Auld Lang Syne!’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

The Silver Tassie

The Silver Tassie MY BONIE MARY An old Jacobite ballad rewritten by the Bard. A silver tassie is a silver goblet and the Ferry which is mentioned in the poem is Queensferry, now the site of the two bridges which span the Forth, a short distance from Edinburgh. Go fetch to me a pint 0' wine, And fill it in a silver tassie; That I may drink before I go, A service to my bonie lassie: The boat rocks at the Pier 0' Leith, Fu' loud the wind blaws frae the Ferry, The ship rides by the Berwick-Law, And I maun leave my bonie Mary. maun = must The trumpets sound, the banners fly The glittering spears are ranked ready, The shouts 0' war are heard afar, The battle closes deep and bloody. It's not the roar 0' sea or shore, Wad mak me longer wish to tarry; Nor shouts 0' war that's heard afar- It's leaving thee, my bonie Mary! Afion Water This is a particularly lovely piece which is always a great favourite when sung at any Bums gathering. It refers to the River Afion, a small river, whose beauty obviously greatly enchanted the Bard. Flow gently, sweet Afcon, among thy green braes! braes = banks Flow gently, I'll sing thee a song in thy praise! My Mary's asleep by thy murmuring stream - Flow gently, sweet Afton, disturb not her dream! Thou stock-dove whose echo resounds thro' the glen, stuck dm =a wood pipn Ye wild whistling blackbirds in yon thorny den, yon = yonder Thou green-crested lapwing, thy screaming forbear, I charge you, disturb not my slumbering Fair! How lofey, sweet Afion, thy neighbouring hills, Far markd with the courses of clear, winding -

Download PDF 8.01 MB

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Imagining Scotland in Music: Place, Audience, and Attraction Paul F. Moulton Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC IMAGINING SCOTLAND IN MUSIC: PLACE, AUDIENCE, AND ATTRACTION By Paul F. Moulton A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Paul F. Moulton defended on 15 September, 2008. _____________________________ Douglass Seaton Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Eric C. Walker Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member _____________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Alison iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In working on this project I have greatly benefitted from the valuable criticisms, suggestions, and encouragement of my dissertation committee. Douglass Seaton has served as an amazing advisor, spending many hours thoroughly reading and editing in a way that has shown his genuine desire to improve my skills as a scholar and to improve the final document. Denise Von Glahn, Michael Bakan, and Eric Walker have also asked pointed questions and made comments that have helped shape my thoughts and writing. Less visible in this document has been the constant support of my wife Alison. She has patiently supported me in my work that has taken us across the country. She has also been my best motivator, encouraging me to finish this work in a timely manner, and has been my devoted editor, whose sound judgement I have come to rely on. -

An Afternoon at the Proms 24 March 2018

AN AFTERNOON AT THE PROMS 24 MARCH 2018 CONCERT PROGRAM MELBOURNE SIR ANDREW DAVIS TASMIN SYMPHONY LITTLE ORCHESTRA Courtesy B Ealovega Established in 1906, the Chief Conductor of the Tasmin Little has performed Melbourne Symphony Orchestra Melbourne Symphony Melbourne Symphony in prestigious venues Sir Andrew Davis conductor Orchestra (MSO) is an Orchestra, Sir Andrew such as Carnegie Hall, the arts leader and Australia’s Davis is also Music Director Concertgebouw, Barbican Tasmin Little violin longest-running professional and Principal Conductor of Centre and Suntory Hall. orchestra. Chief Conductor the Lyric Opera of Chicago. Her career encompasses Sir Andrew Davis has been He is Conductor Laureate performances, masterclasses, Elgar In London Town at the helm of MSO since of both the BBC Symphony workshops and community 2013. Engaging more than Orchestra and the Toronto outreach work. Vaughan Williams The Lark Ascending 3 million people each year, Symphony, where he has Already this year she has the MSO reaches a variety also been named interim Vaughan Williams English Folksong Suite appeared as soloist and of audiences through live Artistic Director until 2020. in recital around the UK. performances, recordings, Britten Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra In a career spanning more Recordings include Elgar’s TV and radio broadcasts than 40 years he has Violin Concerto with Sir Wood Fantasia on British Sea Songs and live streaming. conducted virtually all the Andrew Davis and the Royal Elgar Pomp and Circumstance March No.1 Sir Andrew Davis gave his world’s major orchestras National Scottish Orchestra inaugural concerts as the and opera companies, and (Critic’s Choice Award in MSO’s Chief Conductor in at the major festivals. -

Introduction to Scots Literacy

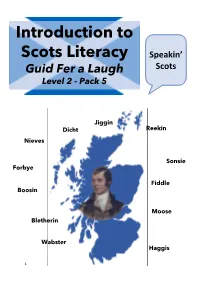

Introduction to Scots Literacy Speakin’ Scots Guid Fer a Laugh Level 2 - Pack 5 Jiggin Dicht Reekin Nieves Sonsie Forbye Fiddle Boosin Moose Bletherin Wabster Haggis 1 Introduction to Guid Fer A Laugh We are part of the City of Edinburgh Council, South West Adult Learning team and usually deliver ‘Guid Fer a Laugh’ sessions for community groups in South West Edinburgh. Unfortunately, we are unable to meet groups due to Covid-19. Good news though, we have adapted some of the material and we hope you will join in at home. Development of Packs We plan to develop packs from beginner level 1 to 5. Participants will gradually increase in confidence and by level 5, should be able to: read, recognise, understand and write in Scots. Distribution During Covid-19 During Covid-19 restrictions we are emailing packs to community forums, organisations, groups and individuals. Using the packs The packs can be done in pairs, small groups or individually. They are being used by: families, carers, support workers and individuals. The activities are suitable for all adults but particularly those who do not have access to computer and internet. Adapting Packs The packs can be adapted to suit participants needs. For example, the Pilmeny Development Project used The Scot Literacy Pack as part of a St Andrews Day Activity Pack which was posted out to 65 local older people. In the pack they included the Scot Literacy Pack 1 and 2, crosswords, short bread and a blue pen. Please see photo. 2 The Aims of the Session – Whit’s it a’aboot? • it’s about learning Scots language and auld words • takes a look at Scots comedy, songs, poetry and writing • hae a guid laugh at ourselves and others Feedback fae folk This is pack number five and we move on a little to Level 2. -

A Discography of Robert Burns 1948 to 2002 Thomas Keith

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 33 | Issue 1 Article 30 2004 A Discography of Robert Burns 1948 to 2002 Thomas Keith Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Keith, Thomas (2004) "A Discography of Robert Burns 1948 to 2002," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 33: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol33/iss1/30 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas Keith A Discography of Robert Bums 1948 to 2002 After Sir Walter Scott published his edition of border ballads he came to be chastised by the mother of James Hogg, one Margaret Laidlaw, who told him: "There was never ane 0 my sangs prentit till ye prentit them yoursel, and ye hae spoilt them awthegither. They were made for singing an no forreadin: butye hae broken the charm noo, and they'll never be sung mair.'l Mrs. Laidlaw was perhaps unaware that others had been printing Scottish songs from the oral tradition in great numbers for at least the previous hundred years in volumes such as Allan Ramsay's The Tea-Table Miscellany (1723-37), Orpheus Caledonius (1733) compiled by William Thompson, James Oswald's The Cale donian Pocket Companion (1743, 1759), Ancient and Modern Scottish Songs (1767, 1770) edited by David Herd, James Johnson's Scots Musical Museum (1787-1803) and A Select Collection of Original Scotish Airs (1793-1818) compiled by George Thompson-substantial contributions having been made to the latter two collections by Robert Burns. -

How Robert Burns Captured America James M

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 30 | Issue 1 Article 25 1998 How Robert Burns Captured America James M. Montgomery Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Montgomery, James M. (1998) "How Robert Burns Captured America," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 30: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol30/iss1/25 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. James M. Montgomery How Robert Burns Captured America Before America discovered Robert Bums, Robert Bums had discovered America. This self-described ploughman poet knew well the surge of freedom which dominated much of Europe and North America in the waning days of the eight eenth century. Bums understood the spirit and the politics of the fledgling United States. He studied the battles of both ideas and infantry. Check your knowledge of American history against Bums's. These few lines from his "Ballad on the American War" trace the Revolution from the Boston Tea Party, through the Colonists' invasion of Canada, the siege of Boston, the stalemated occupation of Philadelphia and New York, the battle of Saratoga, the southern campaign and Clinton's failure to support Cornwallis at Yorktown. Guilford, as in Guilford Court House, was the family name of Prime Minister Lord North. When Guilford good our Pilot stood, An' did our hellim thraw, man, Ae night, at tea, began a plea, Within America, man: Then up they gat to the maskin-pat, And in the sea did jaw, man; An' did nae less, in full Congress, Than quite refuse our law, man. -

ROBERT BURNS and FRIENDS Essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows Presented to G

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Robert Burns and Friends Robert Burns Collections 1-1-2012 ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy Patrick G. Scott University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Kenneth Simpson See next page for additional authors Publication Info 2012, pages 1-192. © The onC tributors, 2012 All rights reserved Printed and distributed by CreateSpace https://www.createspace.com/900002089 Editorial contact address: Patrick Scott, c/o Irvin Department of Rare Books & Special Collections, University of South Carolina Libraries, 1322 Greene Street, Columbia, SC 29208, U.S.A. ISBN 978-1-4392-7097-4 Scott, P., Simpson, K., eds. (2012). Robert Burns & Friends essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy. P. Scott & K. Simpson (Eds.). Columbia, SC: Scottish Literature Series, 2012. This Book - Full Text is brought to you by the Robert Burns Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Burns and Friends by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Author(s) Patrick G. Scott, Kenneth Simpson, Carol Mcguirk, Corey E. Andrews, R. D. S. Jack, Gerard Carruthers, Kirsteen McCue, Fred Freeman, Valentina Bold, David Robb, Douglas S. Mack, Edward J. Cowan, Marco Fazzini, Thomas Keith, and Justin Mellette This book - full text is available at Scholar Commons: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/burns_friends/1 ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy G. Ross Roy as Doctor of Letters, honoris causa June 17, 2009 “The rank is but the guinea’s stamp, The Man’s the gowd for a’ that._” ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. -

November 2020

‘The Vision’ The Robert Burns World Federation Newsletter Issue 47 November 2020 I have decided to give the newsletter the title of ‘The Vision’ as a nod to Burns’s poem of that name in which he bemoans the lack of recognition for poets from his native Ayrshire. His vision involves the appearance the muse Coila. However, the critic David Daiches remarked that ‘the poet does not quite know what to do with her when he brought her in.’ In composing this edition of the newsletter, I felt much the same as I didn’t know what I was going to do about the lack of copy which normally flows in unsolicited from around the world. Fortunately, my colleagues on the Board came up trumps and offered various leads for suitable material. It is a pleasure to report on a very successful Tamfest which explored Burns’s famous poem Tam o’ Shanter in great depth. The importance of music in relation to Burns also comes across strongly with a couple of articles highlighting his continuing influence on contemporary performers. Editor In this Issue: Page Halloween - Profile of President Marc Sherland 1-2 - A New Tartan for the Federation 2 Amang the bonie winding banks, - Lesley McDonald elected at President of LABC 2 Where Doon rins, wimpling, clear; - Tamfest 2020 3 - Simon Lamb Performance Poet 3 Where Bruce ance ruled the martial ranks, - Singer Lauren McQuistin 4-5 An’ shook his Carrick spear; - Heritage Item, Burns’s Mother’s Well 5 Some merry, friendly, country-folks - 200 Club 6 - New Burns Selection for Every Day 6 Together did convene, - St Andrew’s Day Lecture 6 To burns their nits, an’ pou their stocks, - Volunteers for Ellisland 7 An’ haud their Hallowe’en - Habbie Poetry Competition 8 - Federation Yule Concert 9 Fu’ blythe that night. -

Comprehension – Robert Burns – Y5m/Y6d – Brainbox Remembering Burns Robert Burns May Be Gone, but He Will Never Be Forgotten

Robert Burns Who is He? Robert Burns is one of Scotland’s most famous poets and song writers. He is widely regarded as the National Poet of Scotland. He was born in Ayrshire on the 25th January, 1759. Burns was from a large family; he had six other brothers and sisters. He was also known as Rabbie Burns or the Ploughman Poet. Childhood Burns was the son of a tenant farmer. As a child, Burns had to work incredibly long hours on the farm to help out. This meant that he didn’t spend much time at school. Even though his family were poor, his father made sure that Burns had a good education. As a young man, Burns enjoyed reading poetry and listening to music. He also enjoyed listening to his mother sing old Scottish songs to him. He soon discovered that he had a talent for writing and wrote his first song, Handsome Nell, at the age of fifteen. Handsome Nell was a love song, inspired by a farm servant named Nellie Kilpatrick. Becoming Famous In 1786, he planned to emigrate to Jamaica. His plans were changed when a collection of his songs and poems were published. The first edition of his poetry was known as the Kilmarnock edition. They were a huge hit and sold out within a month. Burns suddenly became very popular and famous. That same year, Burns moved to Edinburgh, the capital city of Scotland. He was made very welcome by the wealthy and powerful people who lived there. He enjoyed going to parties and living the life of a celebrity. -

"Auld Lang Syne" G

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Selected Essays on Robert Burns by G. Ross Roy Robert Burns Collections 3-1-2018 "Auld Lang Syne" G. Ross Roy University of South Carolina - Columbia Publication Info 2018, pages 77-83. (c) G. Ross Roy, 1984; Estate of G. Ross Roy; and Studies in Scottish Literature, 2019. First published as introduction to Auld Lang Syne, by Robert Burns, Scottish Poetry Reprints, 5 (Greenock: Black Pennell, 1984). This Chapter is brought to you by the Robert Burns Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Selected Essays on Robert Burns by G. Ross Roy by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “AULD LANG SYNE” (1984) A good case can be made that “Auld Lang Syne” is the best known “English” song in the world, & perhaps the best known in any language if we except national anthems. The song is certainly known throughout the English-speaking world, including countries which were formerly part of the British Empire. It is also known in most European countries, including Russia, as well as in China and Japan. Before and during the lifetime of Robert Burns the traditional Scottish song of parting was “Gude Night and Joy be wi’ You a’,” and there is evidence that despite “Auld Lang Syne” Burns continued to think of the older song as such. He wrote to James Johnson, for whom he was writing and collecting Scottish songs to be published in The Scots Musical Museum (6 vols. Edinburgh, 1787-1803) about “Gude Night” in 1795, “let this be your last song of all the Collection,” and this more than six years after he had written “Auld Lang Syne.” When Johnson published Burns’s song it enjoyed no special place in the Museum, but he followed the poet’s counsel with respect to “Gude Night,” placing it at the end of the sixth volume. -

The Prayer of Holy Willie

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications English Language and Literatures, Department of 7-7-2015 The rP ayer of Holy Willie: A canting, hypocritical, Kirk Elder Patrick G. Scott University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/engl_facpub Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Publication Info Published in 2015. Introduction and editorial matter copyright (c) Patrick Scott nda Scottish Poetry Reprint Series, 2015. This Book is brought to you by the English Language and Literatures, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PRAYER OF HOLY WILLIE by ROBERT BURNS Scottish Poetry Reprints Series An occasional series edited by G. Ross Roy, 1970-1996 1. The Life and Death of the Piper of Kilbarchan, by Robert Semphill, edited by G. Ross Roy (Edinburgh: Tragara Press, 1970). 2. Peblis, to the Play, edited by A. M. Kinghorn (London: Quarto Press, 1974). 3. Archibald Cameron’s Lament, edited by G. Ross Roy (London: Quarto Press, 1977). 4. Tam o’ Shanter, A Tale, by Robert Burns, ed. By G. Ross Roy from the Afton Manuscript (London: Quarto Press, 1979). 5. Auld Lang Syne, by Robert Burns, edited by G. Ross Roy, music transcriptions by Laurel E. Thompson and Jonathan D. Ensiminger (Greenock: Black Pennell Press, 1984). 6. The Origin of Species, by Lord Neaves, ed. Patrick Scott (London: Quarto Press, 1986). 7. Robert Burns, A Poem, by Iain Crichton Smith (Edinburgh: Morning Star, 1996).