET. MDCCCXLVII. — ; — CFTMS IVCRSI1 c INTRODUCTION. Renfrewshire has her Harp—why not Ayrshire her Lyre ? The land that gave birth to Burns may well claim the distinction of a separate Re- pository for the Ballads and Songs which belong to it. In this, the First Series, it has been the chief object of the Editor to gather together the older lyrical productions connected with the county, intermixed with a slight sprinkling of the more recent, by way of lightsome variation. The aim of the work is to collect those pieces, ancient and modern, which, scattered throughout various publications, are inaccessible to many readers ; and to glean from, oral recitation the floating relics of a former age that still exist in living remembrance, as well as to supply such in- formation respecting the subject or author as maybe deemed interesting. The songs of Burns—save, perhaps, a few of the more rare—having been already collected in numerous editions, and consequently well known, will form no part of the Repository. In distinguishing the Ballads and Songs of Ayrshire, the Editor has been, and will be, guided by the connec- tion they have with the district, either as to the author or subject ; and now that the First Series is before the public, he trusts that, whatever may be its defects, the credit at least will be given Jiim of aiming, how- ever feebly, at the construction of a lasting monument of the lyrical literature of Ayrshire. -

November 2020

‘The Vision’ The Robert Burns World Federation Newsletter Issue 47 November 2020 I have decided to give the newsletter the title of ‘The Vision’ as a nod to Burns’s poem of that name in which he bemoans the lack of recognition for poets from his native Ayrshire. His vision involves the appearance the muse Coila. However, the critic David Daiches remarked that ‘the poet does not quite know what to do with her when he brought her in.’ In composing this edition of the newsletter, I felt much the same as I didn’t know what I was going to do about the lack of copy which normally flows in unsolicited from around the world. Fortunately, my colleagues on the Board came up trumps and offered various leads for suitable material. It is a pleasure to report on a very successful Tamfest which explored Burns’s famous poem Tam o’ Shanter in great depth. The importance of music in relation to Burns also comes across strongly with a couple of articles highlighting his continuing influence on contemporary performers. Editor In this Issue: Page Halloween - Profile of President Marc Sherland 1-2 - A New Tartan for the Federation 2 Amang the bonie winding banks, - Lesley McDonald elected at President of LABC 2 Where Doon rins, wimpling, clear; - Tamfest 2020 3 - Simon Lamb Performance Poet 3 Where Bruce ance ruled the martial ranks, - Singer Lauren McQuistin 4-5 An’ shook his Carrick spear; - Heritage Item, Burns’s Mother’s Well 5 Some merry, friendly, country-folks - 200 Club 6 - New Burns Selection for Every Day 6 Together did convene, - St Andrew’s Day Lecture 6 To burns their nits, an’ pou their stocks, - Volunteers for Ellisland 7 An’ haud their Hallowe’en - Habbie Poetry Competition 8 - Federation Yule Concert 9 Fu’ blythe that night. -

"Auld Lang Syne" G

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Selected Essays on Robert Burns by G. Ross Roy Robert Burns Collections 3-1-2018 "Auld Lang Syne" G. Ross Roy University of South Carolina - Columbia Publication Info 2018, pages 77-83. (c) G. Ross Roy, 1984; Estate of G. Ross Roy; and Studies in Scottish Literature, 2019. First published as introduction to Auld Lang Syne, by Robert Burns, Scottish Poetry Reprints, 5 (Greenock: Black Pennell, 1984). This Chapter is brought to you by the Robert Burns Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Selected Essays on Robert Burns by G. Ross Roy by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “AULD LANG SYNE” (1984) A good case can be made that “Auld Lang Syne” is the best known “English” song in the world, & perhaps the best known in any language if we except national anthems. The song is certainly known throughout the English-speaking world, including countries which were formerly part of the British Empire. It is also known in most European countries, including Russia, as well as in China and Japan. Before and during the lifetime of Robert Burns the traditional Scottish song of parting was “Gude Night and Joy be wi’ You a’,” and there is evidence that despite “Auld Lang Syne” Burns continued to think of the older song as such. He wrote to James Johnson, for whom he was writing and collecting Scottish songs to be published in The Scots Musical Museum (6 vols. Edinburgh, 1787-1803) about “Gude Night” in 1795, “let this be your last song of all the Collection,” and this more than six years after he had written “Auld Lang Syne.” When Johnson published Burns’s song it enjoyed no special place in the Museum, but he followed the poet’s counsel with respect to “Gude Night,” placing it at the end of the sixth volume. -

Robert Burns and a Red Red Rose Xiaozhen Liu North China Electric Power University (Baoding), Hebei 071000, China

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 311 1st International Symposium on Education, Culture and Social Sciences (ECSS 2019) Robert Burns and A Red Red Rose Xiaozhen Liu North China Electric Power University (Baoding), Hebei 071000, China. [email protected] Abstract. Robert Burns is a well-known Scottish poet and his poem A Red Red Rose prevails all over the world. This essay will first make a brief introduction of Robert Burns and make an analysis of A Red Red Rose in the aspects of language, imagery and rhetoric. Keywords: Robert Burns; A Red Red Rose; language; imagery; rhetoric. 1. Robert Burns’ Life Experience Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796) is a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is one of the most famous poets of Scotland and is widely regarded as a Scottish national poet. Being considered as a pioneer of the Romantic Movement, Robert Burns became a great source of inspiration to the founders of both liberalism and socialism after his death. Most of his world-renowned works are written in a Scots dialect. And in the meantime, he produced a lot of poems in English. He was born in a peasant’s clay-built cottage, south of Ayr, in Alloway, South Ayrshire, Scotland in 1759 His father, William Burnes (1721–1784), is a self-educated tenant farmer from Dunnottar in the Mearns, and his mother, Agnes Broun (1732–1820), is the daughter of a Kirkoswald tenant farmer. Despite the poor soil and a heavy rent, his father still devoted his whole life to plough the land to support the whole family’s livelihood. -

The Coulter Collection of Burns Manuscripts

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 24 | Issue 1 Article 7 1989 The oultC er Collection of Burns Manuscripts lain G. Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Brown, lain G. (1989) "The oultC er Collection of Burns Manuscripts," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 24: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol24/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. lain G. Brown The Coulter Collection of Burns Manuscripts In the Department of Manuscripts of the National Library of Scotland we are fairly used to members of the public bringing in for an opinion documents which they believe to be original manuscripts of Robert Burns. Some of these tum out to be common and well-known facsimiles, often framed behind dirty glass_"Robert Bruce's March to Bannockburn" is an outstanding example. Many are the owners who go away clutching their "Scots wha hae... " from great-granny's living-room wall, disappointed to be told that what they have is only a reproduction. Then there are the cele brated Alexander Howland ('Antique') Smith forgeries. These are more confusing as they are, unlike a facsimile, intended to deceive. They have to be examined patiently for tell-tale details such as the use of a steel pen, or the presence of letter-forms a little too laboured; or until one is sure that the strange, indefinable feeling of the thing being just wrong is indeed the proper judgement. -

The Songs of Scotland

«& • - ' m¥Hi m THE GLEN COLLECTION OF SCOTTISH MUSIC Presented by Lady DOROTHEA RUGGLES-BRISE to the National Library of Scotland, in memory of her brother, Major Lord George Stewart Murray, Black Watch, killed in action in France in 1914. 28th January 1927. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/songsofscotland02grah A THE SONGS OF SCOTLAND ADAPTED TO THEIR APPROPRIATE MELODIES ARRANGED WITH PIANOFORTE ACCOMPANIMENTS BY G. F. GRAHAM, T. M. MTJDIE, J. T. SURENNE,, H. E. DIBDIN, FINLAY DUN, &c. 3Hu8ttateb n»it^» historical, 55iogra:pfjical, anb Sritical Notices BY GEORGE FARQUHAR GRAHAM, AUTHOR OF THE ARTICLE "MUSIC" IN THE SEVENTH EDITION OP THE ENCYCLOPEDIA EE.ITANNICA, ETC. ETO. VOL III. WOOD AND CO., 12, WATERLOO PLACE, EDINBURGH; J. MUIR CO., BUCHANAN STREET, GLASGOW WOOD AND 42, ; OLIVER & BOYD, EDINBURGH; CRAMER, BEALE, & CHAPPELL, REGENT STREET; CHAPPELL, NEW BOND STREET ; ADDISON & HODSON, REGENT STREET ; J. ALFRED NOVELLO, DEAN STREET; AND SLMPKIN, MARSHALL, & CO., LONDON. MDCCCXLIX. EDINBURGH : PRINTED BY T. CONSTABLE, PRINTER TO IIER MAJESTT. INDEX TO THE FIRST LINES OP THE SONGS IN THE THIRD VOLUME. FAGB - PAGE Accuse me not, inconstant fair, 48 On Cessnock banks, .... 146 Again rejoicing Nature sees, 62 } On Ettrick banks, ae simmer nicht, (App. 168, 169,) 52 And we're a' noddin', nid, nid, noddin', 38 ) O once my thyme was young, (note,) . 85 why leaves thou thy Nelly to ? 56 A piper came to our town, (note and App.) 7,167 \ O Sandy, mourn A rosebud by my early walk, 86 O speed, Lord Nithsdale, .. -

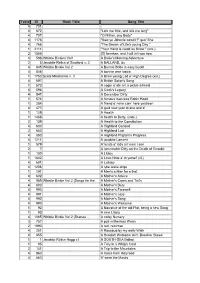

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4 701 - 4 672 "Lo'e me little, and lo'e me lang" 4 707 "O Mither, ony Body" 4 1176 "Saw ye Johnnie comin'?" quo' She 4 766 "The Dream of Life's young Day " 1 2111 "Your Hand is cauld as Snaw " (xxx.) 2 1555 [O] hearken, and I will tell you how 4 596 Whistle Binkies Vol1 A Bailie's Morning Adventure 2 5 Jacobite Relics of Scotland v. 2 A BALLAND, &c 4 845 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 A Bonnie Bride is easy buskit 4 846 A bonnie wee lassie 1 1753 Scots Minstrelsie v. 3 A Braw young Lad o' High Degree (xxi.) 4 597 A British Sailor's Song 1 573 A cogie o' ale an' a pickle aitmeal 4 598 A Cook's Legacy 4 847 A December Dirty 1 574 A famous man was Robin Hood 1 284 A friend o' mine cam' here yestreen 4 477 A guid new year to ane and a' 1 129 A Health 1 1468 A health to Betty, (note,) 2 139 A Health to the Constitution 4 600 A Highland Garland 2 653 A Highland Lad 4 850 A Highland Pilgram's Progress 4 1211 A jacobite Lament 1 579 A' kinds o' lads an' men I see 2 7 A lamentable Ditty on the Death of Geordie 1 130 A Litany 1 1842 A Love-Note a' to yersel' (xi.) 4 601 A Lullaby 4 1206 A lyke wake dirge 1 291 A Man's a Man for a that 4 602 A Mother's Advice 4 989 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Songs for the A Mother's Cares and Toil's 4 603 Nursery) A Mother's Duty 4 990 A Mother's Farewell 4 991 A Mother's Joys 4 992 A Mother's Song 4 993 A Mother's Welcome 1 92 A Narrative of the old Plot; being a new Song 1 93 A new Litany 4 1065 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Scenes … A noisy Nursery 3 757 Nursery) A puir mitherless Wean 2 1990 A red, red rose 4 251 A Rosebud by my early Walk 4 855 A Scottish Welcome to H.