The Ballads and Songs of Ayrshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Letters of Robert Burns 1

The Letters of Robert Burns 1 The Letters of Robert Burns The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Letters of Robert Burns, by Robert Burns #3 in our series by Robert Burns Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. The Letters of Robert Burns 2 **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: The Letters of Robert Burns Author: Robert Burns Release Date: February, 2006 [EBook #9863] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on October 25, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LETTERS OF ROBERT BURNS *** Produced by Charles Franks, Debra Storr and PG Distributed Proofreaders BURNS'S LETTERS. THE LETTERS OF ROBERT BURNS, SELECTED AND ARRANGED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION, BY J. -

The Covenanter

The Covenanter DECEMBER 2013 Fenwick Parish Church Community Magazine no 445 THE COVENANTER December 2013 CHURCH SERVICES – SUNDAYS 10.30am JUNIOR CHURCH and Ycam – 10.30am MINISTER: Rev Geoff Redmayne BSc. B.D., M.Phil, the Manse, 2 Kirkton Place, Fenwick KA3 6DW Telephone 01560 600217 E-mail : [email protected] Session Clerk: Mrs Nora Shanks,12Skernieland Rd, Fenwick Telephone: 01560 600202 E-mail : [email protected] Gift Aid/Freewill Offerings: Mr A.Crosbie Telephone: 01560 322229 4 Campbell Street, Darvel, KA17 0DA Email:[email protected] Church Treasurer: Mrs Tracy Geddes,1 Skernieland Rd Fenwick Telephone 01560 600374 Roll Keeper: Mrs Nora Shanks,12Skernieland Rd, Fenwick Telephone: 01560 600202 E-mail : [email protected] Organist: Alistair Peter, 37 South Hamilton St Kilmarnock, KA1 2DT Email : [email protected] The Covenanter: Production/Distribution: Jean Bowes, 2 Rysland Drive Fenwick Telephone: 01560600259 Convener/ Advertising: Bill McNab, Avrilea, Kingsford, Stewarton . KA3 5JS Telephone 01560 482468 Email:[email protected] Please note new Email address The Covenanter can now be found on the internet as part of the Church website at www.fenwickparishchurch.org.uk/covenanter. All copy for the magazine should be received at least two weeks before the first Sunday of the publication month. Fenwick Parish Church (Church of Scotland) Registered Scottish Charity No SC010062 Covenanter Page 2 When did the “t” go silent? The official publication date of this edition of The Covenanter -

Ayrshire & the Isles of Arran & Cumbrae

2017-18 EXPLORE ayrshire & the isles of arran & cumbrae visitscotland.com WELCOME TO ayrshire & the isles of arran and cumbrae 1 Welcome to… Contents 2 Ayrshire and ayrshire island treasures & the isles of 4 Rich history 6 Outdoor wonders arran & 8 Cultural hotspots 10 Great days out cumbrae 12 Local flavours 14 Year of History, Heritage and Archaeology 2017 16 What’s on 18 Travel tips 20 VisitScotland iCentres 21 Quality assurance 22 Practical information 24 Places to visit listings 48 Display adverts 32 Leisure activities listings 36 Shopping listings Lochranza Castle, Isle of Arran 55 Display adverts 37 Food & drink listings Step into Ayrshire & the Isles of Arran and Cumbrae and you will take a 56 Display adverts magical ride into a region with all things that make Scotland so special. 40 Tours listings History springs to life round every corner, ancient castles cling to spectacular cliffs, and the rugged islands of Arran and Cumbrae 41 Transport listings promise unforgettable adventure. Tee off 57 Display adverts on some of the most renowned courses 41 Family fun listings in the world, sample delicious local food 42 Accommodation listings and drink, and don’t miss out on throwing 59 Display adverts yourself into our many exciting festivals. Events & festivals This is the birthplace of one of the world’s 58 Display adverts most beloved poets, Robert Burns. Come and breathe the same air, and walk over 64 Regional map the same glorious landscapes that inspired his beautiful poetry. What’s more, in 2017 we are celebrating our Year of History, Heritage and Archaeology, making this the perfect time to come and get a real feel for the characters, events, and traditions that Cover: Culzean Castle & Country Park, made this land so remarkable. -

The Governance of the NHS in Scotland - Ensuring Delivery of the Best Healthcare for Scotland Published in Scotland by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body

Published 2 July 2018 SP Paper 367 7th report (Session 5) Health and Sport Committee Comataidh Slàinte is Spòrs The Governance of the NHS in Scotland - ensuring delivery of the best healthcare for Scotland Published in Scotland by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body. All documents are available on the Scottish For information on the Scottish Parliament contact Parliament website at: Public Information on: http://www.parliament.scot/abouttheparliament/ Telephone: 0131 348 5000 91279.aspx Textphone: 0800 092 7100 Email: [email protected] © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliament Corporate Body The Scottish Parliament's copyright policy can be found on the website — www.parliament.scot Health and Sport Committee The Governance of the NHS in Scotland - ensuring delivery of the best healthcare for Scotland, 7th report (Session 5) Contents Introduction ____________________________________________________________1 Staff Governance________________________________________________________3 Staff Governance Standard _______________________________________________3 Monitoring views of NHS Scotland staff______________________________________4 Staff Governance - themes raised in evidence ________________________________4 Pressure on staff - what witnesses told us __________________________________5 Consultation and staff relations __________________________________________6 Discrimination, bullying and harassment _________________________________7 Whistleblowing_________________________________________________________8 Confidence to -

Kilmarnock Living

@^abVgcdX`A^k^c\ 6 H E : 8 > 6 A E A 6 8 : I D A > K : ! L D G @ ! A : 6 G C 6 C 9 : C ? D N ilZcineaVXZhndj]VkZid`cdlVWdji ^c@^abVgcdX`VcY:Vhi6ngh]^gZ The Dean Castle and Country Park, Kilmarnock River Ayr Way, from Glenbuck A phenomenal medieval experience. The Dean Castle is a A unique opportunity for walkers to experience the most glorious wonderfully well-preserved keep and surrounding buildings set in Ayrshire countryside on Scotland’s first source to sea walk. Starting beautifully manicured gardens and Country Park extending to more at Glenbuck, the birthplace of legendary football manager Bill than 480 acres. Shankley, the path travels 44 miles to the sea at Ayr. The Historic Old Town, Kilmarnock Burns House Museum, Mauchline Narrow lanes and unique little boutique shops. There are plenty of Situated in the heart of picturesque Mauchline, the museum was supermarkets and big stores elsewhere in Kilmarnock, but check the first marital home of Robert Burns and Jean Armour. As well as out Bank Street for something really different. being devoted to the life of Scotland’s national poet, the museum The Palace Theatre and Grand Hall, Kilmarnock has exhibits on the village’s other claims to fame – curling stones The creative hub of East Ayrshire. This is where everything from and Mauchline Box Ware. opera companies to pantomimes come to perform. And the hall is a great venue for private events. Kay Park, Kilmarnock Soon to be home to the Burns Monument Centre, this is one of Rugby Park, Kilmarnock the best of Kilmarnock’s public parks. -

Information Bulletin March 2019

INFORMATION BULLETIN MARCH 2019 CONTENTS Service Page No. Environment and Infrastructure Road and Footways Capital Investment Programme 1 - 8 Financial Year 2019/20 Communities, Housing & Planning Services Notices and Licences Issued: 14 November 2018 to 9 - 18 18 February 2019 Delegated Items, Appeals and Building Warrants: 19 - 76 10 December 2018 to 15 February 2019 Finance & Resources Delegated Licensing Applications: 16 January to 77 - 89 31 January 2019 1 of 89 To: INFORMATION BULLETIN On: MARCH 2019 Report by: DIRECTOR OF ENVIRONMENT & INFRASTRUCTURE Heading: ROAD & FOOTWAYS CAPITAL INVESTMENT PROGRAMME, FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/20 1. Summary 1.1 At the Council meeting of 28 February 2019, it was agreed to deliver a £40milion, five-year investment in Renfrewshire roads, cycling routes and pedestrian paths, representing the biggest ever investment of its kind. This will make journeys safer and easier, improve business connectivity, support development and town centre improvements and make it easier for visitors to enjoy Renfrewshire attractions. 1.2 The approach during 2019/20 will continue the progressive improvement of roads assets and fits with the asset management approach of seeking to reduce reactive revenue expenditure through prudent life cycle investment. 1.3 The focus for 2019/20 includes schemes within the strategic road network as well as roads of local significance with a presence in every town and village across Renfrewshire. A sustained effort will continue to ensure the highest quality of product will be used and contractors’ standards will be robustly monitored throughout the year. 1.4 There are a number of strategic roads where works are planned and as such, detailed communication plans will be developed for each of these to ensure stakeholder engagement is maintained going forward. -

The Scottish Nebraskan Newsletter of the Prairie Scots

The Scottish Nebraskan Newsletter of the Prairie Scots Chief’s Message Summer 2021 Issue I am delighted that summer is upon us finally! For a while there I thought winter was making a comeback. I hope this finds you all well and excited to get back to a more normal lifestyle. We are excited as we will finally get to meet in person for our Annual Meeting and Gathering of the Clans in August and hope you all make an effort to come. We haven't seen you all in over a year and a half and we are looking forward to your smiling faces and a chance to talk with all of you. Covid-19 has been rough on all of us; it has been a horrible year plus. But the officers of the Society have been meeting on a regular basis trying hard to keep the Society going. Now it is your turn to come and get involved once again. After all, a Society is not a society if we don't gather! Make sure to mark your calendar for August 7th, put on your best Tartan and we will see you then. As Aye, Helen Jacobsen Gathering of the Clans :an occasion when a large group of family or friends meet, especially to enjoy themselves e.g., Highland Games. See page 5 for info about our Annual Meeting & Gathering of the Clans See page 15 for a listing of some nearby Gatherings Click here for Billy Raymond’s song “The Gathering of the Clans” To remove your name from our mailing list, The Scottish Society of Nebraska please reply with “UNSUBSCRIBE” in the subject line. -

The Provision of Lesbian Fiction in Public Libraries in Scotland Will Answer the Three Following Research Questions

THE PROVISION OF LESBIAN FICTION IN PULIC LIBRARIES IN SCOTLAND ALANNA BROADLEY This dissertation was submitted in part fulfilment of requirements for the degree of MSc Information and Library Studies DEPT. OF COMPUTER AND INFORMATION SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF STRATHCLYDE SEPTEMBER 2015 i DECLARATION This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MSc of the University of Strathclyde. I declare that this dissertation embodies the results of my own work and that it has been composed by myself. Following normal academic conventions, I have made due acknowledgement to the work of others. I declare that I have sought, and received, ethics approval via the Departmental Ethics Committee as appropriate to my research. I give permission to the University of Strathclyde, Department of Computer and Information Sciences, to provide copies of the dissertation, at cost, to those who may in the future request a copy of the dissertation for private study or research. I give permission to the University of Strathclyde, Department of Computer and Information Sciences, to place a copy of the dissertation in a publicly available archive. (please tick) Yes [ ] No [ ] I declare that the word count for this dissertation (excluding title page, declaration, abstract, acknowledgements, table of contents, list of illustrations, references and appendices is 21806 I confirm that I wish this to be assessed as a Type 1 2 3 4 5 Dissertation (please circle). Signature: Date: ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Ian Ruthven, for his guidance throughout the dissertation, and my parents, Laura and Calum, for their support. -

Ayrshire, Its History and Historic Families

BY THE SAME AUTHOR The Kings of Carrick. A Historical Romance of the Kennedys of Ayrshire ------- 5/- Historical Tales and Legends of Ayrshire - - 5/- The Lords of Cunningham. A Historical Romance of the Blood Feud of Eglinton and Glencairn - - 5/- Auld Ayr. A Study in Disappearing Men and Manners - - Net 3/6 The Dule Tree of Cassillis ... - Net 3/6 Historic Ayrshire. A Collection of Historical Works treating of the County of Ayr. Two Volumes - Net 20/- Old Ayrshire Days Net 4/6 AYRSHIRE Its History and Historic Families BY WILLIAM ROBERTSON VOLUME II Kilmarnock Dunlop & Drennan, "Standard" Office- Ayr Stephen & Pollock 1908 CONTENTS OF VOLUME II PAGE Introduction i I. The Kennedys of Cassillis and Culzean 3 II. The Montgomeries of Eglinton - - 43 III. The Boyles of Kelburn - - - 130 IV. The Dukedom of Portland - - - 188 V. The Marquisate of Bute - - - 207 VI. The Earldom of Loudoun ... 219 VII. The Dalrymples of Stair - - - 248 VIII. The Earldom of Glencairn - - - 289 IX. The Boyds of Kilmarnock - - - 329 X The Cochranes of Dundonald - - 368 XI. Hamilton, Lord Bargany - - - 395 XII. The Fergussons of Kilkerran - - 400 INTRODUCTION. The story of the Historic Families of Ayrshire is one of «xceptional interest, as well from the personal as from the county, as here and there from the national, standpoint. As one traces it along the centuries he realises, what it is sometimes difficult to do in a general historical survey, what sort of men they were who carried on the succession of events, and obtains many a glimpse into their own character that reveals their individuality and their idiosyncracies, as well as the motives that actuated and that animated them. -

England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales Inventory List Please Use This List to Check Off Items Before Returning the Kit to Milner Library

England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales Inventory List Please use this list to check off items before returning the kit to Milner Library. Box – Part 1 Audiotapes and CDs (in 1 bag) Crossroads of the Celts: Medieval Music of Ireland, Brittany, Scotland and Wales (cd) Dubliners: The Best of the Dubliners (tape) (original) Songs of Scotland (cd) Books Ancient Celts: Stencils Castles of the World Coloring Book Celtic Alphabet: Laser-Cut Plastic Stencils (3 in envelope inside book) Collins Gem Scots Dictionary The Cotswolds By Car – Book 2 (the Jarrold ‘White Horse’ Series) Cut & Assemble a Medieval Castle: A Full Color Model of Caernorvon Castle in Wales Elizabethan England (World History Series) Favorite Celtic Fairytales Favorite Irish Folk Tales Flower Fairies of the Spring Flower Fairies of the Trees The Garnet-Eyed Brooch (Early Feudal England) (One Unit in the Spindle Stories Women’s World History Series) Henry VIII and His Wives Paper Dolls Hero-Tales of Ireland The Irish Phrase-Book Medieval Britain Scottish Fairy and Folk Tales The Story of King Arthur and His Knights Teacher’s Manual (blue 3-ring binder) Yellow Pages: London South West 1996/97 (phone book) Young People in Britain Brochures and Guides British Elegance: Decorative Arts From Burghley House Family Fun Guide (blue binder) The Royal Line of Succession Magazines British Heritage (5 individual ‘binders’, entire issues) Calliope (4 individual ‘binders, entire issues, 3 articles total, 1 = duplicate) Cobblestone (1 binder, 1 article) Kids Discover (1 article) Faces, The Magazine About People (4 individual ‘binders’, entire issues) 1 | England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales Inventory List Magazines cont’d Ireland of the Welcomes (1 binder) National Geographic (7 individual binders, 8 articles total) National Geographic Traveler (2 individual binders, 3 articles total) Smithsonian (3 individual binders, 3 articles total) Packets Stonehenge (4 parts) (all in 1 bag) - 1. -

Polling Scheme

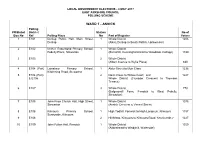

LOCAL GOVERNMENT ELECTIONS - 4 MAY 2017 EAST AYRSHIRE COUNCIL POLLING SCHEME WARD 1 - ANNICK Polling PO/Ballot District Station No of Box No Ref Polling Place No Part of Register Voters 1 E101 Dunlop Public Hall, Main Street, 1 Whole District 1286 Dunlop (Aiket, Dunlop to South Pollick, Uplawmoor) 2 E102 Nether Robertland Primary School, 1 Whole District Pokelly Place, Stewarton (Barnahill, Cunninghamhead to Woodside Cottage) 1199 3 E103 2 Whole District (Albert Avenue to Wylie Place) 830 4 E104 (Part) Lainshaw Primary School, 1 Alder Street to Muir Close 1236 Kilwinning Road, Stewarton 5 E104 (Part) 2 Nairn Close to Willow Court; and 1227 & E106 Whole District (Crusader Crescent to Thomson Terrace) 6 E107 3 Whole District 770 (Balgraymill Farm, Fenwick to West Pokelly, Stewarton) 7 E105 John Knox Church Hall, High Street, 1 Whole District 1075 Stewarton (Annick Crescent to Vennel Street) 8 E108 Kilmaurs Primary School, 1 High Todhill, Fenwick to High Langmuir, Kilmaurs 1157 Sunnyside, Kilmaurs 9 E108 2 Hill Moss, Kilmaurs to Kilmaurs Road, Knockentiber 1227 10 E109 John Fulton Hall, Fenwick 1 Whole District 1350 (Aitkenhead to Windyhill, Waterside) 2 WARD 2 - KILMARNOCK NORTH Polling PO/Ballot District Station No of Box No Ref Polling Place No Part of Register Voters 11 E201 (Part) St John’s Parish Church Main Hall, 1 Altonhill Farm to Newmilns Gardens 1046 Wardneuk Drive, Kilmarnock 12 E201 (Part) 2 North Craig, Kilmarnock to Grassmillside, Kilmaurs 1029 13 E202 3 Whole District 1094 (Ailsa Place to Toponthank Lane) 14 E203 (Part) Hillhead -

Clan Websites

Clan Websites [Clan Names in Red are new.] Clan Baird Society www.clanbairdsociety.com House of Boyd Society www.clanboyd.org Clan Buchanan Society International http://www.theclanbuchanan.com/ Clan Campbell Society (North America) https://www.ccsna.org/ Clan Davidson Society of North America https://clandavidson.org/ Clan Donald https://clandonaldusa.org/ Clan Donnachaidh http://www.donnachaidh.com/ Elliot Clan Society http://www.elliotclan.com/ Clan Farquharson https://clanfarquharson.org/ Clan Forrester Society http://clanforrester.org/ Clan Fraser Society of North America http://cfsna.com/ Clan Graham https://www.clangrahamsociety.org/ Clan Gregor Society http://acgsus.org/ Clan Gunn Society of North America www.clangunn.us Clan Hay http://www.clanhay.org/ Clan Henderson Society www.clanhendersonsociety.org St. Andrew's Society of Detroit Page 1 of 3 Posted: 22-Jul-2019 Charles S. Low Memorial Library Clan-Website-List-2019-07-22 Clan Websites Clan Irvine http://www.irvineclan.com Clan Kennedy http://www.kennedysociety.net/ http://www.kennedysociety.org/ Clan Kincaid http://www.clankincaid.org/Home Clan MacAlpine Society www.macaplineclan.com Clan MacCallum – Malcolm Society of North America, Inc. http://clan-maccallum-malcolm.org/ Clan MacFarlane https://www.macfarlane.org/ Clan MacInnes https://macinnes.org/ Clan MacIntosh http://www.mcintoshweb.com/clanMcIntosh/ Clan MacIntyre http://www.greatscottishclans.com/clans/macintyre.php Clan MacKay Society of the USA www.clanmackayusa.org Clan MacKinnon Society https://www.themackinnon.com/ Clan MacLachlan Association of North America http://www.cmana.net/ Clan MacLean Association in the United States https://maclean.us.org/ Clan MacLellan https://www.clanmaclellan.net/ Clan MacLeod of Harris https://www.clanmacleodusa.org/ Clan MacLeod of Lewis www.clanmacleodusa.org St.